The Octopus

Intelligent, evolution-defying master of camouflage

In captivity, the octopus is renowned for ‘unruly’ behaviour. E.g. tampering with or blocking outlet valves, causing its tank to overflow.1 And it can be very difficult to keep contained. It can squeeze its boneless body through a space not much bigger than its eye—just sufficient for its only hard part, the parrot-like beak, to pass.2

‘Inky’ the octopus achieved international notoriety in 2016 when he escaped from New Zealand’s National Aquarium. ‘Tracks’ found next morning showed Inky had forced himself through a small gap at the top of his enclosure, then travelled across the floor to a drainpipe and on to the sea.3

Other institutions that have kept octopuses tell of similar great escapes, and also of their overnight raids to catch and eat fish in other tanks. Along rocky coastlines, wild octopuses have been observed launching themselves onto the land to ambush unwary crabs. One captive octopus learned to turn off electric lights by using its siphon/jet to squirt water at them, short-circuiting the power supply. Another took an apparent dislike to a certain attendant, squirting a stream of salty water at her whenever she came within range. Even after the attendant was absent for months, the octopus, not having squirted anyone else meanwhile, evidently recognized her, immediately resuming the squirting attacks.4

Some see such behaviour as clear evidence of remarkable intelligence, though other researchers are more cautious. Traditional measures of animal intelligence aren’t easily applied—e.g. their ‘social interaction’, as octopuses are mostly solitary. Also, they are notoriously “hard to experiment on. … [S]ome of them refuse to do anything you want them to do—they’re just too unruly.”1 Researchers trying to test three octopuses with the classic ‘pull-lever-for-food’ experiment were stymied when one of them tried to pull a light into the tank, squirted water at anyone who approached, and prematurely ended the experiment by breaking the lever.

Too brainy?

Unquestionably octopuses are “pretty good at sophisticated kinds of learning”,1 e.g. able to open a screw-top jar from both the outside and inside.5 Scientists have often regarded tool-use by various apes—our alleged ‘closest evolutionary relatives’—as evidence of intelligence. However octopuses have similarly demonstrated strategic employment of such things as shells, human-discarded coconut halves, and stones. Possibly one reason for the reticence of some scientists to recognize such evidence of intelligence is that octopuses are nowhere near primates on the supposed ‘evolutionary tree of life’.

The octopus brain has approximately 500 million neurons—about the same as a dog’s. Given its relatively short lifespan (1–2 years), Harvard professor Peter Godfrey-Smith dubbed its braininess an evolutionary paradox—like “spending a vast amount of money to do a PhD, and then you’ve got two years to make use of it … the accounting is really weird.”1

Two-thirds of the neurons are in the limbs (or tentacles, often referred to as arms or legs—see box below) giving each ‘a mind of its own’. A severed tentacle will continue to grope along the seabed. If it finds food, the lonesome limb will grab it (octopus suckers also have the power of smell/taste) and try to pass the food to where the mouth would normally be. Incredibly, an octopus can regrow a tentacle to replace exactly the length that was severed—neurons, suckers, taste receptors, muscles, chromatophores (the amazing colour-changing structures in its skin) and all.6

A ‘cascade’ of molecular events

This ability to regenerate lost tissue, organs, and whole appendages has attracted much research interest (the medical ramifications for ourselves could be huge). While much of the complex biochemistry is still a mystery, what is known is that a “cascade of chemical signals” is involved in the “orchestrating” of multiple “specific steps”.6 These trigger and control for example the arrival of a mass of stem cells and blood vessels at the injury site, and their subsequent mobilization/disappearance from there as the arm is progressively restored. In a biochemical ‘cascade’, each step is dependent on the one before it, raising a problem for the evolutionary view of origins.

If any step is missing or faulty the system doesn’t work, leaving no evident reason for ‘natural selection’ to ostensibly have favoured the hypothetical intermediate stages. So how could such a marvellous repair-and-regeneration system, which is there in anticipation of limb loss, have ever arisen by neo-Darwinian step-by-step evolution? (Which is ‘blind’, with no plans, foresight, or goals—as leading evolutionists emphasize.) Irreducible complexity is a huge challenge for evolutionary theory.

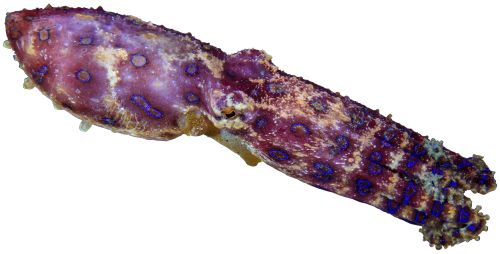

Maestros of Masquerade

Octopuses can match their background (e.g. a coral reef) by instantly changing colour so perfectly, even a keen observer loses sight of them. Their skin has been described as being “like a pixelated video screen”, with the top layer containing tens of thousands of tiny pockets of different colours that can be independently opened and closed so as to exhibit the colour scheme of the moment. Underlying that surface display is a layer of reflective cells stacked like a diffraction grating to create iridescence, with yet another layer beneath them to further bounce back incoming light. In the blue-ringed octopuses (Hapalochlaena spp.), the colour is aposematic or warning, in this case that they have a highly venomous bite.

The camouflage is not static; the skin really can display flashing pulses of colour like a video screen, seamlessly incorporating the passing shadows from clouds, the dappled shimmering of the seabed as waves scatter the sun’s rays, or even forked lightning. Added to all that, some octopuses can shape-shift so as to mimic the form and movement of other creatures (e.g. the banded sea snake, and lionfish) in an apparent effort to deter would-be predators.2

- Roberts, C., Just how smart is an octopus?, washingtonpost.com, 6 January 2017.

- Smith, C., The mimic octopus: The ocean’s eight-armed impressions artist.

‘Alien’ biology

Also, a mind-stretching self-admitted challenge for evolution theorists is the fact that octopuses are so “utterly different from all other animals, even other molluscs”, leading to some scientists even dubbing them ‘aliens’.7 In a 2018 paper, 33 evolutionary scientists even seriously argued that octopus biology would have needed an input of genes from an extraterrestrial source!8 They wrote that such things as a “sophisticated” nervous system, “intelligent complexity”, eight prehensile arms, camera-like eyes similar to ours, and instantaneous camouflage via the ability to change colour and body shape “appear suddenly on the evolutionary scene”. The authors also noted that “cephalopod phylogenetics [= attempted ‘evolutionary trees’ for octopuses, squid, etc.] is highly inconsistent and confusing”.

Furthermore, the mooted evolutionary progression from ‘primitive’ nautilus to cuttlefish to squid to octopus would have needed “transformative genes … [which] are not easily to be found in any pre-existing life form—it is plausible then to suggest they seem to be borrowed from a far distant ‘future’ in terms of terrestrial evolution, or more realistically from the cosmos at large.”8 In terms of mechanics, the authors suggest that a population of early squid received the necessary genes for octopus evolution from infection by extraterrestrial viruses carried to Earth via an asteroid or comet. Alternatively, “cryopreserved octopus embryos soft-landed en masse from space 275 million years ago.”8

What are the chances?

Of course, as the 33 authors acknowledge, such an extraterrestrial origin “runs counter to the prevailing dominant paradigm”, and ‘terrestrial-only’ evolutionists were quick to object. Ken Stedman, a virologist and professor of biology at Portland State University, pointed out that modern retroviruses are extremely specific about which hosts they infect. A retrovirus from space wouldn’t have evolved to be specific for Earth-based creatures, Stedman said, and “certainly not specific enough for something like a squid.”9 Karin Mölling, a virologist at Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics, says the extraterrestrial notion “cannot be taken seriously. There is no evidence for it at all.”9

But objectors to the extraterrestrial hypothesis did not provide any reasonable answer to the core ‘octopus evolution’ problems that drove the 33 scientists to look beyond Earth in the first place.

Arms or legs?

Are the eight tentacles of octopuses best called ‘arms’ or ‘legs’? (It’s not ‘octopi’, incidentally; ‘octopus’ is from Greek oktōpous = eight feet, not Latin, so its classical plural is the rarely used ‘octopodes’ (ὀκτώποδες). But as a now-common English word, it takes the usual plural).

One study found that while “all the limbs basically have the same capabilities”, the octopus tends to favour particular limbs for certain functions. E.g. when eating, the 3rd limb is most often used. When swimming, all tentacles are generally employed. When crawling around, the front two tentacles are most actively used for “exploratory work”, the limbs immediately behind them also used “if further investigation is needed”. The two rearmost provide most of the propulsion and movement (walking, or pushing off the seabed to swim), leaving the front tentacles free for pouncing on prey. Researchers quipped that “octopuses effectively have six arms and two legs.”

- Octopuses have more arms than legs: research, abc.net.au, 14 August 2008.

- Thomas, D., Octopuses have two legs and six arms, telegraph.co.uk, 12 August 2008.

‘Intelligent complexity’ = Intelligent Designer

An oft-heard atheist challenge is, “Where’s the evidence for creation?” Well, according to Romans 1:20, anyone who fails to see the hand of the Creator in nature is “without excuse”. The octopus’s aforementioned intelligence and ‘intelligent complexity’ surely suffice on their own to point to the existence of an even-more-Intelligent Designer behind it all. And consider also the amazing design of octopus skin, which enables them to spectacularly camouflage themselves (see Maestros of Masquerade above).

Engineers want to ‘steal’ octopus design secrets

The octopus is replete with design features that human engineers are striving to copy (a field known as biomimetics). Example: Octopus suckers attach much more strongly than human-designed suction cups. Researchers suspected this was because the series of radial grooves in them increased the area subject to pressure reduction during attachment. They confirmed this by laser-engraving the attachment surface of artificial suction cups. All the groove patterns tested enhanced attachment, but the best was the one “most similar to octopus sucker morphology.”10 Looks like the Master Engineer knew what He was doing.

Other researchers, too, recognize that octopus design features are worth trying to understand and copy, even if they don’t credit and acknowledge the One from whom they’re ‘stealing’ the ideas:

“Looking at nature’s achievements is reasonable in order to try to understand and replicate animal capabilities by deriving and ‘stealing’ the basic concepts which enable such behaviours.”11

And:

“The project then explored the technologies for stealing the main secret of the octopus arm, i.e. the muscular hydrostat, and developing soft robot bodyware, soft actuators, a sensitive skin, and suckers.”12

Soft-bodied wonder

With no bones or shell, octopus arms are indeed a muscular hydrostat, with tightly packed muscle fibres arranged into transverse, longitudinal and oblique muscles. Selective contractions of transverse and longitudinal muscles allow bending (in any direction, at any point on the arm, and able to propagate along it) and elongation/shortening (by up to 70%!), while co-contractions stiffen the arm.13 Contractions of oblique muscles allow torsions (twisting).14

In tandem with the octopus’s capacity to greatly deform its entire body so as to ‘pour’ itself into tight spaces, no wonder the octopus is the envy of engineers trying to advance their pursuit of soft-bodied robotics. The possible medical applications are especially tantalizing, e.g. an endoscope with controllable stiffness, capable of moving, reaching out, and grasping.11

Exquisite fossils

When an octopus dies, if not gobbled by scavengers, its soft body rapidly decays to be “little more than a slimy blob”.15 Mark Purnell of the Palaeontological Association remarked that finding a fossil octopus “is about as unlikely as finding a fossil sneeze”.15

So how to explain octopus fossils, ‘dated’ to 95 million years, with “an astonishing degree of preservation”, displaying fossilized arms, muscles, suckers, internal gills, even ink, and showing “a surprising similarity to modern-day octopuses”?15

Here’s how. The problem, according to 2 Peter 3:3–6, is that evolutionary scientists are willingly ignorant of creation (about 6,000 years ago) and the subsequent global Flood of Noah’s day (about 4,500 years ago). Embrace biblical thinking instead, and we see fossils are a legacy of unusual and rapid burial in sediment-laden and mineral-rich floodwater.16 Also, octopuses have always been octopuses, reproducing according to their kind17 (Genesis 1:21), just as God programmed them to do—with a plethora of spectacular design features more than sufficient for them to survive in their allotted habitat. The octopus does indeed fit the Psalmist’s astute observation: “O LORD, how manifold are your works! In wisdom have you made them all” (Psalm 104:24).

References and notes

- Hunt, E., Alien intelligence: the extraordinary minds of octopuses and other cephalopods, theguardian.com, 29 March 2017. Return to text.

- Roberts, C., Just how smart is an octopus? washingtonpost.com, 6 January 2017. Return to text.

- Hunt, M., Inky the octopus squeezes through drain pipe … , stuff.co.nz, 12 April 2016. Return to text.

- Montgomery, S., Deep intellect, orionmagazine.org. Return to text.

- See youtube.com videos: ‘Octopus opening a jar to get dinner’ and ‘Octopus can open jar’. Return to text.

- Harmon, K., How octopus arms regenerate with ease, blogs.scientificamerican.com, 28 August 2013. Return to text.

- You might not believe it but octopuses are ‘aliens’, reveals new DNA study, inquisitr.com, 13 August 2015. Return to text.

- Steele, E., and 32 others, Cause of Cambrian Explosion—Terrestrial or cosmic? Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology 136:3–23, 2018 | doi:10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2018.03.004. Return to text.

- Specktor, B., No, octopuses don’t come from outer space, livescience.com, 17 May 2018. Return to text.

- Tramacere, F., and 3 others, Octopus-like suction cups: from natural to artificial solutions, Bioinspir. Biomim. 10(3):035004, 2015 | doi:10.1088/1748-3190/10/3/035004. Return to text.

- Ranzani, T., and 3 others, A bioinspired soft manipulator for minimally invasive surgery, Bioinspir. Biomim. 10(3):035008, 2015 | doi:10.1088/1748-3190/10/3/035008. Return to text.

- Mazzolai, B., and Laschi, C., Octopus-inspired robotics, Bioinspir. Biomim. 10(3):030301, 2015 | doi:10.1088/1748-3190/10/3/030301. Return to text.

- Hanassy, S., and 3 others, Stereotypical reaching movements of the octopus involve both bend propagation and arm elongation, Bioinspir. Biomim. 10(3):035001, 2015 | doi:10.1088/1748-3190/10/3/035001. Return to text.

- Cianchetti, M., and 4 others, Bioinspired locomotion and grasping in water: the soft eight-arm OCTOPUS robot, Bioinspir. Biomim. 10(3):035003, 2015 | doi:10.1088/1748-3190/10/3/035003. Return to text.

- Day, S., Fossil sneeze caught, geolsoc.org.uk, 2009. Return to text.

- Graham, G., Fast octopus fossils reveal no evolution. Return to text.

- Probably all species of the superfamily Octopodoidea, most of which are in the genus Octopus, are the same ‘octopus kind’ (for more on created kinds: Ligers and wholphins? What next?). Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.