Darwin’s critical influence on the ruthless extremes of capitalism

A review of the writings of the leading ‘robber baron’ capitalists reveals that many of them were influenced by the Darwinian conclusion that the strong eventually will destroy the weak. Their faith in Darwinism helped them to justify this view as morally right. As a result, they felt that their ruthless (and often illegal and lethal) business practices were justified by science. They also concluded that Darwinian concepts and conclusions were an inevitable part of the ‘unfolding of history’ and consequently practising them was not wrong or immoral, but was both right and natural.

Darwinism was critically important, not only in supporting the development and rise of Nazism and communism (and in producing the Nazi and communist holocausts), but also in the rise of the many ruthless robber baron capitalists that flourished in the late 1800s and early 1900s.1 As Julian Huxley and H.B.D. Kittlewell concluded, social Darwinism has led to many evils, including ‘the glorification of free enterprise, laissez faire economics2 and war, to an unscientific eugenics and racism, and eventually to Hitler and Nazi ideology’.3 A major aspect of this form of capitalism was the Darwinian belief which concluded that it is natural and proper to exploit without limits both ‘weaker’ persons and weaker businesses.

Social Darwinism/Spencerism

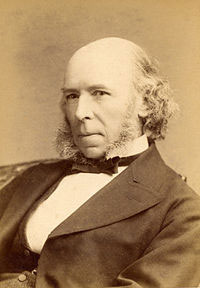

Herbert Spencer was one of Darwin’s most prominent disciples. Spencer, a radical eugenicist and social Darwinist, concluded certain races were inferior and eventually would be ‘selected into extinction’. He felt that the same things would happen to weaker individuals. Many of Spencer’s books were best sellers. They were used as college texts in many universities, and influenced many of our nation’s top business leaders. His books and articles

‘… made him world famous by 1870 and, in America, his star rose higher than that of his countryman Charles Darwin. A very successful American magazine, the Popular Science Monthly, was founded … as a forum for Spencer’s ideas. Industrialist Andrew Carnegie gave a dinner in his honor, [that was] attended by everybody who was anybody during the Gilded Age. Yet today, Spencer’s works are unread, his name greeted by yawns and he is no hero even to philosophers or evolutionists … Spencer … became best known for providing an ethical rationale for laissez-faire industrial capitalism. Although the idea became known as Social Darwinism, it was really Social Spencerism.’4

Spencer concluded that social evolution would eliminate the less fit or weaker individuals

‘… while rational men abstained from interfering with the inexorable “laws” of evolution. The result, he believed, would be an evolved society that functioned smoothly and for the general good of its (future) members. Perpetual progress was the rule of evolution, with individual and social happiness its eventual goal.’4

His ideas also had clear implications in other areas as well. The late Isaac Asimov noted that Darwinism can be used to justify ignoring normal social responsibility to the unemployed or needy.

‘In 1884 [Spencer] argued, for instance, that people who were unemployable or burdens on society should be allowed to die rather than be made objects of help and charity. To do this, apparently, would weed out unfit individuals and strengthen the race. It was a horrible philosophy that could be used to justify the worst impulses of human beings.’5

Common working conditions in the 1800s and early 1900s

The robber barons’ lack of concern for the social welfare of the community, and even their companies’ own workers, ruined millions of lives. Injuries on the job due to unsafe working conditions were a major cause of death and permanent injury for decades during this period. The yearly total of such deaths, injury and illness in the USA around 1900 has been estimated at around a million workers.6

Conditions such as unguarded motor belt drives and power shafts on machines were the norm, and routinely caused the loss of fingers, hands and even whole limbs. For the workers, loss of body parts was almost an inevitable result of a lifetime of factory or industrial employment. Surveys of workers revealed that over half sustained serious injuries, ranging from loss of appendages to loss of vision or hearing, during their work career. In some vocations, virtually every worker suffered injury. For example almost all workers who manufactured stiff-brimmed hats suffered from mercury poisoning, and almost all workers who painted radium dials sooner or later were stricken by cancer.7

Even when the employers were fully aware of the dangers their workers faced, most did little or nothing to improve the conditions of their factory. Many steel mill foundry workers worked 12 hour shifts in 47°C heat for $1.25 a day.8 President Harrison said in 1892 that the average American worker was subject to danger every bit as great as soldiers in war.9 Upton Sinclair immortalized the atrocious conditions for workers in the meat packing industry in his now classic book TheJungle, first published in 1906.10 TheJungle was widely considered a major catalyst in changing labour laws, and eventually was translated into 17 languages and sold millions of copies. This book so moved Theodore Roosevelt that he worked tirelessly to reform business avarice. The result included the passage of a stream of important labour laws, as well as the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act.

Human lives were considered so expendable by many capitalists that hundreds needlessly died laying railroad track alone.11 They died from poor living conditions provided by the railroad, from the heat and cold, from disease, and from Indian attacks. An excellent example of this exploitation occurred when J.P. Morgan purchased 5,000 defective rifles for $3.50 each and sold them to the army for $22.00 each. The defect caused the rifle to occasionally shoot off the thumbs of its users.11 The victims sued, and a federal judge upheld the sale as legal and appropriate. In this case, as was common then, the courts usually sided with the robber barons.12

Many judges were schooled in Darwinism and, as they often also accepted the survival-of-the-fittest ideology, they concluded that the lives of common men and women were worth little. As one employer noted when asked to build roof protection for his workers, ‘Men are cheaper than shingles’.12 The ruthlessness of the capitalists was so extreme that eventually governments the world over passed hundreds of laws against these common practices. Laws against monopolies are only one example of a result of the corruption common during this era of American history.

From Christianity to Darwinism

Many of the robber barons were reared as believers in God, but either had abandoned that belief or modified it to include the ideas of Darwin and Spencer about survival of the fittest. Andrew Carnegie, in his day reported to be the richest man in the world and the undisputed leader of the steel industry, also once professed a belief in Christianity, but abandoned it for Darwinism and became a close friend of the famous social Darwinist Herbert Spencer. He evidently was introduced to Darwinism by a group of ‘free and enlightened thinkers … seeking a new “religion of humanity”’ that met in the home of a New York University professor.13 Carnegie stated in his autobiography that when he and several of his friends came to doubt the teachings of the Bible,

‘… including the supernatural element, and indeed the whole scheme of salvation through vicarious atonement and all the fabric built upon it, I came fortunately upon Darwin’s and Spencer’s works … . I remember that light came as in a flood and all was clear. Not only had I got rid of theology and the supernatural, but I had found the truth of evolution. “All is well since all grows better” became my [laissez-faire] motto, my true source of comfort. Man was not created with an instinct for his own degradation, but from the lower he had risen to the higher forms. Nor is there any conceivable end to his march to perfection.’14

Spencer, not Darwin, was actually the originator of the phase ‘survival of the fittest’.15

Darwinism became a religion for many industrialists. An excellent example is:

‘Progress through evolution, both biological and technological, bringing nature and man, “the machine and the garden”, toward perfect harmony—this was to be the essence of Carnegie’s faith in the ultimate perfectibility of the universe, and he would hold to that faith for the next thirty-five years.’16

For Carnegie, Spencer became a god. In Carnegie’s own words, Spencer was ‘the greatest mind of his age or any other’. And in Spencer’s ‘ponderous volumes … lay the final essence of all truth and knowledge’.17

Many capitalists did not discard their belief in God, but instead tried to blend it with Darwinism. The result was a compromise somewhat like theistic evolution. Most American businessmen were probably not consciously social Darwinists, but rather tended to attribute their success to more lofty personal traits such as their intelligence, skill, industry and virtue, rather than as a result of ruthlessly

‘… trampling on their less successful competitors. After all, most of them saw themselves as Christians, adhering to the rules of “love thy neighbor” and “do as you would be done by”. So, even though they sought to achieve the impossible by serving God and Mammon simultaneously, they found no difficulty in accommodating Christianity to the Darwinian ideas of struggle for existence and survival of the fittest, and by no means all of them consciously thought of themselves as being in a state of economic warfare with their fellow manufacturers.’18

John D. Rockefeller reportedly once stated that the ‘growth of a large business is merely a survival of the fittest … the working out of a law of nature …’.19 The Rockefellers, while maintaining a Christian front, fully embraced evolution and dismissed Genesis as mythology.20 When a philanthropist pledged $10,000 to help found a university to be named after William Jennings Bryan, John D. Rockefeller Jr retaliated the very same day with a $1,000,000 donation to the openly anti-creationist University of Chicago Divinity School.21

Darwinism inspired communism and archcapitalism

It is well documented that Darwinism inspired not only Hitler, but also Stalin and Lenin. That evolution inspired both communists and archcapitalists is not as surprising as it may first appear. Both openly opposed the core values of Christianity, and were only on different sides of the so-called ‘class struggle’ that was believed to be an inevitable part of history.22 Morris and Morris also noted that both the left wing Marxist-Leninists and the right wing ruthless capitalists were anti-creationists and ‘even when they fight with each other, they remain united in opposition to creationism …’.23

Rachels noted that it was shortly after Darwin published his landmark Origin of Species in 1859 that ‘the survival of the fittest’ theory in biology was interpreted by capitalists as ‘an ethical precept that sanctioned cut-throat economic competition’.24,25

Carnegie, from about 1870 onward, ‘loudly trumpeted to the world—in public speeches, books, and articles, and in private conversations, and personal letters—his intellectual and spiritual indebtedness to Herbert Spencer’.26

‘Not only in his published articles and books but also in his personal letters to business contemporaries, Carnegie makes frequent and easy allusions to the Social Darwinist credo. Phrases like “survival of the fittest”, “race improvement”, and “struggle for existence” came easily from his pen and presumably from his lips. He did see business as a great competitive struggle and he was always painfully aware of the weak who did not survive.’27

The philosophy expressed by Carnegie was embraced not only by Rockefeller and the railroad magnates such as James Hill, but probably most other capitalists of their day as well.28 Even ‘Henry Ford, America’s preeminent capitalist’, Levine and Miller, ‘found in Darwinism the perfect rationale for the free-enterprise system’.29 The marriage of Darwinism and capitalism is best expressed by an incident that occurred on Spencer’s trip to America. On his way back to England, the following incident occurred.

‘However imperfect the appreciation of the guests for the niceties of Spencer’s thought, the banquet showed how popular he had become in the United States. When Spencer was on the dock, waiting for the ship to carry him back to England, he seized the hands of Carnegie and Youmans. “Here”, he cried to reporters, “are my two best American friends”. For Spencer it was a rare gesture of personal warmth; but more than this, it symbolized the harmony of the new science [of social Darwinism] with the outlook of a business civilization.’30

Historian Gertrude Himmelfarb noted that Darwinism was accepted rapidly in England (but was resisted for decades in France) in part because it justified the greed of the robber barons.

‘The theory of natural selection, it is said, could only have originated in England, because only laissez-faire England provided the atomistic, egotistic mentality necessary to its conception. Only there could Darwin have blandly assumed that the basic unit was the individual, the basic instinct self-interest, and the basic activity struggle. Spengler, describing the Origin as “the application of economics to biology”, said that it reeked of the atmosphere of the English factory … natural selection arose … in England because it was a perfect expression of Victorian “greed-philosophy”, of the capitalist ethic and Manchester economics.’31

Milner noted that applying social Darwinism to the capitalism that was common among American businessmen elevated the

‘… traditional virtues of self-reliance, thrift and industry to the level of “natural law”. Based more on the writings of Herbert Spencer than of Charles Darwin, its proponents urged laissez-faire economic policies to weed out the unfit, inefficient and incompetent.’32

Use of Darwinism to justify ruthless capitalism

One of social Darwinism’s leading spokesmen was Princeton University professor William Graham Sumner, who concluded that millionaires were the ‘fittest’ individuals in society, and therefore

‘… deserved their privileges. They were “naturally selected in the crucible of competition”. Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller agreed and espoused similar philosophies they thought gave a “scientific” justification for the excesses of industrial capitalism.’32

Many other prominent professors supported the application of the ‘survival of the fittest’ philosophy to society. In a study of sociologists, Rosenthal found that sociologists Cooley, Sorokin, Sumner, Ross, and even Park all adhered to biological racist doctrines that justified and even encouraged survival of the fittest social policy.34 Biogenetic doctrines historically had the effect of promoting an attitude of acceptance towards radical capitalism, racism, sexism and even war.33 Rosenthal noted that this was true even though no scientific evidence exists that human social behaviour at its base is biogenetic, or that business/social competition, male dominance, aggression, territoriality, xenophobia, and even patriotism, warfare and genocide are genetically based human universals.33 Nonetheless, biogenetic doctrines occupied a prominent place throughout most of American sociological academic history.

Many Darwinians concluded that for a business to survive, it must follow the laws of Darwinism, and to ignore them could lead to extinction just as occurs in the biological world. Asma observed:

‘Nature unfolds in such a way that the strong survive and the weak perish. Thus, the economic and social structures that survive are “stronger” and better, and those structures that don’t were obviously meant to founder. It is better that capitalism has survived the Cold War just as it was better that the mammals survived the Mesozoic Era when dinosaurs became extinct. “How do we know that capitalism is better than Communism and the mammal is better than the dinosaur? Because they survived, of course”’ [emphasis in original].34

Millionaire Houston oilman Michel Halbouty, who was typical of the robber barons, justified his ruthless exploits by reasoning, ‘As in nature, the principle of survival of the fittest will prevail’.35 Robber baron capitalists often concluded that, because survival of the fittest was the inevitable outcome of history, their behaviour therefore was justified by ‘natural law’.36 The result was a level of ruthlessness in business practices that rose even to the extent of murder.

Although many robber barons gave away large sums of money, their Darwinian ideas even affected them in this area. Carnegie gave away $125 million from 1887 to 1907 alone, but ‘none of it went for the direct relief of the unfortunate classes. As a good Darwinian he saw no reason for trying to save the unfit … . Throwing money into the sea was more preferable’.36 The robber barons did not see Darwinism as necessarily a negative force, but in the words of the President of Clark University, G. Stanley Hall:

‘Nothing so reinforces optimism as evolution. It is the best, or at any rate not the worst, that survive. Development is upward, creative, and not de-creative. From cosmic gas onward there is progress, advancement, and improvement.’37

Several studies have documented the important contribution of Darwinism, especially as developed by Spencer, to laissez-faire capitalism. An analysis of the Anthracite Coal Strike Commission (1902/03) hearings found ‘… the coal trust preached a social Darwinist ideology, conflating “survival of the fittest” with freedom and individual rights’.38 This study concluded that ‘the popularity of social Darwinism in the US national ideology should be comprehended as an innovation of corporate capitalism’.38

Darwinian ideas persist in business even today

The application of Darwinian concepts to business is still very much with us today. One of many possible examples is the manner in which Robert Blake and his co-authors (in their best-seller titled Corporate Darwinism) openly applied modern Darwinism to business. They concluded that business evolves, grows and expands in very predictable ways, specifically in defined stages—very much like the stages of human evolution.39 This ‘business evolution’ is natural; business, in keeping with Darwinian principles, either swallows the competition, or finds that it itself will be swallowed by that competition.

In a history of the Texas oil industry, Olien and Olien noted that even after World War II, many independent oilmen still believed that their economic success depended on the Darwinian struggle of the fittest philosophy.40 Yale professor David Gelernter quoted former Microsoft executive Rob Glaser who concluded the richest man in the world, Bill Gates, is ‘relentless, Darwinian. Success is defined as flattening the competition, not creating excellence’.41

Conclusion

Darwinism played a critical role in the development and growth of the ruthless form of capitalism best illustrated by the 19th-and 20th-century robber barons. While it is difficult to conclude confidently that ruthless capitalism would not have blossomed as much as it did if Darwin had not developed his evolutionary theory, it is clear that if Carnegie, Rockefeller and many other ruthless capitalists had continued to embrace the unadulterated Judeo-Christian world view of their youth, rather than becoming Darwinians, capitalism would not have become as ruthless as it did in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

No doubt other motivations, including greed and ambition, also were factors in the ruthlessness of the robber barons.42 Many were inclined to claim that their success was due to hard work, intelligence, thrift and sobriety.43 Their lives, though, often told other stories. Darwinism, however, gave many capitalists what appeared to be a scientific rationale that allowed capitalism to be carried to the extremes.30,44

Christianity, on the other hand, advocated behaviour quite in contrast to Darwinism:

‘… the Bible … preached no warfare of each against all, but rather a warfare of each man against his baser self. The problem of success was not that of grinding down one’s competitors, but of elevating one’s self—and the two were not equivalent. Opportunities for success, like opportunities for salvations, were limitless; heaven could receive as many as were worthy. Such a conception of the economic heaven differed from the Malthusian notion that chances were so limited that one man’s rise meant the fall of many others. It was this more optimistic view, that every triumph opened the way for more, which dominated the outlook of men who wrote handbooks of self-help.’45

If the robber barons would have lived consistently by this summary of Christianity, the abuses common in the 19th century likely would never have occurred

The harm that resulted from the application of Darwinism to business was a major motivator of William Jennings Bryan in his campaign to counteract the spread of Darwinism. Bryan ‘built his political career on denouncing the excesses of capitalism and militarism’, and ‘dismissed Darwinism in 1904 as “the merciless law by which the strong crowd out and kill off the weak” ’.46 History has shown Bryan’s concern was fully justified.

Acknowledgments

I want to thank Bert Thompson, Wayne Frair, Clifford Lillo, Aeron Bergman and John Woodmorappe for their helpful comments on an earlier draft of this article.

References

- Morris, H. and Morris, J.D., The Modern Creation Trilogy, Vol. 3, Society and Creation, Master Books, Green Forrest, 1996. Return to text.

- An economic theory, first propounded in the 18th century by Adam Smith, that held that individuals should be allowed to pursue their own interests, with as little government interference as possible. Property rights were sacred, landlords and employers were to be given almost complete control over tenants and workers. The prosperity of 19th century England is said to be grounded in laissez faire capitalism. The Difference Dictionary. Return to text.

- Huxley, J. and Kittlewell, H.B.D., Charles Darwin and His World, Viking Press, New York, p. 81, 1965. Return to text.

- Milner, R., The Encyclopedia of Evolution: Humanity’s Search for its Origins, Facts on File, New York, p. 415, 1990. Return to text.

- Asimov, I., The Golden Door: The United States from 1876 to 1918, Houston Mifflin Company, Boston, p. 94, 1977. Return to text.

- Hunter, R., Poverty, Torchbooks, New York, 1965. Return to text.

- Stellman, J. and Daum, S., Work is Dangerous to Your Health, Random House Vintage Books, New York, 1973. Return to text.

- Bettmann, O., The Good Old Days—They Were Terrible! Random House, New York, p. 68, 1974. Return to text.

- Bettmann, Ref. 8, p. 70. Return to text.

- Sinclair, U., The Jungle, Doubleday, Page & Company, New York, 1906. Return to text.

- Zinn, H., A People’s History of the United States, Harper Collins, New York, p. 255, 1999. Return to text.

- Bettmann, Ref. 8, p. 71. Return to text.

- Wall, J.F., Andrew Carnegie, Oxford University Press, New York, p. 364, 1970. Return to text.

- Carnegie, A., Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie (1920), edited Van Dyke, J.C., reprint, Northeastern University Press, Boston, p. 327, 1986. Return to text.

- Milner, 1990, p. 72. Return to text.

- Wall, Ref. 13, p. 366. Return to text.

- Wall, Ref. 13, p. 390. Return to text.

- Oldroyd, D.R., Darwinian Impacts, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, NJ, p. 216, 1980. Return to text.

- Ghent, W., Our Benevolent Feudalism, Macmillan, New York, p. 29, 1902. Return to text.

- Taylor, I.T., In the Minds of Men: Darwin and the New World Order, TFE Publishing, Minneapolis, p. 386, 1991. Return to text.

- Larson, E.J., Summer for the Gods: The Scopes Trial and America’s Continuing Debate Over Science and Religion, Basic Books, New York, p. 183, 1997. Return to text.

- Perloff, J., Tornado in a Junkyard, Refuge Books, Arlington, p. 226, 1999. Return to text.

- Morris and Morris, Ref. 1, p. 82. Return to text.

- Rachels, J., Created from Animals: The Moral Implications of Darwinism, Oxford University Press, New York, p. 63, 1990. Return to text.

- HsŸ, K., The Great Dying; Cosmic Catastrophe, Dinosaurs and the Theory of Evolution, Harcourt, Brace Jovanovich, New York, p. 10, 1986. Return to text.

- Wall, Ref. 13, p. 381. Return to text.

- Wall, Ref. 13, p. 389. Return to text.

- Morris and Morris, Ref. 1, p. 87. Return to text.

- Levine, J. and Miller, K., Biology: Discovering life, D.C. Heath, Lexington, p. 161, 1994. Return to text.

- Hofstadtler, R., Social Darwinism in American Thought, Beacon Press, Boston, p. 49, 1955. Return to text.

- Himmelfarb, G., Darwin and the Darwinian Revolution, W.W. Norton, New York, p. 418, 1962. Return to text.

- Milner, 1990, p. 412. Return to text.

- Rosenthal, S.J., Sociobiology: New Synthesis or Old Ideology? Paper presented at the 1977 American Sociological Association Convention, 1977. Return to text.

- Asma, S.T., The new social Darwinism: deserving your destitution, The Humanist 53(5):11, 1993. Return to text.

- Quoted in Olien, R.M. and Olien, D.D., Wildcatters: Texas Independent Oilmen, Texas Monthly Press, Austin, p. 113, 1984. Return to text.

- Wyllie, I., The Self-Made Man in America, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, p. 92, 1954. Return to text.

- Hall, G.S., Adolescence and Its Psychology, D. Appleton, New York, p. 546, 1928. Return to text.

- Doukas, D., Corporate capitalism on trial: the hearings of the Anthracite Coal Strike Commission, 1902–1903, Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power 3(3):367–398, 1997; p. 367. Return to text.

- Blake, R., Avis, W. and Mouton, J., Corporate Darwinism, Gulf Pub, Houston, 1966. Return to text.

- Olien and Olien, Ref. 35, p. 113. Return to text.

- Gelernter, D., Bill Gates, TimeMagazine 152(23):201–205, 1998; p. 202. Return to text.

- Wyllie, I.G., Social Darwinism and the businessman, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 103(5):629–635, 1956. Return to text.

- Wall, Ref. 13, p. 379. Return to text.

- Morris and Morris, Ref. 1, p. 84. Return to text.

- Wyllie, Ref. 36, pp. 83–84. Return to text.

- Larson, Ref. 21, p. 27. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.