William Jennings Bryan

American tyrant … or hero?

Almost 601 years ago the Scopes ‘Monkey Bill’ trial in a backwoods Tennessee courtroom captured world headlines for weeks on end. It sparked discussion and debate in families, churches and communities throughout western nations.

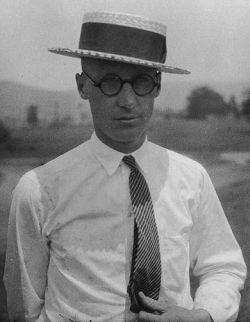

A young teacher named John Scopes (1900–1970) had been accused of teaching evolution. Leading the prosecution in the court was nationally famous, three-times presidential candidate and previous leader of the American Democratic Party William Jennings Bryan (1860–1925). Five days after the trial, Jennings Bryan was dead! By then however the Press had painted such a devastating picture of the prosecutor that many were glad to see him gone.

So who was William Jennings Bryan and why did he end such a prestigious career in this fashion?

Few Americans in the history of the United States have drawn such love, loyalty, and reverence from the masses of common people as did William Jennings Bryan. Few have had such famous enemies, but even they found him unforgettable. They saw him as a great man and grudgingly acknowledged him as being indefatigable, forgiving and large-hearted. His remarkable gift of faith in the American people to choose the good and the right was incomprehensible to them.

During his life (1860–1925) Bryan served as politician, statesman, Democratic Party Leader, Secretary of State, writer, lawyer, popular lecturer and crusader. He was vilified by the Press, feared by the administration, by plutocrats and monopolists, but loved devotedly by millions. Among the endearing titles the people gave him were ‘king’, ‘peerless leader’, ‘great commoner’, ‘shining knight’, ‘great Christian statesman’, and ‘progressive reformer’. Bryan was loved and hated, but he was never ignored!2

Born in Salem, Illinois, into a strong Christian family, his father was a staunch Baptist and a Judge of the Circuit Court, strongly pro-Southern in sentiment (and a Democrat in politics). His mother was a strong-minded Methodist who taught her son to read in his early years. In fact, she presided over the children’s education (there were six of them) until William was 10 years old.

Roots

His family’s known ancestry on his father’s side includes William De Bowbray who had helped wrest Magna Carta from England’s irascible King John in 1215; Brian Boron, ‘King of the Irish’, born about 927; and William Smith Bryan, the first Bryan known to suffer banishment to the Virginian Colony during the Puritan Revolution.

On his mother’s side his roots have been traced to thirteenth century England and linked with the Brewsters who crossed the Atlantic on the Mayflower’s first voyage in 1620.

William’s father, Silas Bryan, greatly treasured the power of knowledge. He graduated from the Methodist McKendree College, Lebanon, Illinois by working as a farmhand and woodchopper. He pursued his studies to the M.A. and became County Superintendent of schools, studied law, and was admitted to practice by the time he was 29. When he was 30, he married a previous student Mariah Jennings, (12 years his junior) whom he had taught at Walnut Hill School. Soon after his marriage, Silas became a State senator and in that role was able to follow the development of issues which ended in the Civil War. At close range he observed the split of the democracy and personally knew Abraham Lincoln, though he didn’t support him for the Senate.

The boyhood of William Jennings Bryan was rich in the influence of educated and famous people but they were people who did not lack the common touch.

As circuit judge his father was a deeply religious man who lived a serious, prayerful life believing his decisions once worked out through prayer to be totally unchangeable. William was in his most impressionable years when his father had attained the peak of his own career.

Education

It has been said of Silas that he tried to make William a replica of himself religiously, politically and in ethical principles. However, the lad’s independent spirit showed through when, at only 14, he left the Baptist and joined the Presbyterian Church. No doubt this break with his father’s beliefs involved a deep decision not to be a duplicate of his father. At the same time he never ceased to love and honour him. His respect for the aged throughout his life is revealed in the practical faithfulness he showed to his widowed mother-in-law who made a home under his roof for many years till her death.

At age 15, a shy and timid William set off for Whipple Academy to do preparatory studies for Illinois College, not knowing whether he wanted to become a minister or a lawyer/politician like his father.

He succeeded at Whipple and moved to Illinois College at Jacksonville, Illinois, graduating with his primary degree in 1881 when he was 21. Political speeches, debating and earlier church speaking had completely cured his shyness by the time he met and fell in love with Mary Baird. She became his adoring and faithful supporter and encourager. Later she was to study law in order to ‘help him’! The year before their marriage William graduated from the Union College of Law in Chicago and practised successfully in Jacksonville from 1883 to 1887. He and Mary were wed 1 October 1884. On the wedding ring he had inscribed ‘Won 1880—One 1884’.

Politics

As a Christian, William Jennings Bryan was a committed and very dedicated man. He also applied the same zeal and purpose to his membership in the Democratic Party.

His love for the common man, rural and urban, was genuine and sincere though it must be said his affinity was closer to the country people. His faith in the ordinary man’s ability to choose the right and good can only be described as extraordinary. He perceived their capacity as being hampered only by the selfishness of monopolists and plutocrats who trampled and exploited the working class. He believed it was the little man who did the hard work while the big corporations watched their profits grow. In his years as a member of Congress his zeal was that of a crusader battling holy wars. Over his long political career3 his powers of persuasion were used to achieve:

- Women’s Suffrage. His commitment to peace and prohibition intensified his fight for female suffrage and this Amendment was adopted in 1919.

- Child Labour. In 1922 his eloquence was turned to attack the Supreme Court’s overthrow of the National Child Labour Act of 1919. He despised the court decision as a victory for capitalism ‘whose greed coins the blood of little children into larger dividends’.

- Income Tax. In 1894 he spoke in favour of a Tariff Bill to provide for 2% tax on all corporate incomes and on individual incomes in excess of $4,000. It is interesting to note that this Bill became law, without the signature of the President, by being passed in both houses of Congress.

- National Bulletin. He advocated the free distribution of a National Bulletin to protect people from the power of the Press which he claimed favoured monopolists and plutocrats. The nation had a right to unbiased information.

- Prohibition. He saw this issue as Progressive Reform, a moral issue and ‘war measure’ and it was largely due to his campaigns that the 18th Amendment was adopted. He was so exhilarated by this success that he predicted a world-wide adoption of prohibition. However, he later changed his stand to one of local options.

- The Signing of 30 Separate Peace Treaties—by Great Britain, France, Spain, and China, and every other major nation except Germany, Austria, Hungary, and Japan.

William Jennings Bryan stood three times for the Presidency of the United States and three times lost. Although he never achieved the highest office in the land, it is likely that he saw more of his proposals become law than any President had done.

The Press attacks

Over many years William Jennings Bryan provided headlines for the nation’s Press by his many political, religious, and social activities. In 1896, when he was 35 years old, his ‘Cross of Gold’ speech won for him the Democratic presidential nomination and made nationwide newspapers aware of his popular acceptance and brilliant oratory. The Press not only loved his newsworthiness, they loved the way he always drew fire and made capital out of it all his life. Bryan was news with a capital ‘N’. He could be editorialised, criticised or serialised but in every case he was saleable news.

Bryan therefore decided it was necessary to publish his own paper and called it The Commoner.

Aimed at his followers, to give them the truth as he and they saw it, he published many lectures and editorials over the years. But the Press continued to pursue him to mock, criticise and vilify him. Often he was hurt, frequently he wrote his own defence, but he never showed malice. Every year he travelled thousands of miles crusading for reforms, lecturing from town to town and occasionally giving religious addresses.

Great and rapid changes were seen in the America of the 1920s. Bryan was growing older and perhaps he failed to perceive and understand what was happening.

In 1924, an election year, he declined nomination for President. His interest in religious subjects had deepened and this was becoming widely known. But in that year against his own better judgment he again allowed himself to be swept along by his love of politics and people, and he found himself a delegate at the Democratic Convention in Madison Square Garden, New York. Once more he became embroiled in the old contentions. The fighter in him could not break away. This time, though, he was not carried high on the shoulders of his admirers and applauded for long periods of time. Instead he was hissed at and in danger of being hooted, according to the writer Edward Lee Masters—a bitter reception from his beloved crowds.

But early in 1925, the future Democratic President, Franklin D. Roosevelt, sought his help in restoring unity in the Democratic Party, and the crowds cheered him again at a Brooklyn, New York, rally and drew from him a promise that he would be in politics ‘till he died’. This encouragement helped him to decide to campaign for the Senate elections.

Sadly, Bryan’s dream to spend his last days in the dignified atmosphere of the Senate chambers was never to be realised. Instead of the stately halls in Washington he was to live and fight his last battle in a small town courtroom in Tennessee with an atmosphere more like a bull ring or circus arena. The closing days of his life would see the Press cast him in the role of an ignorant fanatic and a bigot, which is how the world mostly sees him still.

Thirteen days

As his political career began suddenly and amid turmoil with a glorious reception from the common people, so his career ended suddenly, though not devoid of triumph for the ones he knew and loved so well. His decision to give himself to the cause of the fundamental Christians of America when they appealed for his help was impulsively given and without thought of personal cost.

By the spring of 1925 Bryan was living in Florida. He had moved from Lincoln, Nebraska, some years before for the sake of his wife’s health.

Florida was the first State to legislate against the teaching of evolution in schools. A few years earlier in 1922 Bryan had stated in his newspaper, The Commoner: ‘I was never more interested in politics … and never more interested in religion. There is no conflict between them.’ It was not surprising then that he should join the ranks of those voicing dismay at the teaching of evolution to their children. In fact, the surprise would have been if he had not. North Carolina and Tennessee soon took up the fight with the result that college professors and secondary school teachers who accepted the theory of evolution resigned. Throughout the South and Mid-West States, local school boards clearly expected that their teaching staff would ignore the new biological theories in the textbooks.

In his advice on the drafting of legislation regarding evolution in Tennessee, Bryan cautioned against their inclusion of fines ‘from $100 to $500’ but, in spite of his warning, the Bill included that clause when it was passed early in 1925. It banned the teaching of the theory of evolution in Tennessee’s classrooms. In his congratulatory telegram to the governor, Bryan stated, ‘the South is now leading the nation in the defence of Bible Christianity. Other States north and south will follow the example of Tennessee’.

The ACLU

It was at this point, or soon afterwards, that the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) stepped into the arena. History records that the one attempt to enforce the Tennessee ‘Monkey Bill’, as it has been called, was not due to the actions of its friends but its foes, for not long after the Bill became law the ACLU made the decision to sponsor a test case.

It was late in April 1925 when their search for a plaintiff began. Tennessee newspapers were informed of the willingness on the part of the American Civil Liberties Union to guarantee legal and financial assistance to any teacher who would test this new anti-evolution law. George Washington Rappleyea (1894–1966), a young mining engineer in Dayton, Tennessee, who had opposed the law, read the ACLU’s offer. He decided that Dayton, Tennessee, was just the place to test the law and challenged John Thomas Scopes, the town’s 24-year-old science teacher. When he asked Scopes whether he could teach biology without teaching evolution he got the negative reply he desired.

The head of the local County Board of Education was F.E. Robinson who also owned the town’s drugstore, and it was there that the historic conversation took place.

Robinson, who overheard the exchange between teacher Scopes and Rappleyea, promptly reminded young Scopes that he was violating the new law. ‘So has every teacher’, Scopes replied. He then explained to Robinson and Rappleyea that the State-approved textbook, Hunter’s Civic Biology taught from the evolutionary standpoint. Almost casually, Rappleyea suggested that they should take the matter to court and test its legality. The engineer Rappleyea, a very articulate young man, then persuaded Scopes to cast any reluctance aside.

He appealed to him on the grounds of his American citizenship and his duty as an educator and so gained his consent to the arrest and trial.

So the nefarious plans were laid. ‘I wired the ACLU’ Rappleyea has since recorded, ‘that the stage was set and that if they could defray the expenses of production the play could open at once.’ They agreed and the engagement of the principal actors followed. On May 7, Scopes was arrested. On May 12 Bryan, who was visiting Pittsburgh for a series of lectures, received word from the World’s Christian Fundamentals Association of his selection to be their attorney. He wired back that he accepted without compensation on condition that the State’s Law Department agreed. A few days later he read another request from one of the State’s prosecuting attorneys, (Mr) Sue Kerr Hicks (1895–1980), that indeed he should be associated with them in the trial.

About the same time Clarence Darrow (1857–1938) and Dudley Field Malone (1882–1950) offered their services to John Randolph Neal Jr. (1876–1959), Scopes’ local attorney.

Scopes and Neal accepted their offer and the ACLU found itself with an outspoken skeptic instead of the politically conservative and orthodox religious attorneys they had at first envisaged. Bryan’s son, William Jennings Bryan Jr., then a Los Angeles attorney and deeply desirous of a place in the fundamental Christian crusade, took his place beside his father.

The two Bryans for the State versus Darrow, Malone, and the ACLU’s attorney Arthur Garfield Hays (1881–1954) for the defence, provided a free-for-all kind of situation.

It was an atmosphere in which the true issues involved were in danger of being confused or lost. From the very outset Bryan perceived what the case was about. ‘It is the easiest case to explain I have ever found’, he said. ‘While I am perfectly willing to go into the question of evolution, I am not sure that it is involved. The right of the people speaking through the legislature, to control the schools, which they create and support is the real issue as I see it.’

He posed that the first question was ‘Who shall control the schools?’ and discounted the scientists as being in control as they were one in 10,000 of the people.

Moreover, the teachers had been employed to take directions. Yet, at the same time, he could see that the case was a duel to the death between Biblical Christianity and evolution. He feared his beloved American people could not perceive what a menace the theory of evolution was. Henry Fairfield Osborn (1857–1935), a scientific ally of the defence, observed before the trial, ‘The facts in this great case are that William Jennings Bryan is the man on trial; John Thomas Scopes is not the man on trial. If the case is properly set before the jury, Scopes will be the real plaintiff, Bryan the real defendant.’

As Darrow wrote later this was the courtroom strategy, a strategy designed to focus attention on Bryan and all the other fundamentalists in America.

The ACLU lawyer Hays portrayed it as a battle between two types of mind, ‘The rigid, orthodox, accepting, unyielding, narrow conventional mind and the broad, liberal, critical, cynical, skeptical and tolerant mind.’ During the trial a new question raised itself in Bryan’s mind which began to modify his earlier stand on religion and the schools: If the spiritual foundations of the nation were threatened by the theory of evolution, were these foundations also endangered by the absence of any religious teaching in the schools?

Years earlier, Bryan had suggested to his friends Rabbi Wise and Cardinal Gibbons that ‘there should be some way of utilizing part of the school time in the teaching of morals and believing that morals rest upon religion, I have no way of teaching them except under religious supervision.’

Apparently at his prodding, Florida legislature again took the lead and passed a law providing for the reading of Scripture in public schools. This was good but Bryan wanted more … ‘the reading of the Bible is not sufficient. The Bible has to be taught as school lessons are taught, by teachers who are free to interpret, explain and illustrate them.’ He advocated the religious development of young Jews and Catholics, as well as that of Protestants, by providing school room on equal terms for religious teaching.

During the Scopes’ trial, the Press’s attitude was so hostile to Bryan that a New York Times correspondent blatantly informed his readers that Bryan was ‘planning to “put God in the Constitution”,’ an aspersion Bryan very quickly denied. When the well-known anti-Christian journalist Henry Louis (‘H.L.’) Mencken (1880–1956) arrived in the little town of Dayton in the Tennessee hills country, along with throngs of other newsmen and onlookers, he exclaimed, ‘The thing is genuinely fabulous. I have stored up enough material … (for) … 20 years.’

There was something gloriously exhilarating for Bryan in the opening days of the trial. He spoke first to the Dayton Progressive Club then later at a gathering assembled at the Morgan Springs Hotel, followed by another speech to hundreds waiting outside.

The Methodist Episcopal pulpit provided another opportunity and he spoke individually to journalists with a gentle friendliness which ‘surprised’ them, but in no way disarmed them! A New York Times correspondent was convinced he was ‘more than a great politician, more than a lawyer in a trial, more even than one of our greatest orators, he is a symbol of their (the people’s) simple religious faith.’

And what was the outcome of this famous ‘stage play’?

At the end of the trial that lasted 13 days, the anti-evolution statute enacted by the Tennessee state legislature was incontestably upheld. In spite of a resounding legal victory, in the battle fought in the courtroom, the war with the Press had been lost before it had been started. The machinations of the media moguls had heaped only ignominy and castigation on Bryan and his supporters. H.L. Mencken and others had portrayed the fundamentalists (epitomized by Bryan) as country yokels, uneducated, thoroughly uncivilized and probably laced with hookworms. Evolution may have been declared outside the law by the court, but the Press and the ACLU had declared creation outside of the classroom, outside of commonsense and anti-science and they have sought to enforce their decision ever since!

Journey’s end

The trial ended 21 July 1925. Suddenly on 25 July, William Jennings Bryan was dead, of diabetes mellitus, ‘the immediate cause being the fatigue incident to the heat and his extraordinary exertions due to the Scopes Trial’. One of the world’s greatest crusaders lay silent, but he had not been defeated. He had not been broken by the trial.

The beloved ‘Commoner King’ had little time to become aware he was the most vilified man in America. In those five days before his death his hours were crowded. He dictated a speech and arranged for its publication. He travelled. He proofread. He laid plans for a family vacation—hardly occupations of a broken and exhausted man. It is significant that his last public speech was a morning prayer offered in church on the day he died. During an afternoon nap he peacefully passed into the presence of his Creator and Lord.4

Postscript

Despite the widespread opinion that the Scopes trial pushed creation out of the classroom and opened the door to evolution, history has revealed that it was not so.

The media may have won a popular opinion battle against the fundamentalists, but the results of the Scopes trial in the classroom were the downgrading of evolution in most textbooks from 1925 on and the fact that evolution almost ceased to be taught in pre-college biology courses for the next 35 years. In fact it was the introduction of the atheistic Biological Series Curriculum Studies (BSCS) textbook The Web of Life with its strong emphasis on evolution which reopened the battle.

In 1963 the state of Arkansas still had anti-evolution laws on its statutes to prohibit the teaching of evolution. (Why are there Creationists? by J.A. Moore, Journal Geol. Ed., 1983, vol 31, p. 95.)

What the Scopes trial did produce was an agnosticism towards the topic of creation amongst Christians. They licked their wounds for such a long time and felt it was safe to regard creation as true, but an unimportant side issue. In the public schools, little stand was taken on creation and so a void was produced with regards to origins in high schools that BSCS would ultimately fill: most Christian parents throughout the western world with children in high school today were not directly taught evolution in high school. They were not taught about creation either. Hence when they react against the teaching of evolution in public institutions and establish Christian schools for their children, they reject evolution, but put nothing in its place. They educate their children the way they were educated regarding origins—agnostically. They could make no greater mistake.

Such Christian schools with an agnostic policy to literal six-day creation will in the end go the same way as public schools—overt humanism. The exercise will have been an entire waste of time.

References and notes

- It is now almost 90 years since the trial, but this article was first published 30 years ago. Return to text.

- Colelta, P.E., William Jennings Bryan, Political Evangelist, 1860–1908, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln. 1964. Return to text.

- Glad, P.W., The Trumpet Sounded, William Jennings Bryan, and His Democracy, 1896–1912, University of Nebraska Press. 1960. Return to text.

- Levine, L.W., Defender of the Faith. William Jennings Bryan, 1915–1925, by Oxford University Press, New York. 1965. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.