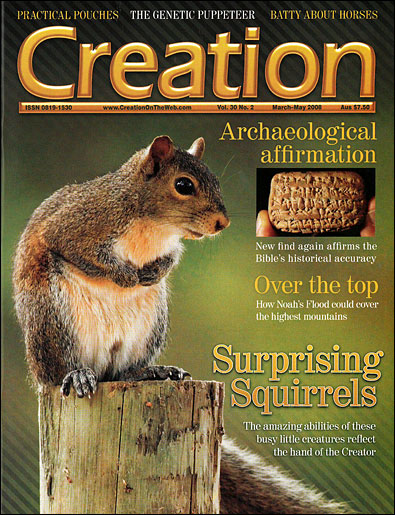

Squirrels!

Walking along a leafy forest trail, my students and I paused to look up at a particularly large tree. What happened next left the kids in awe. A little bug-eyed southern flying squirrel (Glaucomys volans) peered out from one of the cavities and proceeded to climb to the top of the tree. With one mighty push of his legs he launched himself into space. Gliding through the air he soared approximately 10 m (33 ft), using his tail as a rudder, twisting and turning to maneuver around branches. Fleshy foot pads cushioned his impact and sharp claws allowed him to cling to the tree.1 And, just as suddenly as he appeared, he was gone.

Flying squirrels are a small group within the greater squirrel clan. Squirrels are classified in the family Sciuridae which includes approximately 21 Genera and 117 species.2 The three major groups of squirrels include the flying, tree and ground squirrels. They are found in many places of the world except Australia, Madagascar, the polar regions and South America. Ecologically, they are important sources of food for other animals and some may aid forest tree regeneration and dispersal of fungal spores that are beneficial to ecosystem health.

Origin of squirrels

Biologists have reported that the details of squirrel origins are unclear and difficult to piece together.3 Philosophical naturalism is the prevailing worldview of evolutionary scientists who assume that squirrels are products of random mutations and natural selection over long periods of time. Unfortunately, this perspective is paraded and disguised as science for a public that often does not realize the religious basis and implications of such naturalistic philosophy.

Sadly, some Christians also think that they are hearing ‘science’, not realizing it is instead an unbiblical interpretation of the science.

Instead of assuming that life arose from accidental processes, Christians should begin with the Creator’s eyewitness account, in Genesis, and build their scientific investigations upon the presupposition that life was designed, and the various kinds of living things were designed to reproduce after their kind. Thus all creatures alive today are descended from the original created kinds.

So, are all the various squirrel species today members of the same created kind? One method for determining if species are related—i.e. that they belong to the same kind—is to note their ability to hybridize.4 Hybrids have been documented for the eastern gray squirrel (Sciurus carolinensus), a native of the Eastern United states and Canada, and the Eurasian red squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris) from Europe and Asia.5

This suggests that even though they have been classified as two separate species, found in different parts of the world, they are really part of the same created kind. Different ground squirrel species of the genus Spermophilus are also able to hybridize, suggesting that they too are descended from one or more pairs of the original created kind.6 Just exactly how the flying, ground and tree squirrels have diversified and how many original squirrel pairs were created are unknown.

The fossil evidence of the earliest tree squirrel-like creatures is scant and based on teeth. They include tree squirrel-like fossils, unearthed in France (Sciurus dubious), and specimens of the genus Protosciurus discovered in North America.2 The evidence suggests that these fossils are of fully-formed squirrels that had similarities with modern tree squirrels. Interpretations for how current squirrel populations have diversified from the creatures that left these fossil remnants are consistent with the views of both creationist and evolutionist biologists. However, only the biblical worldview is consistent with the amazing and mysteriously complex design features of squirrels.

Tree squirrels

Tree squirrels are the aerial acrobats of the clan. Their bones are lightweight and their hind legs are long and powerful for speed and ascension. Many also have different sets of sensory hairs, which they use to orient themselves. These are located on their head, on the underside of the body and at the base of the tail.2

Many species build a nest, called a drey, which is made of twig frameworks and an intricate layer of leaves, interlocked and woven together to produce a watertight and insulated home.

Their bushy tail allows them to balance but is also used for body temperature regulation. They can wrap themselves with it and some have a complicated system of veins and arteries designed to decrease heat loss to the environment and conserve energy. This system is known as counter-current heat exchange—a well-known engineering design that’s often found in nature. Veins and arteries constrict to intercept heat on the way to the tail, keeping the tail temperature considerably lower than the body cavity while adding heat to the blood returning to the core.7

Ground squirrels

The ground squirrels include the marmots and chipmunks (see photo). Among the many things that set them apart is their genetic programming for survival in extremes of heat and cold. For example, the cape ground squirrel (Xerus inauris) uses its tail like a parasol to regulate heat in the hot regions of South Africa. This behavior allows them to reduce the temperature experienced by their bodies by 5 Celsius degrees (9F°), enabling them to extend their feeding activity by four hours.8

Hibernation

In extremely cold environments, ground squirrels may descend into a deep dormancy called hibernation. Depending on the squirrel, they are active either by day or at night, choosing these times to forage and store food. An internal clock tells them when to wake up or go to sleep. This circadian clock is based on certain body processes that repeat in a 24-hour cycle. The system allows them to distinguish day from night and the clock can be reset with environmental cues. Circadian clocks are found in many other creatures, including humans.9

The ability to hibernate also requires that squirrels detect seasonal changes and know when, how much and how long to gather food. The only way to do these things is to have an internal calendar (circannual calendar). The ground hog (Marmota monax) feeds (mostly on grass) throughout the spring and summer. But, come late summer, his internal calendar kicks in and then he really ‘pigs out’, building up the fat that will be his energy source for the winter ahead. This calendar controls when his body shuts down for the season and when to fire it up again.

Once the cold hits, the squirrel heads for its place of inactivity called a hibernaculum. Here, complicated and finely tuned body processes take place and cause an almost complete body shutdown. For many squirrels, body temperatures plummet from 37°C (99°F) to near 0°C (32°F).

Champion of the clan

The champion hibernator of the squirrel clan is the Arctic ground squirrel (Spermophilus parryi) of the northern tundra. Because of the severe cold, the permafrost, or permanently frozen soil, is just a few centimetres from the surface. Permafrost stops the squirrel from digging very deep and forces it to hibernate in soil with below freezing temperatures, even as low as –15°C (5°F). Core body temperatures have been measured at –2 to 3°C (28–37°F), respiration and heartbeat are undetectable, brain wave activity is zero and only a trickle of blood is entering the brain.10 How they are able to survive is still a mystery. If these animals were human they would be pronounced dead.

Ground squirrels do not stay dormant the whole time but wake up periodically. It takes about a day for them to reach their active body temperature of 37°C (99°F). It will take another day to return to their near-death condition. They may do this a dozen times and no one knows why they do this, because in total it can use up one-half of their initial winter energy reserves.9 Interestingly, as their body temperature increases, captive animals move toward REM (Rapid Eye Movement) sleep. Does warming up allow them to fight sleep deprivation?

Stroke patients suffer brain damage from lack of oxygen and glucose getting to the brain. However, a squirrel’s brain shuts down without damage. Do they warm up to oxygenate the brain?10 If humans are inactive for long periods, bone density and muscle mass decrease. Amazingly, this is not an issue with dormant squirrels.

Everything about squirrels—their origin, their abilities in the tree tops and on the ground, their capacity to occupy places of extreme heat and cold—speak of creation, not evolution over eons of time.

References and notes

- Saunders, D.A., Adirondack Mammals, Adirondack Wildlife Program, State University of New York, College of Environmental Science and Forestry, Syracuse University Press, New York, USA, p. 96, 1998. Return to text.

- Squirrels and relatives III: Tree squirrels, Answers.com, <www.answers.com/topic/squirrels-and-relatives-iii-tree-squirrels-biological-family?cat=technology>, 5 October 2007. Return to text.

- Thorington, R.W. Jr., Pitassy, D. and Jansa, S.A., Phylogenies of flying squirrels (Pteromyinae), Journal of Mammalian Evolution 9(1/2):99–136, 2002. Return to text.

- Batten, D., Ligers and wholphins—what next?, Creation 22(3):28–33, 2000. Return to text.

- Gray, A.P., Mammalian Hybrids, Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux, 1972; <www.bryancore.org/cgi-bin/hdb.pl?field=Genus&query=sciurus>. Return to text.

- Cothran, E.G. and Honeycutt, R.L., Chromosomal differentiation of hybridizing ground squirrels (Spermophilus mexicanus and S. tridecemlineatus), Journal of Mammalogy 65(1):118–122, 1984. Return to text.

- Muchlinski, A. and Shump, A., The sciurid tail: a possible thermoregulatory mechanism, Journal of Mammalogy 60(3):652–654, 1979. Return to text.

- Bennett, A.F., Huey, R.B., John-Alder, H. and Nagy, K.A., The parasol tail and thermoregulatory behavior of the cape ground squirrel Xerus inauris, Physiological Zoology 57(1):57–62, 1984. Return to text.

- Heinrich, B., Winter World: The Ingenuity of Animal Survival, Harper-Collins, New York, p. 84, 2003. Return to text.

- Ref. 9, p. 106. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.