Noah’s Flood and the Gilgamesh Epic

Hardly anything in the Bible has been attacked as much as God’s cataclysmic judgment of Noah’s Flood. This started with a Scottish physician called James Hutton (1726–97), who decreed in 1785, before examining the evidence:

‘the past history of our globe must be explained by what can be seen to be happening now … No powers are to be employed that are not natural to the globe, no action to be admitted except those of which we know the principle’ (emphasis added).1

This was not a refutation of biblical teaching of Creation and the Flood, but a dogmatic refusal to consider them as even possible explanations—just like the scoffers Peter predicted in 2 Peter 3.

However, disbelief in the Flood has become so entrenched that even many ostensibly Christian colleges don’t teach it. Yet Jesus taught the Flood was real history, as real as His future second coming:

‘Just as it was in the days of Noah, so also will it be in the days of the Son of Man. People were eating, drinking, marrying and being given in marriage up to the day Noah entered the Ark. Then the Flood came and destroyed them all.’ (Luke 17:26–27)

In this passage, Jesus straightforwardly talks about Noah as a real person (who was His ancestor—Luke 3:36), the Ark as a real vessel, and the Flood as a real event. So those of a broadly conservative theological disposition will not deny the Flood completely, but will claim that it was merely a local event, usually in Mesopotamia (ancient Iraq).2 However, the liberals, who care nothing for Jesus’s words, go even further. A very common view is that the biblical story of Noah’s Flood was not historical at all, and was borrowed from flood legends in Mesopotamia.

The Gilgamesh Epic

In 1853, the archaeologist Austen Henry Layard and his team were excavating the palace library of the ancient Assyrian capital Nineveh. Among their finds were a series of 12 tablets of a great epic. The tablets dated from about 650 BC, but the poem was much older. The hero, Gilgamesh, according to the Sumerian King List,3 was a king of the first dynasty of Uruk who reigned for 126 years.4

However, in the legend, Gilgamesh is 2/3 divine and 1/3 mortal. He has enormous intelligence and strength, but oppresses his people. The people call upon the gods, and the sky-god Anu, the chief god of the city, makes a wild man called Enkidu with enough strength to match Gilgamesh. Eventually the two fight, but neither can win. Their enmity becomes mutual respect then devoted friendship.

The two new friends set off on adventures together, but eventually the gods kill Enkidu. Gilgamesh grievously mourns his friend, and realises that he too must eventually die. However, he learns of one who became immortal—Utnapishtim, the survivor of a global Flood. Gilgamesh travels across the sea to find Utnapishtim, who tells of his remarkable life.

The Gilgamesh Flood

In reality, it was Utnapishtim’s flood, told in the 11th tablet. The council of the gods decided to flood the whole earth to destroy mankind. But Ea, the god who made man, warned Utnapishtim, from Shuruppak, a city on the banks of the Euphrates, and told him to build an enormous boat:

‘O man of Shuruppak, son of Ubartutu:

Tear down the house and build a boat!

Abandon wealth and seek living beings!

Spurn possessions and keep alive living beings!

Make all living beings go up into the boat.

The boat which you are to build,

its dimensions must measure equal to each other:

its length must correspond to its width.’5

Utnapishtim obeyed:

‘One (whole) acre was her floor space, (660’ X 660’)

Ten dozen cubits the height of each of her walls,

Ten dozen cubits each edge of the square deck.

I laid out the shape of her sides and joined her together.

I provided her with six decks,

Dividing her (thus) into seven parts.’ …6

Utnapishtim sealed his ark with pitch,7 took all the kinds of vertebrate animals, and his family members, plus some other humans. Shamash the sun god showered down loaves of bread and rained down wheat. Then the flood came, so fierce that:

‘The gods were frightened by the flood,

and retreated, ascending to the heaven of Anu.

The gods were cowering like dogs, crouching by the outer wall.

Ishtar shrieked like a woman in childbirth,

the sweet-voiced Mistress of the Gods wailed:

“The olden days have alas turned to clay,

because I said evil things in the Assembly of the Gods!

How could I say evil things in the Assembly of the Gods,

ordering a catastrophe to destroy my people!!

No sooner have I given birth to my dear people

than they fill the sea like so many fish!”

The gods—those of the Anunnaki—were weeping with her,

the gods humbly sat weeping, sobbing with grief(?),

their lips burning, parched with thirst.’5

However, the flood was relatively short:

‘Six days and seven nights

came the wind and flood, the storm flattening the land.

When the seventh day arrived, the storm was pounding,

the flood was a war—struggling with itself like a woman

writhing (in labor).’5

Then the ark lodged on Mt Nisir (or Nimush), almost 500 km (300 miles) from Mt Ararat. Utnapishtim sent out a dove then a swallow, but neither could find land, so returned. Then he sent out a raven, which didn’t return. So he released the animals and sacrificed a sheep. This was not too soon, because the poor gods were starving:

‘The gods smelled the savor,

the gods smelled the sweet savor,

and collected like flies over a (sheep) sacrifice.’

Then Enlil saw the ark and was enraged that some humans had survived. But Ea sternly rebuked Enlil for overkill in bringing the flood. Whereupon Enlil granted immortality to Utnapishtim and his wife, and sent them to live far away, at the Mouth of the Rivers.

Here is where Gilgamesh found him, and heard the remarkable story. First Utnapishtim tested Gilgamesh’s worthiness for immortality by challenging him to stay awake for 7 nights. But Gilgamesh was too exhausted and quickly fell asleep. Utnapishtim asked his wife to bake a loaf of bread and place it by Gilgamesh every day he slept. When Gilgamesh awoke, he thought he had just been asleep for a moment. But Utnapishtim showed Gilgamesh the loaves at different stages of aging, showing that he had been asleep for days.

Gilgamesh once more lamented about his inevitable death, and Utnapishtim took pity on him. So he revealed where he could find a plant of immortality. This was a thorny plant in the domain of Apsu, the god of the subterranean sweet water. Gilgamesh opened a conduit to the Apsu, tied heavy stones to his ankle, sunk deep down, and grabbed the plant. Although the plant pricked him, he cut off the stones, and rose.

Unfortunately, on the return journey, Gilgamesh stopped at a cool spring to bathe, and a snake carried off the plant. Gilgamesh wept bitterly, because he could not return to the underground waters.

| Comparison of Genesis and Gilgamesh8 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Genesis | Gilgamesh | |

| Extent of flood | Global | Global |

| Cause | Man’s wickedness | Man’s sins |

| Intended for whom? | All mankind | One city & all mankind |

| Sender | Yahweh | Assembly of “gods” |

| Name of hero | Noah | Utnapishtim |

| Hero’s character | Righteous | Righteous |

| Means of announcement | Direct from God | In a dream |

| Ordered to build boat? | Yes | Yes |

| Did hero complain? | No | Yes |

| Height of boat | Three stories | Seven stories |

| Compartments inside? | Many | Many |

| Doors | One | One |

| Windows | At least one | At least one |

| Outside coating | Pitch | Pitch |

| Shape of boat | Oblong box | Cube |

| Human passengers | Family members only | Family and few others |

| Other passengers | All kinds of land animals (vertebrates) | All kinds of land animals |

| Means of flood | Underground water & heavy rain | Heavy rain |

| Duration of flood | Long (40 days & nights plus) | Short (6 days & nights) |

| Test to find land | Release of birds | Release of birds |

| Types of birds | Raven & three doves | Dove, swallow, raven |

| Ark landing spot | Mountains—of Ararat | Mountains—Mt Nisir |

| Sacrificed after flood? | Yes, by Noah | Yes, by Utnapishtim |

| Blessed after flood? | Yes | Yes |

Which came first?

We can see from the table that there are many similarities, which point to a common source. But there are also significant differences. Even the order of sending out birds is logical in Noah’s account. He realized that the non-return of a carrion feeder like a raven proved nothing, while Utnapishtim sent the raven out last. But Noah realized that a dove was more logical—when the dove returned with a freshly picked olive branch, Noah knew the water had abated. And its non-return a week later showed that the dove found a good place to settle.

Enemies of biblical Christianity assert that the biblical account borrowed from the Gilgamesh epic. Followers of Christ cannot agree. So in line with the Apostle Paul’s teaching in 2 Corinthians 10:5, it’s important to demolish this liberal theory.

Genesis is older

It makes more sense that Genesis was the original and the pagan myths arose as distortions of that original account. While Moses lived long after the event, he probably acted as the editor of far older sources.9 For example, Genesis 10:19 gives matter-of-fact directions, ‘as you go toward Sodom and Gomorrah and Admah and Zeboiim’. These were the cities of the plain God destroyed for their extreme wickedness 500 years before Moses. Yet Genesis gives directions at a time when they were well-known landmarks, not buried under the Dead Sea.

It is common to make legends out of historical events, but not history from legends. The liberals also commonly assert that monotheism is a late evolutionary religious development. The Bible teaches that mankind was originally monotheistic. Archaeological evidence suggests the same, indicating that only later did mankind degenerate into idolatrous pantheism.10

For instance, in Genesis, God’s judgment is just, he is patient with mankind for 120 years (Genesis 6:3), shows mercy to Noah, and is sovereign. Conversely, the gods in the Gilgamesh Epic are capricious and squabbling, cower at the Flood and are famished without humans to feed them sacrifices. That is, the human writers of the Gilgamesh Epic rewrote the true account, and made their gods in their own image.

The whole Gilgamesh-derivation theory is based on the discredited Documentary Hypothesis.9 This assumes that the Pentateuch was compiled by priests during the Babylonian Exile in the 6th century BC. But the internal evidence shows no sign of this, and every sign of being written for people who had just come out of Egypt. The Eurocentric inventors of the Documentary Hypothesis, such as Julius Wellhausen, thought that writing hadn’t been invented by Moses’ time. But many archaeological discoveries of ancient writing show that this is ludicrous.

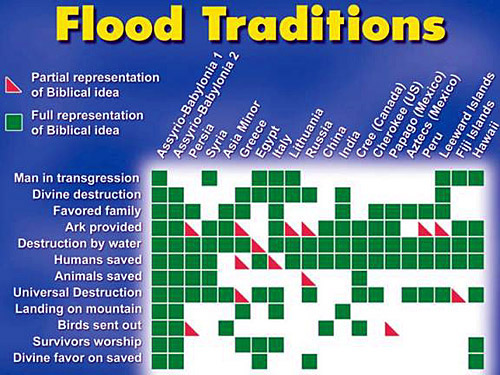

All people groups remember a global Flood

Liberals often claim that the Gilgamesh epic was embellished from a severe river flood, i.e. a local flood. This might work if there were similar flood legends only around the ancient near east. But there are thousands of such flood legends all around the world—see the chart below for some examples.11

Even the Australian Aborigines have legends of a massive flood, as do people living in the deep jungles near the Amazon River in South America. Dr Alexandra Aikhenvald, a world expert on the languages of that region, said:

‘… without their language and its structure, people are rootless. In recording it you are also getting down the stories and folklore. If those are lost a huge part of a people’s history goes. These stories often have a common root that speaks of a real event, not just a myth. For example, every Amazonian society ever studied has a legend about a great flood.’12

This makes perfect sense if there were a real global Flood as Genesis teaches, and all people groups came from survivors who kept memories of this cataclysm.

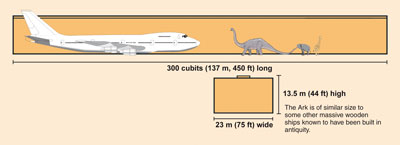

Ark shape

The Ark was built to be tremendously stable. God told Noah to make it 300×50×30 cubits (Genesis 6:15) which is about 140×23×13.5 metres or 459×75×44 feet, so its volume was 43,500 m3 (cubic metres) or 1.54 million cubic feet. This is just right to keep the boat from capsizing and to smooth the ride. There are three main types of rotation in ships (and planes), about three perpendicular axes:

Yawing, rotation about a vertical axis, i.e. the bow and stern move alternately left to right.

Pitching, rotation about a lateral axis, an imaginary line left to right, i.e. the bow and stern move alternately up and down.

Rolling (or heeling), rotating about the longitudinal axis, an imaginary line from bow to stern, tending to tip the boat on its side.

Yawing is not dangerous, in that it won’t capsize a boat, but it would make the ride uncomfortable. Pitching is also an unlikely way to capsize a boat. In any case, the enormous length of the boat would make it align parallel to the wave direction, so these disturbances would be minimal.

Click on picture for high resolution (126 kb).

Rolling is by far the greatest danger, and the Ark solves that by being much wider than it is high. It would be almost impossible to tip over—even if the Ark were somehow tipped over 60°, it could still right itself, as shown in the diagram (above).

But it would be almost impossible to tip the Ark over even a fraction of this. David Collins, who worked as a naval architect, showed that even a 210-knot wind (three times hurricane force) could not overcome the Ark’s righting moment, which would have stopped the Ark tilting much beyond 3°.13

Furthermore, Korean naval architects have confirmed that a barge with the Ark’s dimensions would have optimal stability. They concluded that if the wood were only 30 cm thick, it could have navigated sea conditions with waves higher than 30 m.14 Compare this with a tsunami (‘tidal wave’), which is typically only about 10 m high. Note also that there is even less danger from tsunamis, because they are dangerous only near the shore—out at sea, they are hardly noticeable.

Dr Werner Gitt showed that the Ark had ideal dimensions to optimize both stability and economy of material—see his DVD from the 2004 Supercamp, How Well Designed was Noah’s Ark.

Contrast that with Utnapishtim’s ark—this was a huge cube! It is harder to think of a more ridiculous design for a ship—it would roll over in all directions at even the slightest disturbance. However, the story is easy to explain if they distorted Genesis, and found that one dimension is easier to remember than three, ‘its dimensions must measure equal to each other’, and it seems a much nicer shape. The pagan human authors didn’t realize why the real Ark’s dimensions had to be what they were. But the reverse is inconceivable: that Jewish scribes, hardly known for naval architectural skills, took the mythical cubic Ark and turned it into the most stable wooden vessel possible!

Genesis is the original

The Gilgamesh Epic has close parallels with the account of Noah’s Flood. Its close similarities are due to its closeness to the real event. However, there are major differences as well. Everything in the Epic, from the gross polytheism to the absurd cubical ark, as well as the worldwide flood legends, shows that the Genesis account is the original, while the Gilgamesh Epic is a distortion.

Update: see Nozomi Osanai, A comparative study of the flood accounts in the Gilgamesh Epic and Genesis, MA Thesis, Wesley Biblical Seminary, USA, 2004, which was completed independently of this article, and provides more detail. She graciously allowed us to publish her thesis on our site—<creation.com/gilg>.

References

- Hutton, J., ‘Theory of the Earth’, a paper (with the same title of his 1795 book) communicated to the Royal Society of Edinburgh, and published in Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 1785; cited with approval in Holmes, A., Principles of Physical Geology, 2nd edition, Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd., Great Britain, pp. 43–44, 1965. Return to text.

- For refutations of the local flood compromise, see Anon., Noah’s Flood covered the whole earth, Creation 21(3):49, June–August 1999. Return to text.

- López, R.E., The antediluvian patriarchs and the Sumerian king list, Journal of Creation 12(3):347-357, 1998. Return to text.

- Heidel, A., The Gilgamesh Epic and Old Testament Parallels, University of Chicago Press, p. 3, 1949. Return to text.

- The Epic of Gilgamesh, Tablet XI,

, 12 March 2004. Return to text. - The flood narrative from the Gilgamesh Epic,

, 12 March 2004. Return to text. - At least for the real Ark of Noah, this pitch would have been made by boiling pine resin and charcoal. Indeed, the major pitchmaking industries of Europe made pitch this way for centuries. See Walker, T., The Pitch for Noah’s Ark, Creation 7(1):20, 1984. Return to text.

- Adapted from Lorey, F., The Flood of Noah and the Flood of Gilgamesh, ICR Impact 285, March 1997. Return to text.

- Grigg, R., Did Moses really write Genesis? Creation 20(4): 43–46, 1998. Return to text.

- Schmidt, W., The Origin and Growth of Religion, Cooper Square, New York, 1971. Return to text.

- From Monty White. Return to text.

- Barnett, A., For want of a word, New Scientist 181(2432):44–47, 31 January 2004. Return to text.

- Collins, D.H., Was Noah’s Ark stable? Creation Research Society quarterly 14(2):83–87, September 1977. Return to text.

- Hong, S.W. et al., Safety investigation of Noah’s Ark in a seaway, Journal of Creation 8(1):26–36, 1994. All the co-authors are on the staff of the Korea Research Institute of Ships and Ocean Engineering, in Daejeon. They also analyzed other possible threats to the Ark, such as deckwetting frequency, acceleration at various points and slamming frequency. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.