Sedimentary blankets

Visual evidence for vast continental flooding

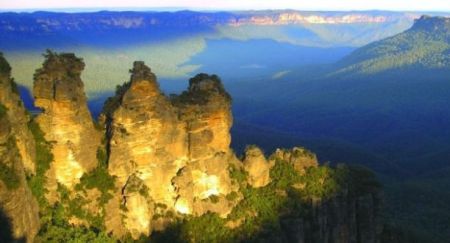

At Echo Point west of Sydney, Australia, visitors have a panoramic view of The Three Sisters—spectacular remains of a huge sandstone outcrop, broken and teetering on the edge of a wide valley. In the distance you can see the same sedimentary strata in vertical cliffs that stretch as far as the eye can see. These sedimentary layers also travel out of sight under the earth—much further than many suspect, 100 km (60 miles) east to the Pacific Ocean, 200 km north and 200 km south.1 They form part of the Sydney basin, a geological structure where layers of sediments accumulated to a depth of 3 km (figure 1).2

You can see the same geological pattern when you stand on the rim of Grand Canyon in western USA. As you peer across the abyss you marvel at the horizontal rock layers that decorate the walls—the same pattern on both sides of the canyon. Some layers form sheer cliffs; others crumble into sloped aprons. With so little vegetation in the area, the layers stand out and can be traced into the distant haze. In fact, these sedimentary formations have been recognized over thousands of kilometres across North America.3

British geologist Derek Ager in his book The Nature of the Stratigraphical Record4 marvelled at the way sedimentary rock layers persisted for thousands of kilometres across continents. Like a blanket, they are relatively thin compared with the area they cover.

He mentioned the chalk beds that form the famous White Cliffs of Dover in Southern England and explained that they are also found in Antrim in Northern Ireland, and can be traced into northern France, northern Germany, southern Scandinavia to Poland, Bulgaria and eventually to Turkey and Egypt. He described many other cases, yet even after that he said, “There are even more examples of very thin units that persist over fantastically large areas … ”

Another example that Ager could have mentioned is the Great Artesian Basin. This covers most of Eastern Australia (figure 2) and its individual strata run continuously for thousands of kilometres.5 Its sandstone members store enormous volumes of underground water, which allowed ranchers to graze livestock and settle the arid outback (figure 3).

One of the formations within this basin, often mentioned in the news when companies were drilling for oil and gas, is the so-called Hutton Sandstone. This rock formation, an easily-recognized target, was buried as much as 2 km in the middle of the basin but exposed at the surface at the edges—at places like Carnarvon Gorge in Queensland.

Layers of sediment blanketing such huge areas point to something unusual happening in the past. Today, blankets of sediments are not being deposited across the vast areas of the continents; if they were it would be difficult for humans to survive. Rather, sedimentation is localized, confined to the deltas of rivers and along the narrow strips of coastline.

A curious feature of these sedimentary blankets is that they contain evidence of rapid, energetic deposition. Geologists describe various strata as a “fluvial environment” or a “high energy braided stream system”,6 which is another way of saying the sediments were deposited by large volumes of fast flowing water that covered a very large area.

This evidence suggests a watery catastrophe that affected all the continents. It is reminiscent of the catastrophe described in the Bible—Noah’s Flood (Genesis 6-9). But people do not connect these sediments with Noah’s Flood, because the rocks are said to be hundreds of millions of years old. Are they? We need to realize that the ‘ages’ quoted were calculated by assuming that sedimentation was slow-and-gradual, which is why millions of years are needed. But a catastrophic inundation of the continents, as the evidence indicates, means the rocks were deposited quickly and didn’t take millions of years.

Next time you stand at a lookout and see geologic layers stretching across the landscape picture how these rocks also span entire continents. Remember that they are a visual reminder of the reality of the greatest catastrophe of all time, Noah’s Flood, which happened just 4,500 years ago—right before your eyes.

References

- Jones, D.C. and Clark, N.R., Geology of the Penrith 1:100,000 sheet 9030, NSW Geological Survey, Sydney, p.3, 1991. Return to text.

- Branagan, D.F and Packham, G.H., Field Geology of New South Wales, Department of Mineral Resources, Sydney, p.38, 2000. Return to text.

- Sloss, L.L.(ed.), The Geology of North America, Vol. D-2, Sedimentary Cover—North American Craton: U.S., The Geological Society of America, ch. 3, p. 47–51, 1988. Return to text.

- Ager, D., The Nature of the Stratigraphical Record, MacMillan, pp. 1–13, 1973. Return to text.

- Assessment of Groundwater Resources in the Broken Hill Region, Geoscience Australia, Professional Opinion 2008/05, ch. 6, 2008; www.environment.gov.au/water/publications/environmental/groundwater/broken-hill.html. Return to text.

- Day, R.W., et al., Queensland Geology: A Companion Volume, Geological Survey of Queensland, Brisbane, pp. 127–128, 1983. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.