The Birka Pinhead

Viking ‘dragons of the sea’ defy evolutionary history

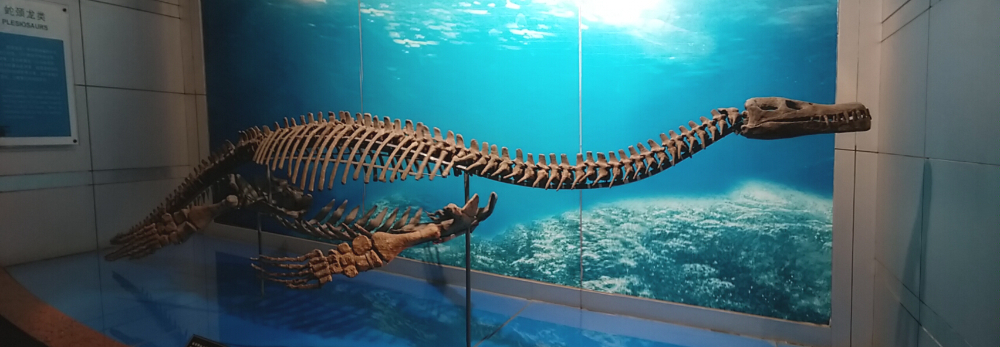

“When dinosaurs ruled the earth, plesiosaurs roamed the seas”1

This is the evolutionary dogma taught about these incredible dragons of the sea.2 And just like dinosaurs, the evolutionary timeline places the extinction of plesiosaurs at around 66 million years ago, well before the origin of mankind. However, a recent discovery, besides solving a nearly 130-year-old mystery, adds another strand of evidence that unravels the evolutionist’s chronology, and points to a different history.

The pinhead discovery

A soapstone carving discovered in Birka, Sweden, 1887, had suggested that Vikings adorned themselves with tiny metal dragon heads on their clothes-fastening pins. While the carving looked like a mould for casting such dragon pinheads, none of them had ever been discovered, that is until recently.3

Excavations in Black Earth Harbour, Birka, have now revealed a small dragon pinhead which very closely resembles the soapstone mould. Cast in tin-rich alloy, with a small quantity of added lead, it weighs a mere 13.5 g (0.5 oz), measuring only 45 mm (1.8”) long, 42 mm (1.7”) wide at the snout, and the neck measuring 17 mm (0.7”) in breadth. It also has a circular hole at the bottom with some corroded iron which was most likely the end of an attached iron pin that would have adorned Viking clothing.

Pinheads to figureheads

The double-sided dragonhead is very distinctive with its wide open mouth full of sharp teeth, and ‘curls’ extending down its long slender neck. It is believed that the Viking jewellery corresponds directly to dragonheads placed on the stem of Viking boats, called dragon ships.

Similarly shaped iron curls were also found on the stem of a Viking burial ship in Denmark. The Ladby ship (named after Ladby, Denmark, where the boat is on display in a museum) was discovered in 1938 and is thought to be the pin’s counterpart. While the dragon figurehead had disintegrated before the Ladby ship was found, the positioning of the iron curls on the stem have led researchers to conclude that it likely had the same style of dragonhead as the pin.4 Both the pinhead and the boat are thought to be from around AD 900.

Dragon ships have become inexorably linked to Vikings as a great symbol of their age. These Viking warships were called drekar (singular dreki), the Old Norse word for dragon, i.e. dragon ships. “The designation of these warships as drekar derives from the practice of placing carved dragonheads (drekahǫfuð) on the ships’ stem (stál), while the sternpost could become sculpted as a dragon’s tail (sporðr)”.5 The oars may have served to complete the look, akin to the flippers of the creature the boat was meant to represent.

What were they trying to depict?

The consistency of these sorts of representations of a large reptilian sea creature by Viking seamen strongly suggests that they were trying to depict a real creature that had been observed and described (allowing for some distortion by time and retelling, of course, especially if sightings were rare in more recent times). But there is no living marine reptile that comes anywhere near such a representation. The only serious contenders are the large, most likely extinct marine reptiles known from the fossil record.

Of these, a plesiosaur comes the closest to matching the Viking depictions. The iconic image of the long slender neck of a plesiosaur rising out of the water is much the same as that depicted by the stem of the Viking dragon ship. Other large extinct marine reptiles, such as mosasaurs or ichthyosaurs, have flippers and tails, but they do not have the same elongated necks as plesiosaurs.

Not just the Vikings

There are numerous historical accounts of similar plesiosaur-like animals:

- On 6 July 1734, Lutheran missionary Hans Egede, while off the coast of Greenland observed a sea serpent longer than their ship, resembling nothing he had seen before. It “raised itself so high above the water that its head reached above our main top. It had a long sharp snout…. Large broad flappers [sic], and the body was, as it were, covered with a hard skin, and it was very wrinkled and uneven on its skin; moreover on the lower part it was formed like a snake”.6

- In the 1840s, the HMS Fly was in the Gulf of California. Captain George Hope stated that while the sea was calm and transparent he saw, “at the bottom, a large marine animal, with the head and general figure of an alligator, except the neck was much longer, and instead of legs the creature had four large flappers [sic], somewhat like those of turtles, the anterior pair being longer than the posterior”.7

- In 1848, the HMS Daedalus was between the Cape of Good Hope and St. Helena when at four o’clock in the afternoon its experienced Captain Peter M’Quhae and the crew observed a sea serpent for about 20 minutes. It held its snake-like head about four feet out of the water, atop a neck about 40 cm (15 inches) inches in diameter, and had a body about 18 metres (60 feet) long that lay like a straight line on the surface. It had a jaw full of large jagged teeth8 when it opened its jaws, and interestingly, had “something like a mane of a horse,or rather a bunch of seaweed, washed about its back”.9 Perhaps this is what the Birka pinhead and the Ladby boat were trying to depict on the neck of their dragon by way of the ‘curls’? There may have been frills on the back of a plesiosaur that, because they were composed of soft tissue, have not yet been found preserved in the fossil record.

Not millions of years old

Rather than adding anything to the evolutionary narrative, the Birka dragon pinhead, Viking dragon boats, and other historical depictions and descriptions help to pin down the true history of these wonderful creatures. They certainly indicate that they did not die out 66 million years ago. Rather, God created them on Day 5 around 6,000 years ago, and some survived the Noahic Flood. They appear to have lived on the same Earth as humans up until relatively modern times, allowing for them to be observed and beautifully carved onto Viking dragon ships and represented on pinheads.

References and notes

- S.E.A. Aquarium, 9 facts about the prehistoric plesiosaur; emu3d.com, 24 Jul 2015. Return to text.

- Hunter, A., Are there dragons in the British Museum? Creation 39(4):54–55, 2017. Return to text.

- Kalmring, S. and Holmquist, L., ‘The gleaming mane of the serpent’: the Birka dragonhead from Black Earth Harbour, Antiquity 92(363):742–757, 2018. Return to text.

- Avaldsnes, Dragonships; avaldsnes.info, accessed 25 Aug 2019. Return to text.

- Ref. 3, p 749. Return to text.

- As recounted and translated from Danish in, Oudemans, A.C., The Great Sea Serpent (originally printed 1892, reprinted 2007), Cosimo Classics, p. 97. Return to text.

- Newman, E., Enormous undescribed animal, apparently allied to the Enaliosauri, seen in the Gulf of California, The Zoologist, 7:2356, 1849. Return to text.

- The Times newspaper, 9 Oct 1848. Return to text.

- M’Quhae, P., The Times newspaper, 13 Oct 1848. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.