Feedback archive → Feedback 2022

Exodus evidence revisited

Tim L. from the US submitted the following.

I recently came across this article critiquing the Patterns of Evidence documentary: “Patterns of Poor Research - A Critique of Patterns of Evidence: Exodus” by Hector Avalos on the [site deleted per feedback rules] blog. I recognize CMI does not completely endorse the Patterns of Evidence position on Egyptian history, not to mention Rohl’s, but I’m wondering how much of the critique is valid, and how much isn’t. For example, he argues against the use of the Brooklyn Papyrus to show Hebrews were in Egypt, the identification of Joseph’s tomb, and the use of The Admonitions of Ipuwer to corroborate the Ten Plagues, which your review of the documentary mentioned favorably.

Your article on the Egyptian Chronology essentially agrees with the atheist that there is no evidence of the Exodus, but argues (I think somewhat legitimately) that we shouldn’t expect any. Does Avalos make valid arguments against the documentary, or are the evidences mentioned in your review stronger than he thinks?

Hi Tim,

I do not think there is enough evidence to demonstrate that there was an Exodus totally apart from the Bible, but neither do I think the evidence we have shows that the Exodus is implausible, let alone disproven. There are other possibilities in between these extremes. We can point to some circumstantial evidence broadly consistent with the Exodus, but keep in mind that what one considers evidence depends greatly on the particular alignment of Egyptian and biblical history to which one subscribes. I would certainly avoid saying there is “no evidence” for the Exodus, and I don’t think we have said such a thing in previous articles. (We have several articles about Egyptian chronology, so I’m unsure of the one to which you are referring.) Perhaps what you meant is that we have said it is very unlikely the Egyptians would publicize such a humiliating defeat by explicitly referencing the Exodus on their stone monuments. This is particularly true given that so many of these monuments exalt their pharaohs and their gods, whom the plagues were specifically directed against (Exodus 12:12). But while there is no explicit evidence of the Egyptians acknowledging these events, there are arguably more subtle forms of evidence supporting the Exodus.

I read the piece by Avalos and, while I cannot respond to everything in depth, I’ll address some of the points he raised. In general, I thought some of his critiques seemed credible and I am inclined to agree with them (though I did not fact check every detail), but other criticisms he made depend on false or overly simplistic assumptions.

Date of the Exodus

Avalos prefers the ‘late date’ for the Exodus (in the 1200s BC, conventionally the time of Rameses II), as opposed to the ‘early date’ (c. 1446 BC). But his reasoning is rather flimsy. Many presume the pharaoh of the Exodus must have been a Ramesside king (and hence they adhere to a late date) because the Bible says that the Hebrews built the store cities of Pithom and Rameses (Exodus 1:11; cf. Exodus 12:37; Numbers 33:3). They point out that the latter site was likely named after Rameses II, and that construction occurred there during his reign. Or, at least, the city was named for one of the Ramesside kings, the first of whom (Rameses I) founded the 19th Dynasty. However, there are multiple ways we can account for the term ‘Rameses’ in Exodus 1:11 which do not require a late Exodus. See Case Study: Rameses.

One possibility is that, since the name of this site changed over time (it was previously known as Avaris and went by other names in other periods), scribes may have updated the name in the Scriptural text as well, so later readers would still be able to identify the city to which the text referred. This is not inconsistent with biblical inspiration since there are other clear examples where this happened. A robust concept of inspiration must include the Holy Spirit’s oversight of such textual updating. Genesis 14:14, for instance, mentions Abraham traveling to the city of Dan in order to rescue Lot. Yet the city of Dan was not yet called Dan in either Abraham’s time or the time of Moses, who wrote Genesis. The city was formerly called Laish and was not renamed by the tribe of Dan until the period of the Judges, as the Bible itself tells us (Judges 18:29). So the name of the city in Genesis 14:14 was updated well after the time of Moses.

In fact, the same thing occurs with the city of Rameses even prior to the events in the book of Exodus. Genesis 47:11 says:

Then Joseph settled his father and his brothers and gave them a possession in the land of Egypt, in the best of the land, in the land of Rameses, as Pharaoh had commanded.

If we followed the logic of the late-Exodus arguments, then even Joseph and Jacob would have to be situated in the 19th Dynasty, which no one believes. Rather, Joseph and family settled in the location that later came to be called Rameses, and the city name in this verse was updated to reflect that.

By contrast with the weak basis for locating the Exodus in the 19th Dynasty, there are many mutually-reinforcing biblical reasons to prefer the early date, as we’ve explained in our and in various web articles, including To give just one example, 1 Kings 6:1 seems pretty straightforward, which says the Exodus took place 480 years before Solomon began construction on the temple. This puts the Exodus in the middle of the 15th century BC, around 1446.

Correlating Joshua and Jericho

Avalos subscribes to the conventional view that Jericho was destroyed in 1550 BC, and that it lay abandoned in the time of Joshua (c. 1406 BC using the early Exodus date, or something like 1230 BC using the late Exodus date). He correctly says that the Patterns of Evidence film suggests shifting Egyptian chronology to produce a better alignment here. But there is another possibility—the destruction of Jericho has been misdated because of flawed argumentation. Our article explains why Jericho’s destruction should be dated to c. 1400 BC after all, without requiring a radical shift in mainstream chronology back to this point in time. The conventional date is in serious error mainly due to the faulty carbon-14 dating of the site and the uncritical acceptance of Kathleen Kenyon’s pottery analysis, which has since been shown to be mistaken.

Brooklyn Papyrus

The document Papyrus Brooklyn 35.1446 contains the names of various household slaves, including many Semitic ones, and this portion of the text is thought to date to the 13th Dynasty of Egypt. The revised chronology of David Rohl has the Exodus taking place at the end of the 13th Dynasty, in which case this document could describe the time of the oppression. But a more conventional chronology would mean this text was written long before the Exodus, and maybe even before the Israelites were in Egypt (depending on the exact date of the composition, and whether one adopts a ‘long’ sojourn view of 430 years or a ‘short’ sojourn view of 215 years). For this controversial question, see How long were the Israelites in Egypt? and A response to a long Sojourn advocate.

I and a number of others at CMI do not subscribe to Rohl’s revised chronology as it actually (arguably) undermines many compelling and widely accepted synchronisms between the Bible and the archaeological remains.1 Therefore, I do not think this Brooklyn Papyrus has direct relevance to the Exodus. The document also comes from Thebes, which is well south of the Nile Delta where we know the Israelites lived from the start to the end of their sojourn (cf. Genesis 47:11; Exodus 1:11; 12:37). Still, it may be closer to the time of Joseph and show at the very least that there were Semitic slaves in Egypt around the same time Joseph was a slave. This document also mentions prisons in Egypt, consistent with Joseph’s experience, and that some slaves had the title “he who is over the house” which matches Joseph’s position under Potiphar (Genesis 39:4).

Avalos emphasizes that Semitic speaking peoples are a much broader group that includes many others besides the Israelites, and hence the slaves listed are unlikely to be Israelites specifically. I do not know enough about linguistics to evaluate all that Avalos says here, but some of the names used are very close to names used in the Bible. The name Shiphrah appears, which is one of the Hebrew midwives mentioned in Exodus 1:15. Also, there seem to be feminine equivalents of the names Issachar, Asher, Jacob, Menahem, and compound names that incorporate the names David and Eve.

Avalos says that these are cognates to biblical names, not identical to them. Assuming he is correct, I don’t know whether his point is significant or nit-picky. He also tries to argue that these cannot be Israelites since some of the theophoric names refer to pagan deities like Anat, Baal, and Resheph, rather than Yahweh. However, this argument does not seem definitive to me since, in the Bible, compound names that referred to Yahweh (e.g., Isaiah, Joel) were more common in the later divided kingdom period, while in the early centuries of Israel it was more common for an individual to be named after pagan gods. Saul’s son, for example, was named Eshbaal (Man of Baal; 1 Chronicles 8:33), though the biblical writers intentionally changed it to Ish-bosheth (Man of Shame; 2 Samuel 2:10) for obvious rhetorical reasons. Similarly, Jonathan’s son was named Merib-baal (From the Mouth of Baal; 1 Chronicles 8:34), and alternately Mephibosheth (From the Mouth of Shame; 2 Samuel 4:4). Gideon also was given a second name, Jerubbaal (Let Baal Contend). This name was likewise cleansed of pagan elements in 2 Samuel 11:21, where it appears as Jerubbesheth (Let Shame Contend). Incidentally, thanks to relatively recent discoveries, the names Eshbaal and Jerubbaal are both attested in the archaeological record, in roughly the same time periods as their biblical counterparts.

Avalos further claims that there is “no attestation of a distinctive Hebrew language until about the tenth century BCE.” This claim was engaged in the second Patterns film, called The Moses Controversy (which we reviewed). Again, I do not have the expertise to evaluate whether the early alphabetic inscriptions should be considered Hebrew proper or merely some other related or ancestral Semitic language, but suffice to say that Avalos’ claim here has been disputed by some. It may also be relevant that the recently recovered curse tablet from Mount Ebal has an inscription which the discoverers date to between 1400–1200 BC, and the writing may require a reevaluation of how and when Hebrew script developed. [Update, 4 December 2023: This interpretation of the lead 'curse tablet' has been challenged, since it appears very similar to ancient lead fishing weights, and it is an debated issue whether the markings have been rightly interpreted as writing.] Likewise, the Lachish ostracon we touched on in Creation magazine may have similar implications.

Jacob and Joseph found at Avaris?

The Patterns movie helped to popularize Rohl’s perspective that specific houses and tombs in Avaris (which later became the site of Pi-Rameses) can be connected to Jacob, Joseph, and the rest of their family. I am inclined to agree with Avalos here that the evidence for this is pretty weak, even though we at CMI do think that Avaris is the location where the Hebrews lived, perhaps beginning at a slightly later time, through the Hyksos period and on into the 18th Dynasty. I could even add a few things to Avalos’ critique, like the fact that the oversized statue of the Asiatic official (which Rohl identifies as Joseph) is not unique. In a museum in Munich, there is another statue head with a similar mushroom-shaped haircut. This one also came from Avaris, so I suppose one could also argue that it, too, represents Joseph. But it could also simply be the case that this area was beginning to be heavily populated by Asiatics in this time period and thus it would not be out of the ordinary that some of them rose to positions of prominence.

Surprisingly, however, others who reject Rohl’s revised chronology have also argued for an association of these finds with Jacob and Joseph. Bryant Wood, for instance, puts the Exodus in the 18th Dynasty of Egypt (as CMI is inclined to do, unlike Rohl), but he subscribes to a long sojourn, which means he has Jacob moving to Egypt in 1876 BC, during Egypt’s 12th Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom.2 Some of us at CMI have offered arguments that Joseph rose to power later, perhaps in the Second Intermediate Period. Among these arguments are the fact that chariots didn’t become really prominent until after the Middle Kingdom transitioned to the Second Intermediate Period, and Joseph rode in one of Egypt’s chariots according to Genesis 41:43. (Follow the link, but this is also discussed further in our Tour Egypt booklet). This may fit better with an Exodus in the 18th Dynasty and a short sojourn of 215 years preceding this. On this reconstruction, the statue at Avaris from the 1800’s (according to the conventional dates) is too early to be Joseph.

Tenth plague and the abandonment of Avaris

Avalos points out that the date traditionally assigned to the end of the stratum Rohl wants to associate with the Exodus departure is about 1710 BC, not 1450 BC, and he chides the Patterns film for not mentioning this. But I’m not sure whether Avalos, by issuing this challenge, has forgotten that Rohl maintains the entire chronology of Egypt should be shifted by this much. He’s not just arguing for an expansion of time in particular strata.

However, if Avalos is correct that there is little evidence for a catastrophic loss of life at this juncture, this is no trouble to me as, again, this is too early to be associated with the Exodus in my view. Doug Petrovich has argued that there is also an abandonment at Avaris that occurs in the 18th Dynasty, during the reign of Amenhotep II, who is a viable candidate to be the pharaoh of the Exodus.3 We have made this same suggestion in our Tour Egypt booklet.

Admonitions of an Egyptian Sage (Ipuwer papyrus)

This document describes a dark time in Egypt from the perspective of a famous Egyptian sage. Many historians say it belongs to a genre of literature prominent in Egypt’s Middle Kingdom, which lamented the social chaos of the time (or possibly some previous era) through the use of cliches and other motifs that should not be understood as historical reportage. But some, like Rohl, see the disastrous situations described in this text as the aftermath of the historical biblical plagues. One can understand why the comparison with the Exodus account is made, since Ipuwer at one point says of the Nile, “The river is blood!” It also refers to the ubiquity of death in the land, and the transfer of wealth from upper classes to the poor and the slave, reminiscent of the Israelites plundering the Egyptians.

Perhaps the best case that Ipuwer should be connected to the plagues has been made recently by Titus Kennedy in an article in Bible and Spade, published by our friends at the Associates for Biblical Research.4 Kennedy discusses the date of this text (distinguishing between the date of the manuscript copy itself, the composition of the text, and the period described by the text). He presents several lines of evidence that the document may have been composed in the 18th Dynasty. If correct, this would not support Rohl’s perspective, and would be more consistent with an Exodus in the 18th Dynasty, the view that Kennedy holds. I won’t venture to evaluate these arguments about the composition date, but you can track down the article if you want to learn about them.

Kennedy also offers some reasonable pushback against the point Avalos makes about the events being in a different order when one compares Ipuwer to the book of Exodus, and also the point others have made that not all the plagues can be identified in Ipuwer. Kennedy says the biblical psalms clearly refer to the plagues, but do not present them in chronological order, and they are likewise selective—only referring to some plagues but not all. So this lack of precise correspondence between Ipuwer and the book of Exodus need not disqualify the view that it could be describing fallout from the plagues.

However, even if we grant that Ipuwer could have been written around the time of the Exodus, there are reasons to think this text is describing something unrelated to the biblical events. One should not cherry pick the parts that sound most similar to the Exodus account and ignore the parts that fail to match. For example, much of the text describes role reversals, as mentioned above, where the lower classes usurp the domains of the upper classes. But several of these are clearly not descriptions of Israelites plundering the Egyptians. Consider these lines from Ipuwer:

Behold, he who could not build a boat for himself is now the possessor of a fleet;

Behold, he who had no grain is now the owner of granaries, and he who had to fetch loan-corn for himself is now one who issues it.5

This cannot be describing the Israelites since they surely did not acquire and operate granaries and boats on their way out of Egypt. Such things could not be carried off through the Red Sea and on to Mount Sinai. Plus, if the plagues afflicted all of Egypt (rich and poor alike, cf. Exodus 11:5), then why does Ipuwer not describe a more universal devastation rather than the elevation of these lower classes? Additionally, we have suggested that Egypt and pharaoh’s army need not have been as completely devastated as is commonly thought. See Was Egypt completely destroyed by the events of the Exodus?

I agree with Avalos that many of Ipuwer’s descriptions of disastrous circumstances are relatively vague and could apply to many situations and time periods. I also agree that similar laments appear in other ancient documents unrelated to the Exodus. The striking statement about the Nile being blood is the most convincing parallel, yet it seems to me that even this could result from mere coincidence. More surprising coincidences have occurred, such as in the fictional book Futility, written about a ship called the Titan which struck an iceberg in April in the North Atlantic on its maiden voyage, and sank despite not being equipped with enough lifeboats for all its passengers. These details also became true of the historical ship, the Titanic, in 1912, but the book about the fictional ship was first published in 1898, fourteen years earlier.

To me, it does not seem terribly surprising that the Nile would be described as ‘blood’ in a time marked by death and national disaster, since the Egyptians associated the Nile with life, and blood is a term that in this context represents death. If the annual Nile flood did not occur, say, in a particular year, the life-giving silt that was usually deposited would mean less arable land for planting and reaping. And subsequent low river levels would have left the water dirty and possibly stagnant in some areas etc. The effects of this would be devastating for a nation that relied so much on this annual event to irrigate its crops and feed its people.

Avalos may also be correct when he argues that Ipuwer speaks of the Nile as blood because earlier it says dead bodies were being tossed in the river. Perhaps it was filled with literal blood in that sense, or perhaps the dead bodies contaminated the water and to drink of it produced ill effects or even death.

It’s true that our review of Patterns of Evidence: Exodus says the Ipuwer Papyrus “might support the biblical account”, but this isn’t a particularly strong endorsement. To temper this, we have also previously published the views of Adamthwaite and Clarke (see sidebar and comments) on this subject who, though they argue for significant chronological revisions of Egyptian history, both caution against using Ipuwer as evidence for the Exodus.

Amarna letters

The Amarna letters are a corpus of clay tablets which contain correspondence between Canaan/Syria and Egypt in the 1300s BC. In these texts, the rulers of various cities in Canaan and Syria complained about their troubles and sought the help of the Egyptian pharaohs to whom they were subservient, but their cries for help mostly fell on deaf ears. These pharaohs were Amenhotep III and his son Akhenaten, who ruled in the latter half of the 18th Dynasty.

Avalos says the Amarna letters undercut the possibility of a conquest in c. 1400 BC, since they lend no credence to Israel occupying Canaanite cities after the turn of the century. Assuming the conventional chronology, however, some of these letters may have been written around the same time the conquest was taking place, and/or spanned the time shortly afterward. Some scholars argue that there is in fact a nice correspondence between the circumstances described in these documents and the events recorded in Joshua and Judges. For example, the letters reveal that the Canaanite rulers were frequently under attack from peoples they called ‘Apiru (which seems to refer to rebels/outlaws on the outskirts of society). This is not a term that refers exclusively to Israelites, but could have been a term applied to them in many cases. Also, these letters show that Egypt’s influence in Canaan was diminishing at this time, compared to pharaohs earlier in the 18th Dynasty. Amenhotep III and Akhenaten basically ignored the pleas for help from their Canaanite vassals. This fits nicely with the record in Joshua and Judges that Egypt was not an impediment to the Israelites entering the land. (Check out our latest Creation.com Talk podcast episode, Can we align Egyptian history and the Bible?, that discusses this subject as well.)

Moreover, the Bible presents a more complex picture of the conquest than a lightning-fast invasion and permanent takeover of the whole promised land. Many of the places Joshua defeated were not occupied by the Israelites, but left abandoned, allowing indigenous peoples of Canaan to move back in, including apparently Hazor. For a number of these cities, such as Megiddo, Gezer, and Jerusalem, Joshua’s army killed their kings, but the books of Joshua and Judges also consistently state that Israel failed to drive out the inhabitants of these cities completely. These same cities appear in the Amarna letters as those still under Canaanite authorities, so there is actually a nice harmony between the two sets of records.

I do think, though, that Avalos is more on target when he cites the Amarna letters as a problem specifically for Rohl’s revised chronology. Rohl’s revision places the Amarna letters in the time of King Saul, but by then the descriptions of circumstances on the ground in the land of Israel seem to be mismatched with the Amarna letters. Bryant Wood has also criticized Rohl on this very point, in an article worth reading.6 In my view, Rohl’s chronological revision here destroys other strong synchronisms between the Bible and the archaeological evidence, like the migration of the tribe of Dan up to the city of Laish before there was a king in Israel (Judges 18). Excavations at Tel Dan found a destruction event in the right time period, followed by new occupants with a new culture—a people who migrated from the south. But Rohl’s revisions would undermine this chronological connection.

Positive evidence for the Exodus

Lest one think the case for the Exodus all hangs on a David-Rohl-style revisionist perspective, here are a number of points I see as supportive of the Exodus (and the biblical record describing it) that need not adopt his approach. These are all consistent with the Exodus having taken place in the 18th Dynasty of Egypt, while some points might also fit other proposals. These are in addition to the few positive evidences I’ve already mentioned above.

- Moses, which sounds like “draw out” in Hebrew (Exodus 2:10), is nevertheless likely derived from an Egyptian root msy (meaning “to give birth”). Perhaps it is no coincidence that Moses fits into the timeframe of the Thutmosid (18th) Dynasty, in which many of the pharaohs and other Egyptian officials also had the element msy incorporated into their names (Ahmose, Ptahmose, Ramose, and four kings called Thutmoses). This phenomenon does extend past the 18th Dynasty into the rest of the New Kingdom as well, with pharaohs such as Amenmesse and Rameses, for example.

- Many of the objects Israel used in worship or in battle seem to be well situated in this time period, since we have analogues in Egyptian or other ancient Near Eastern cultures. For example, Israel had silver trumpets (Numbers 10:2) which are also depicted in Hatshepsut’s 18th Dynasty mortuary temple. The Egyptians had wooden chests of religious significance, carried by permanently attached poles, such as the one in the tomb of Tutankhamun—reminiscent of the Ark of the Covenant.

- The Bible indicates that Jacob’s family moved to the land of Goshen in the eastern Nile delta, and rapidly increased in numbers. In the Nile delta for centuries leading up into the 18th Dynasty, we find Asiatics (peoples from the region of Canaan) present and growing in population size.

- The Israelites are said specifically to have built the store cities of Pithom and Rameses (Exodus 1:11; see earlier). At Pi-Rameses (formerly known as Avaris, among other names), there was occupation by Asiatic shepherds. There was also a 13-acre royal compound with three palaces built early in the 18th Dynasty, where Moses could have met with pharaoh. There seems to have been an abandonment of this site and these palaces in the 18th Dynasty. Pithom has not been identified with absolute certainty, but the most likely candidate site seems to be Tell el-Retaba. Until recently, this presented a difficulty since occupation during the 18th Dynasty had not been found there. But recent excavations have uncovered Semitic shepherds present at that time, along with mudbrick storage silos, and infant burial practices that differed from contemporary Canaanite customs. This site also experienced an abandonment in the 18th Dynasty during the reign of Amenhotep II and was not reoccupied for over 100 years.7

- The oldest reference to the name of Israel’s God, Yahweh, is found in an Egyptian temple at a place called Soleb in the Sudan (ancient Cush), south of Egypt. This was a temple built by Amenhotep III, a pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty mentioned already, and possible grandson of the pharaoh of the Exodus. It dates to sometime in the first half of the 14th century BC, so perhaps shortly after the Israelite conquest of Canaan took place. The broken pillars of this temple showcase a number of subdued enemies of Egypt, including one with an accompanying inscription that names the enemy as “the land of the nomads of Yahweh”. Why does the name Yahweh appear in an Egyptian temple in the 18th Dynasty before it shows up anywhere else? Perhaps it is because the nation of Israel was birthed in Egypt not long before this time.

- Though mainstream archaeology largely scoffs at the reliability of the biblical record of the conquest of Canaan, there is much archaeological evidence that is supportive of the conquest when properly interpreted. I discussed Jericho above, but there is also evidence from other cities Joshua conquered like Ai and Hazor. Even the Transjordan conquest that took place before Moses’ death has some support from Egyptian records in the 18th Dynasty, such as the series of reliefs by Thutmoses III at Karnak called the Palestine List. These inscriptions list Transjordan sites like Iyyim, Dibon, Abel-Shittim, Edrei, and Ashtaroth—places the Bible says the Israelites encamped or conquered. This shows that these locations did exist at the time Israel marched through the land, even though archaeological digs have yet to find occupation at some of the sites themselves.8 So, given that the Israelites did genuinely conquer the promised land as outsiders, this indirectly supports the Exodus since they had to come from somewhere, and the reliability of one debated part of the biblical tradition ought to bolster confidence in the other parts.

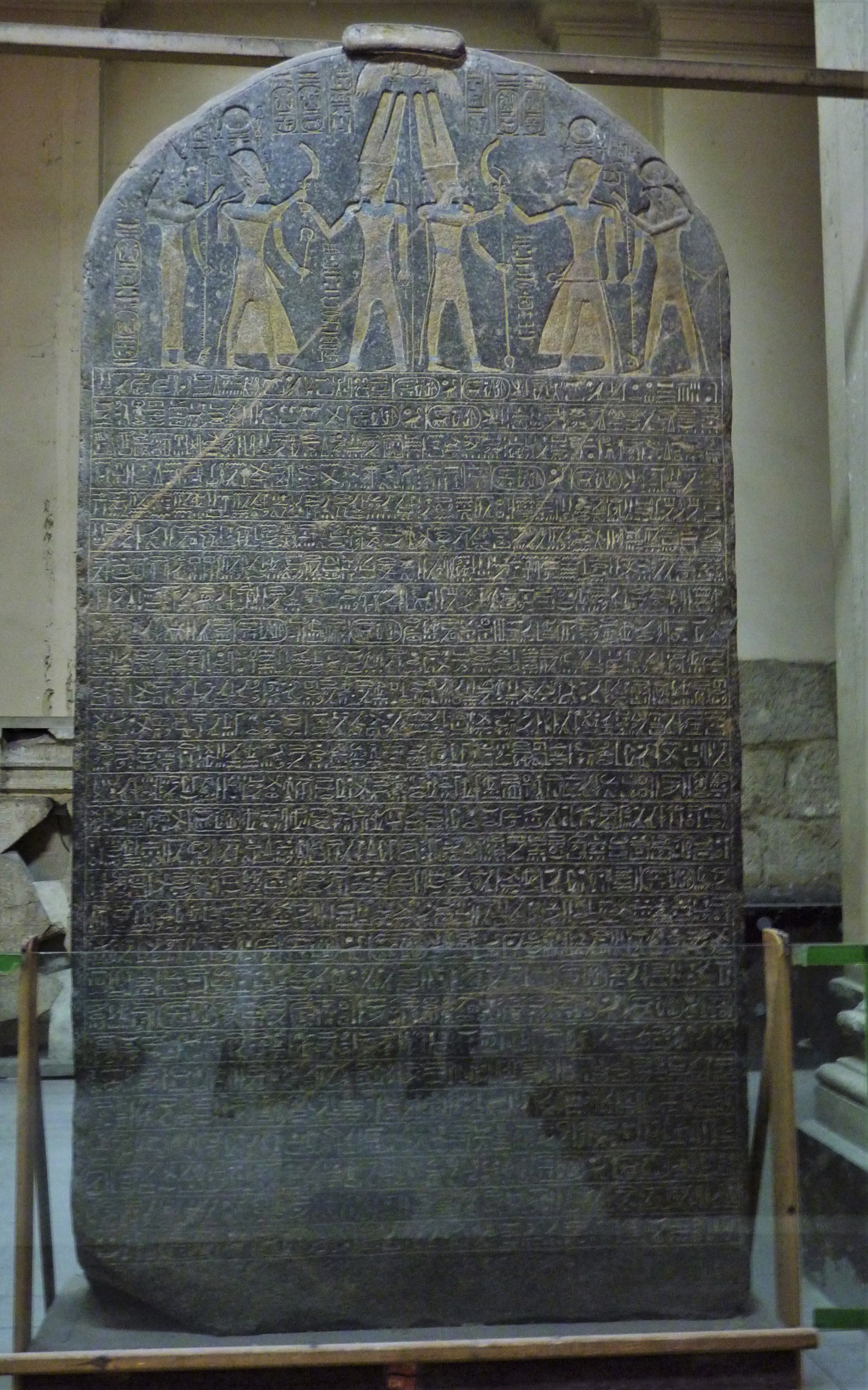

- The Merneptah Stela also lends support to an early Exodus in the 18th Dynasty. This stone slab was erected by Pharaoh Merneptah, the son of Rameses II, in about 1210 BC. It gives us the earliest clear reference to the name ‘Israel’, and it indicates this people group was already a powerful force in the land of Canaan by this time. They were a significant enough threat to Egypt that Merneptah boasted about having destroyed them, and they seem to be paralleled in the text with all of Syria-Canaan, indicating they had widespread control of the land. These considerations suggest the Israelites had already been established in this land for some time, not newcomers who had just arrived. So, working backward from the date of the Merneptah Stela to the Exodus, one would have to add in the length of time Israel was settled in the land, plus the roughly 6 years it took for Joshua’s conquest, and then another 40 years of wilderness wandering. The timing would have to be really tight to allow Rameses II to be the pharaoh of the Exodus, especially if one thinks the Israelites were building the city of Rameses early in his reign before the Exodus took place. But if the Exodus occurred in the previous (18th) dynasty, then Merneptah attacked Israel well into the time of the Judges, where there is a more comfortable match between Merneptah’s characterization of Israel and that found in the book of Judges.

- There are a variety of covenants in the first six books of the Bible that follow formats similar to other ancient Near Eastern treaties. The entire book of Deuteronomy, for example, is organized in a way similar to Hittite suzerain-vassal treaties. Oaths that appear in the books of Exodus and Joshua parallel Hittite treaties dated from 1600–1400 BC.9 This suggests these books were not written centuries after these events took place, but were written by people living at or near the time of the events they describe. It’s an indication their records are reliably grounded in the historical settings they purport to discuss.

- Finally, some scholars have argued that the very existence of a Passover tradition points to the truth of the Exodus. Why would anyone invent this history if it never really happened? The Exodus narrative doesn’t glorify the people of Israel. They were involved in humiliating slavery and lacked trust in God and his deliverer, Moses. It seems unlikely that this story would have been invented and become the origin account for the nation of Israel, unless it really happened.

This response isn’t meant to cover everything, but hopefully the discussion has helped you to better understand some of the different perspectives on the Exodus, and to weigh the evidence for yourself. Blessings as you continue to study and think through these things.

References and notes

- See, for example, Wood, B., David Rohl’s revised chronology: a view from Palestine, Bible and Spade, Summer 2001. Return to text.

- Wood, B., New evidence for Israel’s sojourn in Egypt, Bible and Spade 33(1):10–15, 2020. Return to text.

- Petrovich, D., Toward pinpointing the timing of the Egyptian abandonment of Avaris during the middle of the 18th Dynasty, Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections 5(2):9–28, 2013. Return to text.

- Kennedy, T., Ipuwer vs. the Exodus plagues, Bible and Spade 35(1):23–32, 2022. Return to text.

- Mark, J.J., The Admonitions of Ipuwer, World History Encyclopedia, 2016, worldhistory.org. Return to text.

- See ref. 1. Return to text.

- Kennedy, T., Pithom and the Exodus: New Discoveries, APXAIOC Newsletter #34, November 2021. Return to text.

- Wood, B., New light on the ‘forgotten’ conquest, April 2011, biblearchaeology.org. Return to text.

- Wood, B., The rise and fall of the 13th century Exodus–conquest theory, JETS 48(3):475–489, 2005. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.