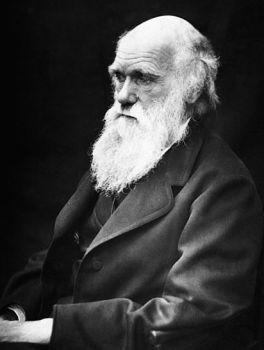

Did Charles Darwin become a Christian before he died?

A new book raises the question afresh

|

|

The publication of a new book Darwin and Lady Hope: The Untold Story1 by British research scientist Dr L. R. Croft in 2012 has reopened this topic, previously dealt with in detail by historian Prof. James Moore in his 1994 book The Darwin Legend.2 Both authors have researched the matter over 20 years, so I shall compare Croft’s claim that Darwin did return to the Christian faith, with Moore’s claim that he did not, and then give my own analysis and conclusion. (Readers who want to jump to that conclusion right up front can click here but are urged to follow the arguments and draw their own). Because this article has been of necessity substantially more lengthy (over 8,000 words all up) than most creation.com items, extensive use has been made of sidebars, so that the reader might follow the main thread more readily, returning to fill in the gaps as desired.

In what follows, readers should be aware of Moore’s bias, typified by his reference to the matter as “holy fabrication”3 and “the old evangelical slur”4—hardly the impartiality required of a historian to inspire confidence in his objectivity!

Lady Hope was an English evangelical activist, preacher, and temperance worker. So as to enable the reader to keep the flow of the main article, details of her childhood, family, marriages to Admiral Sir James Hope in 1877 and to T. Anthony Denny in 1893, her bankruptcy brought about by an ex-convict fraudster in 1911, her emigration to America in 1913, and her death in 1922, are detailed in Sidebar 1:‘Who was Lady Hope?’.

The Lady Hope story

The following account of a meeting between Darwin and Lady Hope in 1881, written by her in 1915, is what has become known as the Lady Hope story:5

Sidebar 1

Who was Lady Hope?

She was born Elizabeth Reid Cotton in Hobart Town, Tasmania, on 9 December 1842. Her father was a Captain Arthur Cotton of the British Royal Engineers. Over a period of 40 years he was responsible for constructing huge irrigation projects in India that resulted in saving millions of people from famine. For this he was knighted by Queen Victoria on 4 February 1861. In 1866, he was promoted to the rank of Major General and was made a Knight Commander of the Order of the Star of India (K.C.S.I).1 Croft tells us:

“Today General Cotton’s name is revered in India … he is the only Englishman to have had a statue erected to his memory, by the Indian people, since Independence. Furthermore, there is today a Sir Arthur Cotton Museum in the State of Andhra Pradesh, and … the Jawaharlal Nehru Technological University has recently planned the making of a documentary film about Sir Arthur Cotton’s life and work.”2

Moore’s comment on Cotton’s achievements and the many accolades he received in both the UK and India is the defamatory statement (without documentation) that he was “the man who wrung more revenue out of the Madras plantations than any previous administrator”.3

In his retirement in England, General Cotton gave lectures to the Royal Geographical Society and the British Association for the Advancement of Science. He often took along his daughter, Elizabeth, as his assistant, so she met many of the leading scientists of the day, including William Spottisworth, President of the Royal Society and Printer to H.M. Queen Victoria.4

Elizabeth’s early evangelistic and philanthropic work included the opening of a Coffee Room in Dorking, Surrey, that supplied food and non-alcoholic drinks to working men, and where she held Bible classes and prayer meetings. It was about 20 miles from Downe, home village of Charles Darwin in Kent. This was the first of several such Coffee Room ventures, which were commended by Florence Nightingale in a letter in The Times of 27 March 1878.5 Elizabeth also assisted in the evangelistic meetings of Dwight L. Moody and Ira Sankey in Scotland for six weeks in 1874 and then in London in 1875,6 counselling many women converts.7

On 6 December 1877, she married retired Admiral Sir James Hope, GCB, son of Rear-Admiral Sir George Johnstone Hope, KCB, who had commanded the 74-gun ship of the line HMS Defence at the Battle of Trafalgar. Sir James was a devout Christian and temperance advocate, and shared his wife’s passion to proclaim the gospel to drunkards and others, until his death in 1881.8 Thereafter, she engaged in visiting the elderly and sick, and doing tent evangelism in the county of Kent, including meetings near as well as in Downe.

In 1893, the widowed Elizabeth married T. Anthony Denny, a wealthy Irish businessman and temperance advocate, who was a major supporter of many evangelical enterprises, including helping William Booth purchase the Salvation Army’s headquarters and their new printing press.9 Together he and Elizabeth opened several large hostels for working men and soldiers returning from the Boer War. Denny died in 1909. Elizabeth continued to use the name ‘Lady Hope’ and began an expensive project called the Connaught Club that provided temperance and Christian accommodation for several thousand men every night. Unfortunately in this enterprise she was exploited by an ex-convict conman of many aliases but known to her as Mr Gerald Fry, to whom she entrusted her finances, only to find out too late that he had swindled her. In 1911, she was declared bankrupt.10

Croft tells us that Fry “had been in prison many times … he had been accused of the attempted murder of his wife and children, In addition he had been responsible, through his dishonesty, for the bankruptcy of several other people. Moore deplorably describes this seasoned criminal and despicable fraudster as “a gentleman”,11 presumably so his readers will conclude that Lady Hope was solely responsible for her own bankruptcy.

In 1913, Lady Hope left England and settled in America. In 1922, returning to England by the Pacific shipping route, she got as far as Sydney, Australia, where she died of cancer. Her tomb may be seen in Rookwood Cemetery there to this day.

References

- Croft, pp. 51–53. Return to text.

- Croft, pp. 18-19. Return to text.

- Moore, p. 84. Return to text.

- Croft, pp. 79 and 127. Return to text.

- Croft, p. 56. Return to text.

- Moore contemptuously says that the American evangelists Moody and Sankey were “a gifted duo, like their English contemporaries Gilbert and Sullivan”, Moore, p. 83. Gilbert and Sullivan were composers of comic opera in the Victorian era. Return to text.

- Croft, ref, 1, p. 63. Return to text.

- Moore insultingly attributes Elizabeth’s marriage to the Admiral as due to her vanity, Moore, p. 85. Return to text.

- Croft, p. 69. Return to text.

- Croft, pp. 69–71. Return to text.

- Moore, p. 90. Return to text.

It was one of those glorious autumn afternoons that we sometimes enjoy in England when I was asked to go in and sit with the well-known professor Charles Darwin. He was almost bedridden for some months before he died. I used to feel when I saw him that his fine presence would make a grand picture for our Royal Academy: but never did I think so more strongly that on this particular occasion.

He was sitting up in bed, wearing a soft embroidered dressing gown of rather a rich purple shade. Propped up by pillows he was gazing out on a far-stretching scene of woods and cornfields, which glowed in the light of one of those marvellous sunsets which are the beauty of Kent and Surrey. His noble forehead and fine features seemed to be lit up with pleasure as I entered the room.

He waved his hand toward the window as he pointed out the scene beyond while in the other hand he held an open Bible which he was always studying.

“What are you reading now,” I asked as I seated myself by his bedside.

“Hebrews!” he answered — “still Hebrews, ‘The Royal Book’ I call it. Isn’t it grand?”

Then placing his finger on certain passages he commented on them.

I made some allusion to the strong opinions expressed by many persons on the history of the Creation, its grandeur and then their treatment of the earlier chapters of the Book of Genesis.

He seemed greatly distressed, his fingers twitched nervously, and a look of agony came over his face as he said:

“I was a young man with unformed ideas. I threw out queries, suggestions wondering all the time over everything; and to my astonishment the ideas took like wildfire. People made a religion of them.”

Then he paused and after a few more sentences on “the holiness of God” and “the grandeur of this Book” looking at the Bible which he was holding tenderly all the time, he suddenly said:

“I have a summer-house in the garden, which holds about thirty people. It is over there,” pointing through the open window. “I want you very much to speak there. I know you read the Bible in the villages. Tomorrow afternoon I should like the servants on the place, some tenants, and a few of the neighbours to gather there. Will you speak to them?”

“What shall I speak about?” I asked.

“Christ Jesus” he replied in a clear emphatic voice, adding in a lower tone, “and his salvation. Is not that the best theme? And then I want you to sing some hymns with them. You lead on your small instrument do you not?”

The wonderful look of brightness and animation on his face as he said this I shall never forget, for he added:

“If you take the meeting at three o’clock this window will be open and you will know that I am joining in with the singing.”

How I wished that I could have made a picture of the fine old man and his beautiful surroundings on that memorable day!

The above narrative first appeared in print in the American Baptist magazine, the Watchman-Examiner, and a few days later in the religious section of the Boston Evening Transcript of 21 August 1915. Croft tells us that a footnote in this newspaper said that Lady Hope had related it at a prayer meeting at a Christian conference held a few days earlier at Northfield College, Massachusetts, and then Prof. A.T. Robertson, an eminent New Testament scholar, had repeated it from the platform.6 It was then written down by Lady Hope at the request of the editor of the Watchman-Examiner. Moore adds that Robertson was filling in when none of the English guest speakers had shown up, being detained by illness or the 1914–18 War in Europe, and that he was expounding the Epistle to the Hebrews from the original Greek at the morning Bible classes there.7

Since then the story has been repeated many hundreds of times in Christian tracts, books, magazines, articles, etc. to the present day, usually with the added claim that it demonstrated Christian faith on Darwin’s part.

Was there more than one meeting?

Two or three words in the above account seem to indicate that Lady Hope may have visited Darwin more than once. Despite the family’s denials, this is not unfeasible. Both Charles and Emma shared Lady Hope’s concern for drunkenness, and would undoubtedly have known of the temperance meetings she had held in the villages near as well as in Downe in 1880–81.8 Charles would also have known of and been very interested in her father’s ‘deep cultivation’ system of obtaining high yields of crops, from the many reports about this in the press.9 She had met leading scientists of the day (see Sidebar 1) including Darwin’s colleague, William Spottiswoode, President of the Royal Society, who Croft says “just a few months earlier, had entertained Lady Hope on the verandah of his country house”,10 which was in Kent. And Moore says that Darwin kept in touch with some of his former Beagle shipmates, particularly Bartholomew Sulivan,11 who himself achieved the rank of Admiral and whose son had served under her husband, Admiral Sir James Hope.12 So Darwin and Lady Hope had plenty of mutual interests, which could have warranted there being more than one meeting.

Moore concedes that Lady Hope was indeed invited to Down House to meet Darwin, and he says that her account of the meeting “contains startling elements of authenticity”.13 These include her description of the view from the Down house window, the sunset, the colour of Darwin’s dressing gown, his finger-twitching, and her mention of a summer-house in the garden, which indeed existed at the end of the sand-walk (although it may not have been big enough to hold 30 people as Lady Hope remembered Darwin saying). From the weather details given by Lady Hope, compared with the National Meteorological records, and noting dates when Francis Darwin was absent, Moore concludes that the meeting probably took place between 28 September and 2 October 1881.14 From similar considerations Croft opts for 8 November 1881.15

Reactions to the story

Darwin’s family members were greatly shocked by the newspaper report of her story when it reached England. They mounted counter attacks involving denying that any such event had taken place and charging her with fabrication, even though as Moore says:

“none of the deniers but Bernard was living full-time at home when the alleged interview(s) with Darwin took place. And Bernard was then a child. Nor in 1915 or 1916, when Lady Hope’s story first came to the family’s attention was any adult alive who had been regularly present in Down House during 1881–82 … ”.16

First to enter the fray was Charles’ son, Francis, who in 1887 had published an edited version of his father’s Autobiography, a work which Darwin had written principally for his family’s interest. At the insistence of Darwin’s widow, Emma, and with the family’s eventual consensus, Francis had expunged from this work Charles’ most vehement anti-Christian beliefs, along with some internal family relationships, amounting to nearly 6,000 words. This concealed the depths of Charles’ unbelief, and allowed the family to present to the world their own sanitized image of Charles as the good and noble unbeliever, the gentlemanly agnostic.17 Croft quotes a letter of 8 November 1915 from Francis Darwin to Prof. A.T. Robertson that said:

Down House.

“Neither I nor other members of my family have any knowledge of Lady Hope and there are almost ludicrous points in her statement that make it impossible to believe that she ever visited my father at Down … .”18

Moore quotes two Francis letters. In the one dated 27 November 1917 Francis wrote:

“Lady Hope’s account of her interview with my father is a fabrication, as I have already publicly pointed out. I have no reason whatever to believe that he ever altered his agnostic point of view, as given in my ‘Life of Charles Darwin’ (in vol. 1, p. 55).”19

In a similar letter dated 28 May 1918, Francis wrote: “I have publicly accused her of falsehood, but have not received any reply.” Concerning this Moore says, “The second letter mentions a ‘public’ accusation, possibly in 1916, which has not been located.”

Darwin’s married daughter, Henrietta Litchfield, had a letter published in The Christian journal in 1922, from which Moore quotes her as saying (inter alia): “Lady Hope was not present during his last illness or any illness. I believe he never even saw her. … He never recanted any of his scientific views, either then or earlier. We think the story of his conversion was fabricated in [the] USA. … ”20

Later, Darwin’s granddaughter, Nora Barlow, had her say. Moore describes it this way:

“In 1958, having just published the unexpurgated Autobiography of Charles Darwin, with the ‘damnable’ bits restored,21 she spied the old evangelical slur in the correspondence columns of The Scotsman.”

Moore reproduces Nora’s reply, published on p. 6 of The Scotsman on 8 May 1958. In it she mostly quoted or paraphrased a letter of Henrietta’s.22

Sidebar 2

The very dubious Fegan letters

According to Moore, Fegan dictated both these letters to his 22-year-old private secretary, A.W. Tiffin, who then typed them but (for some unstated reason) kept carbon copies (apparently instead of giving them to the rightful owner, Fegan). Then, 52 years later, in 1977, when Tiffin was 74 and living in North Adelaide, Australia, Moore says:

“[Tiffin] quoted the less personal portions in a typescript letter to Rev. A. Sowerbutts, editor of The Flame, in which a version of Lady Hope’s story had just appeared. A year later a copy of this letter, a typescript copy of the missing passages, and a copy of Pratt’s tract [one written by Pratt entitled ‘What is Truth? Was Charles Darwin a Christian?’] were supplied by Tiffin to my colleague Colin Russell of the Open University. … Thanks to Prof. Russell, Fegan’s replies have been reconstructed and are published here for the first time.”1

This all seems very implausible. If the letters were indeed written by Fegan, and if Tiffin did indeed still have carbon copies half a century later, and if Tiffin in South Australia had any reason to contact Prof. Russell at the Open University in the UK, surely the easiest way for Tiffin to have told Russell what the letters said would have been for Tiffin to have sent photocopies of them. This would have avoided both the need and the opportunity for them to be ‘reconstructed’. Why did this not occur? Did Tiffin retype them from memory? If so, it would cast a huge blanket of doubt over the veracity of everything that Fegan allegedly wrote. Moore is the last recipient in a four-person grapevine. So Moore’s evidence of Russell’s reconstruction of Tiffin’s typescripts of his purloined carbon copies of any letters that Fegan allegedly wrote is hearsay, and not just second-hand hearsay but fourth-hand! Hearsay evidence is inadmissible in a court of law because it is uncheckable and so untrustworthy as to its accuracy and credibility; also it could be the source of unchallengeable slander (as here!). The rationale for the rule against hearsay especially in the context of criminal allegations is summarily that only the best and most direct evidence sworn or affirmed to be true should be adduced and relied on to prove any fact against a person. Moore concedes: “Fegan’s reliability as a witness, no less than Lady Hope’s is open to question.”2 But Moore went ahead and published his two Fegan letters anyway,3 presumably because they contain the only assassination of Lady Hope’s personal character that he can proffer to his readers.

In summary, the letters claim:

1. Fabrication by Lady Hope

One letter says:

“[T]he interview as described by Lady Hope … never took place. … And when Sir Francis Darwin says that Lady Hope’s story is a fabrication, that denial is quite enough for anybody who knows the high standards of truth which the Darwins inherited from their father.”

However, this contradicts Moore’s conclusion that the meeting did occur. Also for Fegan to have accepted the word of the rationalist and freethinker Francis Darwin in preference to that of the highly respected evangelist Lady Hope (let alone attribute high standards of truth to the whole Darwin family), would have been extreme naivety on Fegan’s part. Furthermore Francis was not present so could not say anything from first-hand knowledge. Croft says that Fegan was a devout Christian of the strict Plymouth Brethren, and says: “I find it hard to believe that such a person would make a character assassination of a fellow Christian.”4

2. Subterfuge by Lady Hope

One letter says:

“Lady Hope broke T.A. Denny’s heart. The climax of her extravagance came when he discovered that, unknown to him, she was running a River Club. He went down to see it, and was seized with illness, which necessitated his lying on a water bed until he passed away.”

However, Lady Hope and husband T.A. Denny worked together on their many evangelistic and humanitarian projects, which he, a millionaire,5 was only too happy to finance. In fact, Moore says: “Having made his fortune in pork, he larded the coffers of many evangelical enterprises … .”6 Concerning the absurdity attributed to Fegan that Denny died on a water bed as a result of seeing a River Club that his wife was running without his knowledge, Moore says this “river club” was “to cater for down-and-outs along the Thames”,7 i.e. something that Denny surely would have approved of and happily financed when he found out about it. Furthermore Croft’s research has elicited that: “Mr. Denny died on Christmas Day 1909, when he was ninety-one years old. His death certificate states that the cause of death was ‘cardiac syncope seven hours’ and that he died at Buccleach House, Richmond”,8 i.e. not on a water bed at any River Club.

3. Unwillingness by Fegan to give a reference

Fegan says he refused to give Lady Hope a letter of commendation she requested when she left for America, and he says: “I had considerable uneasiness about her sayings and doings, both in her husband’s lifetime and afterwards … ”

This alleged request for a commendatory letter by Lady Hope is very curious. She had far more social standing in her own right and among the rich and famous in Britain than Fegan ever did. She was the daughter of a British General, and the widow of the British Admiral of the Fleet who had been the principal aide-de-camp to Queen Victoria.9 She had actively participated in the Moody-Sankey revival crusades of 1874–75, and had founded the Coffee Room movement that had been praised by Florence Nightingale in a letter in The Times on 27 March 1878.10 The Preface to her book More About our Coffee Room had been written by Lord Shaftesbury, leader of the evangelical movement in England.11 She was the close friend of evangelical Christian Sir Robert Anderson, who had been head of Scotland Yard’s Criminal Investigation Department at the time of the ‘Jack the Ripper’ murder investigations.12 She was also the author of numerous religious books which, according to Croft, were being published in America at the time of her emigration there.

Furthermore the alleged request for a reference was a couple of years before the publication of the Lady Hope story in 1915, and whatever Lady Hope may have said or done while married to either of her two husbands was none of Fegan’s business. Croft notes some other “curious anomalies” in these letters, e.g. one letter describes the Unitarian Emma Darwin as “a devout Christian” and the other calls her “a sincere Christian”. This is not something that Fegan, a Plymouth Brethren Christian, would be likely to say because Unitarians do not accept the divinity of Christ. And in a postscript to one letter Fegan asks why Lady Hope never cleared her name from the slur of dishonesty made by Francis Darwin. In reply, Croft suggests that any such recommendation of self-justification in a secular court would be surprising if written by a member of the Plymouth Brethren, because, “Is it not what a Christian expects, namely to have all manner of evil said against them.”13

So are these two transcribed and reconstructed letters the work of J.W.C. Fegan or have they been ‘embroidered’ (by person or persons unknown), not to say ‘fabricated’, the term Moore repeats the most regarding the writings of Lady Hope? Reliable evidence they are not! Moore does not enhance his case against Lady Hope or indeed his own reputation by advancing such questionable material as evidence to his readers.

References

- Moore, pp. 153–54. Readers should note that this means there is no way to confirm or refute anything they say by inspecting either the original letters or the original carbon copies, or even confirm that the alleged original letters ever actually existed. Return to text.

- Moore, p. 154. Return to text.

- Moore, pp. 154–63. Return to text.

- Croft, p. 80. Return to text.

- Moore, J., Telling Tales: Evangelicals and the Darwin Legend, Chapter 9 of Evangelicals and Science in Historical Perspective, p. 224, Oxford University Press, New York, 1999. Return to text.

- Moore, p. 84. Return to text.

- Moore, p. 90. Return to text.

- Croft, p. 84. Return to text.

- Croft, p. 65. Return to text.

- Croft, p. 56. Return to text.

- Croft, pp. 64, 86; also mentioned by Moore, pp. 97, 181. Return to text.

- Croft, p. 101; also mentioned by Moore, p. 118. Return to text.

- Croft, p. 87. Return to text.

The Fegan letters

The foremost modern-day criticism of the Lady Hope story is that by Prof. Moore in The Darwin Legend. Seeing he concedes the meeting did take place, all claims that it did not are not worth refuting. However, character assassination of Lady Hope is another matter. In Appendix D of The Darwin Legend, titled “Mr. Fegan Protests, 1925”, Moore gives his readers two letters allegedly written by English temperance worker J.W.C. Fegan in May 1925 in reply to two enquirers about the Lady Hope story. One letter is said to be to a Mr J.A. Kensit of the Protestant Truth Society, and another one, almost identically critical, to a Mr S.J. Pratt of London. As these are the source of the worst and only character assassination of Lady Hope (apart from the charges of fabrication, i.e. lying), I have examined them in some detail in Sidebar 2: ‘The very dubious Fegan letters’, which gives many reasons why, in accord with the sidebar’s title, they may not be relied upon.

Some relevant matters

So much for the details of the Lady Hope story. The following relevant matters now need to be considered, assuming Lady Hope’s record of her conversation with Darwin is a true account of what happened, but bearing in mind that there was no third-party witness to this. Nor did either Charles Darwin or Lady Hope make any (known) diary or other record of the event.

1. Lady Hope never claimed any conversion took place at the meeting.

According to what Lady Hope wrote, no evangelism took place at the meeting. E.g. when Charles mentioned Jesus Christ, Lady Hope did not ask him if he had accepted Christ as his own Saviour. And when Charles suggested she preach on salvation to the servants, she did not ask him if he had accepted this salvation for himself. So any claim that Charles embraced (or re-embraced) Christianity at this meeting is without foundation.

2. There is no written record by Darwin of any change of heart

Some Christians have claimed that Lady Hope’s account shows that Charles had already returned to the Christian faith prior to the meeting, albeit in his advanced years.23 In support of this as a possibility, Croft cites Prof. Antony Flew (1923–2010) and Prof. C.E.M. Joad (1891–1953), two of the most renowned British atheists of their eras, who both recanted very late in life and “decided there is a God after all”. In 2004, Flew, in public repentance, confessed: “As people have been influenced by me, I want to try and correct the enormous damage I have done.” He did this with his last book There is a God: How the World’s Most Notorious Atheist Changed his Mind, published in 2007.24 Likewise Joad, who for years preached his atheistic doctrines weekly, courtesy of the BBC, in 1952 (the year before he died) “he recanted and published an account of his journey back to faith” for all his former listeners to read, “in his book, The Recovery of Belief.”25

There is no known such ultimate book by Darwin in penitence and regret, although to write such a treatise would have taken time—possibly more time than there was before his death. What then of a short essay or any document by Charles in the several months before he died that repudiates any portion of his evolutionary belief system? We have no record of any attempt by him to correct the atheistic worldview that his theory was so effectively propagating. Some have suggested that the family had a vested interest in seeing that any such recantation never saw the light of day. However, for any such censorship to apply to any eleventh-hour article by Darwin involves two speculations:

- that Charles did in fact write such a recantation; and

- that it was then suppressed by the family.

Note that the family appears to have been unaware of the meeting until 1915 or 1916, some 34 years after the event.

Also, there is no record of any relevant letter to his closest friend and confidant of his innermost thoughts (see ref. 26), J.D. Hooker (1817–1911), to whom he once wrote: “you are the one living soul from whom I have constantly received sympathy”.26

3. Darwin met with atheists Aveling and Büchner on 28 September 1881.

Lady Hope was not the only person whom Darwin invited to Down House in the autumn of 1881. Two atheists, Edward B. Aveling and Ludwig Büchner (who was President of the Congress of the International Federation of Freethinkers held in London on 25, 26, and 27 September 1881) contacted Darwin after the Congress had concluded and they were invited by Darwin to lunch with him the following day, i.e. 28 September 1881. The discussion, after lunch, involved Charles, Aveling, Büchner and Francis Darwin. A report of this was published in 1883 by Aveling in a pamphlet entitled The Religious Views of Charles Darwin that sold for one penny.27 Aveling wrote:

[W]e fell to talking, on his own suggestion, about religion. … the first thing he said was, “Why do you call yourselves Atheists?”

Very respectfully the explanation was given, that we were Atheists because there was no evidence of deity … that whilst we did not commit the folly of god-denial, we avoided with equal care the folly of god-assertion: that as god was not proven, we were without god (άϑεοι) and by consequence were with hope in this world, and in this world alone. As we spoke, it was evident from the change of light in the eyes that always met ours so frankly, that a new conception was arising in his mind. He had imagined until then that we were deniers of god, and he found the order of thought that was ours differing in no essential from his own. For with point after point of our argument he agreed; statement on statement that was made he endorsed, saying finally: “I am with you in thought, but I should prefer the word Agnostic to the word Atheist.”28

Upon this the suggestion was made that, after all, “Agnostic” was but “Atheist” writ respectable, and “Atheist” was only “Agnostic” writ aggressive. … At this he smiled and asked: “Why should you be so aggressive? Is anything gained by trying to force these new ideas upon the mass of mankind? It is all very well for educated, cultured, thoughtful people; but are the masses yet ripe for it?” …

Then the talk fell upon Christianity, and these remarkable words were uttered: “I never gave up Christianity until I was forty years of age.”

I confess that a great joy took possession of me as I heard a statement by its implication so encouraging. … The step taken by so many of us had been taken by him long ago. … He was asked, with all deference, the reason of the long delay. With a charming frankness, he made answer that he had not had time to think about it. His time had been so occupied by his scientific work, that he had none to spare for the careful study of theological questions. …

[But] he had given attention to the matter. For, on further inquiry, he told us that he had, when of mature years, investigated the claims of Christianity. Asked why he had abandoned it, the reply, simple and all-sufficient, was: “It is not supported by evidence.”

This meeting and the conversation that took place were confirmed by Francis Darwin in his 1887 Life and Letters of Charles Darwin, in which he wrote: “Dr. Aveling gives quite fairly his impressions of my father’s views”; and concerning the terms ‘atheist’ and ‘agnostic’ Francis made it quite plain that “My father’s replies implied his preference for the unaggressive attitude of an Agnostic.”29

The above agnostic sentiments expressed by Darwin were uttered a day or two before his meeting with Lady Hope (if Moore’s date of ‘between 28 September and 2 October 1881’ for this is correct), or 6 weeks before (if Croft’s date of 8 November 1881 is correct).

4. Lady Hope’s final account

Croft concludes his book with some quotations from what Lady Hope wrote, not from her first 1915 magazine/newspaper story, but from a final account contained in a letter she wrote to a Prof. James Bole in the early 1920s (which he did not publish until 1940).30 In this last letter, Lady Hope had Darwin calling the book of Hebrews “the Royal Epistle”, and saying: “this book, I never tire of it.”31 She also wrote: “And he began to comment on some of the great Gospel truths, which I only regret extremely I cannot give verbatim.” And then: “He spoke of Christ in this way: ‘He is the King, the Saviour, the Intercessor, dying, living,’ and discoursed rather freely, and with great animation on the different parts of the subject.” And finally Darwin’s reply to her question “What shall I speak on?” Lady Hope gives as “‘Oh, on the Lord Jesus Christ’, he answered most earnestly.”32

Concerning the above additions to the original Lady Hope story, it should be noted:

- The 1915 account which omits these additional words by Darwin was written when the event was fresher in Lady Hope’s mind than it was in the early 1920s, when she explicitly says she cannot remember his exact words. They appear to be somewhat retroactively coloured, but also are obviously a clear indication of her impressions.

- Concerning the word ‘Lord’ now attributed to Darwin, I am aware of 1 Corinthians 12:3b which attests that “no one can say that Jesus is Lord except by the Holy Spirit”. But also Jesus said: “Why do you call me ‘Lord, Lord,’ and not do what I tell you?” (Luke 6:46). And: “Produce fruit in keeping with repentance” (Matthew 3:8). Acts 26:20 says that when people turn to God they should “demonstrate their repentance by their deeds” (NIV).

5. Darwin promoted his theories and particularly his Descent of Man in the month he died

Just a few days before he died on 19 April 1882 Darwin wrote a short Preliminary Notice or introduction to an article by W. Van Dyck on sexual selection in Syrian street dogs. Darwin’s contribution was received by the Zoological Society of London on 4 April 1882, and the day before that Darwin wrote to P.L. Sclater enclosing a copy of Van Dyck’s paper, very anxious that it should be published. In this Preliminary Notice, Darwin referred his readers favourably to two of his books. One was his Variation Under Domestication, in which he promotes his theory of evolution by natural selection, introduces pangenesis, and opposes any divine intervention or guidance in nature. The other was The Descent of Man, of which the first chapter is entitled “The Evidence of the Descent of Man from Some Lower Form.”

6. The personalities of Darwin and Lady Hope

-

Charles Darwin

Charles was a frequent equivocator and vacillator. As a student he was captivated by Paley’s watch argument for design, but then abandoned this in favour of Lyell’s long-age uniformitarianism in the latter’s Principles of Geology that ridiculed recent creation in favour of an old earth. Then in the 1859 1st edition of his Origin of Species Darwin did not mention the Creator in the famous last sentence of this work, but added the words ‘by the Creator” in the 1860 2nd edition and the 1861 3rd edition, only to write in an 1863 letter to his closest friend, J.D. Hooker: “I have long regretted that I truckled to public opinion & used the Pentateuchal term of creation, by which I really meant ‘appeared’ by some wholly unknown process.”33 Despite this ‘long regret’, expressed by Darwin in 1863, he kept the ‘Pentateuchal term’ in the 1866 4th edition, and the 1869 5th edition, and the 1872 and 1876 6th editions of his Origin.34 Did he not have the courage to change it back?

Also Darwin shunned all personal confrontations and public debates, being only too happy to leave these consequences of his theory to the aggressive Thomas Huxley, also known as ‘Darwin’s bulldog’.

-

Lady Hope

Very little reliable information is known about the personality of Lady Hope, except for what Croft has written, based on his extensive research. What emerges is that she appears to have been a lady of energy and integrity. In addition, she seems to have been somewhat over-trusting, possibly even naïve, in the matter of her finances, which she entrusted to an ex-convict conman named Gerald Fry, whom she befriended but who then swindled her (see Sidebar 1).

Did Lady Hope fabricate her story, as claimed by Darwin’s family and Moore with his alleged ‘Fegan letters’?

Problems (for Moore):

- The checkable parts of her story are all true, as conceded by Moore.

- As a God-fearing, evangelical Christian, Lady Hope had no reason to lie and every reason not to, something which could not be said of an agnostic, whether gentleman or other.

- In Chapter 10 Truth or Fable of his book, Croft has checked two of Lady Hope’s other stories (which Moore says were not historic) and found them accurate in every detail, such as the identity of the people described, where they lived, the cause and date of their death, etc. Croft writes: “The overall conclusion is clear. Not only are Lady Hope’s stories perfectly truthful, as one would expect of a evangelical Christian, but they are extremely accurate … .”35

- All the accusations of fabrication against Lady Hope have been brought by people who were not present at the meeting, and/or have shown themselves to be hostile to the Christian Gospel.

- Although Lady Hope related her story to a few friends in the 1880s, she appears to have considered it of little importance or she forgot about it for three decades—until Robertson’s Bible studies on Hebrews in 1915 apparently brought it back into her memory. I.e. she did not spend her life promoting it.

So bearing in mind all the above factors, and accepting that Lady Hope’s story was not a fabrication, what are the possible options concerning whether Darwin converted?

The Options

1. Darwin converted at some time prior to his meeting with Lady Hope, as she appears to have concluded.

Problems:

- At the Lady Hope meeting Darwin did not personally profess saving faith or give any testimony as to when he might have acquired this. He spoke to Lady Hope commending certain Christian doctrines and the Bible, but not to the extent of “I believe … (these same doctrines).”

- Darwin professed agnosticism and gave his ‘non-Christian-at-age-40’ testimony to Aveling and Büchner a few days before he met Lady Hope.

- He promoted his evolutionary ideas and especially his Descent of Man in the (Preliminary Notice) article published in April 1882, a few months after he met Lady Hope.

- There is no corroboration from Darwin about any conversion, either written or spoken, either public to the world or private to his friends, that confirms what Lady Hope claimed or interpreted from what he said to her.

- There is no evidence of any conspiracy on the part of his family to suppress any such word on Darwin’s part. Of course ‘absence of evidence is not evidence of absence’.36

2. Darwin did not convert, either before or at the meeting.

Problems:

- Darwin’s conversation with Lady Hope would then appear to have been a sham; however his tendency to equivocate (as discussed above) is a possible explanation for this. When one is talking to leaders of atheism it is appropriate to discuss atheism, and when to a Christian leader to discuss aspects of Christianity.

- Lady Hope would then have to have been rather naïve to have formed the conclusions she did from what Darwin said to her, even though she was an experienced evangelist and personal worker.

- So why did Darwin bother to invite her to meet him? Possibly because he was known for his interest in the good social outcomes of Christian work, having become aware of the results of missionary work among the Fuegians. See my article Darwin’s savages.

So, did he convert?

Each reader is free to form their own conclusion from the evidence. As shown, neither of the two possible options is without its problems. My conclusion, for what it is worth, is that he did not. (Note that I am assuming that the original 1915 Lady Hope story is a correct report, and am granting Croft’s meticulous exoneration of Lady Hope’s character and veracity.)

In my view, the assumption that Darwin did not convert is relatively easy to reconcile with the available evidence. (For those who wonder how Darwin’s reported comments to Lady Hope, if one grants their verbatim accuracy, could fit with this conclusion, I offer some comments in Sidebar 3: ‘If not a Christian … ?’ However, my conclusion of non-conversion does not depend on these.)

In contrast, the notion that he did become a Christian seems to me to be very difficult to reconcile with several aspects. Foremost among these, in my judgment, is his written promotion of both his theory and his powerfully anti-biblical book on human evolution, just days before his death and after the Lady Hope meeting. (As for the suggestion that this might be because he became a ‘theistic evolutionist Christian’, my reasons for not taking this seriously are given in Sidebar 4: ‘Darwin and theistic evolution’.)

Even those, whether a part of CMI or not, who disagree with me on this will presumably agree that uncertain claims are not worth relying on. And that therefore it continues to be appropriate for CMI to include Darwin’s alleged recantation as one of the items in our list of arguments that we suggest creationists should not use. In any case, the truth or otherwise of creation or evolution is not affected by whether or not Darwin changed his mind.

Sidebar 3

If not a Christian, how to understand Darwin’s words to Lady Hope?

I here discuss the issues that arise when trying to reconcile Darwin’s reported actions and words at the Lady Hope meeting with my own conclusion that the evidence points away from a true conversion.

According to Lady Hope’s 1915 account, which I will assume to be true, Darwin was reading Hebrews when she arrived and he commented on certain passages. She did not tell us what these Hebrews verses were or what Darwin said about them, or could not remember. Instead she alluded to the strong opinions of many creationists of her day regarding the grandeur of Creation and their treatment of the earlier chapters of Genesis.

Darwin reportedly replied with some self-deprecating remarks, which may have been by way of self-vindication, but which also had the effect of changing the subject—intended or otherwise.

“I was a young man with unformed ideas. I threw out queries, suggestions wondering all the time over everything; and to my astonishment the ideas took like wildfire. People made a religion of them.”

His ideas no doubt were queries, suggestions, and things that he wondered about when he was a young man, but then came the time when he published them in his Origin of Species in 1859 when he was aged 50, with the sixth edition published in 1872 when he was 63. His application of his theory to humans become generally public only after he published The Descent of Man in 1871, with the 2nd Revised and Augmented Edition in 1874, when he was 65.

In the General Summary and Conclusions chapter of The Descent he wrote:

“I am aware that the conclusions arrived at in this work will be denounced by some as highly irreligious; but he who denounces them is bound to shew why it is more irreligious to explain the origin of man as a distinct species by descent from some lower form, through the laws of variation and natural selection, than to explain the birth of the individual through the laws of ordinary reproduction.”1

And in his Autobiography, written in 1876 when he was 67, Darwin said:

“I can indeed hardly see how anyone ought to wish Christianity to be true; for if so the plain language of the text seems to show that the men who do not believe, and this would include my Father, Brother and almost all my best friends, will be everlastingly punished. And this is a damnable doctrine.”2

So in 1881 when Darwin met Lady Hope, these were no longer unformed ideas, no longer those of a young man, and no longer queries or suggestions, but were the summary and conclusions of his life obsession! Did he have doubts? Yes, most of his life, it seems, which could partly explain his delay in wanting to publish the Origin, and which could have been one of the causes of his many-years-long illness (see Darwin’s mystery illness), perhaps also of his nervous finger-twitching.

Darwin asked Lady Hope to speak to the servants, tenants and neighbours, on the following day, on the subject of Christ Jesus and his salvation, and said he intended to join in the singing.

In her letter written to Prof. Bole in the early 1920s, Lady Hope says concerning this proposed 30-person meeting: “But it never took place, I feel sure there was a lack of sympathy on these lines in the house.”3

Was Darwin’s mention of the meeting another attempt to change the subject, thus diverting the good lady’s interest and attention to the prospect of preaching the Gospel to 30 people the next day? If so, this would have been successful, as it would have effectively ended the religious part of their conversation. That fits with Darwin’s well-known aversion to all personal confrontation, though the problem with this is that it would have been disingenuous to the extreme, something that does not sit well with his transparency in other writings. And why would he have been reading Hebrews if his comments were a total sham? There were other ways to impress without going to those lengths.

It is quite conceivable that he had indeed warmed considerably towards Christianity in the later part of his life. After all, he had supported the South American Missionary Society for decades, impressed by its work among the Fuegians he had formerly disparaged as primitive barbarians. And he did appreciate the sobering and reforming effect of the Gospel on those who had been drunkards, layabouts, etc. As such, then, he may well have been going through a period of reflection and was appreciating reading Scripture from Hebrews. If Croft’s date for the Lady Hope meeting is right, then he had had some six weeks to shift his position after the Aveling meeting—something that also fits with his tendency to vacillate. If in fact his comments about the meeting were not merely an attempt to politely avoid being confronted by the claims of Christ by his visitor, then the fact that the Gospel meeting never took place may have been, as Lady Hope suspected, the result of family resistance. But it may also have been one more example of that vacillation tendency.

Nonetheless, though it may have been sincere as far as it goes, an appreciation of the Bible does not equate to saving faith. It can be quite superficial, on an aesthetic level, even providing a (false) comfort for unbelievers. More than one unsaved person has been comforted, sometimes even regularly, by such wonderful words as in Psalm 23, for example.

He may even have quickly lapsed from this back to his former state, having ‘come to his senses’ and realised at some level that the cost of following Christ was something he was simply not prepared to accept—i.e. facing the music with his family members, and having to recant publicly (Sidebar 4) to what would have been the astonishment/shock of all his friends and correspondents.

In this life we shall never know. Nevertheless, from the evidence already presented, it does not seem likely that we shall meet up with Darwin in heaven.

References

- Darwin, C., The Descent of Man, 2nd Edition, p. 613, John Murray, London, 1874. Return to text.

- Barlow, N., Autobiography of Charles Darwin: With original omissions restored, Collins, London, 1958, p. 87. Return to text.

- Moore, pp. 130–134. Return to text.

Sidebar 4

Darwin and theistic evolution

The fact that Darwin still promoted selection theory, as well as his book on human evolution (Descent of Man), well after the date that some think he may have become a Christian readily gives rise to the thought that perhaps he became a ‘theistic evolutionist’. To me that seems highly unlikely. Darwin, of all people, knew of the implications of his theory. He had defended it strongly not just against the idea of creation, but against those who tried to combine the two ideas, which included A.R. Wallace.1 He also showed in his writings that he fully understood its materialistic implications.

For instance, Darwin wrote:

“The view that each variation has been providentially arranged seems to me to make natural selection entirely superfluous, & indeed takes the whole case of appearance of new species out of the range of science.”2

“If I were convinced that I required such additions to the theory of natural selection, I would reject it as rubbish. … I would give absolutely nothing for theory of nat. selection, if it require miraculous additions at any one stage of descent.”3

Richard Dawkins commented on this aspect of Darwin’s theory, saying:

“In Darwin’s view the whole point of the theory of evolution by natural selection was that it provided a non-miraculous account of the existence of complex adaptations. … For Darwin, any evolution that had to be helped over the jumps by God was not evolution at all.”4

Also, Darwin of all people would have well known that large numbers of his followers had followed his lead in taking it to its logical materialistic, naturalistic (i.e. atheistic) conclusion. If he had indeed become converted, the ethical obligation on him to at least correct that idea, even if he himself still held to common descent/evolution, would have been overwhelming. So much so that it would have been unethical to the extreme to omit to do this in conjunction with his promotion of evolution. Clearly, his failure to do so while still promoting evolution casts further doubt upon the claim of a genuine conversion.

In short, it would seem exceedingly strange for Darwin to have thought it was OK to become a Christian, then promote evolution while neither refuting evolution nor dissociating himself from the atheistic implications he himself had promoted.

Update: 19 December 2013

A newspaper article published in The Pall Mall Gazette in September 1882 after Charles Darwin’s death has a telling quote in which he rejects revelation.

It reported that in answer to a student’s question in 1879, he wrote:

“I am very busy, and am an old man in delicate health, and have not time to answer your questions fully, even assuming that they are capable of being answered at all. Science and Christ have nothing to do with each other, except in as far as the habit of scientific investigation makes a man cautious about accepting any proofs. As far as I am concerned, I do not believe that any revelation has ever been made. With regard to a future life, every one must draw his own conclusions from vague and contradictory probabilities.”

References

- See Alfred Russel Wallace: Co-inventor of Darwinism, Creation 27(4):33–35, Sept. 2005. Return to text.

- Darwin to Lyell, Darwin Correspondence Project, Letter 3223 dated 1 August 1861. Return to text.

- Darwin to Lyell, Darwin Correspondence Project, Letter 2503 dated 11 October 1859. Return to text.

- Dawkins, R., The Blind Watchmaker, pp. 248-249, Penguin, London, 1991. Return to text.

References

- Croft, L. R., Darwin and Lady Hope: The Untold Story, Elmwood Books, PR5 4JF, England, 2012. Return to text.

- Moore, J., The Darwin Legend, Baker Books, Michigan, 1994. Return to text.

- Moore, p. 83. Return to text.

- Moore, p. 150. Return to text.

- Croft, pp. 25–28. Moore gives the same wording, pp. 92–93. Return to text.

- Croft, p. 25 Return to text.

- Moore, p. 91. Return to text.

- Moore, pp. 86, 88. Return to text.

- Croft, p. 67. Return to text.

- Croft, pp. 127 and 131, see also Moore, p. 85. Return to text.

- [sic] Return to text.

- Croft, p. 131. Return to text.

- Moore, p. 94. Return to text.

- Moore, pp. 166–67. Return to text.

- Croft, pp. 93, 138. Return to text.

- Moore, p. 143. Return to text.

- These exclusions were replaced by Darwin’s granddaughter Nora Barlow in 1958; see p. 6 of Barlow, N., Autobiography of Charles Darwin: With original omissions restored, Collins, London, 1958. Return to text.

- Croft, p. 30. Return to text.

- Moore, p. 145. I.e. as of 1994 when Moore’s book was published. Return to text.

- Moore, pp. 146. Return to text.

- E.g. Darwin’s comment that the biblical teaching of everlasting punishment was “a damnable doctrine”. See ref. 17, p. 87. Return to text.

- Moore, pp. 150–51. Return to text.

- Croft, pp. 133–34. But note that Lady Hope did not write that “he had returned to the Christian faith”. These words on p. 133 and again on p. 134 of ref. 1 are Croft’s own analysis. Return to text.

- Croft, pp. 108–09. Return to text.

- Croft, p. 109. Return to text.

- Darwin to Hooker, J.D., Darwin Correspondence Project, Letter 2345, dated 20 October 1858. Return to text.

- The full text is available in Darwin online, Aveling 1883. Return to text.

- This is consistent with what Darwin wrote in his Autobiography in 1876: “The mystery of the beginning of all things is insoluble by us: and I for one must be content to remain an Agnostic.” Ref. 17, p. 94. Return to text.

- See Life and Letters of Charles Darwin, 1887, Vol. 1, p. 317 note, for full report (available in Darwin online, Life and Letters.) Return to text.

- Moore, pp. 130–34. Moore gives the full text of this letter. Return to text.

- The word ‘book’ could refer to the Bible which Darwin was holding, but note that in the 1915 account Lady Hope says Darwin called Hebrews ‘the Royal Book’, Croft, p. 26. Return to text.

- Moore, p. 133. Return to text.

- Darwin to Hooker, J.D., Darwin Correspondence online, Letter 4065, dated 29 March 1863. Return to text.

- Here is the last sentence of The Origin of Species, 6th edition, 1872, p. 429: “There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into one, and that , whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being evolved.” Return to text.

- Croft, p. 126. Return to text.

- Unless the absence is particularly conspicuous or remarkable, as per note 5 in Jonathan Sarfati’s article Should we trust the Bible?, though that is not being claimed here. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.