Australia’s remarkable Red Centre

Come visit Australia’s Red Centre. See how the spectacular scenery was formed during the recent global catastrophe of Noah’s Flood. Check the short film clips that feature some of the popular Red-Centre sites.

Contents

Australia’s Red Centre is popular with tourists the world over, eager to visit and experience the fascinating desert environment. The population of the centre is small, with isolated communities dotted over the countryside. The only town of any size is Alice Springs.

Oxidized iron gives the area its distinctive reddish hue. Because vegetation is sparse, the rocks are easily visible to tourists, such as the strata in the MacDonnell Ranges, which run for hundreds of kilometres across the Red Centre. These geological features of central Australia reveal compelling evidence of the global Flood catastrophe of Noah’s day.

1. The geology of central Australia

Older rocks

In simple terms, the rocks in the area can be divided into two groups according to age. First, the older rocks, composed of metamorphic and granitic rocks, form the basement and have been described as ‘blocks’. They have been folded, faulted, sheared, and metamorphosed. Uniformitarian geologists say these formed over a period from 1700 to 900 million years ago (around the middle Proterozoic of the Precambrian). Of course, rocks do not come with labels on them stating their age. Uniformitarian geologists1 assign an age by considering a smorgasbord of criteria, but with the overriding goal of fitting the rocks into the long-age evolutionary philosophy. In particular, this philosophy is based on an old, untested commitment by the mainstream geological fraternity to the idea that Noah’s Flood never happened. However, there is abundant evidence that it did, and that the million-year ages assigned are far too long. (For more information see How dating methods work and related articles.)

From my investigation of the geology of Australia, it seems that these older rocks formed early during the year-long global Flood as the crust of the earth was breaking apart as that catastrophe was initiated, some 4,500 years ago.2,3 Some biblical geologists would assign these rocks to the momentous events of Creation Week, about 1,700 years before the Flood.4 However, I think there are geologic features that are not consistent with that view, such as volcanic eruptions happening during Creation Week.5

Younger Rocks

The second group of rocks is the younger rocks, which are mainly of sedimentary origin. They are described as being deposited in sedimentary ‘basins’ on top of the basement rocks. They too have been folded, faulted, sheared, and metamorphosed, but not as intensely as the basement rocks. Based on their philosophical assumptions, uniformitarian geologists say these were deposited over a period from 900 to 300 million years ago (late Proterozoic to Devonian). However, most biblical geologists would consider that these sedimentary rocks were deposited early during the global Flood.3

It is important to note that the sediments that filled these sedimentary basins of Central Australia were not the final sediments deposited by Noah’s Flood. A large proportion of Eastern Australia is covered by later sediments deposited as the floodwater was rising towards its peak on the earth. Some widely distributed sediments are those that contain the underground water of the Great Artesian Basin, which cover a large portion of Queensland and New South Wales, as well as parts of the Northern Territory and South Australia. The article The geological history of the Brisbane and Ipswich areas, Australia explains the classification of these sediments. The important point is that these later sediments were eroded from central Australia, revealing the earlier rocks underneath.

Erosion

We have noted that movements of the earth’s crust folded, faulted, sheared, and metamorphosed the rocks. This would have occurred during the cataclysmic crustal movements during the first part of the Flood, as the thick pile of rocks was being deposited. In fact, the area has been so severely disturbed that the geological structure is complex and difficult to unravel.

These rocks also experienced enormous erosion, with vast quantities of material being removed at various times in the area’s geological history. This erosion would have occurred as the catastrophic water-driven geological processes unfolded. The final episode of erosion would have occurred as the waters of Noah’s Flood receded from the Australian continent into the surrounding oceans.

As a consequence of these earth movements and erosion, different rocks have been exposed at the surface in different locations. This is illustrated in the simplified geological maps of central Australia.

Geological maps and cross section

A simplified geological map showing the structures in central Australia is presented in figure 1. Two of the older basement blocks (Musgrave and Arunta) are shown as well as four of the later sedimentary basins (Officer, Amadeus, Ngalia and Georgina). Picture in your mind that the basins sit on top of the blocks. The Amadeus Basin is 850 kilometres long from east to west, and 250 kilometres wide.

In figure 2 the later sediments of the great Artesian Basin have been added to the simplified geological map. These sediments were deposited after the sedimentary basins in central Australia and almost certainly on top of them. They have subsequently been eroded away from central Australia. Picture in your mind that the yellow sediments once sat on top of the basins and the blocks. Uniformitarian geologists have assigned these sediments to the Mesozoic (250 to 66 million years ago within their dating philosophy) but biblical geologists would place them about mid-way through Noah’s Flood as the floodwaters were rising towards their peak on the earth. The timing of these sediments is set out in the article The Great Artesian Basin.)

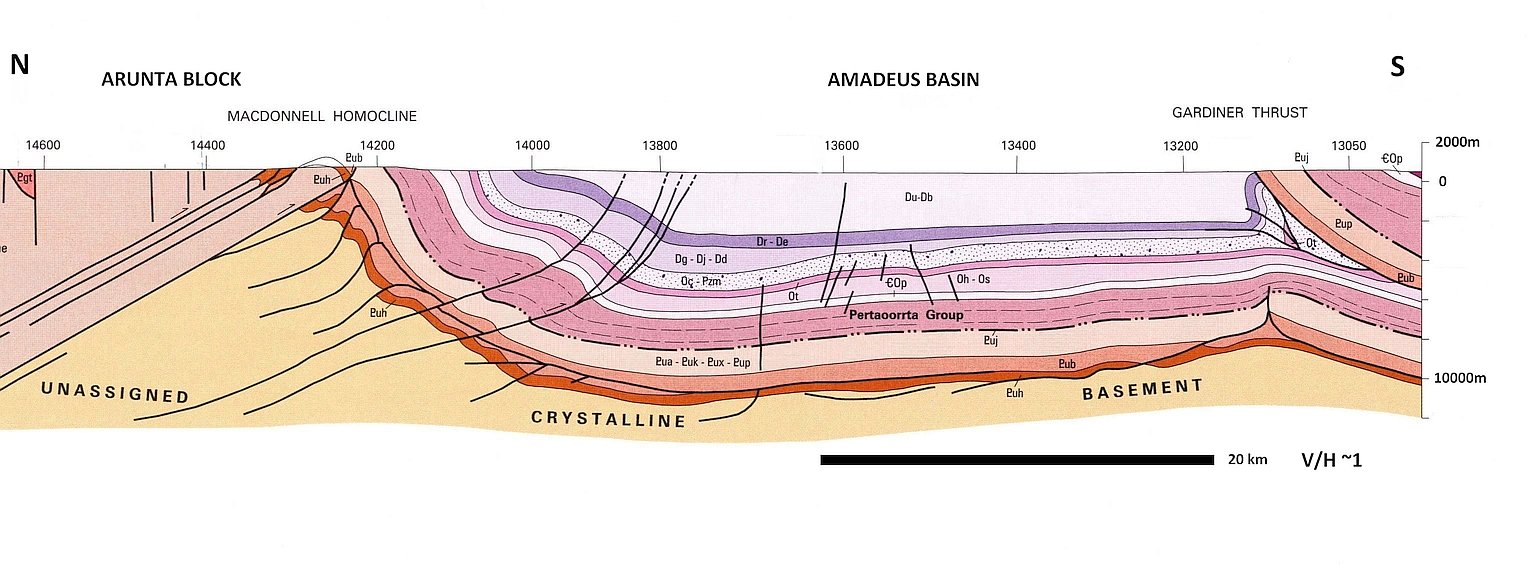

Figure 3 shows a geological cross-section through a portion of the Amadeus Basin along a north-south line located some 165 km west of Alice Springs. The section spans about 25% of the basin. You can see in the figure that the basin extends some 10 km below the surface.

Although the individual layers of sediments in the basin are clearly distinguished, it is clear that the sediments have been pushed by enormous forces. This has caused the whole pile of sediments to curve upwards to the north (left) of the basin at the edge of the Arunta Block. Here the sedimentary strata have been cut off at ground level, which means that an enormous quantity of rock material has been eroded away. This is the area where the MacDonnell Ranges run across the surface (perpendicular to the section).

This pushing or compressing of the sediments in the basin is also evident to the south (right) of the section. Here, once again, the whole sedimentary pile curves upwards to the north and has been thrust on top of the sediments underneath. These upward facing sedimentary layers have again been cut off at ground level and all the overlying material has been carried away. These enormous crustal movements took place in the first part of Noah’s Flood.

Let’s now look at some of the well-known tourist destinations in the area.

2. Alice Springs

Alice Springs sits at the southern edge of the Arunta Block next to the Amadeus Basin. It is toward the east of the basin as shown in figure 4. Looking north from the Anzac Hill Lookout in the city you can view the low, rolling landscape of the granite country. This is the southern edge of the Arunta Block. The actual contact between the two is visible in Heavitree Gap to the south of Alice Springs.

On the other side of the town, to the south, the prominent Heavitree Range runs across the landscape like a long, high wall (figure 5). It is part of the MacDonnell Ranges, which extend for hundreds of kilometres east-west across the Red Centre. These ranges run along the northern edge of the Amadeus Basin.

It is hard to imagine, as we stand at the Anzac Hill Lookout, that thousands of metres of thickness of rock have been removed from above. However, the geological evidence, as presented on geological maps, is clear on that (figure 3). We are standing in an area that was once deep inside the earth. And at this point we can see in the rocks evidence of the enormous forces that convulsed the crust during Noah’s Flood.

Because of these earth movements the rocks have been sheared, folded, faulted and metamorphosed. As previously discussed, the basement rocks formed very early in Noah’s Flood as the crust of the earth was breaking open. They provide the foundation on which the younger sedimentary rocks were deposited later in the Flood.

The metamorphic rocks in the area, which can be seen at Anzac Hill Lookout, include gneiss, which has bands of dark and light minerals. The bands formed when the rock was sheared by metamorphic forces. Also in the area are igneous rocks, such as light-coloured granite and dark-coloured dolerite, both of which crystallize from molten magma. Outcrops of a coarse-grained granitic rock called pegmatite, which is a late stage of crystallization after most of the granitic magma had already crystallized, are also found there. Some excellent crystals of the mineral mica, characterized by transparent sheets, can be found in granite and pegmatite outcrops at Anzac Hill.

Granite formation

It was once thought that granite originated deep under the earth as a towering molten ‘blob’ of liquid magma kilometres across. Slowly, over millions of years, the story went, the ‘blob’ of magma inched its way through solid rock for tens of kilometres until it neared the surface. This obviously would have needed vast amounts of time (and is widely regarded now as being physically impossible). Modern research has shown those ideas were wrong. Now it is considered that the molten granitic magma rushes up through long, narrow fissures in the crust—fissures just metres wide. It makes the journey within hours and days, and collects in large, underground pools near the surface. As water (volatiles) from within the magma boils off, the granite crystallizes and cools. Even large crystals are now known to form quickly, within hours and days. (See the article Granite formation: catastrophic in its suddenness.) The generation and emplacement of granites is related to the cataclysmic movements in the earth during Noah’s Flood. These movements produced the enormous volumes of granitic magma and squeezed it towards the surface through the cracks and fissures that the movements formed.

Water gap

The Todd River runs south through Alice Springs, but it rarely flows. Its bed is sandy due to lack of rainfall. However, remarkably, its course continues straight through the range, through Heavitree Gap, immediately south of the town (figure 5). This is called a water gap. Why didn’t the river go around the solid ridge? How did such a feeble river cut through a range like this? It didn’t. Something in the past cut this gap, something not happening today. That something was Noah’s Flood. Water gaps are a tell-tale signature of Noah’s Flood. Floodwaters once sat kilometres deep over central Australia. When they eventually flowed back into the ocean in the second part of the Flood, they cut this gap, and multitudes of others. There are hundreds of water gaps throughout Central Australia, some of which are featured later in this article. There are many more water gaps on other continents across the world. (The article Do rivers erode through mountains? explains how water gaps formed during Noah’s Flood.)

As our understanding of the remarkable geological features of Central Australia grows, we find they reveal compelling evidence of the global Flood catastrophe of Noah’s day. It was an enormous cataclysm that impacted the whole earth.

3. MacDonnell Ranges

The MacDonnell Ranges are a series of ridges running 650 kilometres across Central Australia. They are composed of sedimentary rock strata that have been tipped on their end. You can see in the geological cross-section (figure 3) how the strata have been tipped up and cut off at the northern edge of the Amadeus Basin. It is interesting to think that as you travel kilometres across the ridges from north to south, you are moving up the sequence from deepest to shallowest.

These sediments were laid down early in Noah’s Flood as the initial floodwaters spread abundant sediment over an enormous area. (The article The Sedimentary Heavitree Quartzite, Central Australia, was deposited early in Noah’s Flood reveals something of the evidence for that enormous energy and the geographical area that was affected.) The water level of the Flood rose continually until a depth of 10 km of sediment (as indicated on figure 3) was deposited. Then earth movements pushed the whole pile of sediment, tipping parts of it on end, other parts on top of each other, and metamorphosed the rocks. And finally, titanic volumes of rock material were eroded away leaving the strata protruding vertically out of the landscape, forming the MacDonnell Ranges.

When you look at the MacDonnell Ranges you can see that the sedimentary strata, which now form the ridges, run in straight, parallel lines (figure 6). In other words, this is evidence that the sediments were deposited in layers of uniform thickness that extended over an enormous geographical area. They were spread like thin blankets across thousands of kilometres of the countryside. This means that the processes that were depositing the sediments were highly energetic. (See the article Sedimentary blankets: Visual evidence for vast continental flooding.)

Also, you can see that the contact between one sedimentary bed and the next is straight and flat. This means that there was no erosion in the underlying bed before the next bed was deposited on top, as would have been the case if the bed had been sitting for a long period of time before the overlying bed was deposited. If there had been erosion of the surface of the underlying bed the contact would have been uneven and irregular, like the present-day surface we can observe on the landscape in the area. In other words, the straight contact between strata means that not much time elapsed between the deposition of one bed of sediment and the next. (The article ‘Flat gaps’ in sedimentary rock layers challenge long geologic ages explains this evidence in more detail and its significance, using examples from the Grand Canyon, USA.)

4. Ormiston Gorge

Ormiston Gorge is a beautiful site some 135 km west of Alice Springs, featuring a permanent waterhole with a sandy beach. The gorge cuts through a high ridge in the MacDonnell Ranges (figure 7). The steep cliffs open a window onto the spectacular geology in the Red Centre.

Thick strata exposed in the gorge are part of a geologic formation widespread through Central Australia, a formation geologists call the Heavitree Quartzite. Composed originally of quartz sandstone, the sediment was converted to hard, blocky quartzite by huge volumes of silica (quartz) cement connected to enormous earth movements that compressed, metamorphosed, folded, and fractured the rocks.

The thickness of the beds and the vast area they cover indicate that the sediments were laid down by an enormous volume of water flowing with high-energy across the area. These sediments are tangible evidence of the global cataclysm we know as Noah’s Flood. They would have been deposited early in that catastrophe, during the initial high-energy phase, as the floodwaters were bursting across the earth and beginning to rise upon it. (See the article on Heavitree Quartzite.)

Uniformitarian geologists say the rocks are some 800 million years old, but as we have mentioned, rocks do not have labels with dates on them. These geologists decide those vast ages by assuming Noah’s Flood never happened, and that the sediment was deposited slowly and gradually. However, other geologists consider that, rather than being deposited by a tiny bit of water over a vast time, these rocks were deposited by a vast amount of water over a short time, during Noah’s Flood.

As the floodwaters rose and rose, sheets of sediment were stacked one upon the other like gigantic pancakes over an enormous area. The Flood continued, and movements in the earth’s crust pushed the layers of rock across the earth, bending, sliding, and cracking them, a feature visible in the geological map of the area (figure 8). In the cliffs at Ormiston Gorge, the rocks in the top half were thrust some 2 kilometres from the north to their current location on top of the rocks in the lower half. The zone between them is called a thrust zone. These are common through the region.

The creek enters Ormiston Gorge flowing west and changes direction in the gorge to the south. Its western escarpment rises 300 m, indicating how much of the range has been eroded away. This deep gorge, cutting across the tall rocky ridge, is a water gap that cuts through the MacDonnell Ranges. As previously mentioned, there are many water gaps in Central Australia, carved as the waters of Noah’s Flood were retreating from the continent. When Ormiston Creek flows today it uses the water course carved at that time.

The orange and red quartzite rock in Ormiston Gorge is fractured, allowing large, hard boulders to break free from the wall and fall onto the floor below, forming an apron of debris. Although there are many boulders lying around, their number is not great when compared with the size of the gorge. The size of the apron is small by comparison. This lack of debris, or talus as it is called, indicates that the gorge walls were carved recently, and that erosion has not been going on for millions of years. Otherwise the gorge would be piled full of boulders. The absence of abundant debris is consistent with the timing of Noah’s Flood, which ended about 4,500 years ago.

As well as revealing the spectacular geology of the Red Centre of Australia, beautiful Ormiston Gorge displays something of the catastrophic earth-changing forces that engulfed the area during Noah’s Flood.

5. Glen Helen Gorge

Some 130 km west of Alice Springs, the Glen Helen Homestead provides a convenient stop for tourists exploring the Red Centre. Established as a cattle station over a century ago, the homestead offers motel rooms, camping facilities, and stockman accommodation.

The homestead sits alongside a towering sandstone ridge that forms part of the Western MacDonnell Ranges. It also sits on the banks of the Finke River, which, surprisingly, flows straight through the sandstone wall, forming Glen Helen Gorge, another example of a water gap (figure 9).

Because the Finke River flows through the gorge, people imagine that the river cut the gorge. But how could it? It only flows occasionally because the country is dry. Most of the time there are just a few waterholes along its length, including the one at Glen Helen. Surely, if the river had carved the landscape slowly over eons of time it would now flow around the barrier instead of through it. In other words, the gorge had to be cut first by something we don’t see happening today. That something was Noah’s Flood.

The account of Noah’s Flood in the Bible says the water rose continually until it covered every high mountain. How is that possible? Imagine if we were to smooth out the surface of the earth, pushing the ocean basins up and the continents down, until the earth was a perfect sphere. There is enough water on the surface of the earth today to cover the globe to a depth of nearly 3 kilometres.

So, continental Australia, including the MacDonnell Ranges, was covered with water during Noah’s Flood. As you travel the Red Centre, it’s interesting to picture deep water all over the landscape.

After the Flood peaked, the ocean basins began to sink and the continents rose. The water started draining into the oceans. In central Australia, it would have flowed south across the MacDonnell Ranges. As the water drained, some parts of the ranges would have emerged above the surface. Then the water would have been confined to the lower parts of the ridges, eroding them lower. Gradually, the water would have been forced into narrower and narrower channels, carving downwards, leaving a gorge through the ridge—a water gap. Along its course the Finke River flows through many water gaps, but it did not carve them. See the article Do rivers erode through mountains? for more about water gaps.

In the gorge at the base of the cliff there are a few large boulders lying around. The hard, quartz sandstone forming the ridge is heavily fractured, allowing blocks to fall out occasionally. However, compared with the width of the gorge, the number of boulders at the foot of the cliffs is small. If the cliffs were millions of years old there should be heaps of boulders in the gap. The absence of boulder debris indicates the cliffs are young, confirming the water gap was eroded recently, by receding Flood waters.

Glen Helen Gorge is one of scores of water gaps that run across the MacDonnell Ranges (figure 10). Many have become popular tourist destinations, such as Ormiston Gorge, Standley Chasm, Simpsons Gap, Emily Gap, and Jessie Gap. These provide amazing insights into the impact of Noah’s Flood on Australia. (For more information see: Glen Helen Gorge, Australia: How did it form?)

6. Honeymoon Gap

Honeymoon Gap, not far from Alice Springs, is another example of a water gap that passes through a low ridge in the MacDonnell Ranges.

Sedimentary strata are visible in the end of the ridge (figure 11). They indicate the sediment was deposited from fast-flowing water, and this was early during Noah’s Flood. The sediments cover a large geographical extent. Cross beds in the strata, visible in other outcrops, provide clues to the depth of the water, its velocity, and flow direction.

The strata are sloped at an angle because they were pushed around after they were deposited. This also occurred early in the Flood. The strata once extended far above the present land surface before being eroded away. They still extend underground. Honeymoon Gap is located at the northern side of the Amadeus Basin where the sediments have been bent upwards against the Arunta Block, as discussed in Section 1 under the subheading “Geological cross section”.

Honeymoon Gap, as with the myriad of other gaps in the Red Centre, was carved, not by the river that flows through it now but, in the second half of Noah’s Flood, as the flood waters were receding. Honeymoon Gap gives a dramatic insight of how Noah’s Flood unfolded on the earth.

7. Conclusion

The landscapes of Central Australia are astounding in their colour and appearance. They provide a dramatic picture of the reality of Noah’s Flood. Once we can envisage how that global catastrophe unfolded on the earth, and understand something of its enormous magnitude, and what to look for, we can see the evidence everywhere.

The big issue that throws people off the trail is the million-year dates that are quoted for the different geological features people visit. However, not one of the geological features came with a label attached stating the date it was formed. All such dates have been invented by people who did not see it form, and are simply stating their personal beliefs about what happened. The dates are based on their assumption that Noah’s Flood never occurred—that continental-wide catastrophes never happened. But the cataclysm of Noah’s Flood washes away the millions of years. And, the evidence for continental catastrophe in central Australia is amazing. When we consider the evidence with the Flood in mind it gives amazing insights.

So, we need to consider the evidence that is actually observed, using tools such as Google Earth and information reported in the geological literature. Then we can interpret the geology without being prejudiced by the uniformitarian belief system. When we do, we can see the unmistakable signs of enormous watery catastrophe, which are entirely consistent with the record of Noah’s Flood in the book of Genesis.

On your next visit to central Australia, you will see that the features of the Red Centre match the expectations from Noah’s Flood. Understanding Noah’s Flood changes how you look at the world, and how you see your place in it.

Summary of some Red-Centre evidence of Noah’s Flood catastrophe

- Granites: They point to rapid crustal movements generating a large magma volume, rapid magma transport through fissures, and rapid magma accumulation in plutons.

- Sediments:

- They cover a large geographical area, pointing to enormous watery catastrophe.

- Strata have a uniform size over a large geographic area, pointing to huge watery catastrophe.

- Straight contacts between strata indicate minimal time elapsed between deposition of one layer and the next.

- Thick strata point to abundant water over the area—a large-scale watery catastrophe.

- Thick strata also point to abundant sediment supply—rapid erosion and transport.

- Large cross beds in strata indicate water currents were reasonably deep.

- Recumbent cross beds in strata point to highly energetic, strong water flow.

- Hard sandstone: Quartz cement (silica) in sediment point to high mineral content in water due to the effects of Flood processes.

- Water-transported boulder deposits point to high energy water flows.

- Landscape eroded with flat planation surfaces point to erosion when whole continent was covered by water.

- Water gaps through ranges point to Flood run-off and erosion as the receding waters reduced in their level as they drained the continent.

- Small amounts of debris at the base of steep cliffs and gorges indicate the erosion occurred relatively recently.

- Eroded material taken out of the area point to the power and volume of water that flowed over the area as the floodwaters receded.

Re-featured on homepage: 25 May 2021

References and notes

- Uniformitarian geologists seek to explain what happened in the past geologically using processes that we see happening today (such as rainfall, erosion, sand on beaches). They deliberately deny that the global Flood of Noah’s day happened, and thus they invoke long periods of time to explain things. Because the past cannot be observed, it is an arbitrary philosophy, not empirical science. Return to text.

- Oard, M.J., Raindrop imprints and the location of the pre-Flood/Flood boundary, Journal of Creation 27(2):7–8, 2013. Return to text.

- Hunter, M.J., The pre-Flood/Flood boundary at the base of the earth’s transition zone, Journal of Creation 14(1):60–74, 2000. Return to text.

- Dickens, H., and Snelling, A.A., Precambrian geology and the Bible: a harmony, Journal of Creation 22(1):65–72, 2008. Return to text.

- Walker, T., Controversial claim for earliest life on Earth, Journal of Creation 21(1):11–13, 2007. See subsequent letter Volcanoes during Creation Week by Raul Esperante and reply; Journal of Creation 22(1):50–52, 2008. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.