Can we be good without God?

What is the connection between belief in God and morality?

Trinity Baptist Church, Nairobi, Kenya.

Atheists and Christians often debate such questions. In this case, the politician’s answer is true: it really does depend upon what you mean by ‘God’ and ‘without’.

In fact, atheists not only can, but must be (at least to some extent) good without believing in God—even if they hate God with every inch of their being. If they are really made in the image of God as the Bible teaches (Genesis 1:27), then that fact must have some results. They, like all of us, are fallen (as explained in

If atheists were generally able to throw off all the shackles of morality and live their lives consistently with atheism, we’d be worried. If they could consistently live out such ideas as, ‘We’re just here to pass on our selfish genes’, ‘Survival of the fittest’ or ‘Life is ultimately all without meaning or purpose’, it would put a serious question mark over the record given to us in Genesis. It would be evidence that maybe they weren’t creatures made by God after all, and that atheism might actually be true.

The fact, though, that most atheists find themselves unable to live out such ideas is reassuring; instead, they find it necessary to live as if morality were real, hunting around for far-fetched arguments to justify this.

There are of course some atheists who have been more consistent, at least in their theoretical thinking. Believing that man is nothing more than a cosmic fluke, they realise that this means that ultimately morality is just something that was put together in the human mind, a product of evolution which has no more real authority over our behaviour than any other activity of the human mind. It’s got no more compulsion (‘you ought to do this’) than anything else thrown up by our brain cells—such as, for example, immorality! One person thinks that we should not hurt our neighbour; the cannibal, though, thinks that it’s OK to eat him. And both of those ideas are nothing more than the result of chemicals fizzing around in our heads. Neither has any real authority—they are ultimately just personal preferences.

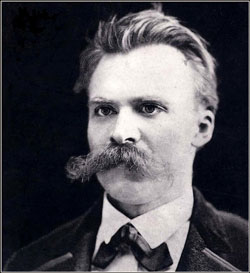

Frederich Nietzsche, the famous atheist who said, ‘God is dead’, saw that this was where the logic led. He wrote that ‘our moral judgments and evaluations are only images and fantasies based on a physiological process unknown to us.’1 The last century saw what happened when evolutionary philosophy was put into practice: Nazi genocide and euthanasia, millions butchered by Stalin, Mao and Pol Pot. Even today, ‘ethicists’ like Peter Singer support infanticide, and evolutionary envirofanatics propose population extermination. Two evolutionists wrote a book claiming that rape was a device for men to perpetuate their genes—one of the authors tied himself in knots trying to explain why rape was still wrong under his own philosophy. Fortunately, most atheists don’t carry their atheism to its logical conclusion like these horrific examples.

In any case, any atheist philosophising nicely about such systems of amorality would, in real life, be quickly brought back to his senses by a punch on the nose. He would quickly get back his old feelings about the reality of right and wrong, and start talking like a theist again, telling his assailant that what was done to him was ‘wrong’—no arguments! Don’t try telling him that his attacker’s brain is wired differently, the result of genes mutating in a different direction so that for him punching the atheist was right—he won’t accept it!

The fact is, though, that when atheists are concerned about good, or are being good, none of that is ‘being good without God’. It’s the opposite—being good with God, because God really exists and they are made in His image. To actually talk about being ‘good without God’, we would need to take a journey into a different universe: the mental universe of atheism. Because the image of God is impressed upon our nature as created beings, we’ve all assumed some ideas about right and wrong. But what kind of idea of morality is logically consistent with atheism, the idea of a universe in which we’re just highly-evolved pond goo?

British atheologian Richard Dawkins says:

‘Atheists and humanists tend to define good and bad deeds in terms of the welfare and suffering of others. Murder, torture, and cruelty are bad because they cause people to suffer.’2

Defining good and bad in terms of welfare and suffering sounds reasonable—pretty close to the Christian commandment to love our neighbour. Hurting them is bad, helping them is good. The problems do not come with the second half of Dawkins’ first sentence, but the first. ‘Atheists and humanists tend to define good and bad …’

In fact, there’s no reason to read anything that comes after that point. Whether we choose to define good and bad in terms of helping society or in terms of crushing it with an iron fist makes no difference from here. If good and bad are merely what atheists, humanists or anyone else chooses to define them as, then good and bad are merely a product of the human brain. They have no binding moral authority over us, any more than any other mere construction of the human brain has. They might make us happy, but happiness is not the same as righteousness—even a serial killer might feel that he gains ‘happiness’ from his crimes. They exist only within our cerebral chemistry, and nowhere outside of it. Like opinions on the best England football XI, or on the finest vintage of South African wine, morality is no more than one of the moveable and ever-moving feasts of human thought.

With no external or transcendent source of values, Richard Dawkins’ opinion on what is good or bad has no more authority over me or objective basis that should guide me than my preference for classical music over grunge. Both have precisely the same foundation—the ever-evolving activities of the human brain. It’s just a matter of however I happen to like or want things to be! Indeed, Dawkins has himself recognized that ultimately evolution ‘leads to a moral vacuum … in which [people’s] best impulses have no basis in nature’. He scoffs at the idea of righteous indignation and retribution against child murderers and other vile criminals, claiming that it is as irrational as Basil Fawlty3 beating his car.

To be real, though, morality must be a matter of authority: you ‘ought’ or ‘ought not’ to do this or that. Its very essence depends upon transcendence. That is, something that is ‘bigger’ than you, and tells you what to do. It cannot be something that is just a part of you or humanity in general: it must be ‘outside’ of humanity, something over and above us. Dawkins’ morality is not morality at all, but personal preference. He prefers to not cause suffering; rapists prefer to maximize their own gratification. In atheism, there’s no ultimate authority we can appeal to in order to determine whose thoughts are ‘better’. Both are just human brain activity, without any ultimate reference point by which to evaluate them.

Conclusion

Morality is real precisely because God is real. As our Creator, He is the transcendent authority—the law-giver who gets to tell us what we ‘ought’ or ‘ought not’ to do. It is because we are made by Him and are like Him that we know we cannot really treat morality as just an invention. It is because existence is more than just molecules that right and wrong are important. It is because we are made in the image of God the Creator that morality really is bigger than we are. Which means that God ultimately defines what is right and what is wrong.

At this point, the atheist is in dire straits. The first of God’s laws is to love Him with our whole being

Atheists need to face up to logic—ultimately, either nothing is immoral (because there is no God, and thus no such thing as morality) or atheism is itself immoral. There are no coherent alternatives.

References

- Nietzsche’s Moral and Political Philosophy, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 27 July 2007. Return to text.

- Dawkins, C.R., Logical Path from Religious Beliefs to Evil Deeds, 2 October 2007.

- Basil Fawlty was the character played by John Cleese in the classic 1970s British TV comedy series Fawlty Towers. He was prone to angry, irrational outbursts blaming others for his problems. In one episode he took out his frustrations on his stalled vehicle by beating it with a tree branch. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.