Medieval artists saw extinct reptiles: more evidence

Seven years after it was first published, Vance Nelson’s 2011 book Dire Dragons still contains the highest quality examples of ancient artistic depictions of dinosaurs and other extinct reptiles.1 New images included in the 2018 revision add an unforeseen argument for the coexistence of extinct reptiles and man.

Is it authentic?

Two unique features make Dire Dragons stand apart from similar efforts. First, author Nelson restricted examples to include only those with no reasonable doubt about authenticity or clarity. Authenticity asks if the artifact is genuinely old rather than a modern forgery, and clarity asks if the depiction identifies a specific animal known from fossils, as opposed to a generalized and thus more easily refuted form. Stated negatively, the book eschews artwork with even a whiff of doubt about its authenticity or clarity.

The Black Wash ‘non-dragon’

The maybe-a-pterosaur image in Utah’s Black Wash illustrates this. As soon as doubts arose in 2011 about its authenticity, it was struck from Dire Dragons. Then in 2015, anthropologists used a new imaging technique to detect three authentic, ancient, and red pictographs, mostly of human forms. A vandal had outlined the original forms with chalk only recently (probably in the early 20th century), and this chalk outline has been taken as a dragon-ish form.2 Mainstream news outlets used the 2015 report as an opportunity to bash creationists who had been using the Black Wash dragon as proof that men and supposedly long-extinct reptiles coexisted—and of course to bash creation thinking in general.3

Some creation-based resources did use Black Wash as creation evidence, but Dire Dragons does not. Thus, the pterosaur debunking actually agreed with the best creation-based resource on this subject.

Does it match?

A second unique feature of the book is the insistence that depictions of extinct creatures be identified to the genus level based on body forms known from fossils. Dire Dragons tested each ancient depiction’s degree of likeness to a fossil, first by comparing its features with an existing modern reconstruction of an already-known fossil.

Nelson’s screening process added objectivity by then having an evolutionist artist (i.e., a hostile witness) again render each animal based on its bones alone. The secular artist had no knowledge of the ancient dragon-looking artifact in question. The book showcases the best matches between artifact and animal from around the world. Its pages show the ancient art right next to the evolutionist-rendered art so readers can see for themselves if the animals are dead-ringers. It makes a strong case for the authenticity of these ancient pieces of art and sets a high standard for similar studies. Now, the third edition (2018) applies these features to new ancient images to reveal a new argument for human-dinosaur coexistence.

The many dragons of St. George

Scores of ancient art pieces—whether carved, moulded, painted, or illuminated— use generic dragon forms to depict St. George’s legendary dragon slaying. Most retain too few anatomical specifications to identify them with known fossil genera. Instead, they typically take forms of a generalized sauropod, theropod, ceratopsian, or prosauropod. For example, though made more recently than medieval times, the dragon shown beneath St. George’s sword in Fig. 2 could pass for a prosauropod, but not for any specific one.

However, a handful of St. George art did match known fossils. But even in these cases the artists from different regions rendered the dragon from the same scene with different but specific anatomies. What was going on?

Perhaps each ancient artist showed a different-looking dragon for the same dragon-slaying event because they were making them up? A closer look, however, shows that although these dragons look different, each one matches a particular genus of extinct reptile. And not all were dinosaurs; some were (non-dinosaur) extinct Permian reptiles.4

Stunning similarities between the ancient art and digital remakes of the matching fossil forms include tooth shape, position, and orientation, body proportions and sizes, head shapes, and other features.

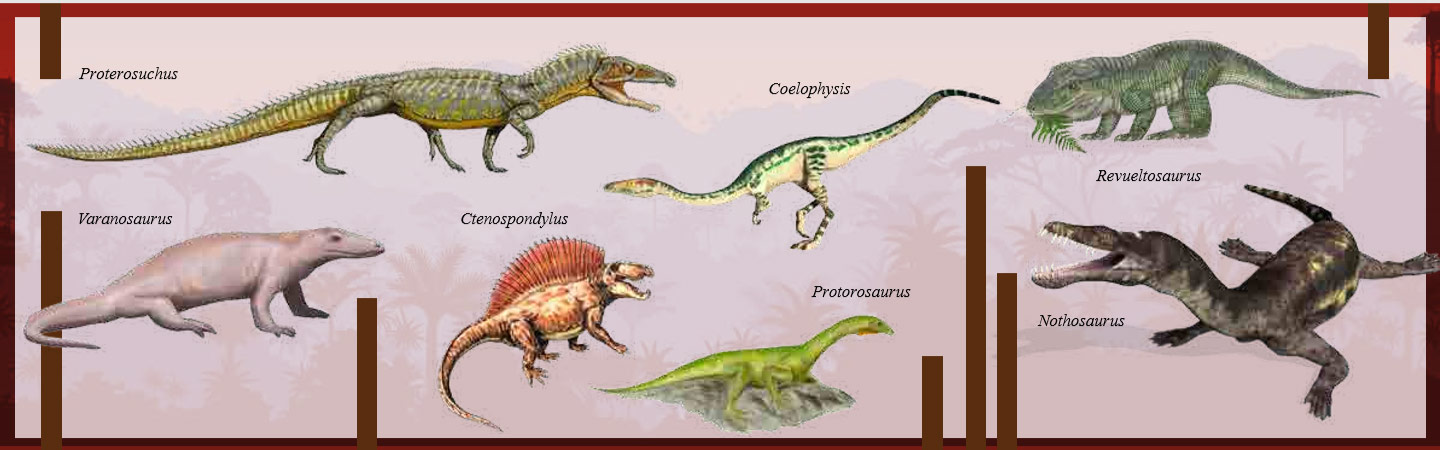

Dire Dragons identifies a Proterosuchus (Triassic) and Varanosaurus (Permian) in Belgium, another Proterosuchus, Ctenospondylus (Permian), and Revueltosaurus (Triassic) in Germany, a spectacular Nothosaurus (Triassic) in Spain, a Protorosaurus (Permian) in France, and a Coelophysis (Jurassic) from the Netherlands.

Did those ancient Europeans accidentally forecast near-perfect renditions of extinct reptiles that paleontologists would only discover centuries later? Clearly not. Yet they had no knowledge of these fossils back then. One explanation, now noted in the book’s updated introduction, is that those artists saw the animals—either alive or dead. A dragon carcass would be easier than a live one to approach close enough to sketch its detailed anatomy.

Over the centuries and across the continent, each artist had to decide what his or her St. George dragon would look like. Each might have sought the nearest, most familiar dragon to use as a model. Thus, an artist in one locale modelled his St. George dragon after local and living kind X, while a different artist in a different place (and/or time) modelled his St. George dragon after local and living kind Y. And so on. Dragon depictions with peculiar and identifiable features and forms argue more strongly than ever that real dragons lived in Europe into the Middle Ages.

Permian dragons

Finally, what does all this imply for the fossils? The Creation/Flood model has held all along that the Flood deposited the vast majority of Earth’s sedimentary strata within a single year. The animals captured and fossilized therein all lived, though probably not in the same place, through the 599th year of Noah’s life. Representatives of each kind of land animal (thus including dinosaurs and every other extinct land reptile) survived on the Ark. Their descendants dispersed after the Flood, and must have at points interacted with people. On this basis alone, creation researchers should have anticipated not just dinosaurs, but also extinct Permian and Triassic (non-dinosaur) land reptiles in ancient art.

This genuine European artwork reveals reptiles that span a supposed 200 million years’ worth of rock deposition. Yet they all lived with man. This refutes the entire ‘age of reptiles’ evolutionary idea. We now have access to multiple, clear, eyewitness depictions of mankind alive long after the Flood with not just dinosaurs, but with Permian reptiles.

References and notes

- Nelson, V., Dire Dragons, Unknown Secrets of Planet Earth, Untold Secrets of Planet Earth Publishing Co., Red Deer, Alberta, 2011. Return to text.

- Le Quellec, J., Bahn, P., and Rowe, M., The death of a pterodactyl, Antiquity. 89(346):872-884, 2015. Return to text.

- De Pastino, B., Prehistoric Utah rock art does not depict a pterosaur, study confirms, Western Digs. 31 December, 2015; westerndigs.org. Return to text.

- Evolutionists believe that dinosaurs first evolved in the ‘middle Triassic’ about 240 million years ago, and disappeared at the ‘Cretaceous—Paleogene extinction event’ 66 million years ago. Some of the animals in the book were non-dinosaurian reptiles that evolutionists assign to the ‘lower-Triassic’ and ‘Permian’ periods. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.