The scars of a nation

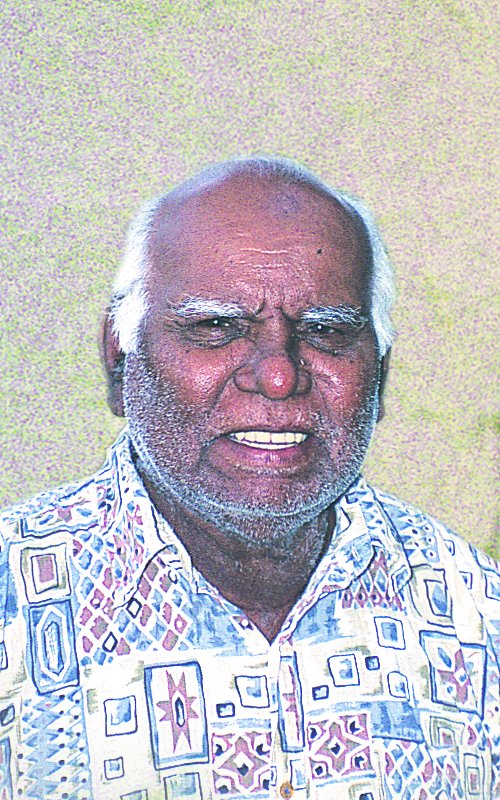

A talk with Pastor George Rosendale of far north Queensland’s Gwguyimithirr people

Talking about the past pain of one’s own people is never easy. For Australian Aboriginal Pastor George Rosendale, the tragic consequences of unbiblical ways of thinking about the history of man (in particular, evolution) have mauled several generations of his family. But there was no trace of bitterness when we spoke.

Many scholars have documented how Australia’s Aboriginal people were regarded, even before Darwin, as ‘not yet human’. But after Darwin’s Origin of Species was published, their treatment took a dramatic turn for the worse.1 For one thing, they were regarded as doomed to die out in the ‘struggle with the superior white races’. So it was widely promoted as a kindness to hasten their extinction in ‘humane’ ways.

One such way was by ‘breeding them out’. Any half-caste children were forcibly removed from Aboriginal society as a matter of policy, leading to the so-called ‘lost generation’.2 The settlement where George Rosendale lives, Hope Vale (a former mission, in the vicinity of Cooktown, several hours north of Cairns) is, he says, largely made up of this ‘stolen generation’. His grandmother was actually from another far northern tribe, the Gugu Yalanji people of the rainforest regions near Bloomfield. Pastor Rosendale said, ‘She was taken away twice from her family — the first time she was sent away with her sister but ran away and walked back to Bloomfield; then the next time they picked her up they sent her here, to Hope Vale.’

This grandmother, who was actually one of the first converts to Christianity in the region, had featured in the first conversation I ever had with Pastor George, some years earlier. We were talking about the way in which early missionaries ignored the Bible’s real history, which should have alerted them to the fact that Aborigines still recollect something of their pre-Babel-dispersion history in their stories. It would also have made it clear that all people were very closely related, since they all descended via Babel from the one group of Flood survivors, and not so long ago. Thus notions of intrinsic biological inferiority (commonly accepted, if often unconsciously, even by well-meaning missionaries) could not be right. Looking for (and finding) such relics of biblical history within indigenous culture would also have been a potent tool to reach these people with the Gospel.

Pastor George mentioned that the first time he heard of the Tower of Babel story in Sunday School, he raised his hand in indignation, saying ‘You white-fellers have it wrong, the origin of languages didn’t happen in the Middle East, that happened up here, near Cooktown. My grandmother told me our story, it’s just like that one.’ His grandmother had heard it when she was a young girl, long before their people had had contact with missionaries.

His people have a Flood story, too, which has clearly become modified to the conditions of Australia’s tropical north. He said, ‘Our story says that people were breaking the laws of our ancestor spirit (the one who created everything and gave life), which made him angry and he sent a huge cyclone which just rained and rained and gradually flooded the whole area except for the top of a hill. The few that made it there were saved; the rest were drowned or eaten by crocodiles as they tried to swim to this safe place.’

Dance of freedom

Pastor George also told of a dance performed for countless generations by his people after a funeral. One dancer has a black cockatoo feather, the other a white one. The black-feathered one also has a rainbow-coloured mock serpent attached to his heel. At the end, someone hits the serpent on the head with a stick and the serpent breaks away from the heel, at which the dancer leaps for joy. This is amazingly reminiscent of Genesis 3:15, where the ‘seed of the woman’ (the virgin-born Christ) bruises the head of the serpent (Satan). This passage has long been seen as the ‘protogospel’, prophesying Christ’s future victory over Satan and sin at the Cross, thus setting believers free.

George Rosendale says that the dance is ‘a foreshadowing of that freedom we see in John’s Gospel, where it says, “If the Son shall set you free, you shall be free indeed”. Years ago I used to call it a death ceremony, but after a while, thinking about it some more, I now call it more of a freedom ceremony.’

Discussing racism made him very sad. ‘It’s so wrong. We all come from the same thing,3 the same ancestry,’ he said. Pastor Rosendale is also aware that racism is not confined to ‘whites against blacks’, and opposes it on biblical grounds no matter where it comes from. He said that there were sometimes racial tensions between groups of Aboriginal people who live at Hope Vale, but are from different ethnic backgrounds and geographical locations.

The answer, he believes, is for people’s lives to become transformed through Christ, through believing the glorious message of the Bible. Having worked as a pastor for 30 years, and as an evangelist for 10 years prior to that, he has seen such transformation repeatedly take the place of hopelessness and despair in a traumatized and scarred people.

Pastor Rosendale’s comments brought the depth of this trauma into sharper focus. ‘There was so much genocide in this area,’ he said. ‘Out west, where the people fought against the troopers, they call the place Battle Camp. My mother’s people, men, women and children, were slaughtered and all but wiped out. They shot them out when she was eight, but she and her grandmother were able to escape. Then later on they caught Mum and sent her away. She thought that her entire family had been killed like other families, but later she found that they had not shot her really young siblings, but sent them away. Her baby sister was fostered by a white couple. I came across her, my aunty, nine years ago for the first time. It was a great reunion for us, but my mother never met her, and died wondering what happened to her.’

Other times, said Pastor George, entire families and tribes in the region were completely wiped out. ‘Mother often told us these things and they were painful stories to tell. But she would always say afterwards, “But children, I have found love and forgiveness in Christ, and I want you children to treat everyone the same, to love and to readily forgive. It was the greatest sermon I’ve ever heard in my lifetime.”

References and notes

- Darwin’s Bodysnatchers, Creation 12(3):21, 1990; Wieland, C., Darwin’s Bodysnatchers, Creation 14(2)16–18, 1992; Wieland, C., Evolutionary racism, Creation 20(4):14–16, 1998. Return to text.

- This is not to deny that there have been many cases in which, just as with white people, children were removed for their welfare. However, the policy in question has been overwhelmingly documented as systematic, and motivated by a strong belief in the intrinsic superiority of one ‘race’ over another. Return to text.

- Acts 17:26; Ham, K., Wieland, C., and Batten D., One Blood, Master Books, AZ, USA, 1999. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.