Journal of Creation 27(2):9–10, August 2013

Browse our latest digital issue Subscribe

Non-Christian philosopher clears up myths about Augustine and the term ‘literal’

There has been no shortage of attempts by theistic evolutionists to reconcile acceptance of Darwinian evolution and a billions-of-years timescale with Genesis. It may be argued that all of the key players, such as Francis Collins1 and Karl Giberson,2 have a vested interest: they happen to be theistic evolutionists. As such, their bias motivates them to try to produce a narrative that incorporates both evolution and some semblance of a nod to biblical authority. However, Gregory Dawes, a philosophy professor and self-professed unbeliever, brings a unique perspective.3 He does not have any interest in either preserving the Bible’s authority or reconciling it with evolution, so his thoughts are instructive. In a recent article he asks, “Can the Bible’s account of human origins be interpreted in a way that is consistent with Darwin’s theory?”4

Biblical authority and science

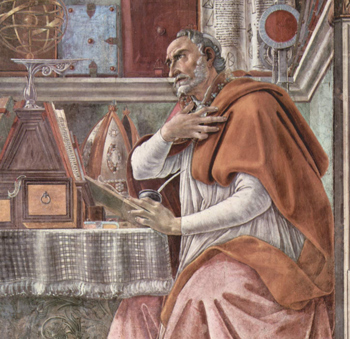

Dawes goes back to Augustine (AD 354–430), who was the first Christian writer to lay out principles for dealing with “apparent conflicts between the Bible and secular knowledge”,5 for some traditional principles of when the biblical text may be reinterpreted. These can be summarized:

- When a literal reading of the Bible and a proven fact about nature seem to conflict, we must seek an alternative reading of Scripture.

- However, when this conflict is over something less than certain, “the authority of the literal sense of scripture is to be preferred.”5

These principles have been used by both Catholics and Protestants throughout history. However, it’s not so simple with evolution. For example, there is a famous quote by Augustine that many theistic evolutionists love to throw at biblical creationists:

“Usually, even a non-Christian knows something about the earth, the heavens, and the other elements of this world, about the motion and orbit of the stars and even their size and relative positions, about the predictable eclipses of the sun and moon, the cycles of the years and the seasons, about the kinds of animals, shrubs, stones, and so forth, and this knowledge he holds to as being certain from reason and experience. Now, it is a disgraceful and dangerous thing for an infidel to hear a Christian, presumably giving the meaning of Holy Scripture, talking nonsense on these topics; and we should take all means to prevent such an embarrassing situation, in which people show up vast ignorance in a Christian and laugh it to scorn. […]

“If they find a Christian mistaken in a field which they themselves know well and hear him maintaining his foolish opinions about our books, how are they going to believe those books in matters concerning the resurrection of the dead, the hope of eternal life, and the kingdom of heaven, when they think their pages are full of falsehoods and on facts which they themselves have learnt from experience and the light of reason?

“Reckless and incompetent expounders of Holy Scripture bring untold trouble and sorrow on their wiser brethren when they are caught in one of their mischievous false opinions and are taken to task by those who are not bound by the authority of our sacred books. For then, to defend their utterly foolish and obviously untrue statements, they will try to call upon Holy Scripture for proof and even recite from memory many passages which they think support their position, although they understand neither what they say nor the things about which they make assertion.”6

But the key here is “knowledge … being certain from reason and experience”, or the “proven fact” in the summary. Dawes argues that for Augustine, evolution would have fallen far short of ‘certainty’. (Actually, patristics scholar Benno Zuiddam has documented that Augustine was a fervent ‘young-earth’ creationist, and far more ‘literal’ than most theistic evolutionists realize.7) Dawes concludes that compared to the Bible, considered to be the infallible Word of God by Christians, “there is a sense in which Darwinism—in common with all our best science—is ‘merely a theory’.”8,9 He points out:

“If Newtonian physics needed to be radically revised in the early twentieth century, then we should not assume that even our best theories are established beyond any possibility of doubt.”8

So the only way for Darwinist Christians to be consistent is to remove biblical authority from matters of science and history altogether. But this is problematic, because the Bible’s statements about theology and history are so closely intertwined. For example, Paul’s profound expositions of the Gospel are intimately connected to a historical Adam and Fall.10,11 And Jesus Himself taught on marriage by going back to a historical Adam and Eve, made “from the beginning of creation”, not billions of years after the beginning.12 One of Christianity’s central claims about God is that He has revealed Himself in history. Dawes concludes, “the hermeneutical question is a more difficult one than many theistic evolutionists appear to realize.”13

‘Literal’ interpretation

Dawes’ paper also provides useful information on this term. Modern informed creationists tend to disclaim that their hermeneutical method with the Bible is ‘literal’. That’s because they recognize that there are many different types of literature in the Bible—historical, poetic, prophetic, apocalyptic; and there are also plenty of figurative sections. So we tend to advocate a ‘plain’ interpretation, or, in technical terms, the grammatical-historical hermeneutic.14 The aim of this method is to read Scripture as its human authors and original audience would have understood it (so it could be termed an originalist approach). Nowadays, ‘literal’ often has the connotation of woodenly literalistic, and detractors of biblical creationists dishonestly knock down this straw man. However, no leading creationist is a ‘literalist’ in this sense, e.g. reading Jesus saying, “I am the door”, and thinking He had a knob and hinges.

However, Dawes documents that Medieval and Patristic interpreters likewise used the term ‘literal’ in a wider sense than ‘literalistic’.15 Their view of ‘literal’ interpretation could include a figurative meaning if that’s what the text taught. Thus, to them, the ‘literal’ meaning of “the windows of the heavens were opened” (Genesis 7:11) would include its metaphorical usage for a massive rainfall. Rather, the ‘literal’ meaning was contrasted with a spiritualized or mystical meaning not grounded in the text.16 That is, the ancient ‘literal’ interpretation corresponds rather well to the modern grammatical-historical hermeneutic. Actually, the standard Chicago Statement on Biblical Hermeneutics has very similar usage:

“Article XV

We affirm the necessity of interpreting the Bible according to its literal, or normal, sense. The literal sense is the grammatical-historical sense. That is, the meaning which the writer expressed. Interpretation according to the literal sense will take account of all figures of speech and literary forms found in the text.”

Similarly, the eminent evangelical Anglican theologian James Innell Packer (1926–) explained this usage in depth in his classic ‘Fundamentalism’ and the Word of God.17 For example, he cites the great Reformer and Bible translator William Tyndale (1494–1536):

“Thou shalt understand, therefore, that the scripture hath but one sense, which is but the literal sense. And that literal sense is the root and ground of all, and the anchor that never faileth, whereunto if thou cleave, thou canst never err or go out of the way. And if thou leave the literal sense, thou canst not but go out of the way. Nevertheless, the scripture uses proverbs, similitudes, riddles, or allegories, as all other speeches do; but that which the proverb, similitude, riddle or allegory signifieth, is ever the literal sense, which thou must seek out diligently.”

Conclusion

Dawes’ paper is a refreshingly honest and intellectually rigorous look at theistic evolution. But it is not the first time unbelievers have pointed out the inconsistencies between evolution and a traditional view of biblical authority. It is also honest about what a real ‘literal’ interpretation should be: what evangelicals call the grammatical-historical approach. Understanding the history of interpretation throughout the church age should help avoid misunderstandings and refute straw man arguments.

References and notes

- Weinberger, L., Harmony and discord: Review of The Language of God: A Scientist Presents Evidence for Belief (2006) by Francis S. Collins, J. Creation 21(1):33–37, 2007; creation.com/collins-review. Return to text.

- Cosner, L., If evolutionists inspired Scripture: Review of Giberson, K., Seven Glorious Days: A Scientist Retells the Genesis Creation Story by Karl Giberson, J. Creation 27(2):37–38 2013. Return to text.

- Compare Weinberger, Preaching to his own choir: Review of Can a Darwinian Be a Christian? The Relationship Between Science and Religion (2001) by Michael Ruse, J. Creation 19(2):42–45, 2005; creation.com/ruse2. Return to text.

- Dawes, G.W., Evolution and the Bible: The hermeneutical question, Relegere 2(1):37–63, 2012. Return to text.

- Dawes, ref. 4, p. 43. Return to text.

- Augustine, The Literal Meaning of Genesis (De Genesi ad litteram) 1(19):39,

AD 401 to 415; translation by Taylor, J.H., in Ancient Christian Writers 2:42–43, Paulist Press International, 1982. Return to text. - Zuiddam, B., Augustine: young-earth creationist, J. Creation 24(1):5–6, 2010; creation.com/augustine. Return to text.

- Dawes, ref. 4, p. 48. Return to text.

- It’s ironic that an unbeliever is basically using ‘Evolution is just a theory’, a phrase commonly used by less experienced creationists that irritates evolutionists no end. However, these evolutionists have a point—neither these creationists nor Dawes seem to realize that a ‘theory’ in science is something well attested, such as ‘theory of gravity’. So CMI lists ‘Evolution is just a theory’ as one of the ‘Arguments creationists should NOT use’, creation.com/dontuse. Yet it’s notable that an unbeliever like Dawes, who must logically believe in a form of evolution, realizes that it’s far from a certainty. Return to text.

- Cosner, L., Romans 5:12 21: Paul’s view of a literal Adam, J. Creation 22(2):105–107, 2008; creation.com/romans5. Return to text.

- Cosner, L., Christ as the last Adam: Paul’s use of the Creation narrative in 1 Corinthians 15, J. Creation 23(3):70–75, 2009; creation.com/1-corinthians-15. Return to text.

- Wieland, C., Jesus on the age of the earth, Creation 34(2):51–54, 2012; creation.com/jesus_age. Return to text.

- Dawes, ref. 4, p. 61. Return to text.

- Kulikovsky, A.S., The Bible and hermeneutics, J. Creation 19(3):14–20, 2005; creation.com/hermeneutics. Return to text.

- Dawes, ref. 4, pp. 45–47. Return to text.

- Dawes cites Nemetz, A., Literalness and the Sensus Litteralis, Speculum (A Journal of Medieval Studies) 34(1):76–89, 1959. Return to text.

- Packer, J.I., ‘Fundamentalism’ and the Word of God, Inter-Varsity Press, Downers Grove, IL, pp. 101–114, 1958. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.