Feedback archive → Feedback 2019

Doubt and the Cambrian explosion

Does lengthening the ‘timeframe’ of the Cambrian explosion make it easier for evolutionists to explain?

Gage C. from the United States writes:

Dear CMI,

I’ve recently been going through a time of doubt and during my search for answers I’ve hit something of a stumbling block. I’ve come across a number of articles written in the past 4–5 years describing the Cambrian Explosion as having occurred over the course of about 25–55 million years. The suggesting being that the developments seen are compatible with an evolutionary time scale as there is plenty of time for life to develop into newer forms. This question is furthered by the claim that many of the fossils found show a steady change linking back to a common ancestor. I’m sorry if my question has been answered by one of your prior articles, but I could not find anything addressing these claims. I don’t know how to respond to those who say our arguments have been “long refuted.” I look forward to your response and hope to see a day when we are no looked down on for our beliefs.

CMI’s Shaun Doyle responds:

What if the ‘Cambrian explosion’ were longer?

First, it might help to make sure that you properly understand what the ‘Cambrian explosion’ really is. It’s not simply an explosion of diverse lifeforms within a few million years. Rather, it’s the ‘sudden’ (with c. 10–25 million years in evolutionary thinking) appearance of a couple of dozen disparate, phylum-level bodyplans. As Dominic Statham explains in The Cambrian explosion:

Animals with fundamentally different body plans are said to be ‘disparate’ rather than just ‘diverse’. For example, while different members of the cat family (e.g., lions, tigers, leopards, domestic cats) are said to show diversity, different phyla (e.g. chordates, arthropods) are said to show disparity. Cats are all chordates, having a backbone and an internal skeleton. The differences between their anatomies are relatively minor. Arthropods (e.g. lobsters, crabs, insects) have no backbone and have an external skeleton. Their anatomies are fundamentally different to those of chordates.

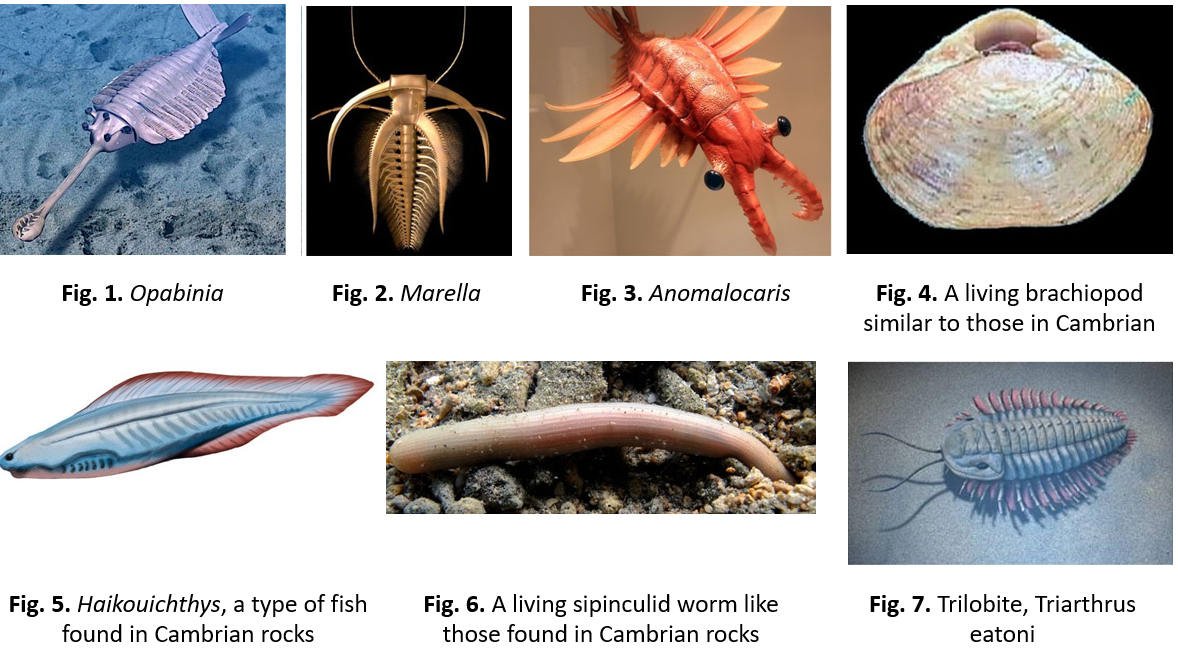

Some of the remarkably different forms that appear include Opabinia (figure 1), Marella (figure 2), Anomalocaris (figure 3), shellfish (figure 4), jellyfish, starfish, finned fish (figure 5) and worms (figure 6), and the extinct trilobites (figure 7).

Evolution predicts that diversity precedes disparity; a population splits into different species, which then further splits into genera, and then eventually into families, orders, classes and phyla. In other words, disparity should grow with time (especially as many ‘branches’ of the evolutionary tree die off). However, in the fossils, the opposite is true for animals; disparity precedes diversity. Most of the phylum-level disparity appears very abruptly and almost entirely in the Cambrian. Above that, diversity grows within phyla (and lower forms of disparity arise e.g. at class and order levels), but we almost never see new phyla arising. Evolutionary paleontologists Douglas Irwin and James Valentine make this point in their 2013 book The Cambrian Explosion: The Construction of Animal Biodiversity (see The Cambrian explosion in colorful, zoological context):

“Morphologic evolution is commonly depicted with lineages more or less gradually diverging from their common ancestor. New features arise along the evolving lineages, and diversification turns those features into synapomorphies of new clades while new apomorphies appear among the morphologically diverging branches. Gould (1989, 38) characterized this pattern as the ‘cone of increasing diversity’, but neither the fauna of the Cambrian nor the living marine fauna display this pattern. In fact, metazoan morphologies are quite clumped—undispersed is the technical term—into clades with unique body plans and with significant gaps in architectural style between them, and this pattern continues among classes within phyla and to some extent even among orders within classes” (p. 340).

So, what does attenuating the rise of so many different animal bodyplans from 5–15 million years to 25–55 million years do to this pattern? Nothing. To put this in context; we supposedly diversified from our closest living relatives (chimps) 6 million years ago. The Great Apes and humans are (family Hominidae) supposedly diversified over the last c. 15 million years. Old world primates (monkeys, apes, and us) supposedly diversified over the last c. 25 million years. And the Primate order supposedly diversified over the last c. 55 million years. In other words, on the most generous timeframe we can give the evolutionists, 55 million years, the single Primate order took that amount of time to diversify to today’s state in the Cenozoic as it took for over 24 disparate phyla to arise in the Cambrian. Really?! Even if we’re generous to the evolutionists, the Cambrian explosion still looks ridiculous on their own terms.

Note also that part of the problem is that there are too few viable precursors to explain the sudden appearance of so many disparate phylum-level forms. It’s one thing to claim that there was an adaptive radiation from viable precursors (as even some creationists have argued with the Cenozoic horse fossil series1). It’s another to argue that disparate phyla could have all evolved with little evidence of fossil precursors.

Furthermore, spreading out the rise of the different animal phyla also does nothing to explain why disparity arose before diversity. All the diversity we see today has arisen within the phyla that arose in the Cambrian; no new phyla have arisen since then. Why has the disparity stayed the same over the last 500 million years, despite it arising so comparatively rapidly between 550 and 500 million years ago? Was evolution only capable of producing a slew of phyla once? Why then and there? Why not ever again? And most importantly: how can it happen, given that none of the biological mechanisms of change we observe produce anything like what we see? See More reasons to doubt Darwin.

We have several articles that explore these themes and more on the Cambrian explosion. See The Cambrian explosion, The Cambrian explosion in colorful, zoological context, and Exploding evolution.

Dealing with doubt

But let me also say something about doubt. Doubts come, and it’s impossible to stop them crossing our mind. But we are responsible for how we handle them. A few tips. First, pray, read the Bible, and fellowship with Bible-believing Christians; the staples of the Christian ‘life diet’. Don’t forsake these habits; that’s a sure-fire way to let the doubts win. Dealing with doubt.

Second, be careful about what information you take in. Study Christian apologetics material (especially at creation.com), which is aimed at building up the soul. Don’t go looking for skeptical material when you haven’t yet learned how to defend the Christian faith and control your doubts. Good material will expose you to all the skeptical arguments and objections you need to know. And study the material with other, more mature Christians, as much as possible.

Third, keep short accounts with God concerning your own personal sin. Sin not dealt with can easily lead to doubt.

Finally, be mindful of your physical and emotional state. If you’re hungry, tired, sick, or upset, don’t do apologetics/theology/philosophy. It’s taxing on the brain, and it will exhaust you, so you want to be in a good physical and emotional state when you do it.

References and notes

- Cavanaugh, D.P., Wood, T. and Wise, K.P., Fossil equidae: a monobaraminic, stratomorphic series; in: Walsh, R.E. (Ed.), Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Creationism, Creation Science Fellowship, Pittsburgh, PA, p. 143–149, 2003. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.