Missing the mark

How a missionary family gave rise to the top name in ‘apeman’ research (Louis Leakey)!

Most people have heard of anthropologist Louis Leakey, best known as the man who changed the way that evolutionists think about the place where mankind supposedly evolved. He did this by finding ape-like fossils in East Africa and declaring them to be older than those that had been found in Asia, such as Eugene Dubois’ Java Man in Indonesia and Davidson Black’s Peking Man in China. However, most readers may not know of his once-strong Christian background.

Louis was born in 1903 at Kabete Mission Station, near Nairobi, British East Africa, now Kenya, where his English parents were missionaries with the Church Missionary Society. He grew up ‘more African than English’. As a child, he was fluent in the Kikuyu language as well as in English. He played African children’s games, built his own three-roomed mud-and-wattle hut, and learned to track animals and hunt with spear and club. Later he would claim that this training in observation and patience was the key to his proficiency in finding fossils. He was initiated into the Kikuyu Tribe as a junior warrior at age 11. The elders gave him the name Wakuruigi, meaning Son of the Sparrow Hawk, and from then on treated him, as with the other initiates, like an adult.

At age 13, he made a collection of obsidian (a type of rock1) flakes, and learned that they included some actual stone axe-heads and arrow-heads. His biographer says: ‘From that moment Louis became addicted to prehistory.’2

He attended Cambridge University from 1922 and graduated in archaeology and anthropology in 1926. He received a Ph.D. in 1930, and later various honorary doctorates. He now abandoned his youthful ambition to follow in his father’s footsteps as a missionary in East Africa, and from then on devoted his life to attempting to prove Darwin’s assertion that human evolution began in Africa, not Asia.3

Like father, like son

In 1933, in England, Louis met a 20-year-old scientific illustrator named Mary Nicol and asked her to help with drawings for his first book.4 Their association developed into an affair, even though he already had one young child, and his wife of five years was pregnant with another. She divorced him in 1936,5 and he and Mary were married that same year.

Louis and Mary, who has also made a name for herself in the field of human evolution, produced three children. Second son Richard, born in Kenya in 1944, is the best known, as he, too, became a paleontologist and proposed controversial interpretations of his fossil finds. Richard married in 1966, and then, in 1969, as his father had done 36 years previously, began an affair with a young scientist, when his wife had just given birth to their first child.6 The couple divorced, and a year later Richard married Meave Epps (who was an expert on fossilized monkeys). Their daughter, Louise, also became a paleontologist. This three-generation dynasty has been called by evolutionists ‘the first family of paleontology’.

In later years, Richard joined the list of individuals (such as vociferous evolutionary propagandist and zoologist Richard Dawkins) who endorsed the Humanist Manifesto 2000. In 1984, he had shown his loathing of creationists when he illogically refused to send any of Kenya’s original hominid fossils to a huge symposium held that year at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, saying that ‘such an exhibit was too risky in a country where creationists were active’.7 At the same symposium, Mary blasted the museum staff for ‘endangering irreplaceable fossils by … exhibiting them in a single room where a [religious] fundamentalist could come in with a bomb and destroy the whole legacy’!7

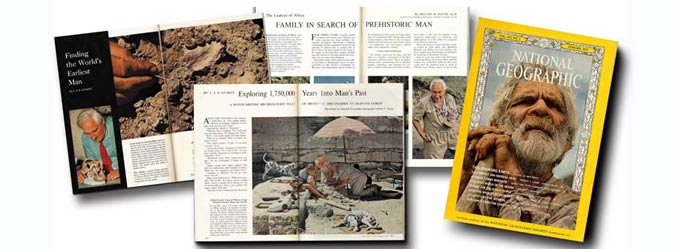

In 1959, Mary had found a robust skull with huge teeth in deposits that also contained stone tools. Louis claimed it was a human ancestor and named it Zinjanthropus (meaning East Africa Man) boisei.8 Because of the size of the teeth (the same size as that of the much bigger gorilla) and the large sagittal crest for the attachment of powerful jaw muscles, it was nicknamed Nutcracker Man. Most other anthropologists thought it was very un-human; however, National Geographic magazine printed the first of many articles about the Leakeys’ finds9 and sponsored them from then on.

Student capers

At Cambridge University from 1922 to 1926, Louis caused quite a stir. He talked the authorities into allowing him to take Kikuyu as one of his two modern-language requirements by producing a testimonial to his proficiency in it signed with the thumb-print of Kikuyu Chief Koinange.1 Then, in lieu of attending lectures in Kikuyu, of which there were none, he had to coach the university supervisor allotted to him! This gave rise to the legend that he was ‘the man who examined himself in Kikuyu’. Before going to Cambridge, Louis had offered his services to the London School of Oriental Studies to teach Kikuyu in their African Languages section. When Cambridge University asked the same London organization for two examiners in Kikuyu, they sent Leakey’s name, not realizing that he was also the student being examined. The impasse was solved when the supervisor assured the university that he could learn enough Kikuyu from Louis to be able to examine him in it!2

On another occasion Louis accepted a dare to say grace before dinner in Kikuyu instead of the customary Latin. He ‘droned sonorously through it without one of the dons [teachers] noticing’.1

References

- Morell, V., Ancestral Passions, Simon & Schuster, New York, p. 28, 1995.

- Leakey, L.S.B., White African, Hodder and Stoughton, London, pp. 95, 156–57, 1937.

Louis later conceded that Zinjanthropus was not a direct ancestor of modern man. But he claimed this distinction for other fossils his team discovered in Olduvai Gorge in 1960–63, naming them Homo habilis (or handy man). He said they were of a more advanced hominid, one which was definitely on the evolutionary line to Homo sapiens (modern man). Homo habilis has since been declared by most evolutionary paleontologists to be an ‘invalid taxon’ (biological category), i.e. a phantom species composed of a ‘waste-bin’ of fossils more correctly assigned to other species.10

Christian influences

As a young man, Louis had planned to make his life’s work that of a missionary.11 In Africa, he had seen the powerfully positive effect of Christianity in an animistic society. In his autobiography, he tells of two Kikuyu young people, Naomi and Ishmael, who were both Christians and who wanted to marry. However, their grandfathers had been enemies and, on his death-bed, Naomi’s grandfather ‘had uttered a curse to the effect that he would come from the spirit world and give serious trouble to all his family if they ever allowed any of his descendants to marry into his enemy’s family.’ Naomi and Ishmael went ahead and married anyway, and lived happily for many years. Louis commented that ‘the local non-Christian natives … have decided that Christians can ignore such curses with impunity, not only to themselves but also to their relations’.12

He also describes the Kikuyu taboo against touching a dead body, which meant that sick people about to die used to be carried out into the bush to expire there, where the corpses would be devoured by hyenas and so not need burying. He commented: ‘Naturally those Kikuyu who have become Christians have abandoned these old ideas and customs, and they are not in the least afraid of touching a human corpse or a human skull or skeleton … Christian Kikuyus are thus constantly in demand as undertakers.’13

As a young man Louis had been very zealous about Christianity. At Boscombe (near Bournemouth), he used to stand on a soap box and preach to passers-by on the streets. During his time at Cambridge, he sometimes called on his fellow students in their rooms to ‘tick them off for not being proper Christians’.14 Until 1925 he had always thought that he could be both a missionary and scientist.

So what caused the total change in Louis, not only in his life’s ambition, but also in his worldview? He tells us in his autobiography: ‘ … I had become firmly convinced of the truth of the theory of Evolution as distinct from Creation as described in Genesis … .’15

Conclusion

Louis Leakey’s life played out on the world stage a tragedy which is, sadly, all too common. So often, godly parents fail to see that the ‘science’ teaching that their offspring are imbibing is all within a framework that rejects Bible history. It is based on a philosophical belief system that rejects direct divine action. But the Bible’s history is foundational to the Gospel. So it is not surprising that such students usually end up rejecting their childhood belief—especially those brighter ones who can spot the inconsistencies of putting ‘faith’ and ‘reality’ in two separate boxes.

If only such parents were to arm and equip their family with a biblical worldview, one which lets them connect the evidence of the real world to the Bible, what a difference such real science would make!

Louis Leakey died in London on 3 October 1972, aged 69. As with all of us, his choices were relevant to both his temporal and his eternal destiny. Honoured by the world which is ‘passing away’, he missed being ‘the man who does the will of God’ and who ‘lives for ever’ (1 John 2:17).

References

- Known as ‘volcanic glass’, obsidian fragments can break with edges as sharp as the finest scalpels. Return to text.

- Cole, S., Leakey’s Luck, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, London, p. 37, 1975. Return to text.

- Darwin, C., The Descent of Man, John Murray, London, p. 155, 1887. Return to text.

- Leakey, L.S.B., Adam’s Ancestors, Methuen & Co. Ltd., London (1934, rewritten 1953). Most of the drawings are of flint-type hand-tools. Return to text.

- In England in the 1930s, the only sure ground for divorce was adultery. Return to text.

- Morrel, V., Ancestral Passions, Simon & Schuster Ltd., New York, p. 344, 1995. Return to text.

- Ref. 6, p. 533. Return to text.

- It is now called Australopithecus (or Paranthropus) boisei. Return to text.

- Leakey, L.S.B., Finding the world’s earliest man, National Geographic 118(3):420–435, September 1960. Return to text.

- See interview with ‘human evolution’ authority Dr Fred Spoor on CMI’s video The Image of God. Return to text.

- Leakey, L.S.B., White African, Hodder and Stoughton, London, p. 68, 1937. Return to text.

- Ref. 11, pp. 82–83. Return to text.

- Ref. 11, pp. 186–188. Return to text.

- Ref. 6, p. 28. Return to text.

- Ref. 11, p. 161. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.