Journal of Creation 14(1):81–90, April 2000

Browse our latest digital issue Subscribe

Ota Benga: the pygmy put on display in a zoo

One of the most fascinating historical accounts about the social effects of Darwinism is the story of Ota Benga, a pygmy who was put on display in an American zoo as an example of an evolutionarily inferior race. The incident clearly reveals the racism of Darwinism and the extent to which the theory gripped the hearts and minds of scientists and journalists in the early 1900s. As humans move away from this time in history, we can more objectively look back at the horrors that Darwinism has brought to society, of which this story is one poignant example.

Genetic differences are crucial to the theory of Darwinism because they are the only ultimate source of the innovation required for evolution. History and tradition has, often with tragic consequences, grouped human phenotypes that result from genotypic variations together into categories now called races. Races function as evolutionary selection units of such importance that the subtitle of Darwin’s classic 1859 book, The Origin of Species, was ‘The preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life.’ This work was critical in establishing the importance of the race fitness idea, and especially the ‘survival of the fittest’ concept. The question being asked in the early 1900s was:

‘Who was, [and] who wasn’t human? It was a big question in turn-of-the-century Europe and America … . The Europeans … were asking and answering it about Pygmies … often influenced by the current interpretations of Darwinism, so it was not simply who was human, but who was more human, and finally, who was the most human, that concerned them.’1

Darwinism spawned the belief that some races were physically closer to the lower primates and were also inferior. The polyphyletic view was that blacks evolved from the strong but less intelligent gorillas, the Orientals from the Orang-utans, and whites from the most intelligent of all primates, the chimpanzees.2 The belief that blacks were less evolved than whites, and (as many early evolutionists concluded) that they would eventually become extinct, is a major chapter in Darwinian history. The nefarious fruits of evolutionism, from the Nazis’ conception of racial superiority to its utilisation in developing their governmental policy, are all well documented.3,4

Some scientists felt that the solution to the problem of racism in early twentieth century America was to allow Darwinian natural selection to operate without interference. Bradford and Blume noted that Darwin taught that:

‘… when left to itself, natural selection would accomplish extinction. Without slavery to embrace and protect them, or so it was thought, blacks would have to compete with caucasians for survival. Whites’ greater fitness for this contest was [they believed] beyond dispute. The disappearance of blacks as a race, then, would only be a matter of time.’5

Each new American census showed that this prediction of Darwin was wrong because ‘the black population showed no signs of failing, and might even be on the rise.’ Not content ‘to wait for natural selection to grind out the answer,’ one senator even tried to establish programs to convince—or even force—Afro-Americans to return back to Africa.6

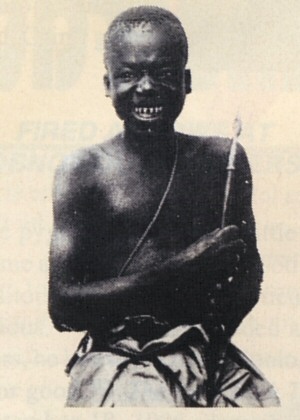

One of the more poignant incidents in the history of Darwinism and racism is the story of the man put on display in a zoo.7 Brought from the Belgian Congo in 1904 by noted African explorer Samuel Verner, he was eventually ‘presented by Verner to the Bronx Zoo director, William Hornaday’.8 The man, a pygmy named Ota Benga (or ‘Bi’ which means ‘friend’ in Benga’s language), was born in 1881 in central Africa. When placed in the zoo, although about twenty-three years old, he was only four feet eleven inches tall and weighed a mere 103 pounds. Often referred to as a boy, he was actually a twice-married father—his first wife and two children were murdered by the white colonists, and his second spouse died from a poisonous snake bite.9

Ota was first displayed as an ‘emblematic savage’ in the anthropology wing at the 1904 St Louis World’s Fair with other pygmies. The exhibit was under the direction of W.J. McGee of the St Louis World’s Fair Anthropology Department. McGee’s ambition for the exhibit was to ‘be exhaustively scientific’ in his demonstration of the stages of human evolution. Therefore he required ‘darkest blacks’ to set off against ‘dominant whites’ and members of the ‘lowest known culture’ to contrast with ‘its highest culmination’.10 Ironically, Professor Franz Boas of Columbia University ‘lent his name’ to the anthropological exhibit. This was ironic because Boas, a Jew who was one of the first anthropologists who opposed the racism of Darwinism, spent his life fighting the now infamous eugenics movement.11

The extremely popular exhibit attracted ‘considerable attention’.12 Pygmies were selected because they had attracted much attention as an example of a primitive race. One Scientific American article said:

‘The personal appearance, characteristics, and traits of the Congo pygmies … [they are] small, ape-like, elfish creatures, furtive and mischievous … [who] live in the dense tangled forests in absolute savagery, and while they exhibit many ape-like features in their bodies, they possess a certain alertness, which appears to make them more intelligent than other negroes … .The existence of the pygmies is of the rudest; they do not practice agriculture, and keep no domestic animals. They live by means of hunting and snaring, eking this out by means of thieving from the big negroes, on the outskirts of whose tribes they usually establish their little colonies, though they are as unstable as water, and range far and wide through the forests. They have seemingly become acquainted with metal only through contact with superior beings … .’13

During the pygmies’ stay in America, they were studied by scientists to learn how the ‘barbaric races’ compared with intellectually defective Caucasians on intelligence tests, and how they responded to such things as pain.14 The anthropometricists and psychometricists concluded that intelligence tests proved that pygmies were similar to ‘mentally deficient persons, making many stupid errors and taking an enormous amount of time’.15 Many Darwinists put the pygmies’ level of evolution ‘squarely in the Paleolithic period’ and Gatti concluded they had the ‘cruelty of the primitive man’.16 Nor did they do very well in sports. In Bradford and Blume’s words, ‘The disgraceful record set by the ignoble savages’ was so poor that ‘never before in the history of sport … were such poor performances recorded’.17

The anthropologists then measured not only the live humans, but in one case a ‘primitive’s’ head was ‘severed from the body and boiled down to the skull.’ Believing skull size was an ‘index of intelligence, scientists were amazed’ to discover the ‘primitive’s’ skull was ‘larger than that which had belonged to the statesman Daniel Webster’.18

A Scientific American editor concluded:

‘… of the native tribes to be seen in the exposition, the most primitive are the Negritos … nothing makes them so happy as to show their skill, by knocking a five-cent piece out of a twig of a tree at a distance of fifteen paces. Then there is the village of the Head-Hunting Igorotes, a race that is … a fine type of agricultural barbarians.’19

The same source referred to pygmies as ‘ape-like little black people’ and theorised that the evolution of the anthropoid apes was soon followed by:

‘… the earliest type of humanity which entered the Dark Continent, and these too, urged on by the pressure of superior tribes, were gradually forced into the great forests. The human type, in all probability, first emerged from the ape in south-eastern Asia, possibly in India. The higher types forced the negro from the continent in an eastward direction, across the intervening islands, as far as Australia, and westward into Africa. Even today, ape-like negroes are found in the gloomy forests, who are doubtless direct descendants of these early types of man, who probably closely resembled their simian ancestors … .

They are often dirty-yellowish brown in colour and covered with a fine down. Their faces are fairly hairy, with great prognathism, and retreating chins, while in general they are unintelligent and timid, having little tribal cohesion and usually living upon the fringes of higher tribes. Among the latter, individual types of the lower order crop out now and then, indicating that the two were, to a certain extent merged in past ages.’20

While on display, the pygmies were treated in marked contrast to how they first treated the whites who came to Africa to see them. When Verner visited the African king, ‘he was met with songs and presents, food and palm wine, drums. He was carried in a hammock.’ In contrast, when the Batwa were in St Louis they were treated:

‘With laughter. Stares. People came to take their picture and run away … [and] came to fight with them … . Verner had contracted to bring the Pygmies safely back to Africa. It was often a struggle just to keep them from being torn to pieces at the fair. Repeatedly … the crowds became agitated and ugly; the pushing and grabbing took on a frenzied quality. Each time, Ota and the Batwa were “extracted only with difficulty.”’21

Frequently, the police were summoned.

How Ota came to the United States

Ota Benga was spared from a massacre perpetuated by the Force Publique, a group of thugs working for the Belgium government endeavouring to extract tribute (in other words, steal labour and raw materials) from the native Africans in the Belgian Congo. After Ota successfully killed an elephant on a hunt, he returned to his people with the good news.

Tragically the camp Ota had left behind had ceased to exist—his wife and children were all murdered, and their bodies were mutilated in a campaign of terror undertaken by the Belgian government against the ‘evolutionarily inferior natives’.22 Ota was himself later captured, brought to a village, and sold into slavery.

In the meantime, Verner was looking for several pygmies to display at the Louisiana Purchase exposition and spotted Ota at a slave market. Verner bent down

‘… and pulled the pygmy’s lips apart to examine his teeth. He was elated; the filed [to sharp points] teeth proved the little man was one of those he was commissioned to bring back. … With salt and cloth he was buying him for freedom, Darwinism, and the West.’23

Ota’s world was shattered by the whites, and although he did not know if the white man who was now his master had the same intentions as the Belgians, he knew he had little choice but to go with Verner. Besides this, the events of the slave market were only one more event in Ota’s life which pushed him further into the nightmare which began with his discovery of the slaughter and gross mutilation of his family.

Verner managed to coerce only four pygmies to go back with him, a number which ‘fell far short of McGee’s initial specification,’ because ‘the shopping list … called for eighteen Africans, but it would do.’24

After the fair, Verner took Ota and the other pygmies back to Africa—Ota almost immediately remarried, but his second wife too soon died. He now no longer belonged to any clan or family since they were all killed or sold into slavery. The rest of his people also ostracised him, calling him a warlock, and claiming that he had chosen to stand in the white man’s world outside of theirs.

The white men were simultaneously admired and feared, and were regarded with both awe and concern: they could do things like record human voices on Edison cylinder phonographs which the pygmies saw as something that stole the ‘soul’ from the body, allowing the body to sit and listen to its soul talking.25

While back in Africa, Verner collected artefacts for his museums. He then decided to take Ota back to America (although Verner claims that it was Ota’s idea) for a visit—Verner would return him to Africa on his next trip.

Once back in America, Verner tried to sell his animals to zoos, and sell the crates of artefacts that he had brought back from Africa to museums. Verner was by then having serious money problems and could not afford to take care of Ota, so needed to place him somewhere. When Ota was presented to Director Hornaday of the Bronx Zoological Gardens, Hornaday’s intention was clearly to ‘display’ Ota. Hornaday ‘maintained the hierarchical view of races … large-brained animals were to him what Nordics were to Grant, the best evolution had to offer.’ 26 A ‘believer in the Darwinian theory’ he also concluded that there exists ‘a close analogy of the African savage to the apes.’27

At first Ota was free to wander around the zoo, helping out with the animals, but this was soon to drastically change.

‘Hornaday and other zoo officials had long been subject to a recurring dream in which a man like Ota Benga played a leading role … a trap was being prepared, made of Darwinism, Barnumism, pure and simple racism … so seamlessly did these elements come together that later those responsible could deny, with some plausibility, that there had ever been a trap or plan at all. There was no one to blame, they argued, unless it was a capricious pygmy or a self-serving press.’28

Ota was next encouraged to spend more time inside the monkey house. He was even given a bow and arrow and was encouraged to shoot it as part of ‘an exhibit’. Ota was soon locked in his enclosure—and when he was let out of the monkey house, ‘the crowd stayed glued to him, and a keeper stayed close by.’ 29 In the meantime, the publicity began—on September 9, a New York Times headline screamed ‘bushman shares a cage with Bronx Park apes.’ Although director Dr. Hornaday insisted that he was merely offering an ‘intriguing exhibit’ for the public’s edification, he:

‘… apparently saw no difference between a wild beast and the little black man; [and] for the first time in any American zoo, a human being was displayed in a cage. Benga was given cage-mates to keep him company in his captivity—a parrot and an orang-utan named Dohong.’8

A contemporary account stated that Ota was ‘not much taller than the orang-utan … their heads are much alike, and both grin in the same way when pleased.’ 30 Benga also came over from Africa with a ‘fine young chimpanzee’ which Mr Verner also deposited ‘in the ape collection at the Primates House’.31 Hornaday’s enthusiasm for his new primate exhibit was reflected in an article that he wrote for the zoological society’s bulletin, which begins as follows:

‘On September 9, a genuine African Pygmy, belonging to the sub-race commonly miscalled “the dwarfs,” … . Ota Benga is a well-developed little man, with a good head, bright eyes and a pleasing countenance. He is not hairy, and is not covered by the ‘downy fell’ described by some explorers … . He is happiest when at work, making something with his hands [emphasis in original].31

Hornaday then tells how he obtained the pygmy from Verner who

‘… was specially interested in the Pygmies, having recently returned to their homes on the Kasai River the half dozen men and women of that race who were brought to this country by him for exhibition in the Department of Anthropology at the St. Louis [World’s Fair] Exposition.’31

Bushman shares a cage with Bronx park apes

Some laugh over his antics, but many are not pleased

Keeper Frees Him at Times

Then, with bow and arrow, the Pygmy from the Congo takes to the woods

There was an exhibition at the Zoological Park, in the Bronx, yesterday which had for many of the visitors something more than a provocation to laughter. There were laughs enough in it too, but there was something about it which made the serious minded grave. Even those who laughed the most turned away with an expression on their faces such as one sees after a play with a sad ending or a book in which the hero or heroine is poorly rewarded.

‘Something about it that I don’t like,’ was the way one man put it. The exhibition was that of a human being in a monkey cage. The human being happened to be a Bushman, one of a race that scientists do not rate high in the human scale, but to the average nonscientific person in the crowd of sightseers there was something about the display that was unpleasant.

The human being caged was the little black man, Ota Benga, whom Prof. S. P. Verner, the explorer, recently brought to this country from the jungles of Central Africa. Prof. Verner lately handed him over to the New York Zoological Society for care and keeping. When he was permitted yesterday to get out of his cage, a keeper constantly kept his eyes on him. Benga appears to like his keeper too. It is probably a good thing that Benga doesn’t think very deeply. If he did it isn’t likely that he was very proud of himself when he woke in the morning and found himself under the same roof with the orangoutangs and monkeys, for that is where he really is.

The news that the pygmy would be on exhibition augmented the Saturday afternoon crowd at the Zoological Park yesterday, which becomes somewhat smaller as the Summer wanes. The monkey—or rather the primate-house is in the centre of Director Hornaday’s animal family.

The influence of evolution

The many factors motivating Verner to bring Ota to the United States were complex, but he was evidently ‘much influenced by the theories of Charles Darwin’, a theory which, as it developed, increasingly divided humankind up into arbitrarily contrived races.32 Darwin also believed that the blacks were an ‘inferior race’.33 As Hallet shows, Darwin also felt that the pygmies were inferior humans:

‘The Darwinian dogma of slow and gradual evolution from brutish ancestors … contributed to the pseudohistory of mankind. On the last page of his book The Descent of Man, Darwin expressed the opinion that he would rather be descended from a monkey than from a “savage.” He used the words savage, low and degraded to describe the American Indians, the Andaman Island Pygmies and the representatives of almost every ethnic group whose physical appearance and culture differed from his own. … [In this way] Charles Darwin libelled “the low and degraded inhabitants of the Andaman Islands” in his book The Descent of Man. The Iruri Forest Pygmies have been compared to “lower organisms”.’34

Although biological racism did not begin with Darwinism, Darwin did more than any other person to popularise it. As early as 1699, English physician Edward Tyson studied a skeleton which he believed belonged to a pygmy, concluding that this race were apes. It later turned out that the skeleton on which this conclusion was based was actually a chimpanzee.35

The conclusion accepted by most scientists in Verner’s day was that after Darwin ‘showed that all humans descended from apes’ he proved ‘that some races had descended farther than others … [and that] some races, namely the white ones, had left the ape far behind, while other races, pygmies especially, had hardly matured at all.’35 Many scientists agreed with scholar Sir Harry Johnson who studied the pygmies and concluded that they were ‘very apelike in appearance [and] their hairy skins, the length of their arms, the strength of their thickset frames, their furtive ways, their arboreal habits all point to these people as representing man in one of his earlier forms’.36

One of the most extensive early studies of the pygmies concluded that they were:

‘queer little freaks … . The low state of their mental development is shown by the following facts. They have no regard for time, nor have they any records or traditions of the past; no religion is known among them, nor have they any fetish rights; they do not seek to know the future by occult means … in short, they are … the closest link with the original Darwinian anthropoid ape extant.’ 37

The pygmies were in fact a talented group—experts at mimicry, physically agile, quick, nimble, and superior hunters, but the Darwinists did not look for these traits because they were blinded by their ‘evolution glasses’.38,39,40 Modern study has shown the pygmies in a far more accurate light and demonstrates how absurd the evolutionary worldview of the 1900s actually was.41

Ota Benga was referred to by Jayne as ‘a bright little man’42 who taught her how to make a set of ‘string figures’ that made up one chapter in her book on the subject. Construction of string figures is a lost folk art at which Ota excelled. Hallet, in defence of pygmies noted:

‘Darwin theorised that primitive people—or “savages”, as he called them—do not and cannot envision a universal and benevolent creator. Schebesta’s excellent study … correctly explains that the religion of the Ituri Forest Pygmies is founded on the belief that “God possesses the totality of vital force, of which he distributes a part to his creatures, an act by which he brings them into existence or perfects them.”Scientists still accept or endorse the theory of religious evolution propounded by Darwin and his nineteenth-century colleagues. They maintained that religion evolved from primitive animism to fetishism to polytheism to the heights of civilised Judeo-Christian monotheism. The Ituri Forest Pygmies are the most primitive living members of our species, yet far from being animistic, they pooh-pooh the local Negro tribes’ fears of evil spirits. “If darkness is, darkness is good,” according to a favourite Pygmy saying. “He who made the light also makes the darkness.” The Pygmies deplore as superstitious nonsense the Negroes’ magico-religious figurines and other so-called fetishes. They would take an equally dim view of churchly huts adorned with doll-like statues of Jesus and Mary. This would be regarded as idol worship by the Ituri Forest Pygmies, who believe that the divine power of the universe cannot be confined within material bounds. The authors of the Hebrew Old Testament would certainly agree, since they observed the well-known commandment forbidding “graven images” or idols.’43

Verner was no uninformed academic, but ‘compiled an academic record unprecedented at the University of South Carolina’, and in 1892 graduated first in his class at the age of 19 years. In his studies, Verner familiarised himself with the works of Charles Darwin. The Origin of Species and The Descent of Man engaged Verner on an intellectual level, as the theory of evolution promised to give scientific precision to racial questions that had long disturbed him. According to Darwin it was ‘more probable that our early progenitors lived on the African continent than elsewhere.’44

His studies motivated him to answer questions about Pygmies such as:

‘Are they men, or the highest apes? Who and what were their ancestors? What are their ethnic relations to the other races of men? Have they degenerated from larger men, or are the larger men a development of Pygmy forefathers? These questions arise naturally, and plunge the inquirer at once into the depths of the most heated scientific discussions of this generation.’45

One hypothesis that he considered was that:

‘Pygmies present a case of unmodified structure from the beginning [a view which is] … against both evolution and degeneracy. It is true that these little people have apparently preserved an unchanged physical entity for five thousand years. But that only carries the question back into the debated ground of the origin of species. The point at issue is distinct. Did the Pygmies come from a man who was a common ancestor to many races now as far removed from one another as my friend Teku of the Batwa village is from the late President McKinley?’46

Many people saw a clear conflict between evolution and Christianity, and ‘for most men, the moral resolve of an evangelist like Livingstone and the naturalism of a Darwin cancelled each other out.’ To Verner, though, no contradiction existed: he was ‘equally drawn to evangelism and evolutionism, Livingstone and Darwin’. In short, the ‘huge gap between religion and science’ did not concern Verner. He soon went to Africa to ‘satisfy his curiosity first hand about questions of natural history and human evolution … ’.47 He later wrote much about his trips to Africa, even advocating that whites take over Africa and run the country as ‘friendly directors’.48

Verner concluded that the Pygmies were the ‘most primitive race of mankind’ and were ‘almost as much at home in the trees as the monkeys.’49 He also argued that the blacks in Africa should be collected into reservations and colonised by ‘the white race’ and that the social and legal conflicts between races should be solved by ‘local segregation’.50,51Verner was not a mean person, and cared deeply for other ‘races,’ but this care was influenced in an extremely adverse way by his evolutionary beliefs.52

The Zoo Exhibit

Henry Fairfield Osborn—a staunch advocate of evolution who spent much of his life proselytising his evolutionary faith and attacking those who were critical of evolution, especially Williams Jennings Bryan, made the opening-day remarks when the zoo exhibit first opened. Osborn and other prominent zoo officials believed that not only was Ota less evolved, but that this exhibit allowed the Nordic race to have:

‘access to the wild in order to recharge itself. The great race, as he sometimes called it, needed a place to turn to now and then where, rifle in hand, it could hone its [primitive] instincts.’53

The Ota exhibit was described by contemporary accounts as a sensation—the crowds especially loved his gestures and faces.54 Some officials may have denied what they were trying to do, but the public knew full well the purpose of the new exhibit:

‘There was always a crowd before the cage, most of the time roaring with laughter, and from almost every corner of the garden could be heard the question ‘Where is the pygmy?” and the answer was, “in the monkey house”.’ 55

The implications of the exhibit were also clear from the visitors’ questions:

‘Was he a man or monkey? Was he something in between? “Ist dass ein Mensch?” asked a German spectator. “Is it a man?” … No one really mistook apes or parrots for human beings. This—it—came so much closer. Was it a man? Was it a monkey? Was it a forgotten stage of evolution?’ 56

One learned doctor even suggested that the exhibit should be used to help indoctrinate the public in the truth of evolution:

‘It is a pity that Dr. Hornaday does not introduce the system of short lectures or talks in connection with such exhibitions. This would emphasise the scientific character of the service, enhance immeasurably the usefulness of the Zoological Park to our public in general, and help our clergymen to familiarise themselves with the scientific point of view so absolutely foreign to many of them.’ 57

That he was on display was indisputable: a sign was posted on the enclosure which said:

‘The African Pygmy, “Ota Benga.” Age, 23 years. Height, 4 feet 11 inches. Weight 103 pounds. Bought from the Kasai River, Congo Free State, South Central Africa by Dr. Samuel P. Verner. Exhibited each afternoon during September.’ 55

And what an exhibit it was.

‘The orang-utan imitated the man. The man imitated the monkey. They hugged, let go, flopped into each other’s arms. Dohong [the orang-utan] snatched the woven straw off Ota’s head and placed it on his own. … the crowd hooted and applauded … children squealed with delight. To adults there was a more serious side to the display. Something about the boundary condition of being human was exemplified in that cage. Somewhere man shaded into non-human. Perhaps if they looked hard enough the moment of transition might be seen. … to a generation raised on talk of that absentee star of evolution, the Missing Link, the point of Dohong and Ota disporting in the monkey house was obvious.’58

The point of the exhibit was also obvious to a New York Times reporter who stated:

‘The pygmy was not much taller than the orang-utan, and one had a good opportunity to study their points of resemblance. Their heads are much alike, and both grin in the same way when pleased.’55

That he was made much fun of is also indisputable: he was once given a pair of shoes, concerning which ‘over and over again the crowd laughed at him as he sat in mute admiration of them.’55 In another New York Times article one of the editors, after studying the situation, penned the following:

‘Ota Benga … is a normal specimen of his race or tribe, with a brain as much developed as are those of its other members. Whether they are held to be illustrations of arrested development, and really closer to the anthropoid apes than the other African savages, or whether they are viewed as the degenerate descendants of ordinary negroes, they are of equal interest to the student of ethnology, and can be studied with profit … .As for Benga himself, he is probably enjoying himself as well as he could anywhere in this country, and it is absurd to make moan over the imagined humiliation and degradation he is suffering. The pygmies are a fairly efficient people in their native forests … but they are very low in the human scale, and the suggestion that Benga should be in a school instead of a cage ignores the high probability that school would be a place of torture to him and one from which he could draw no advantage whatever. The idea that men are all much alike except as they have had or lacked opportunities for getting an education out of books is now far out of date. With training carefully adapted to his mental limitations, this pygmy could doubtless be taught many things … but there is no chance that he could learn anything in an ordinary school.’59

That the display was extremely successful was never in doubt. Bradford and Blume claimed that on September 16, ‘40,000 visitors roamed the New York Zoological Park … the sudden surge of interest … was entirely attributable to Ota Benga.’ The crowds were so enormous that a police officer was assigned to guard Ota full-time (the zoo claimed this was to protect him) because he was ‘always in danger of being grabbed, yanked, poked, and pulled to pieces by the mob.’ 60

Although it was widely believed at this time, even by eminent scientists, that blacks were evolutionarily inferior to Caucasians, caging one in a zoo produced much publicity and controversy, especially from ministers and Afro-Americans:

‘… the spectacle of a black man in a cage gave a Times reporter the springboard for a story that worked up a storm of protest among Negro ministers in the city. Their indignation was made known to Mayor George B. McClellan, but he refused to take action.’61

When the storm of protests rose, Hornaday ‘saw no reason to apologise’ stating that he ‘had the full support of the Zoological Society in what he was doing.’62 Evidently not many persons were very concerned about doing anything until the Afro-American community entered the foray. Although even some blacks at this time accepted the notion that the pygmies were ‘defective specimens of mankind’ several black ministers were determined to stop the exhibit.55

The use of the display to argue that blacks were an inferior race made them especially angry. Their concern was ‘they had heard blacks compared with apes often enough before; now the comparison was being played flagrantly at the largest zoo on earth.’ In Reverend Gordon’s words, ‘our race … is depressed enough without exhibiting one of us with the apes. We think we are worthy of being considered human beings, with souls.’27 Further, many of the ministers opposed the theory of evolution, concluding that

‘… the exhibition evidently aims to be a demonstration of the Darwinian theory of evolution. The Darwinian theory is absolutely opposed to Christianity, and a public demonstration in its favour should not be permitted.’63

One Times article responded to the criticism that the display lent credibility to Darwinism with the following words:

‘One reverend coloured brother objects to the curious exhibition on the grounds that it is an impious effort to lend credibility to Darwin’s dreadful theories … the reverend coloured brother should be told that evolution … is now taught in the textbooks of all the schools, and that it is no more debatable than the multiplication table.’64

Yet, Publishers Weekly commented that the creationist ministers were the only ones that ‘truly cared’ about Ota.65

Soon some whites also became concerned about the ‘caged Negro’, and in Sifakis’ words, part of the concern was because ‘men of the cloth feared … that the Benga exhibition might be used to prove the Darwinian theory of evolution.’8 The objections were often vague, as in the words of a September 9 New York Times article:

‘The exhibition was that of a human being in a monkey cage. The human being happened to be a Bushman, one of a race that scientists do not rate high in the human scale, but to the average non-scientific person in the crowd of sightseers there was something about the display that was unpleasant. … It is probably a good thing that Benga doesn’t think very deeply. If he did it isn’t likely that he was very proud of himself when he woke in the morning and found himself under the same roof with the orang-utans and monkeys, for that is where he really is.’66

Man and Monkey Show disapproved by Clergy

The Rev. Dr. Macarthur thinks the exhibition degrading

Colored Ministers To Act

The Pygmy has an orang-outang as a companion now and their antics delight the Bronx

crowds

Several thousand persons took the Subway, the elevated, and the surface cars to the New York Zoological Park, in the Bronx, yesterday, and there watched Ota Benga, the Bushman, who has been put by the management on exhibition there in the monkey cage. The Bushman didn’t seem to mind it, and the sight plainly pleased the crowd. Few expressed audible objection to the sight of a human being in a cage with monkeys as companions, and there could be no doubt that to the majority the joint manandmonkey exhibition was the most interesting sight in Bronx Park.

All the same, a storm over the exhibition was preparing last night. News of what the managers of the Zoological Park were permitting reached the Rev. Dr. R.S. MacArthur of Calvary Baptist Church last night, and he announced his intention of communicating with the negro clergymen in the city and starting an agitation to have the show stopped.

‘The person responsible for this exhibition degrades himself as much as he does the African,’ said Dr. MacArthur. ‘Instead of making a beast of this little fellow, he should be put in school for the development of such powers as God gave to him. It is too bad that there is not some society like that for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. We send our missionaries to Africa to Christianize the people, and then we bring one here to brutalize him.

‘Our Christian missionary societies must take this matter up at once. I shall communicate with Dr. Gilbert of the Mount Olivet Baptist Church and other pastors of colored congregations, that we may work together in this matter. They will have my active assistance.’

Some reporters, instead of ridiculing the zoo, criticised those who objected to the exhibit because they did not accept evolution. In Bradford and Blume’s words, ‘New York scientists and preachers’ wrangled over Ota, and those who believed that ‘humans were not descended from the apes and that Darwinism was an anti-Christian fraud … were subject to ridicule on the editorial pages of the New York Times.’67 Although opinions about the incident varied, they did result in many formal protests and threats of legal action to which the zoo director eventually acquiesced, and ‘finally … allowed the pygmy out of his cage.’8 Once freed, Benga spent most of his time walking around the zoo grounds in a white suit, often with huge crowds following him. He returned to the monkey house only to sleep at night. Being treated as a curiosity, mocked, and made fun of by the visitors eventually caused Benga to ‘hate being mobbed by curious tourists and mean children’.68 In a letter to Verner, Hornaday revealed some of the many problems that the situation had caused:

‘Of course we have not exhibited him [Benga] in the cage since the trouble began. Since dictating the above … Ota Benga … procured a carving knife from the feeding room of the Monkey House, and went around the Park flourishing it in a most alarming manner, and for a long time refused to give it up. Eventually it was taken away from him. Shortly after that he went to the soda fountain near the Bird House, to get some soda, and because he was refused the soda he got into a great rage … This led to a great fracas. He fought like a tiger, and it took three men to get him back to the monkey house. He has struck a number of visitors, and has “raised Cain” generally.’69

He later ‘fashioned a little bow and a set of arrows and began shooting at zoo visitors he found particularly obnoxious’! The New York Times described the problem as follows:

‘There were 40,000 visitors to the park on Sunday. Nearly every man, woman and child of this crowd made for the monkey house to see the star attraction in the park—the wild man from Africa. They chased him about the grounds all day, howling, jeering, and yelling. Some of them poked him in the ribs, others tripped him up, all laughed at him.’70

‘After he wounded a few gawkers, he had to leave the Zoological Park for good.’ 71

The resolution of the controversy, in Ward’s words, came about because: ‘In the end Hornaday decided his prize exhibit had become more trouble than he was worth and turned him over to the Reverend Gordon, who also headed the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum in Brooklyn.’72

Hornaday claimed that he was ‘merely offering an interesting exhibit and that Benga was happy … ’. However Milner70 notes that this ‘statement could not be confirmed’ since we have no record of Benga’s feelings, but many of his actions reveal that he had adjusted poorly to zoo life. Unfortunately, Ota Benga did not leave any written records of his thoughts about this or anything else, thus the only side of the story that we have is Verner’s voluminous records, the writings by Hornaday, the many newspaper accounts, and a 281 page book entitled The Pygmy in the Zoo by Philip Verner Bradford, Verner’s grandson.

Bradford, in doing his research, had the good fortune that Verner saved virtually every letter that he had ever received, many of which discuss the Ota Benga situation, and all of which he had access to when doing his research. Interestingly, Verner related what he feels is the pygmy view of evolution:

‘After my acquaintance with the Pygmies had ripened into complete mutual confidence, I once made bold to tell them that some of the wise men of my country asserted that they had descended from the apes of the forest. This statement, far from provoking mirth, met with a storm of indignant protestation, and furnished the theme for many a heated discussion around the Batwa firesides.’73

After Benga left the zoo, he was able to find care at a succession of institutions and with several sympathetic individuals, but he was never able to shed his freak label and history. First sent to a ‘coloured’ orphanage, Ota learned English and also took an interest in a certain young lady there, a woman named Creola. Unfortunately even Ota’s supporters believed some of the stories about him, and an ‘incident’ soon took place which ignited a controversy. As a result, Ota was soon forever shuffled miles away from both Brooklyn and Creola.

In January 1910 he arrived at a black community in Lynchburg, VA, and there he seemed to shine.

‘… black families [there] entrusted their young to Ota’s care. They felt their boys were secure with him. He taught them to hunt, fish, gather wild honey. … The children felt safe when they were in the woods with him. If anything, they found him over-protective, except in regard to gathering wild honey—there was no such thing as too much protection when it came to raiding hives. … A bee sting can feel catastrophic to a child, but Ota couldn’t help himself, he thought bee stings were hilarious.’74

He became a baptized Christian and his English vocabulary rapidly improved. He also learned how to read—and occasionally attended classes at a Lynchburg seminary. He was popular among the boys, and learned several sports such as baseball (at which he did quite well). Every effort was made to help him blend in (even his teeth were capped to help him look more normal), and although he seemingly had adjusted, inwardly he had not.

Several events and changes that occurred there caused him to become despondent: after checking on the price of steamship tickets to Africa, he concluded that he would never have enough money to purchase one. He had not heard from Verner in a while, and did not know how to contact him. He later ceased attending classes and became a ten dollars a month plus room and board labourer on the Obery farm.75 The school concluded that his lack of education progress was because of his African ‘attitude’ but actually probably ‘his age was against his development. It was simply impossible to put him in a class to receive instructions … that would be of any advantage to him.’72 He had enormous curiosity and a drive to learn, but preferred performance tests as opposed to the multiple choice kind.

Later employed as a tobacco factory labourer in Lynchburg, he grew increasingly depressed, hostile, irrational, and forlorn. When people spoke to him, they noticed that he had tears in his eyes when he told them he wanted to go home. Concluding that he would never be able to return to his native land, on March 20, 1916 Benga committed suicide with a revolver.76 In Ward’s words:

‘Ota … removed the caps from his teeth. When his small companions asked him to lead them into the woods again, he turned them away. Once they were safely out of sight, he shot himself … .’72

To the end, Hornaday was inhumane, seriously distorting the situation, even slanderously stating that Ota ‘would rather die than work for a living’.77 In an account of his suicide published by Hornaday in the 1916 Zoological Bulletin, his evolution-inspired racist feelings clearly showed through:

‘… the young negro was brought to Lynchburg about six years ago, by some kindly disposed person, and was placed in the Virginia Theological Seminary and College here, where for several years he laboured to demonstrate to his benefactors that he did not possess the power of learning; and some two or three years ago he quit the school and went to work as a labourer [emphasis added].’78

In Hornaday’s words, Ota committed suicide because ‘the burden became so heavy that the young negro secured a revolver belonging to the woman with whom he lived, went to the cow stable and there sent a bullet through his heart, ending his life.’78

How does Verner’s grandson, a Darwinist himself, feel about the story? In his words, ‘The forest dwellers of Africa still arouse the interest of science. Biologists seek them out to test their blood and to bring samples of their DNA. They are drawn by new forms of the same questions that once vexed S.P. Verner and Chief McGee; What role do Pygmies play in human evolution? What relationship do they have to the original human type … ?’ He adds that one clear difference does exist, and that is, ‘Today’s evolutionists do not, like yesterday’s anthropometricists, include demeaning comments and rough treatments in their studies.’ They now openly admit that the ‘triumph of Darwinism’ was ‘soon after its inception [used] to reinforce every possible division by race, gender, and nationality’. Part of the problem also was that ‘the press, like the public, was fascinated by, or addicted to, the spectacle of primitive man’.79 The tragedy, as Buhler expressed in a poem, is:

‘From his native land of darkness, to the country of the free, in the interest of science … brought wee little Ota Benga … scarcely more than ape or monkey, yet a man the while … . Teach the freedom we have here in this land of foremost progress—in this Wisdom’s ripest age—we have placed him, in high honor, in a monkey’s cage! Mid companions we provide him, apes, gorillas, chimpanzees.’80,81

References

- Bradford, P.V. and Blume, H., Ota Benga; The Pygmy in the Zoo, St Martins Press, New York, p. 304, 1992. Return to text.

- Crookshank, T.G., The Mongol in Our Midst, E. F. Dutton, New York, 1924. Return to text.

- Bergman, J., Eugenics and the development of the Nazi race policy, Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith 44(2):109–123, 1992. Return to text.

- Bergman, J., Censorship in secular science; The Mims case, Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith 45(1):37–45, 1993. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, p. 40. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, p. 41. Return to text.

- Birx, H.J., Ota Benga: The pygmy in the zoo, Library Journal 117(13):134, 1992. Return to text.

- Sifakis, C., Benga, Ota: the zoo man, American Eccentrics, Facts on File Inc., New York, pp.252–253, 1984. Return to text.

- Bridges, W., Gathering of Animals; An Unconventional History of the New York Zoological Society, Harper and Row, New York, 1974. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, pp. 94–95. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, p. 113. Return to text.

- Verner, S.P., The African pygmies, Popular Science 69:471–473, 1906. Return to text.

- Munn and Company (ed.), The Government Philippines Expedition, Scientific American July 23, pp. 107–108, 1904. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, pp. 113–114. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, p. 121. Return to text.

- Gatti, A., Great Mother Forest, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1937. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, p. 122. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, p. 16. Return to text.

- Munn and Company, Ref. 13, p. 64. Return to text.

- Munn and Company (ed.), Pygmies of the Congo, Scientific American 93:107–108, August 5, 1905. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, pp. 118–119. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, p. 104. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, p. 106. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, p. 110. Return to text.

- Verner, S.P., The white man’s zone in Africa, World’s Work 13:8227–8236, 1906. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, p. 176. Return to text.

- Negro Ministers act to free pygmy; will ask the mayor to have him taken from the monkey cage. Committee visits the zoo; public exhibitions of the dwarf discontinued, but will be resumed, Mr Hornaday says, New York Times, p.2, September 11, 1906. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, p. 174. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, p. 180. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, p. 181. Return to text.

- Hornaday, W.T., An African pygmy, Zoological Society Bulletin 23:302, 1906. Return to text.

- Rymer, R., Darwinism, Barnumism and racism, Ota Benga: the pygmy in the zoo, The New York Times Book Review, p.3, September 6, 1992. Return to text.

- Verner, S.P., The white races in the tropics, World’s Work 16:10717, 1908. Return to text.

- Hallet, J-P, Pygmy Kitabu, Random House, New York, pp. 292, 358–359, 1973. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, p. 20. Return to text.

- Keane, A.H. J., Anthropological curiosities; the pygmies of the world, Scientific American 64(1650):99, July 6, 1907. Return to text.

- Burrows, G., The Land of the Pygmies, Thomas Y. Crowell & Co., New York, pp.172, 182, 1905. Return to text.

- Johnston, H.H., Pygmies of the great Congo forest, Smithsonian Report, pp. 479–491, 1902. Return to text.

- Johnston, H.H., Pygmies of the great Congo forest, Current Literature 32:294–295, 1902. Return to text

- Lloyd, A.B., Through dwarf land and cannibal country, Athenaeum 2:894–895, 1899. Return to text

- Turnbull, C., The Forest People, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1968. Return to text.

- Jayne, C.F., String Figures and How to Make Them, Dover Publishers, New York, p. 276, 1962, reprinted from the original publication; in: Jayne, C.F., String Figures, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1906. Return to text.

- Hallet, Ref. 34, pp. 14–15. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, pp. 69–70. Return to text.

- Verner, S.P., The African pygmies, Atlantic 90:192, 1902. Return to text.

- Verner, Ref. 45, p.193. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, p. 70, 72, 74. Return to text.

- Verner, Ref. 33, p. 10718. Return to text.

- Verner, Ref. 12, pp. 189–190. Return to text.

- Verner, Ref. 25, p. 8235. Return to text.

- Verner, S.P., Africa fifty years hence, World’s Work 13:8736, 1097. Return to text.

- Verner, S.P., An education experiment with cannibals, World’s Work 4:2289–2295, 1902. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, p. 175. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, p. 180. Return to text.

- Man and the monkey show disapproved by clergy; the Rev. Dr MacArthur thinks the exhibition degrading; colored ministers to act; The pygny has an orangutan as a companion and their antic delight the Bronx crowds, New York Times, p. 1, September 10, 1906. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, p. 179. Return to text.

- Gabriel, M. S., Ota Benga having a fine time; A visitor at the Zoo finds no reason for protests about the pygm’, New York Times, p. 6, September 13, 1906. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, p. 181. Return to text.

- Topic of the times; send him back to the woods, New York Times, p. 6, September 11, 1906. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, p. 185, 187. Return to text.

- Bridges, Ref. 9, p. 224. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, p. 182. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, p.183. Return to text.

- Topics of the times; The pigmy is not the point, New York Times, p. 8, September 12, 1906. Return to text.

- Ota Benga: the Pygmy in the Zoo, review in Publishers Weekly 239(23):56, 1992. Return to text.

- ‘Bushman shares a cage with Bronx Park apes; some laugh over his antics, but many are not pleased; keeper frees him at times; then, with bow and arrow, the pygmy from the Congo takes to the woods, New York Times, p. 9, September 9, 1906. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, pp. 191, 196. Return to text.

- Milner, R, The Encyclopedia of Evolution: Humanity’s Search For Its Origins, Facts on file Inc., New York, p, 42, 1990. Return to text.

- Bridges, Ref. 9, pp.227–228. Return to text.

- African pygmy’s fate is still undecided; Director Hornaday of the Bronx park throws up his hands; Asylum doesn’t take him; Benga meanwhile laughs and plays with a ball and mouth organ at the same time, New York Times, p.9, September 18, 1906. Return to text.

- Milner, Ref. 68. Return to text.

- Ward, G.C., Ota Benga: The pygmy in the zoo, American Heritage 43:12–14, 1992. Return to text.

- Verner, Ref. 45, p. 190. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, pp.206–207. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, p. 204. Return to text.

- Sanborn, E.R. (ed.), Suicide of Ota Benga, the African pygmy, Zoological Society Bulletin 19(3):1356, 1916. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, p. 220. Return to text.

- Hornaday, W.T., Suicide of Ota Benga, the African pygmy, Zoological Society Bulletin, 19(3):1356, 1916. Return to text.

- Bradford et al., Ref. 1, pp. xx, 7, 23–231. Return to text.

- Buhler, M.E., Ota Benga, New York Times, p. 8, September 19, 1906. Return to text.

- Note: The spelling in some of the quotes has been modernised. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.