Make believe knowledge

Wikipedia: Szczepan1990

Everybody ‘believes’. It is as innately human to believe certain things as to know certain things, and very often the distinction between the two is blurred. Even those who would tell us that the only things we can know truly are those things that can be scientifically, empirically shown to be true, are expressing a belief. Their very assertion is one of blind faith and is even self-refuting; it cannot be empirically verified and thus there is no reason to accept it as true under its own criteria. They believe by faith that their dogma is true, and by that belief undermine the very foundation they attempt to build.

Like it or not, we all believe. Even when the things we believe have been established on empirical evidence, this is usually based not on our own observations of the evidence, but on acceptance of the findings of others. This is especially so in this increasingly specialised world.

The study of why we believe/know the things we believe/know is called epistemology. We believe some things by conditioning, they are the things we have been taught to believe. We believe them because our parents, our culture or someone we respect or who was influential in our lives believed them. We might call this conformity. We also believe some things out of pure contrariness to what others believe. We might like to label this as non-conformity although some might call it rebellion, often in reaction to beliefs of parents or teachers, regardless of its credibility or lack thereof.

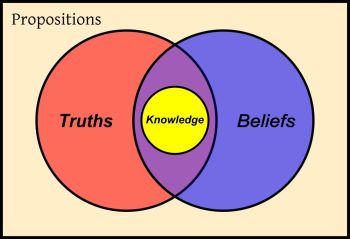

If we are honest, we would have to admit that even some of the things we ‘know’ to be true, are actually beliefs we have absorbed from the common consensus of our family, culture, club, collegiate or congregation. This is knowledge that we have absorbed passively or under pressure. The approval of our peers, acceptance, funding, prestige, promotion and fear can all be powerful influences of what we choose to believe.

Hopefully most people will go beyond these factors to personally think through and verify the reasons why they believe certain things; particularly regarding really important questions such as where we come from, purpose in life, existence or extinction beyond the grave and so on. The answers to these questions are literally a matter of life and death; both physically and temporally; spiritually and eternally, if our existence does indeed continue beyond the grave. But even in these important categories, there are so many facets involved, that to some degree or another, we will always believe certain things to be true based on the authority of others. The reason we choose to believe these authority figures may be due to their academic credentials, their fame, their ability to influence our personal circumstances, their leadership and communication skills, their achievements in life, how broadly their teachings have been accepted by society or many other possible criteria. This is true of both religious and secular belief systems.

These authority figures (or in some cases the Controllers envisaged by Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World) have included such people as Plato, Aristotle, Hitler, Muhammad, Marx, Darwin, Freud, Oprah and even Jesus Christ. Probably the most common basis of belief, whether the faithful like to admit it or not, is that the ‘majority’ (as in “everybody knows” or “most scientists accept”) believe it. Conforming to the beliefs and biases of our peers and contemporaries is a powerful motivator. Or rather, going against the flow of professional or public opinion incurs a cost that demotivates questioning the status quo. There is a feeling of strength and even invincibility in numbers that helps us avoid as unnecessary the need to research something objectively ourselves. Based on these motives for belief, what are some of the great ‘clangers’ that ‘everybody’ has believed at different times in history?

In the religious realm, indulgences and scores of heavenly virgins awaiting martyrs (murderers) come to mind. But there have also been many dogmas in the scientific realm that have in the course of time been proven to be profound mistakes, but were nevertheless accepted by the scientific elite and therefore by the public at large. These theories were zealously defended and opponents fiercely resisted until the body of evidence against them became too overwhelming for continued defence.

The Ptolemaic and Aristotelian idea of geocentrism, the theory that the earth was at the centre of the universe and all the heavenly bodies revolved around it is a famous case in point, believed for almost 2000 years. Most educated Greeks from about the 4th century BC, believed that the earth was a sphere around which the heavens revolved. As the Roman Catholic church increased in influence from about the 4th century AD, it did so in a philosophical and scientific environment that had wholly accepted this system. Islamic astronomers later also accepted the model. As the heavens were increasingly explored and discovered, ever more complex models were developed to continue to prop up a geocentric system.

Due mainly to perceived philosophical implications, as Copernicus and Galileo developed their heliocentric models in the 16th and 17th centuries, they were strongly opposed by the Catholic church. It was the creationist Johannes Kepler who hit the final nail in the geocentric coffin with his combination of a heliocentric system and elliptical planetary motion.

Aristotle was also the most influential founder of another scientific view that held sway for 2,000 years before being proven false by another creationist. That theory was the spontaneous generation of life from non-life or abiogenesis. Without the benefit of modern microscopes, he believed that some plants and animals, under certain circumstances, were ‘self-generated’ and ‘grow spontaneously’. This was a theory that was eagerly accepted by the early evolution theorists as it provided a mechanism to get the evolutionary ball rolling. It was Louis Pasteur who by empirical experiment and observation finally put the myth of spontaneous generation to rest in the same year as Darwin’s publication of Origin of Species. Since then all biological and medical science, whether by evolutionists or creationists, is done on the assumption of biogenesis, that life only comes from life. This left evolutionists with a quandary of how life, upon which natural selection was to do its magical work, began. An evolutionist today has to still cling to some form of the unscientific notion of abiogenesis.

Big beliefs have big consequences and this is nowhere more evident than in the effect that Darwin’s ideas had on the western world’s perception of race in the 19th and 20th centuries. As the late Stephen Jay Gould, an evolutionist himself, recognised, although racism has always existed in some form or another, it was Darwinism that led to a profound increase in racist ideas and beliefs.1 Darwin predicted that if his theory were true, a subjugation and even extermination of the ‘lower races’ was inevitable. Most scientists of the late 19th through to the middle of the 20th century were Darwinian in their beliefs and promoted scientific racism as a logical consequence. Most notable among these were people like Ernst Haeckel in Germany and Henry Fairfield Osborn in America. Influenced by these scientists, the public at large in the western world were increasingly infatuated with their own ‘superiority’. Scientific racism, imperialism and rapacious colonialism became dominant themes of both sides of the turn of the 20th Century. The extermination of races forecast by Darwin was actively pursued in early race ‘laboratories’ like German South West Africa and reached its horrifying climax in the death camps of Nazi Germany. While these horrors as well as new scientific discoveries made mainstream scientists discard scientific racism in the early decades after WWII, it remains a fact that scientists and the broader public were as uniformly racist prior to this change as they are, thankfully, anti-racist today.

If ever a theory deserved to be abandoned based on its fruits, Darwinism is that theory, and yet while racism has been largely discarded, the core ideas remain. I guess in the minds of its adherents, the benefits of the theory, namely, the ‘death of God’, outweigh its inconvenient consequences like the millions killed in racial genocide last century. Darwinian evolution does not even have the benefit of empirical verification.

Perhaps you choose to believe in the dominant ideas of this age, foremost among them being evolution, largely for their cultural dominance. If so, you are in the good company of those who believed in geocentrism, abiogenesis and Darwinian race theory as well as many other ‘scientific’ discards that were once the ruling paradigms of their day.

I choose to believe the teachings of the most qualified and accredited individual to ever walk this earth, Jesus Christ the Son of God. The Creator, the Logos, an authentic teacher, instant healer of disease and disability, raiser of the dead, calmer of the seas. He was the greatest non-conformer to the dominant ideas of this world and paid for it with His life. But in the most profound of His credentials, He arose from the grave. Millions have also gone against the dominant beliefs of their culture and age, to put their faith in Him and many have paid the ultimate price for their non-conformity.

We all ‘believe’ many things. As you look for solid ground upon which to place your faith, are you looking for reality or acceptance? For Truth or tenure? For substance or comfort? For eternity or for the moment? Jesus Christ is “the Way, the Truth and the Life”.

References

- “Biological arguments for racism may have been common before 1850, but they increased by orders of magnitude following the acceptance of evolutionary theory.” (Gould, S.J., Ontogeny and Phylogeny, Belknap-Harvard Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, pp. 127–128, 1977.) Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.