Journal of Creation 33(2):33–37, August 2019

Browse our latest digital issue Subscribe

A book about human errors that don’t exist

Human Errors: A panorama of our glitches, from pointless bones to broken genes by Nathan H. Lents

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston, MA, 2018

It is the responsibility of an author to do basic research before writing a book. I have read few books with as many gross errors as this one, mostly in chapters 1, 3, and 4. Although entertaining and well-written, most of the examples in these three chapters are incorrect or not up to date. One example of many is the so-called placement of the retina photoreceptors called backward because they face away from the source of light instead of toward it (pp. 2–8). A major reason for this design, as has long been known to ophthalmologists,1 is that both the rods and cones must physically interact with the retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells, which are located at the back of the eye. The RPE provides nutrients and oxygen to the retina cells, one of the most bioactive cell systems in the body.

The RPE also recycles photopigments and its opaque layer absorbs excess light. It is even essential in both the development and the normal function of the retina. The reverse would not work. Lents cites the octopus as an example of good design only because its photoreceptors face the front of the eye. In this case, the equivalent RPE system is located on each side of the rods and cones, not in the back of them as is true in humans. The octopus system is less sensitive, but works because their vision is sensitive mostly to movement in a fairly dark underwater world. Lents is also evidently unaware how the arrangement allows the light to be filtered through a fibre optic plate comprising the Müller glial cells. This plate filters out stray light, increases image sharpness,2 and separates the colours to optimize day vision without harming night vision.3

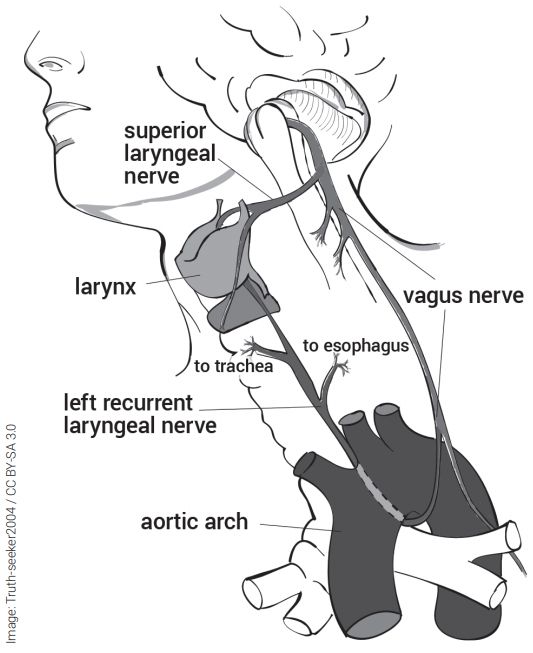

The recurrent laryngeal nerve

Another example Lents cites is the recurrent laryngeal nerve (p. 14) which he argues is much longer than required because, instead of travelling directly to the larynx, it loops around the aortic arch then travels back up to the larynx. The superior laryngeal nerve is not one nerve that has one function as implied by Lents and others, but has several functions. It divides into branches which control the internal laryngeal muscle, and innervate muscles responsible for pitch, controlling loudness, and vocal fatigue. The three main branches of the recurrent laryngeal nerve innervate several muscle bundles including the thyroarytenoid muscle, the posterior cricoarytenoid muscle and the lateral cricoarytenoid muscle. We know this because damage to the nerves that innervate these muscles affects articulation, causing speech to be ‘slurred’ or ‘garbled’. The existing recurrent laryngeal nerve system design serves to make fine adjustments to larynx control in order to improve speech quality.4

Other examples Lents discusses include the upside-down maxillary nasal sinuses which he claims are poor design because they often must drain against gravity. They are located behind each upper cheek above the teeth, one on each side of the nose (pp. 12–13). Given their many functions, which include lubricating, warming and moistening the air we breathe, the nasal sinuses must be designed to completely surround the nasal cavity. All the paranasal sinuses produce resonance to allow each human voice to be so unique that voice analysis can often accurately identify persons that make phone threats.

The maxillary nasal sinuses use cilia to move the sinuses’ contents upward, and the main problem is when they become inflamed, which causes problems for all of the paranasal sinuses. The maxillary nasal sinuses are only upside down when humans are sitting up or walking. When lying down, they have the advantage of gravity helping to drain them, but the other paranasal sinuses have the disadvantage the maxillary sinuses have when the person is standing upright.

The poor knee design claim

The injury-prone knee (pp. 32–33), which Lents also cites as an example of poor design, is not injury prone as a result of poor design. Almost all knee problems are due to body abuse, overuse, injury, or disease, and not poor design. The knee is the largest, most complex joint in the human body, but it is also one of the most used (and abused) body joints. It is also considered a marvel of engineering and design by engineers. Furthermore, no evidence exists of knee evolution in the abundant fossil record. Mammals either have the irreducibly complex human type of knee,5 or the simpler non-human type.

The herniated disk and other back problems he mentions (p. 26) do not result from poor design or maladaptation because bipedalism was superimposed by evolution on a skeleton previously well-adapted for quadrupedal motion as Lents claims. Rather, it is caused by abuses of the body that are common in modern life. This includes lack of exercise, poor posture, stress, and being in unusual positions for long periods of time, such as bending forward on an assembly line while working or spending hours on a computer. In short, anything that decreases the natural and well-designed lordosis (backward curve) causes problems, the opposite of the Darwinism-based approach.6

The too many bones claim

Next covered are claims of foot and hand problems caused by too many bones (p. 29). Lents claims human feet comprise 26 bones because we evolved from ape-like ancestors that required flexible feet to grasp branches. Thus, humans have an excess number of foot and hand bones because we no longer are arboreal (p. 29). However, the current design allows the human foot and hand to be more flexible, to our advantage in many obvious ways, than would be the case if the hands and feet had fewer bones as advocated by Lents.

The claimed birthing problem

The last example mentioned is the claim that birthing problems commonly result because the female birth canal size has not significantly evolved since our ape common ancestor, but the human head has evolved significantly since then (pp. 106–107). Actually, this is rarely a problem. The birthing system’s design ensures that almost all healthy mothers birth without problems except the birthing pain mentioned in Genesis due to Eve’s sin. These mechanisms include a pelvis consisting of two large hip bones that meet at the front of the body connected together by a fibrous joint composed of dense connective tissue. During pregnancy, a hormone called relaxin causes this joint to become more flexible, allowing the birth canal opening to significantly increase in size to permit a healthy mother to birth the baby with very few complications.

The skull of the newborn is also fairly flexible and, in almost all cases, able to conform to the birth canal opening. An infant’s skull is made up of six separate cranial bones held together by strong, fibrous, elastic sutures. The flexibility of the sutures allows the bones to move to enable the baby’s head to pass through the birth canal without pressing on, and damaging, the brain.

Any internet search will reveal that Lents is quoting Darwinists who are not anatomists, nor up to date. As Stephen Jay Gould noted, once a wrong idea becomes part of academia, it may take a long time to remove it. Haeckel’s fraudulent embryos took almost a century before they were finally largely, but not completely, removed from the textbooks.

Chapter 2 covers nutrition, which is not an example of poor design but how medicine deals with health problems. Lents notes that most animals’ diets are controlled by instincts and, in contrast to humans, can make most of the amino acids and vitamins required for good health. He cites the fact that cows can thrive on a diet largely of grass and do not need a “delicate mix of legumes, fruits, fiber, meat, and dairy like humans are told to eat” (p. 36). One example is vitamin C. Aside from fruit bats, guinea pigs, primates, and humans “nearly all animals on the planet make plenty of their own vitamin C, usually in their liver” (p. 38). Lents explains that humans have the genes required to manufacture vitamin C except for what he calls a “broken gene”, namely the GULO gene.

Mutations are not evidence of poor design

This condition, of course, is not a result of poor design, but due to one or more mutations, as are the other 6,000 or so mutation-caused diseases. And this would be expected from the Fall, something which Lents ignores—as do most ‘poor-design’ propagandists. This is the opposite of evolution where mutations are ultimately the only source of genetic variety that natural selection uses to improve an organism’s fitness.

Some of these mutation-caused diseases, such as phenylketonuria (PKU), can be treated by dietary modifications. In this case, the body cannot metabolize the amino acid phenylalanine into the amino acid tyrosine. Persons with this genetic disease, which often used to be fatal, can do very well with dietary modifications, including major reductions of foods high in phenylalanine, mostly high-protein foods such as dairy products, red meat, fish, chicken, eggs, certain beans, and nuts. These foods cause high blood phenylalanine levels which are toxic to the nervous system for people with the PKU mutation.

Lents also inadvertently undermines evolution from simple one-celled organisms to the higher, complex organisms such as primates when he notes that many animals located on the base of the phylogenic tree can make all 20 amino acids normally required, whereas humans can make only 11, and likewise many simple organisms can make all of the vitamins they require, yet in humans there are 13 vitamins called ‘essential’, meaning they must come from our diet.

Actually, vitamins K and B12 are made by bacteria in our colon, but are poorly absorbed there. Lowly bacteria, but not the higher plants or animals, possess the complex set of enzymes required for B12 synthesis. Vitamin K is a necessary cofactor for prothrombin and certain other blood clotting factors. The same is true of other vitamins.

These complex organic compounds are manufactured at the base of the food chain in the lower, supposedly simple animals, and they move up the food chain into the higher-level, more-evolved animals. If humans could obtain a perfectly healthy diet, due to our bacterial biome, by consuming grass alone, this would if anything support the plausibility of a pre-Fall vegetarian diet. Nonetheless, today we require a complex diet, possibly as an end result of the Fall.

Lents’ review of mutations includes noting that many germ line “mutations are harmful because they disrupt the function of a gene” and the “poor offspring that inherit a gene mutation from their father or mother are almost always worse off for it … but sometimes the harm that a mutation brings is not immediate” and these mutations, if they do not result in human or animal “short-term loss in health or fertility, it won’t necessarily be eliminated. … If this mutation caused harm only far down the road, natural selection is powerless to immediately stop it” (p.71). Lents calls this evolution’s blind spot, correctly noting “the human genome contains thousands of scars from harmful mutations that natural selection failed to notice until it was too late” (p. 71). This is not a result of poor design, but damage caused by mutagens.

The pseudogene claim

The discussion of pseudogenes, which he defines as “once-functional genes that became mutated beyond repair,” ignores the finding that many of these once misnamed pseudogenes are now known to have a function. The number he gives is “nearly twenty thousand” (p. 73). In answer to the question of “why nature wasn’t able to fix this problem the same way it created it: through mutation,” he answers:

“That’d be nice, but it’s nearly impossible. A mutation is like a lightning strike … . The odds of lightning striking the same place twice are so infinitesimally tiny as to be nonexistent. What’s more, it’s exceedingly unlikely that a mutation will fix a broken gene because, following the initial damage, the gene will soon rack up additional mutations” (p. 72).

If the odds of repairing a damaged gene are so infinitesimally small, what are the chances of creating a functional gene from random letters, or even converting one gene into another as evolutionists postulate? Here again, he has documented the reasoning behind the mutational degeneration idea creationists support based on evidence. Lents here supports the view that evolution is true, but is going backwards, which is a major problem for Darwinism. Lents does not even try to defend the orthodox evolutionary view that the accumulation of mutations causes evolution from molecules to mankind, but just assumes it is true.

Junk that is not junk

Chapter 3 on Junk in the Genome repeats the long-refuted arguments that only a small percentage of DNA is functional. The junk is theorized to be left over from our evolutionary past, or was once functional, but was damaged as we evolved from lower life forms. On the very first page of this chapter, Lents admits that the term junk has fallen out of favour due to the discovery of functions for “some parts of this junk” (p. 65). Lents also admits “it may very well turn out that a large portion of so-called junk DNA actually serves some purpose”, a statement that is totally ignored in most of the rest of this chapter (p. 65). It appears that after Lents wrote this chapter, he became aware that many of the conclusions by evolutionists have turned out to be wrong, thus he rewrote the first page, but left the rest of the chapter alone.

An example is on page 67 where he notes we have 23,000 genes and asks what does the rest of the DNA do? His answer: “nothing” (p. 67). He then adds that only 3% of the genome consists of words, the rest is “gobbledygook”, i.e. junk! (p. 67). He also writes that the 23,000 useful genes that make up 3% of the genome “are a wonder of nature” but most of the “other 97 percent of human DNA is more of a blunder … . Some of it, indeed, is actually harmful” (p. 69). Last, he adds that “over a million cell divisions per second” occur each day, and each “one of those cell divisions involves copying the entire genome, junk and all … just to copy your largely useless DNA.” He concludes, given “all of the nonsense encoded in the human genome it’s surprising that we turned out as well as we have.”

Lents’ book was released 1 May 2018 and had glowing reviews from many leading evolutionists and atheists. Long before this book was published, the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) research project was commenced. Its goal is to identify the functional elements in the human genome. It began in 2003 and is now in its 4th phase. So far, the 440 scientists from 32 laboratories worldwide have determined that 80% of the genome is useful, often for regulatory functions. The central conclusions from the pilot project were published in Nature on June 2007, a decade before Lents’ book was published. Lents either ignored this research or was not aware of it.

Lents admits the ‘evolutionary’ DNA design is “a simple but ingenious form of information coding, especially because it makes it very easy for genetic material to be copied again and again … a miraculous feat of evolutionary engineering but also the base of our very existence” (p. 66–67). This is only one of many examples where Lents informs the reader how evolution is intelligent, miraculous, ingenious, and other terms applying to sentient beings.

Lents unwittingly includes many other arguments against evolution in his book. For example, he notes:

“… even though humans have been evolving separately from some mammals for over a quarter of a billion years, we all have the same number of functional genes. In fact, humans have roughly the same number of genes as microscopic roundworms, which have no real tissues or organs” (p. 68).

My response to Lent’s claim is that the difference between the lower, simpler and higher more complex animals, is not primarily due to the functional genes but rather to the regulatory genes that Lents calls ‘gobbledygook’.

Birthing problems claim

Chapter 4 covers topics such as “why our enormous skulls force us to be born way before we are ready and humans have the lowest fertility rate and the highest mortality rate for infants” (p. 92). Human families have low fertility rates because all primates but humans, and all animals, are largely governed by inborn instincts. Humans require years before they can assume adult roles; most primates require only months. Furthermore, many families used to have eight, ten, or more children largely to ensure that some survived. The human mortality rate has been reduced enormously by cleanliness, antiseptic measures, vaccination, antibiotics, and even simply washing one’s hands before helping with delivery has seen a significant improvement as Semmelweis discovered.

Chapter 5 reviews the innovations provided by modern medicine, including antibiotics. Lents fails to show how the medical problems covered in this chapter are due to poor design. Lents admits that infectious diseases and most of the other medical concerns he covers are not design flaws, but “are our own fault, not nature’s” (p. 129). He notes the most common ailments in the West are head colds and gastroenteritis, both reduced by proper cleanliness and a good diet (p. 127). Much of this chapter, as well as chapters 2 and 4, are mostly about disease cause and treatment.

Chapter 6 covers the brain and mostly describes its quirks such as optical illusions, the tendency to take risks, memory distortion, and behaviour such as smoking, drug use, and gambling. Lents acknowledges in some detail the fact that the human brain is an amazing structure, adding the fact that even “modern supercomputers cannot compare to the fast and nimble capabilities of the human brain. … but also in its ability to self-train” (pp. 157–158). None of these examples illustrate poor design but mostly poor judgement on the part of many persons. The chapter relies heavily on the work of New York University psychologist Gary Marcus.7

Conclusion

The stated goal of Lents is to document the poor design claims in the human body, but he fails miserably. Only three chapters directly attempt to achieve this goal, chapters 1 and 3 and parts of 4. Chapter 3 has been carefully rebuked by extensive new research, including the ENCODE project. The claims by Darwinists given in Chapters 1 and 4 have likewise been refuted by empirical research, by both evolutionists and creationists.

References and notes

- Gurney, P., Is our ‘inverted’ retina really ‘bad design’? J. Creation 13(1):37–44, 1999. Return to text.

- Franze, K. et al., Müller cells are living optical fibers in the vertebrate retina, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA, 10.1073/pnas.0611180104, 7 May 2007; pnas.org/cgi/content/abstract/0611180104v1. Return to text.

- Labin, A.M. et al., Müller cells separate between wavelengths to improve day vision with minimal effect upon night vision, Nature Communications 5(4319), 8 July 2014 | doi:10.1038/ncomms5319. Return to text.

- Bergman, J., Recurrent laryngeal nerve is not evidence of poor design, Acts and Facts 39(8):12–14, 2010. Return to text.

- Burgess, S., Critical characteristics and the irreducible knee joint, J. Creation 13(2):112–117, 1999. Return to text.

- Standing upright for creation [interview with the late human spine expert Richard Porter], Creation 25(1):25–27, 2002. Return to text.

- Marcus, G., Kluge: The Haphazard Construction of the Human Mind, Houghton Mifflin, Boston, MA, 2009. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.