Journal of Creation 35(2):44–52, August 2021

Browse our latest digital issue Subscribe

Horus—the deified Ham: part 1

One of the most famous and ancient of Egypt’s many deities was Horus, the falcon sun-god. In two articles I explore 12 key motifs of the life of Ham (Noah’s third son) drawn from the Genesis text. I then compare them to Horus drawn from Egyptian evidence, concentrating on the oldest evidence first. Part 1 looks at the following motifs: 1) Ham is 11th from Adam; 2) etymology of Ham’s name; 3) Ham came from a family of eight; and 4) Ham, the youngest of three brothers. These comparisons support the thesis that Ham was deified by the pagan Egyptians as Horus.

Biblical historical foundations

Egypt is eponymously called “the land of Ham” (Noah’s third son) in the Psalms (105:23, 27; 106:22) and “tents of Ham” (Psalm 78:51). Ham and Mizraim (Ham’s third son) appear together in Psalm 105:23 as designations for Egypt:

“… Israel came to Egypt (miṣrāyim); Jacob sojourned in the land of Ham (ḥām).”

Here, ‘Mizraim’ is the common name for Egypt throughout Scripture. Ham was a first-hand witness of the Flood, and likely lived to a similar age as his brother Shem (500 years post-Flood, Genesis 11:11). Via Noah’s teaching, Ham knew about creation and the pre-Flood world, knowledge he would naturally pass to his descendants. All this became paganized by the Egyptians. Ham’s great post-Flood lifespan, involvement in re-establishing of post-Flood civilization, and knowledge of the pre-Flood world, likely meant he had divine status conferred upon him by the Egyptians.

Twelve key motifs of Ham’s life

Twelve key motifs of Ham’s life extracted from Genesis 5–11 (listed in table 1) will be compared to Horus. If Ham was deified as Horus, then the latter will likely reflect these motifs in some discernible, though paganized way. Article 1 will explore motifs 1–4, Article 2 motifs 5–12.

Both articles will set out to explore these connections, concentrating on the oldest Egyptian textual evidence in each case. Before this, a brief discussion of who Horus was is in order.

Introducing Horus—the falcon-solar deity

Horus is one of Egypt’s oldest and most important deities, attested to from at least the beginning of the Dynastic Period, where the familiar form of the Horus falcon appears on the Narmer Palette (figure 1).

Horus appears in Old Kingdom Pyramid Texts (OK PTs), along with his sons, father, and mother (see part 2). Horus is depicted as a falcon (figure 2) or falcon-headed man, who was considered a creator god, as well as a form of the sun. His father was Osiris/Geb, with a notable brother, Seth. Myths associated with this family include the struggle between Horus and Seth after Osiris’s murder (see part 2). Here, both brothers injure each other through violent struggle for dominion. Horus loses his eye, which itself becomes deified as the moon (Thoth), and his healthy eye as the sun (RēꜤ). Numerous aspects of Horus became separate deities—for instance ‘Horus the child’, ‘Horus the elder’, and Horus in his solar form. Pharaohs became the living embodiment of Horus, and received their ‘Horus name’. Upon death they were believed to fly to heaven as the Horus falcon, to join RēꜤ in the solar barge, crossing the sky eternally.1 Much could be written regarding Horus; however, my two articles will be limited to a discussion of Horus’s possible connection to Ham, Noah’s third son.

Motif 1. Eleventh from Adam: Ham cf. Horus

The Genesis 5:1–32 chronogenealogies place Ham (with his brothers) 11th from Adam.2 Can a similar chronological relationship be discerned in Egyptian mythology, regarding Horus?

Egypt had a group of nine gods, called the Ennead, listed in OK PTs. Their sign was 9 flags, or vertical dashes, in Egyptian: psḏ.t (Wb 1, 558.12). They are listed in Pepis II PT-600§1655:

“O Great Nine that is in Heliopolis—Atum, Shu, Tefnut, Geb, Nut, Osiris, Isis, Seth, Nephthys—Atum’s children!”

“The Greater Ennead” psḏ.t-ꜤꜢ .t (Wb 1, 559.5) included Thoth, and Horus. When Osiris is accounted for, who appears as (father/brother) bystander, Horus’s position appears 11th from Atum, Unas PT-219§167–177:

“Atum … Shu … Tefnut … Geb … Nut … [Osiris] … Isis … Seth … Nephthys … Thoth … Horus.”

In my previous article,3 I made the case that Atum is the Egyptians’ paganized memory of Adam. Here in PT-219§167–177, Horus is placed 11th within the Greater Ennead—taking into account Osiris as bystander—from the Egyptian Atum. This may represent a paganized memory of the genealogies of Genesis 5:1–32 where Ham (and brothers) stand 11th in-line from Adam. Although the Ennead was considered a unified group (typically of nine), evidence suggests (e.g. PT-600§1655), that they were simultaneously considered consecutive offspring of Atum.4 However, what of the Greater Ennead’s ages? Is there a comparison here with the lifespans of the Genesis 5:1–32 patriarchs?

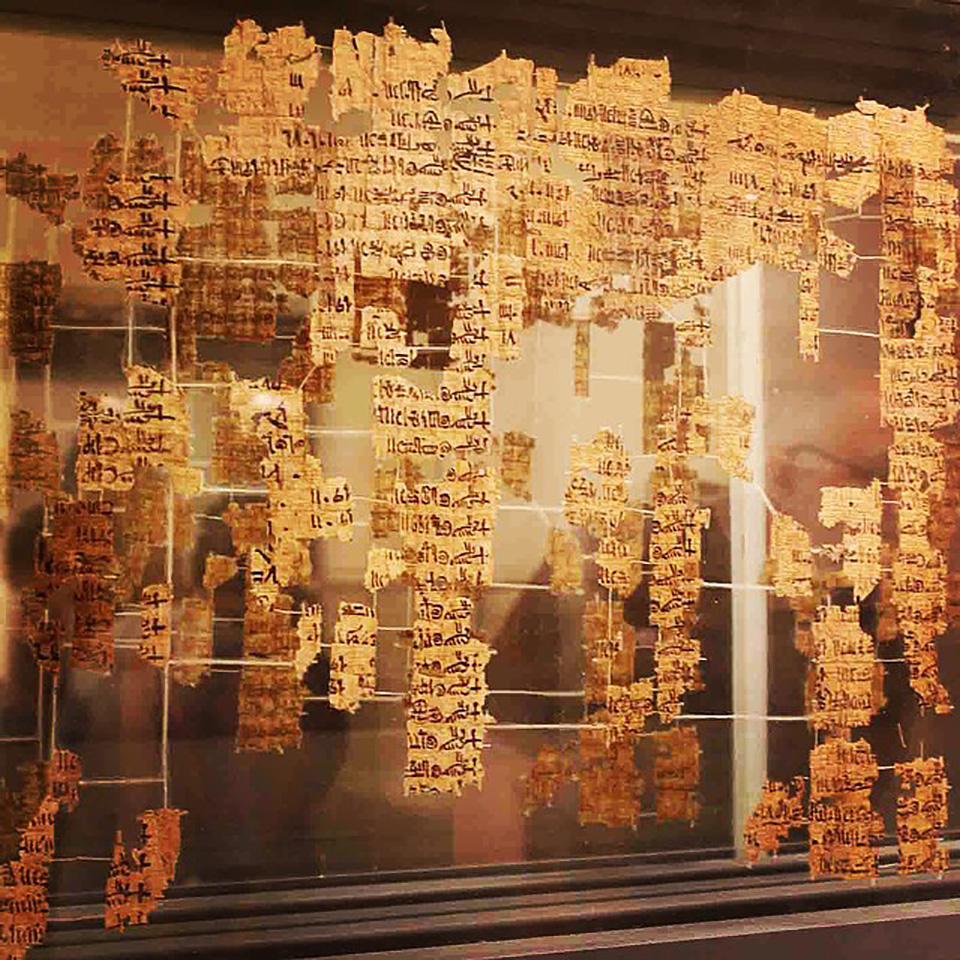

The 19th Dynasty Turin Canon papyrus (figure 3), though highly damaged, provides information regarding Egypt’s earliest history, which designates Egypt’s Predynastic rulers as šms.w-ḥr.w “Followers of Horus” (Wb 4, 486.16–19). Horus appears along with Seth and Thoth within columns 1 and 2 (fragments 11, 150) amongst the ‘gods and demi-gods’ with extraordinary reign lengths.5 Interestingly, the first names in the list contain likely references to creation, as well as Horus, Seth, and Thoth5 (known from the Greater Ennead).

Egyptologist K. Ryholt explains:

“The mythological kings consists [sic.] of gods, demigods, and spirits. … The first name [n ib […]] could be brought into relation with the primaeval ocean, the time before land existed and water was everywhere. The name ‘clod of the shore’ [pns.t n spt] can hardly be other than a reference to the creation of life out of lifeless matter, earth. The two latter names [‘possessor of noble women’ (ẖrḥm. wt-šps.w[t]) and ‘protector of [noble?] women’ (ḫw-ḥm.wt-[šps.wt?])] could, perhaps, relate to the creation of women. Further below, in the now lost part of column 2, there was a further transition from demigods to spirits, which continues in the first nine lines of column 3. The spirits have generally been interpreted as prehistoric kings, but it remains unclear how much historical importance should be attached to the information the king-list has to offer.”6

This sounds like a paganized reference to creation, Adam (from the earth), and Eve, up to later stages in the chronogenealogy, listed in Genesis 5:1–32. The nine lost lines may have included the number of mythical rulers described. That this papyrus seems to parallel Genesis from creation to the Flood was not lost on Eusebius, Bishop of Caesarea (AD 260/265–339/340), Roman historian, and exegete, who claimed access to material by Manetho (via the pseudepigraphical Book of Sothis). In W.G. Waddell’s 1964 translation of the Armenian version of Eusebius, he purportedly states:

“From the Egyptian History of Manetho, who composed his account in three books. These deal with the Gods, the Demigods, the Spirits of the Dead, and the mortal kings who ruled Egypt … [Eusebius lists these gods with Greek names, genealogically] … reckoned to have comprised in all 24,900 lunar years, which make 2206 solar years. Now, if you care to compare these figures with Hebrew chronology, you will find that they are in perfect harmony. Egypt is called Mestraim by the Hebrews; and Mestraim lived not long after the Flood. For after the Flood, Cham (or Ham), son of Noah, begat Aegyptus or Mestraim, who was the first to set out to establish himself in Egypt, at the time when the tribes began to disperse this way and that. Now the whole time from Adam to the Flood was, according to the Hebrews, 2242 years … .”6

Eusebius (relying on the extended LXX chronology) makes the unlikely claim the Egyptian chronology should be reckoned as months. Waddell in a footnote states:

“(Fn. 1) The Pre-dynastic Period begins with a group of gods, consisting of the Great Ennead of Heliopolis in the form in which it was worshipped at Memphis … . In the Turin Papyrus the Gods are given in the same order: (Ptah), Rê, (Shu), Geb, Osiris, Sêth (200 years), Horus (300 years), Thoth (3126 years), MaꜤat, Har … .”6 “

“(Fn. 5) ‘Demigods’ should be in apposition to ‘Spirits of the Dead’… . These are perhaps the Shemsu Hor, the Followers or Worshippers of Horus, of the Turin Papyrus … .”7

Although Eusebius overstates the case, we perhaps have in the remains of the Turin Canon and the Greater Ennead the Egyptian version of the Genesis’ chronogenealogies from Adam to Noah’s family, preserved, though in pagan form, from the original memory of Ham, deified here as Horus.

Motif 2. Horus cf. Ham—name etymology: violence, blackness, heat

Etymology of Ham’s name

As discussed in previous articles,8 Ham’s name can be understood via phonetic connections to similar-sounding words within the Hebrew text, biblical scholars call this ‘paronomasia’, (play-on-words, puns). At Genesis 6:11 the reason for the Flood is given—the earth is full of ḥāmas “violence, wrong” (HALOT-2980). A phonetic correspondence with ‘Ham’ is apparent in v. 11 (note orange-highlighted text):

“And Noah begat three sons, Shem, Ham (ḥām), and Japheth. Now the earth was corrupt in God’s sight, and the earth was filled with violence (ḥāmās)” (Genesis 6:10–11).

Theologian Moshe Garsiel states of the pun that it:

“… does not serve here merely as sound play but implies a connection between Ham and ‘lawlessness’. Later on (9:22–27), this son indeed displays the inferiority of his nature compared to his brothers.”9

The word ḥāmās occurs three times in Genesis (6:11, 13; 49:5). The meaning of this word becomes apparent at Genesis 49:5, within Jacob’s curse and blessings of his sons. The verse in question states: “Simeon and Levi are brothers—their swords are weapons of ḥāmās.” The context demands ‘violence’, not merely moral wrongdoing. It is this specific aspect of ḥāmās that lead to the Flood judgment. Two more phonetic connections to ‘Ham’ can be discerned after the Flood:

1. YHWH makes a covenant with Noah and his family, promising dependable seasons (Genesis 8:22) cold and “heat” (ḥōm).

“While the earth remains, seedtime and harvest, cold and heat (ḥōm), summer and winter, day and night, shall not cease.”

2. Ham’s grandson Nimrod (Genesis 10:8–10) at the construction of the tower of Babel provoked the next judgment of humankind. Cassuto noticed a play-on-words in Genesis 11:3,10 specifically in its construction materials:

… wəhaḥēmār hāyāh lāhem laḥōmer.

“… and the bitumen hath been to them for mortar” (Genesis 11:3, YLT).

The Babel rebellion was actualized through building, including with ḥēmār for ḥōmer, bitumen for mortar—specifically—black/dark coloured earthen materials. This word, ḥēmār, occurs three more times in the Old Testament. Next is Genesis 14:10, where the kings of Sodom and Gomorrah fell into ‘tar pits’, and lastly in Exodus 2:3, where in Egypt, the infant Moses’ basket was waterproofed with ‘tar’. Next, ḥōmer occurs in Exodus 1:14, when Israel laboured with ‘mortar’ for the Egyptians.

These similar ‘vocables’ (ḥāmās, ḥōm, ḥēmār, ḥōmer) phonetically connect to Ham. A theoretical semantic range for Ham’s name can be established when comparing similar-sounding Hebrew words in the early chapters of Genesis.11 Table 2 lists these earliest occurrences of phonetically connecting Hebrew words and their meaning, thereby offering vocabulary and semantic range by which the name ‘Ham’ can be understood.

From the evidence presented in table 2, Hebrew words found in Genesis (and the ancient book of Job) encapsulate three key concepts connecting phonetically to Ham’s name: 1) (physical) ‘violence’; 2) (earthen) ‘blackness/darkness’; and 3) (sun’s) ‘heat’, whereby etymologically, Ham’s name is understood. Are these three concepts integral to Horus? The following evidence (A–C) suggests this is so.

Phonetic considerations for Ham’s name in relation to Hebrew and Egyptian

Hebrew ḥām, is pronounced with an initial voiceless pharyngeal fricative ‹ḥ›, middle aleph ‹a› vowel, and terminal, nasal bilabial ‹m›.11 Furthermore, ‹ḥ› is grouped with the guttural fricatives: ‹ḫ›, ‹ẖ›.12 Phonetically similar ‘voiceless stops’ /k/ and /kh/ (excluding ḳ) coexisted in Egyptian, and survived into Coptic—for instance ⲕⲏⲙⲉ and ⲭⲏⲙⲓ represent two forms of km.t (‘Egypt’) (see section B).13

Through evidence of Semitic loan words into Egyptian14 Hebrew ḥeth (חֽ) is consistently transcribed into Egyptian as /ḥ/. Hebrew kaph כּ is transcribed into Egyptian as /k/ or /g/, never /ḥ/. Words containing the biliteral symbol km (as in km.t) provide no examples of Semitic exchange. Therefore, from established phonetic evidence it cannot be proven that Hebrew Ḥam and Egyptian km are related names, despite their superficial phonetic similarities. However, two examples of Hebrew words, meaning ‘black’ (Job 3:5, hapax legomenon) and ‘hot’ (Genesis 43:30, three occurrences) are spelled with Hebrew ‹k›, offering a possible phonetic relationship, which requires further research.

A) Violent Horus—the attacker-spirit (kk)

The following textual evidence associates Horus with struggle, violence, and war. For instance, the divine epithet tkk, means “attacker, to attack” (Wb 5, 336.2–11). The significance of the root kk will be discussed in motif-3. This is found in OK PT:

Teti PT-292§433a.

ntk tkk.n tk.j jkn-hj

“You’re one the attacker attacked, jkn-hj-Snake!”

The one attacking is explained and the epithet applied to Horus in a Middle Kingdom Coffin Text (MK CT): CT-885.

jntk tkk ntk ḥr.w nn.w sp-2 ḏ.t r p.t

“You are the attacker, you, Horus! Sink down wearily, Cobra, from heaven!”

The Egyptian Book of the Dead (BOD) glorifies the violence of Horus, for example chapter 19 (22nd Dynasty) states:

“Osiris N. has repeated praise 4 times, for all his enemies are fallen, overthrown and slain. Horus the son of Isis and the son of Osiris has repeated millions of jubilees, for all his enemies are fallen, overthrown and slain. They have been carried off to the place of execution, the slaughtering-block of the easterners. They have been decapitated, they have been strangled, their arm(s) have been cut off, their heart(s) have been removed. They have been given (to the Great) Annihilator in the valley; they shall never escape … .”15

Egyptologists A.M. Blackman and H.W. Fairman recognize Horus as the god of war, who may have had a kernel of historical reality as a founder of Egypt:

“Junker has expressed the opinion, not without reason, that the god of Edfu, Horus of Behdet, was in his original form a warrior-god as well as a divine king, the stories of whose exploits rest ultimately on an historical basis. That basis, if we accept the theory propounded by Sethe in his Urgeschichte [prehistory], is to be found in the wars waged in pre-dynastic times by the Horus-kings of Heliopolis, whose frontier town was Edfu, against the Seth-kings of Ombos and southern Egypt.”16

B) Ham cf. Horus: (Earthy) blackness/darkness

An important word for ‘black’ in Egyptian is km (Wb 5, 124.10–12), and Egypt’s name km.t means “the black land” which refers to the black fertile Nile-flood soils (see part 2). From the discussion above, Egyptian ‘km’ and Hebrew ‘Ḥam’ share semantic concepts of ‘earthy blackness/darkness’. Here we have an immediately apparent link with the black earthiness inherent in Ham and Egypt’s names.

Horus the ‘very black’

Egyptologist T.G. Allen stated that “Horus is black and great (or ‘very black’) in his name of km-wr.”17 For instance:

PT-600§1657a–1658d.

(§1657a) ḥr.w … (§1658a) km.t wr.t m rn=k n(.j) ḥw.t-km-wr … (§1658d) ḥr.w

“Horus … .You are black and great/ very black in your name ‘House of the Great Black [Bull]’… Horus … .”

The French Egyptologist Émile Chassinat recognizes km-wr signifies Horus from a “very early stage”18 and that the black bull of Athribis was worshipped as the incarnation of Horus.19 For instance, an inscription engraved on the sarcophagus of the Apis bull, which died in the year 2 of Khabash (31st Dynasty pharaoh) is said to be: “Loved by Apis-Osiris and Horus the black bull.”18 Chassinat states: “The quality of ‘great black bull’ attributed in our ritual to the local Osiris, associates him with Horus in his bovine incarnation”20 (figure 4).

Horus is also described as dwelling in “darkness” (kk), for instance:

(18th Dyn.) pKairo G51189 (pJuja), Tb153.

ḥr.w {tw} pw ḥmsi(.w) wꜤi.yw m kk.w jw.tj mꜢꜢ=f

“That is Horus, sitting alone in the darkness, who cannot be seen…”

I will return to the significance of Horus epithets containing the root kk (in motif 3).

C) Sun’s heat: Horus cf. Ham

Genesis 8:22 “covenant of the seasons” uses ‘ḥōm’ to describe heat from the sun (thereby expanding the semantic range of Ham’s name to include concepts of the sun’s ‘heat’). Horus is fundamentally connected to the sun and heat, being worshipped from the earliest times as the solar deity RēꜤ-Ḥarakhti, (raw-ḥr.w-Ꜣḫ.tj)—a triple-epithet combining RēꜤ the ‘sun-god’, with ‘Horus’, who is ‘dwelling in the horizon’.

Egyptologist T.G. Allen states:

“The eye of Horus was further identified with the sun … Pyr. 698, either an instance of identification of Re and Horus or a further case of the eye assuming the place originally belonging to Horus himself.”21

For instance Pepis II PT-402§698d states:

(|ppy|)(|nfr-kꜢ-rꜤw|) pw jr.t tw n.t {ḥr.w} ‹raw› sḏr.t jj.t msi.t raw-nb.

“Pepi Neferkare is that Eye of {Horus} ‹Re› who is conceived and born at night, every day.”

Egyptologist S. Edwards points out that pyramid “T[eti] has the Eye of Re and N[eith] has the Eye of Horus”22 indicating Horus and Re were thought of as synonymous.

The flame and heat of Horus’s eye is particularly spelled out in MK CTs. For instance, CT-313:91:

“I am Horus, son of Osiris, born of the divine Isis. I am king in Chemmis, my face is formed as that of a divine falcon; I created my Eye in flame … .”23

Egyptologist R.L. Shonkwiler recognizes Horus’s connection by birth to the heat and flame of the sun, stating: “As the ‘solar child’, Horus is born in the Island of Fire after being conceived by flame.”24

A further epithet of Horus appears in OK PTs connecting him with “fiery breath” (Wb 1, 471.16) bḫḫ.w, for instance:

Unas PT-313§503a–503b.

… ḥr.w sp 2 sbn (|wnjs|) [j]m m bḫḫ.w pn ẖr jkn.t nṯr jri=śn wꜢ .t n (|wnjś|) śwꜢ (|wnjś|) jm=ś (|wnjś|) pj ḥr.w

“… Horus (twice) … Unas there in that glow of fire, under … the gods.

They pave a way for Unas so that Unas may pass on it.

Unas is (a) Horus.”

Furthermore, the phonetic root of ‘fiery glow’ bḫḫ.w (ḫḫ) is shared with an OK divine name jḫḫ.w “twilight” (Wb 1, 126.5) e.g. Teti PT-421§751b, demonstrating a phonetic link with kk root words (see motif 3).

Motif 2 summary

Like biblical Ham, Horus is synonymous with concepts of: A) (physical) “violence” (tkk); B) (earthy) “blackness” (km)/“darkness” (kk)/“twilight” jḫḫ.w; and C) (sun’s) “heat” (bḫḫ.w). The significance of the root kk is discussed in motif 3.

Motif 3. Family of eight—Horus cf. Ham

Genesis (6:18, etc.) informs us that Ham belonged to a family of eight—comprising four males and their wives. Ancient Egypt had a group of eight gods—comprising of four males and their wives (the Ogdoad) whose names (see later) appear in OK PTs. In previous articles,25 I concluded this group represented the paganized memory of Noah’s family. The question to be asked is, if Horus is the deified Ham, is he also connected to a family of eight? Evidence presented below suggests he was. Specifically, the Ogdoad, whose names include the couple Kek and Keket (kk and kk.t).11

Like the semantic meaning of Ham, as discussed above, Horus is also connected by similar concepts: “attacker” (tkk), “darkness/twilight” (kk, jḫḫ.w) and phonetically similar bḫḫ.w “heat”. Ogdoad kk can be understood semantically from words containing the phonetic root kk, (compare ḫḫ). Thus, a shared semantic range exists between biblical Ham, Horus, and Ogdoad couple kk(.t).

Additional textual and pictorial evidence connecting Horus to the Ogdoad comes from the BOD (figures 5–7).

Egyptologist E.A.W. Budge explains the context of Hunefer’s vignette from BOD chapter 17 (figure 5):

“The sunrise. Beneath the vaulted heaven stands a hawk [Horus], having upon his head a disk encircled by a serpent, emblematic of the sun-god … . Ra-Harmachis [sic]. On one side are three and on the other four apes, typifying the spirits of the dawn, who are changed into apes as soon as the sun has risen. The accompanying legends read: ‘Adoration to Ra when he riseth in the horizon. Adore thee the apes, Oh Ra-Harmachis’.”26

Further evidence comes from BOD (figure 6) which places Horus amongst the Ogdoad.

Egyptologist E.A.W. Budge gives the context of this vignette:

“… The mummy of Anhai [sic] lying on the top of the double staircase, which is in the city of Khemennu [Ogdoad city] … . Above are eight white disks [representing Khemennu/Ogdoad] on an azure ground … . The god Nu raising the boat which contains the beetle and Solar disk, and seven gods … .”27

One question to be asked here is the shape of the solar bark—it is not like that of Noah’s Ark—if indeed it represents it. The divine boat has a flat keel, distinctively high, curved prow, stern, and fixed rear oars. This specific shape will be discussed in part 2 (motif 10), and its dimensions (motif 6).

The eight gods and Horus

The ‘spirits of the dawn’ were typically eight baboons heralding the first sunrise—representing the Ogdoad. This is demonstrated beyond doubt from tomb wall inscription at the 26th Dynasty tomb of Ba-n-nentiu, Bahria Oasis. The image below (figure 7, lower register) shows the Ogdoad in simian form, worshipping Horus as the sun (in the top register), sailing the solar barge across the sky, attended by various deities.

The cartouches written above the Ogdoad read (from right to left): Nu, Nunet, Amun, Amunet, Hehet, Heh, Keket, Kek. The Ogdoad is also symbolized with a single baboon determinative,29 seen from evidence from the Great Hymn to Amun at Hibis temple. Egyptologist David Klozt explains:

“The baboons at Hibis address the newborn sun in epithets similar to those used in the Book of the Day, which is also present in the Solar Chapel of Medinet Habu. At the same time, the horizontal texts above the baboons are actually excerpts from the Great Amun hymn, an indication that these eight baboons are simultaneously understood as the Ogdoad. The Ogdoad are associated with Amun elsewhere only in the Small Temple of Medinet Habu, and their striking presence at Hibis suggests some relation between the theology of Medinet Habu and Hibis … .”

[footnote 68] “the column 0 of the Great Amun hymn … write ‘the Ogdoad’ with a baboon [ determinative].”30

The worshipping baboon determinative, in the BOD Hunefer vignette (figure 5) is accompanied by the hieroglyph htt, “Screamer” (Wb 2, 504.4-6) indicating the Ogdoad ( ). However, only seven baboons worship Horus Ra-Harakhty. It seems one of the Ogdoad members has become Horus. A passage from the CT supports this theory:

). However, only seven baboons worship Horus Ra-Harakhty. It seems one of the Ogdoad members has become Horus. A passage from the CT supports this theory:

CT-50:223–225

“The Followers have given hands to the Chaos-gods, Horus the Protector of his father is glad … . Horus, pre-eminent in Khem … to you there belongs one of the two Chaos-gods … .”31

I demonstrated previously that the Eight Chaos-gods are to be connected with the Ogdoad.32 The Chaos-gods came in pairs, here, one of the pair of Chaos-gods is described as “belonging to Horus”, which could well be kk—who represents primeval darkness. That being the case, kk’s ascent to the sun follows the natural course of dusk to dawn.

Motif 3 summary

As Ham came from Noah’s family of eight, Horus also comes from a group of eight gods.

Motif 4. Ham cf. Horus—three brothers

Scripture states Noah had three sons: Ham “his youngest” (Genesis 9:24) and “Shem … brother of Japheth the elder” (Genesis 10:21 YLT). Here Scripture employs the adjective: קָטָן (qāṭān) HALLOT-8338 ‘small, youngest’ to describe Ham. Can similar relationships be discerned in Horus’s family? The following evidence suggests this is so.

Horus is described in Pepis I PT-539§1320c as:

Hr.w nẖn(.w) ḫrd

“Horus, the little child.”

Horus had a notable brother called Seth, with whom he violently struggled (see motif 8), for instance:

Merenre PT-615§1742a.

jmi.y jr(.t)-ḥr.w ḥr ḏnḥ n.j sn=f stš

“Put the eye of Horus on his brother Seth’s wing.”

Also Pepis I-667a§1948b:

“[Horus will] be cleansed of what [his] brother [Seth] did to him, [Seth will be cleansed of what his brother Horus] [did] to him … Horus will be purified when he [embraces] his father Osiris.”

Another god, called Thoth is constantly associated with Horus and Seth in PTs, indeed, there is a clear overlap between Seth and Thoth as noted by Čermák,33 who also recognizes family relationships are often contradictory. Seth is brother to Horus, and yet simultaneously brother of Osiris in PT. However, Seth and Thoth are described as brothers together in:

Neith PT-218§163d.

m=k jri.t.n stš ḥna ḏḥw.tj sn

“See what Seth and Thoth have done, your brothers” (referencing Pharaoh Neith).

Neith PT-370–375.

ḫai.t (j) m bj.t (j) ḥr.w ḏḥw.tj snsn.w jr=k m sn bj.t (j) {ḥr.w} {ḏḥw.tj}

“You appeared as King of Lower Egypt and Horus and Thoth have joined you as the two brothers of the King of Lower Egypt” (referencing Pharaoh Neith).

The following (MK) Coffin Text makes clear the brotherhood of Horus, Seth, and Thoth: CT-681.

“O Thoth, son of the Harpooner, brother of Horus and Seth, who are on your throne, silence Seth.” (Faulkner 2004: II, 246).34

Čermák recognizes the role of Thoth in that the mythical fight between the two brothers Horus and Seth that he “pacifies the two fighters Horus and Seth, bringing to an end the archetype of discord in the world”35 (see motif 8).

And in the BOD, a TIP papyrus of Pennesuttawy (Egyptian Museum JE95881) makes Osiris the father of Thoth:

“Words spoken by Thoth, lord of the words of the god, writer of what is right for the Great Nine Gods, before his father Osiris lord of eternity [wsir nb ḥḥ].”36

Motif 4 summary

Horus had a brother, Seth, (both sons of Osiris) with whom he struggled violently for political dominion (see part 2, motif 8). A closely aligned god called Thoth is described as a brother of either Seth, or Horus in the PTs, and one example in the Coffin Texts of Horus, Seth, and Thoth being described as brothers. In BOD, Thoth shares the same father (Osiris) as Horus and Seth. When these examples are considered, then Horus is comparable to Ham in having two other brothers, and himself being described as the ‘youngest’.

Conclusion

This article has looked at four motifs from Ham’s life and compared them to Horus, the Egyptian falcon sun-deity. We have found positive connections in the following areas: motif 1. Ham was 11th from Adam. The case can be made that Horus is 11th from Atum when Osiris as the fatherly bystander is included from evidence in PTs regarding the Great Ennead. Motif 2. The etymology of Ham’s name includes concepts of (physical) “violence”, (earthy) “blackness/darkness”, and (sun’s) “heat”. These concepts compare favourably with divine epithets of Horus. Motif 3. Ham came from a family of 8—four males and their wives. The case is made here that Horus ascended from the Ogdoad, who are four males and their wives. Specifically, Horus is connected to Ogdoad member kk (darkness) in which case kk follows the natural ascension of darkness to light, to transform into Horus as the sun. Motif 4. Ham was the youngest of three brothers, Shem, and Japheth. The case can be made that Horus is the “child” who has a notable brother, Seth, and closely aligned to Thoth, another brother-(like) god. The connections are intriguing and so merit further study. Part 2 will analyze motifs 5–12.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Gary Bates and several anonymous reviewers for their critical remarks on earlier manuscripts.

References and notes

- See introduction in: Pinch, G., Handbook of Egyptian Mythology, ABC-Clio, CA, pp. 143–147, 2002. Return to text.

- creation.com/timeline. Return to text.

- Cox, G., In search of Adam, Eve and creation in Ancient Egypt, J. Creation 35(1):61–69, 2021. Return to text.

- Klotz, D., Adoration of the Ram: Five hymns to Amun-Re from Hibis Temple, Yale Egyptological Seminar, CT, p. 118, 2006. Return to text.

- Ryholt, K., The Turin King List, Ägypten und Levante 14:135–155, 2004; p. 139. Return to text.

- Waddell, W.G., Manetho, Harvard University Press, London, p. 3, 1964. Return to text.

- Waddell, ref. 6, p. 5. Return to text.

- Cox, G., The search for Noah and the Flood in ancient Egypt—part 3, J. Creation 34(2):67–74, 2020. Return to text.

- Garsiel, M., Biblical Names: A literary study of midrashic derivations and puns, Graph Press, Jerusalem, p. 86, 1991. Return to text.

- Cassuto, U., A commentary on the book of Genesis II, Verda Books, IL, p. 234, 2005. Return to text.

- Cox, ref. 8, p. 71. Return to text.

- Loprieno, A., Ancient Egyptian: A linguistic introduction, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, p. 35, 1995. Return to text.

- Loprieno, ref. 12, p. 42. Return to text.

- Hoch, J.E., Semitic Words in Egyptian Texts of the New Kingdom and Third Intermediate Period, Princeton University Press, NJ, pp. 230, 456 ̶ 520, 1994. Return to text.

- Allen, T.G., The Egyptian Book of the Dead, University of Chicago Press, IL, p. 35, 1960. Return to text.

- Blackman, A.M. and Fairman, H.W., The Myth of Horus at Edfu- II, J. Egyptian Archaeology, 28:32–38, 1942; p. 32. Return to text.

- Allen, T.G., Horus in the Pyramid Texts, Ph.D. dissertation, University of Chicago, Chicago, p. 27, 1916. Return to text.

- Chassinat, E., Le Mystère D’osiris au Mois de Khoiak, Le Caire Imprimerie de L’institut Français D’archéologie Orientale, (translated from original French.), p. 182, 1966. Return to text.

- Chassinat, ref. 18, p. 175. Return to text.

- Chassinat, ref. 18, p. 183. Return to text.

- Allen, ref. 17, p. 13. Return to text.

- Edwards, S., The symbolism of the eye of Horus in the Pyramid Texts, Ph.D. thesis, University College of Swansea, p. 137, 1995. Return to text.

- Faulkner, R.O., The Ancient Egyptian Coffin Texts, vol. I, Spells 1–354, Aris & Phillips, Warminster, p. 234, 1973; also CT-205:145; 249:343; 316:98. Return to text.

- Shonkwiler, R.L., The Behdetite: A study of Horus the Behdetite from the Old Kingdom to the conquest of Alexander, Ph.D. thesis, University of Chicago, IL, p. 413, 2014. Return to text.

- Cox, G., The search for Noah and the Flood in ancient Egypt: part 1 and part 2, J. Creation 33(3):94–108, 2019. Return to text.

- Budge, E.A.W., Facsimiles of the papyri of Hunefer, Ankhai, Kērasher and Netchemet, Longmans and Co., Oxford, p. 4, 1899. Return to text.

- Budge, ref. 26, p. v, plate 8. Return to text.

- Fakhry, A., The Egyptian deserts—Bahria Oasis, Cairo Gov. Press, Bulâq, p. 75, 1942. Return to text.

- Fakhry, ref. 28, p. 77; example from temple of Kharga. Return to text.

- Klozt, D., Adoration of the Ram: Five hymns to Amun-Re from Hibis Temple, Yale Egyptological Seminar, New Haven, CT, p. 10, 2006. Return to text.

- Faulkner, ref. 23, p. 47. Return to text.

- Cox, ref. 25, p. 99. Return to text.

- Čermák, M., Thoth in the Pyramid Texts, Ph.D. thesis, Univerzita Karlova v Praze, Filozofická fakulta, Ústav filosofie a religionistiky, pp. 22, 62, 2015. Return to text.

- Faulkner, R.O., The Ancient Egyptian Coffin Texts, vol. II, Warminster, Aris and Phillips, 1977. Return to text.

- Čermák, ref 33, p. 75. Return to text.

- Quirk, S., Going out in Daylight—prt m hrw, Golden House Publications, Croydon, UK, p. 515, 2013. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.