Theistic evolution and the doctrine of death

It may seem strange to refer to death as a Christian doctrine, but the Bible is replete with teaching on the subject. Equally clear is the fact that the theory of evolution depends on death. Thanatology is the branch of theology dealing with doctrine of death, but it also refers to the scientific study of death—its forensic, psychological and social aspects. The following article is a chapter of the author’s book Evolution and the Christian Faith (2018), titled ‘A theory that requires death? Evolution and the doctrine of death’.

“As human beings, it is hard for us to shake the idea that our existence must have significance beyond the here and now. Life begins and ends, yes, but surely there is a greater meaning. The trouble is, these stories we tell ourselves do nothing to soften the harsh reality: as far as the universe is concerned, we are nothing but fleeting and randomly assembled collections of energy and matter. One day, we will all be dust” (Teal Burrell, 2017).1

“[Y]ou are dust, and to dust you shall return” (Genesis 3:19).

[God] knows our frame; he remembers that we are dust (Psalm 103:14).

The last enemy to be destroyed is death (1 Corinthians 15:26).

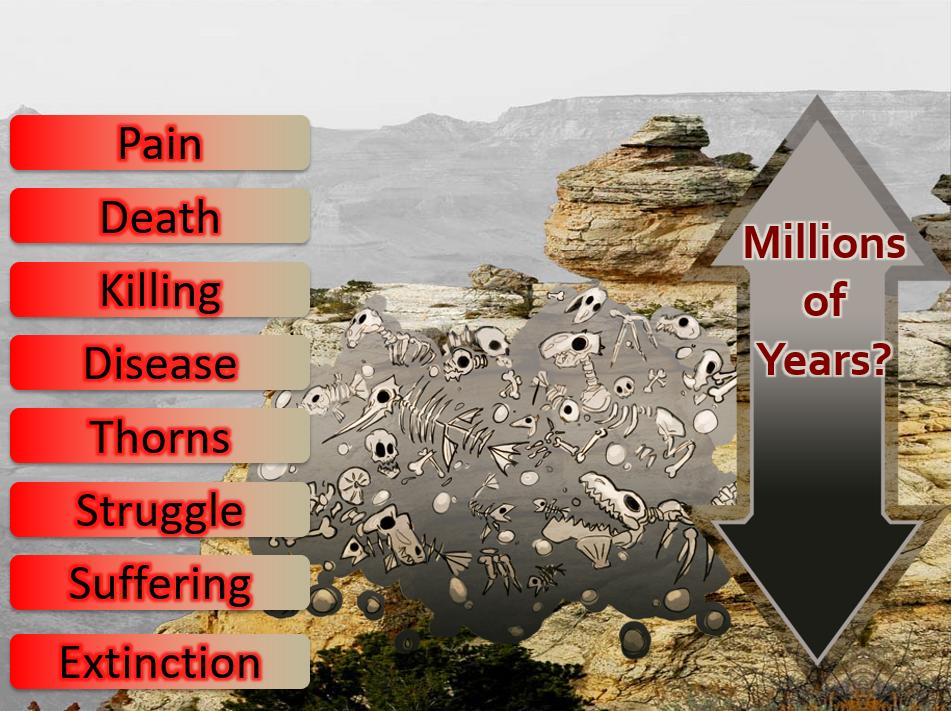

Belief in evolution can radically alter one’s concept of death. The whole creation/evolution debate revolves around the question of how God created. Was it by speaking things into existence ex nihilo, ‘out of nothing’ (see Hebrews 11:3)? Did He specially create unique kinds of living organisms upon the earth inside a single week? Or did God use evolution, spreading out this creative activity over hundreds of millions of years? If the latter, inevitably struggle, disease, violence and death would have been involved at every step along the way. At the heart of the origins debate, then, we must face the question, ‘Did God incorporate death into his creation from the very beginning?’

One of British author Jules Howard’s recent books was published with the intriguing title, Death on Earth: Adventures in evolution and mortality.2 The publisher’s website carries the following perspective in its advertising blurb:

Natural selection depends on death; little would evolve without it. Every animal on Earth is shaped by its presence and fashioned by its spectre. We are all survivors of starvation, drought, volcanic eruptions, meteorites, plagues, parasites, predators, freak weather events, tussles and scraps, and our bodies are shaped by these ancient events.3

In other words, the spectre of death, in all its various forms, haunts every creature that has ever lived, humans included. And if evolution is true, that is how things have been since time began. We will explore this relationship between evolution and death and consider the responses by theistic evolutionists to the problems posed. What about physical versus spiritual death of human beings? Is animal death to be distinguished from human death, or the death of plants and bacteria for that matter? Does it really matter? What does the Bible have to say? But before we get to those important questions, it will be helpful to remind ourselves of the stark reality of the subject before us, lest we forget its intensely practical and personal relevance.

Facing up to death

Occasionally we hear someone quip sardonically that, ‘nothing is certain except death and taxes’. The point of this proverbial statement, of course, is that the requirement to pay taxes is as inevitable as one’s death. Unquestionably, death is the ultimate statistic since 10 out of 10 people die. There is not the slightest probability of someone escaping their mortality. As the wise king Solomon famously declared, “For everything there is a season, and a time for every matter under heaven: a time to be born, and a time to die” (Ecclesiastes 3:1–2). Yet, death is a very unpopular topic for conversation—to bring it up at a party would be seen as a serious faux pas. Few, it seems, are comfortable with a serious conversation about death. And funerals are especially challenging occasions for many people.

For all of us, the most pressing question is whether we are ready to face death—do we have hope beyond the grave? Without Christ, we are without hope and without God in this world (Ephesians 2:12). But Christian people experience the difference that a living faith in Jesus makes when confronted with their own death or that of a fellow Christian. They do “not grieve as others do who have no hope” (1 Thessalonians 4:13). Of course, they do experience grief at the death of a loved one, friend or colleague, but they face it with the certain hope of eternal life beyond the grave.

In contrast, consider the sad case of the late Christopher Hitchens who, having failed in his fight against oesophageal cancer, died in 2011. An atheist, this celebrated writer and orator was known for his vitriolic criticism of people of faith, not least Christians. Some of his books—God is Not Great4 (2007) and The Portable Atheist (also 2007)—helped solidify his reputation as a spokesperson for opponents of biblical Christianity. A year before Hitchens passed away he was interviewed by well-known British journalist Jeremy Paxman.5 Asked if he feared death Hitchens replied, “No. I’m not afraid of being dead. That’s to say, there’s nothing to be afraid of; I won’t know I’m dead.”6

His confidence was unfounded for, “it is appointed for man to die once, and after that comes judgment” (Hebrews 9:27). Hitchens was well aware of the Bible’s teaching on this point but said he’d be surprised to find himself facing God’s tribunal. Like so many others, he was prepared to take the gamble that there was no conscious existence beyond his physical death. He despised the teaching of the Apostle Peter that, “there is salvation in no one else, for there is no other name under heaven given among men by which we must be saved” (Acts 4:12). He was prepared to take the chance that he had no soul that would exist after his death. Scripture, however, teaches that the soul is immortal, a person’s most precious possession (Mark 8:36–37).

Evolution and the ‘enemy of death’

Why this presumption and arrogance on the part of people like Hitchens? In the same interview, Hitchens admitted, “My view is already quite stark, which is that we’re born into a losing struggle … something meaningless or random. …it’s a stark existence.” This is a sober illustration of how people live out their lives in practical terms—a belief in the evolutionary struggle for existence certainly tends to make atheists of people.7 Yet, in spite of Hitchens’ claimed fearlessness regarding imminent death, others confess to more alarm. During the 1990s as a cancer researcher, I was interested to read about American evolutionist Stephen Jay Gould’s battle with mesothelioma.8 Diagnosed in the early 1980s, he had been completely cured. Sadly, 20 years later, he succumbed to an unrelated cancer of the lung which spread to his brain. He died in 2002, aged 60. During his first battle with cancer, he wrote:

It has become, in my view, a bit too trendy to regard the acceptance of death as something tantamount to intrinsic dignity. Of course I agree with the preacher of Ecclesiastes that there is a time to live and a time to die9—and when my skein runs out I hope to face the end calmly and in my own way. For most situations, however, I prefer the more martial view that death is the ultimate enemy—and I find nothing reproachable in those who rage mightily against the dying of the light (my emphasis).10

Yes, death is the ultimate enemy (a point to which we will return later). However, in the teeth of death, atheism is a dreadfully bleak, hopeless ideology.11 The nihilistic view of death advocated by both Hitchens and Gould, as they stared death in the face, was connected to their conviction that death and evolution go hand in hand. Yet the worldview of theistic evolutionists is little different from that of atheistic or agnostic evolutionists. Apart from the ‘addition’ of God as the Superintendent of natural selection, the stark picture of struggle, extinction and death is exactly the same. Surely this should give pause for thought. I have yet to hear anyone testify that, upon their conversion to belief in evolution, they gained a profound appreciation of the love of God. Or, that they received a confident hope in the face of death and the grave.

Death of the unfit

We have already considered the ‘problem of evil’ but it will be helpful to cover some similar ground before we examine the ways in which theistic evolutionists try to accommodate death into their vision of creation. Evolutionists who profess no faith often go out of their way to highlight this aspect of evolution. Janet Browne, British science historian and acclaimed biographer of Charles Darwin, has degrees in zoology and the history of science; she is Aramont Professor of the History of Science at Harvard University. In the documentary film Darwin: The Voyage that Shook the World, Browne is adamant:

Darwin … was working on a theory that requires death. His theory of natural selection is built on the idea that the unfit are going to die, that they are not going to contribute to the next generation” (italics added to match her own emphasis of speech).12

In the same film, Browne explains that Darwin’s own bereavement, involving three of his children, presented him with real difficulties. He could not reconcile his death-ridden theory with a God who would allow his beloved daughter Annie to die (aged just 10 years). Other biographers of Darwin agree that this tragic loss was the final death knell for any remaining vestiges of Darwin’s Christian faith. Weak in body, Annie had simply lost the struggle for existence—her death, excruciating though it was for him personally, was fully in accord with natural selection. This, after all, is precisely the sort of thing that evolution entails, in fact demands.

People often describe natural selection as ‘the survival of the fittest’. As discussed earlier (p. 104 of the book), this rather hackneyed term was coined by famous English philosopher and promoter of evolution, Herbert Spencer (1820–1903); Darwin liked it so much that he made it the heading of chapter 4 of the fifth edition of his The Origin of Species (1869). In reality, ‘death of the unfit’ and ‘survival of the fittest’ are simply two sides of the same coin. Again, to quote the man himself, from the closing paragraph of his book:

Thus, from the war of nature, from famine and death, the most exalted object which we are capable of conceiving, namely, the production of the higher animals, directly follows (my emphasis).13

Death is in the engine room of evolution by natural selection, a major driver in the process that supposedly optimises the survival of the organisms with the most advantageous characteristics. Indeed, without death to weed out the less fit and the unfit, there could be no survival of the fittest and no Darwinian evolution.

The ‘horridly cruel works of nature’

One often hears people remark that, “nature is so cruel”, or words to that effect. Sometimes it is posed as a question. Such comments are usually provoked by our morbid fascination over predators alluring, tracking, capturing and killing their prey, sometimes in ways which seem to maximise distress for the victim. That is not to say that we cannot appreciate the spectacle of the arms race between diverse predators and their prey, the sort of thing which plays out on our TV screens. Watching nature documentaries such as The Hunt14—which showcases such fascinating creatures as: tigers, lions, orcas, wolves, cheetahs, polar bears, blue whales, harpy eagles and more—one is constantly struck by the sheer beauty, agility, grace, speed, and ingenuity of both the predators and their prey. At the same time, many of us are also repulsed by the carnage which we observe. We cannot but empathise with the victim’s suffering, which inevitably is part and parcel of the kill.

As former Simonyi Professor for the Public Understanding of Science at Oxford University, Richard Dawkins is infamous for his vitriolic attacks on religion—especially conservative, evangelical Christian faith. In his book The Devil’s Chaplain, Dawkins quotes words which Charles Darwin penned to his friend Joseph Hooker, “What a book a Devil’s Chaplain might write on the clumsy, wasteful, blundering low and horridly cruel works of nature.”15 The doctrine of survival of the fittest as a creative mechanism (plus death of the unfit) was a subversive one for the people of Victorian times. Obviously Darwin was mindful of that fact. The way in which Dawkins apparently styles himself as the ‘Devil’s Chaplain’ is also interesting. Anyone familiar with his writings knows that he delights in highlighting the incompatibility of evolution’s ravages with Christian theism. Interviewed on a Dutch radio station, Dawkins declared:

Nature is cruel; not only is nature cruel, but it follows from Darwin’s theory of natural selection that nature is bound to be cruel, because even very beautiful things like a leopard, a lion, a cheetah or the antelopes that they hunt, they’re beautiful and beautifully designed to run fast because countless millions of cheetahs and antelopes have killed and died over many generations to make them so (my emphasis).16

Most will have to agree with Dawkins here, that nature in this sense is indeed cruel. Mind you, it must be admitted that the above words contradict what he himself had written in River out of Eden years earlier:

Nature is not cruel, only pitilessly indifferent. This is one of the hardest lessons for humans to learn. We cannot admit that things might be neither good nor evil, neither cruel nor kind, but simply callous—indifferent to all suffering, lacking all purpose.17

In fairness to Dawkins, though, his point is simply this: what appears to be cruel to you and me is actually nothing of the sort. There being no Creator God—which, as an atheist, he believes is virtually certain—concepts of good/evil, cruelty/kindness are meaningless. Nevertheless, in common with many of his fellow atheists, his observation of life’s bloody struggle for existence is a key plank in his armament against a Creator God:

The total amount of suffering per year in the natural world is beyond all decent contemplation. During the minute it takes me to compose this sentence, thousands of animals are being eaten alive; others are running for their lives, whimpering with fear; others are being slowly devoured from within by rasping parasites; thousands of all kinds are dying of starvation, thirst and disease. … The universe we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil and no good, nothing but blind, pitiless indifference (my emphases).18

There is only one watertight answer to this bleak, nihilistic outlook on life. People like Dawkins are looking at a fallen, sin-cursed world (Genesis 3:14–19; Romans 8:20–22) and assume that, from their evolutionary perspective, death and life have always gone hand in hand. Contrary to the bleak picture painted here, this world was designed by God and was originally “very good” (Genesis 1:31). Surely a world in which the ugliness of animal carnivory, parasitism, disease and death were unknown before the Fall (Genesis 1:29–30)? But, not according to the doctrine of theistic evolution (hereafter TE).

Death’s endorsement by Theistic Evolution

Let us briefly recall two quotations which we encountered earlier: “Natural selection depends on death; little would evolve without it”; and “Darwin … was working on a theory that requires death. His theory of natural selection is built on the idea that the unfit are going to die.” As strange as it may sound, these statements represent a profound insight (but one which often goes unrealised) about what Darwin’s idea really entails. Evolution is a philosophy of death, even a eulogising of it. In view of all that we have encountered in the writings of prominent evolutionists thus far, it should hardly be in doubt.

But many Christians have not grasped the stark fact that death is firmly anchored within the evolutionary worldview. Without death, there could be no life. And if TE is true, this was how God always intended things to be. In which case, God would have employed death, which according to the Apostle Paul is “the last enemy” (1 Corinthians 15:26), as one of his “very good” agents of Creation (Genesis 1:31). In evolutionary terms, death is a vital component—we could say with some justification that death is a contributory creator of life. Jack Mahoney explains:

… whereas in traditional Christianity death has always been perceived as a penalty [for sin], in evolution through natural selection the death of individuals, not just of humans, is rather seen as a biological necessity and a requirement [for life].19

Intuitively, upon realising that death so characterises evolution, many Christians baulk at evolution as God’s mode of creation. Certainly, this was true of my own spiritual journey. A one-time theistic evolutionist myself, a day came when the sudden realisation that death was a prerequisite of evolution hit me between the eyes. Immediately, I rejected the remaining vestiges of my evolutionary worldview, embracing instead a literal understanding of Genesis 1–3; the impact of that decision on my faith was truly liberating (John 8:32). For other people, the dawning realisation that evolution necessitates death leads, instead, to their rejection of Genesis as a historical narrative of events that really took place. Some of this second group adopt TE but many others reject Christianity altogether as unworkable, built, as they have come to understand it, on mere ‘legendary quicksands’ (see first quotation in this article). Those who shun faith in this way are unable to stomach the necessary reconciliation with death that TE requires.

We began by observing that the creation/evolution question is partly over how God created. Was death vital to his methodology? Theistic evolutionist Denis Alexander says, “One thing is clear: the only proper answer to the question ‘How does God interact with the world?’ is ‘At all times, in all places and in every way’.”20 On that point we wholeheartedly agree. Indeed, he goes on to quote Paul’s words to Athenian philosophers (Acts 17:25–28) which affirm these truths. So far, so good. This active involvement of God in his creation (what theologians call God’s immanence21) means that God is fully responsible for its exact nature in the beginning—he did not simply ‘light the blue touch paper’ (perhaps some sort of big bang), then retire and allow events to unfold. However, TE recognises no physical discontinuity (no break in the natural order) at Adam’s Fall. Therefore today’s status quo, as far as death and suffering are concerned, is also the pre-Fall status quo. Predictably, Alexander continues, “If the immanence of God in the created order means anything, then it means God’s working through all the processes of the evolutionary process without exception… In other words, God is the author of the whole story of creation, not just bits of it.”22

Now that does pose a problem for it means that, for theistic evolutionists like Alexander, “God is the author” of death as a creative process. Alexander does not shirk this charge. Like all other theistic evolutionists, he asserts that it is only spiritual death which the Bible is referring to in the passages which relate to the Fall and the Curse. Again we must emphasise that Alexander is no Deist, although the views of some theistic evolutionists do sound more like Deism. As already mentioned, his concept of God is not a being who, in the beginning, wound up the universe like a clock, then left it to unfold according to universal laws which he had first instituted. No, he embraces fully all forms of physical death as an intentional part of God’s created order:

Nowhere in the Old Testament is there the slightest suggestion that the physical death of either animals or humans, after a reasonable span of years, is anything other than the normal pattern ordained by God for this earth.23

We will answer his challenge later. For now, we note that this teaching about death is the standard teaching of TE. Tom Ambrose is an English Anglican clergyman with a background in geology. As an ardent theistic evolutionist, his views demonstrate the ‘slippery slope’ nature of such reasoning:

Fossils are the remains of creatures that lived and died for over a billion years before Homo sapiens evolved. Death is as old as life itself by all but a split second. Can it therefore be God’s punishment for Sin? The fossil record demonstrates that some form of evil has existed throughout time. On the large scale it is evident in natural disasters. … On the individual scale there is ample evidence of painful, crippling disease and the activity of parasites. We see that living things have suffered in dying, with arthritis, a tumour, or simply being eaten by other creatures. From the dawn of time, the possibility of life and death, good and evil, have always existed. At no point is there any discontinuity; there was never a time when death appeared, or a moment when the evil [sic] changed the nature of the universe. God made the world as it is … evolution as the instrument of change and diversity.24

Notice, not only does Ambrose embrace death from the dawn of time, but evil as well. No prizes for guessing which authority he most reveres. Evolution is allowed to trump the Bible. Scripture, in his thinking, must bow the knee to the ‘science’—which really means his philosophy—of evolution and millions of years. As the next chapter of this book demonstrates, his statements are a subversion of the truth and profoundly impact our understanding of the Gospel.

Convoluted Bible readings

A number of theistic evolutionists know which verses and passages of Scripture are used by historic special creationists (biblical creationists) to affirm the absence of pre-Fall death. Many authors, therefore, attempt to stifle or diffuse those challenges to TE. Yet, for all the erudition and sophisticated reasoning they employ, one rather obvious flaw runs as a common thread through their writings. They fail to acknowledge, let alone engage with, the obvious acceptance of Genesis 1–11 as historical narrative by Jesus, and the apostles and writers of the New Testament. After all, these people insisted on the historical reality of the people, events and places recorded there, including original perfection before the Fall. As we saw previously (chapters 3 and 4 of the book), the only way around this difficulty—and some have gone a long way down this road—is to argue that the New Testament writers were wrong, just men of their day and age.

But, that aside, let us consider more carefully Denis Alexander’s words (representative of theistic evolutionists generally), “Nowhere in the Old Testament is there the slightest suggestion that the physical death of either animals or humans, after a reasonable span of years, is anything other than the normal pattern ordained by God for this earth.” Not the slightest suggestion? Not even in God’s words “very good” at the end of his creative work? To get an idea of just how subversive this claim is, think about these words: “And to every beast of the earth and to every bird of the heavens and to everything that creeps on the earth, everything that has the breath of life, I have given every green plant for food” (Genesis 1:30). Since this verse teaches a total absence of animal carnivory in that pristine world, it provides more than a slight suggestion that the physical death of animals is not normal. Considered alongside God’s declaration of the moral and physical perfection of all that He had made originally (the meaning of the Hebrew for “very good” in Genesis 1:31), the absence of pre-Fall death seems to be beyond reasonable doubt. The argument for the physical death of animals being entirely “normal”, let alone “ordained by God”, sounds like a straight denial of the text of Genesis.

But there is more. Adam was given clear instructions by God on the day of his creation, “And the Lord God commanded the man, saying, ‘You may surely eat of every tree of the garden, but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat, for in the day that you eat of it you shall surely die’ ” (Genesis 2:16–17; my emphasis). Later, having wilfully flouted God’s command concerning that particular tree—for “Adam was not deceived” (1 Timothy 2:14)—God dealt with him accordingly: “And to Adam he said, ‘Because you … have eaten of the tree of which I commanded you, “You shall not eat of it,” cursed is the ground because of you; in pain you shall eat of it all the days of your life; … By the sweat of your face you shall eat bread, till you return to the ground, for out of it you were taken; for you are dust, and to dust you shall return’ ” (Genesis 3:17, 19; my emphases).

The warning, “you shall surely die”, is fulfilled by the penalty, “to dust you shall return”. That ‘a return to dust’ refers to physical death seems clear. That being the case, one would think that God’s warning of certain death in Genesis 2:17 must surely refer to physical death too, not merely spiritual separation from God. While Adam’s physical death was not immediate, he did not avoid the penalty of his disobedience, eventually dying at the age of 930 years (Genesis 5:5)—but he died spiritually the very day that he ate the forbidden fruit.

Just as various models of ‘Adam and Eve’ are held by different theistic evolutionists, there are differences in the way they model the Fall. Nevertheless, all versions of TE envisage physical death pervading the entirety of evolutionary history—without that, evolution would be a no go, as we have seen. Treating the early chapters of Genesis as history is not possible within a TE framework; instead they are taken figuratively. Thus, Alexander, in common with most other theistic evolutionists, asserts that the penalty for Adam’s sin was not physical but spiritual death, “Here in Genesis 3 the passage is quite clear that Adam and Eve died as a result of their sin, just as God had warned, but they died spiritually.”25

How does this claim square with the actual texts before us (Genesis 2:16–17; 3:17, 19)? On pain of death, God had warned Adam of the consequences of disobediently eating fruit from the forbidden tree: “you shall surely die” (Genesis 2:17). The Hebrew literally means, “dying you shall die” (see discussion here). The penalty of disobedience for Adam and Eve (and their descendants) would be a process of physical decline ending in physical death. Without doubt, spiritual death (separation from God) occurred the moment that they sinned. However, this verse cannot be pressed to mean spiritual death alone without making a nonsense of the Hebrew. Quite clearly, the verse is not teaching: ‘Adam, the moment you sin, you will begin to die spiritually until, eventually, you are spiritually dead.’ Moreover, God reminded Adam of his words of warning in passing sentence on him: Adam would “return to the ground … to dust you shall return.” This statement employs very misleading language if it is not meant to convey physical death at all, just spiritual death. Again, as with the case for animal death, there is more than a slight suggestion here that the physical death of humans is abnormal.

During the ‘committal’ of a funeral service, when the minister says, “For [God] knows our frame; he remembers that we are dust” (Psalm 103:14; my emphasis), nobody doubts that our physical mortality is in view. At the graveside, the object lesson is even more poignant, as the minister says, “we now commit [name of the deceased]’s body to the ground: earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust …”26 Try telling someone witnessing a burial that the physical death of the deceased is not especially in view! The words “ashes to ashes” are inspired by Ezekiel 28:18, “I turned you to ashes on the earth in the sight of all who saw you”, while “dust to dust” is, of course, a reference to Genesis 3:19.

Puzzlingly, Alexander does say that God, “is seen as the direct agent in the death of animals in Psalm 104:29 when he ‘takes away their breath’ so that ‘they die and return to the dust’.”27 Clearly, animals cannot die spiritually so Alexander is definitely using this verse to teach that animals die physically. He contends that their death has been the normal state of things from the dawn of animal origins. However, the very words he quotes from the psalm are a fitting reminder of God’s words to Adam in Genesis 3:19. Animals “return to the dust”—physical death; here Alexander agrees. Adam the guilty sinner is told he will “return to the ground, … to dust you shall return”—physical death; but here Alexander disagrees. In fact, Alexander has this to say:

The reminder to the man that he will return ‘to the dust’ (verse 19) seems not to be a consequence of his disobedience, but rather a reminder that sweating away to extract crops from the earth is actually quite appropriate when we recall that Adam is destined to return to the earth anyway.28

Such a fanciful interpretation weaves a tangled web indeed. Moreover, it is a violation of the principle that Scripture is perspicuous, that is, clearly expressed and readily understood. It amounts to a denial of what the text of Genesis 3:19 manifestly teaches, that Adam’s sin was the occasion of both his spiritual and physical death. Later in this book (chapter 10), we will unpack this further in considering the nature of the Curse and its eventual removal (Revelation 22:3).

Arguing from such passages as Job 24:19 (life snatched from sinners in Sheol, the place of the dead), 2 Kings 20 (Hezekiah’s delayed death), and 2 Samuel 12 (the death of David’s son through his adultery with Bathsheba), Alexander says, “It is clear from these contexts that it is not death per se which is caused by sin, but rather premature death which is seen as specific punishment for specific sins.”29 Be that as it may, those passages of Scripture have nothing whatsoever to say about the ultimate reason for death. They are of zero relevance in determining the truth about the consequences of Adam’s sin. In all these cases, such a convoluted approach to Scripture interpretation is not easy to follow. Why such apparently tortuous reasoning? Is it not because, given the insistence upon TE, physical death must have been happening for millions of years before the Fall of mankind?

Turning to the New Testament, it is true that many passages focus especially upon spiritual death (although the physical and spiritual aspects of death are closely intertwined). Nevertheless, other New Testament passages especially affirm its physical aspect (e.g. 1 Corinthians 15:35–36, 42–44, 53; 2 Corinthians 5:1–4). This is in agreement with a grammatical-historical interpretation of Genesis (see chapter 1, the section entitled Rightly interpreting the Bible). That Adam’s sin resulted in his spiritual separation from God (spiritual death) is hardly controversial. But the contention that the Fall was not responsible for the intrusion of physical death is as unconvincing as it is a denial of a plain reading of the text.

This is not merely an academic argument. Christians have the wonderful prospect of glorious resurrection bodies and this expectation grows as their physical frames become ever frailer and more diseased with advancing age. Their increasing decrepitude is the harbinger of their final decease physically. Down here, there is groaning; they are becoming an increasing burden to themselves. All is the fruit of sin and the Curse. But their hope, praise God, is ‘up there’ where, in the presence of their Saviour, mortality will give way to immortality and eternal life (2 Corinthians 5:4).

Scripture sanely explained

In direct contrast to the Bible revisionism observed in TE writings, we must view this whole question of death through the undistorted lens of Scripture. Doing so, we confidently affirm that physical death is a consequence of spiritual death. We cannot drive a wedge between the two. Try as some theistic evolutionists might, they simply cannot have one without the other. In such well-known passages as Romans 5:12–17, we learn that, “sin came into the world through one man, and death through sin”, and that from Adam onwards, “death reigned”. Of course, human death is particularly in view here. Paul teaches, “by a man came death” and, lest there should be any doubt as to this man’s identity, he elsewhere clarifies that, “in Adam all die” (1 Corinthians 15:21–22).

People all die because of Adam’s sin and also because of their own sin. Referring to Paul’s words, “because of one man’s trespass, death reigned through that one man” (Romans 5:17), Thomas Schreiner points out:

Death reigns as a power over those who are in Adam, for death is not merely an event that occurs but a state in which human beings live as a result of Adam’s sin. … death can’t be limited to spiritual or physical death, for both realities are designated by the word “death.” … Clearly, Adam is the fountainhead for sin and death in the world.30

No Christian of the first century would have assumed Paul was referring only, or even primarily, to spiritual death. The words he used (inspired by the Holy Spirit) are too plain for that.

We use the word ‘reign’ to describe a monarch sovereignly ruling over a people. It carries with it the idea of dominion, even of subjugation. The Bible presents us with two contrasting reigns. There is, firstly, the reign of death. Here ‘reign’ clearly conveys death’s absolute supremacy. Everyone is fully under its sway as one of its subjects. Death is the worst foe we can possibly meet, the ultimate enemy of us all—nobody can hope to escape its total dominion. With the exception of two special cases—Enoch (Genesis 5:24) and Elijah (2 Kings 2:1, 11)—physical death has had the mastery over all human beings that have ever lived. And, with the further exception of Jesus (fully God as well as fully human), this has been mankind’s lot ever since Adam’s Fall.

Then secondly, there is the reign of Christ, “For he must reign until he has put all his enemies under his feet. The last enemy to be destroyed is death” (1 Corinthians 15:25–26; my emphasis). Paul’s epistles make clear that genuine repentance and faith in Christ result in people being “made alive” spiritually (1 Corinthians 15:22). They have been converted and are now Christians. No longer need they fear the grave. One day they will exchange their perishable bodies for immortal ones (1 Corinthians 15:53–55)—a physical renewal. Spiritually speaking, death’s reign over Christians ends at their conversion. Physically, death’s dominion is terminated when they leave behind their perishable bodies to be with Christ (2 Corinthians 5:8, Philippians 1:23).

The confidence of believers is in the One who vanquished death at the cross and was resurrected. As “the Author of life” (Acts 3:15), Jesus has power over death itself (see Revelation 1:18). He said, “I lay down my life that I may take it up again. No one takes it from me, but I lay it down of my own accord. I have authority to lay it down, and I have authority to take it up again. This charge I have received from my Father” (John 10:17–18). Death, “the last enemy”, will be destroyed—its reign finally and forever over (1 Corinthians 15:26). We might well ask, if death was part of God’s ‘good’ creation and not the result of Adam’s sin, why did Christ come into the world? Why undo what He had done in the first place? And why did Paul call death an ‘enemy’ if it was part of the good creation?

Just as death had no dominion over Christ Jesus, the sinless Son of God, it could have had no power over Adam in his pre-Fall perfection. When Jesus died at Calvary He was willingly making himself a sin offering (2 Corinthians 5:21). In so doing, He brought himself under the penalty of sin, namely death—clearly his physical death is involved here.31 Even so, once He had disarmed the evil principalities and powers (Colossians 2:15), death was powerless to hold him and He was able to take his life again, rising bodily from the dead. As the pure and faultless one, Christ (the last Adam) could not die, except by becoming a sin offering. So, too, the first Adam (a type of Christ) was unable to die (either spiritually or bodily) so long as he remained in perfect obedience to God. Scripture teaches, “The soul who sins shall die” (Ezekiel 18:20), the obvious implication being that sinless souls do not die.

So far, we have distinguished spiritual from physical death of human beings. The Bible also speaks of “the second death” of people who have rejected Christ; tragically, their final destination, together with the devil and his minions, will be the lake of fire (Revelation 20:14, 21:8). That is beyond the scope of our present discussion except to affirm that no Christian need fear being hurt or conquered by the second death (Revelation 2:11; 20:6). All God’s saints will share in the resurrection and enjoy eternal life.

These scriptural teachings are not just interesting theological musings. As we saw earlier, illustrated by the pitiful statements of men like Christopher Hitchens and Stephen Jay Gould, such profound truths are relevant to everyone. Few people are truly reconciled with death, either their own or that of their loved ones. Most will agree with the Apostle Paul, as Gould did, that death is the last (ultimate) enemy. For non-believers, it is physical death that they view as the last enemy. However, both physical and spiritual death are included in Paul’s words. The contention, by theistic evolutionists such as Denis Alexander, that death is “the normal pattern ordained by God for this earth” fails the test of Scripture itself and violates most people’s common-sense understanding of their last enemy.

Animal death before Adam’s Fall?32

So, what of animal death? Is this not intrinsically different from that of human beings? And even if there was no predation originally, or even death through old age, might they not have died accidentally? What about the death of plants, or bacteria or fungi for that matter? Even assuming that humans were created ‘deathless’ originally, surely death prevailed in the animal kingdom? Influenced by TE or by supposedly unassailable scientific proof for millions of years, many Christians argue in this way. We can phrase the question a little differently. If, as virtually all evangelicals believe, there will be no animal death in the restored new earth to come (see chapter 10)—whether through old age, predation or accidents—was there animal death in Paradise (the world before the Fall)?

Firstly, it is worth noticing that the carcasses of dead animals are something which most people naturally find revolting. We generally go out of our way to avoid physical contact with such things. In the Old Testament, a person became defiled by touching the dead body of a wild animal. This is made explicit in many places (for example, Leviticus 5:2, 7:21, 11:8, 24–28, 39–40; Deuteronomy 14:8). In other words, animal death was considered unnatural. This negative attitude revealed in the laws given to Moses is best explained if the death of animals was not part of the original creation.

Secondly, as we have seen, every kind of wild animal, flying creature and creeping creature was intended to eat plants originally, with the emphatic “And it was so” (Genesis 1:29–30). All was “very good” in God’s estimation (Genesis 1:31), which does appear incompatible with the ugliness, suffering and pain of animal death. Scripture has much more to say. It teaches that “the life of the flesh is in the blood” (Leviticus 17:11). Animals that the Bible describes as having the ‘life principle’ (nephesh in Hebrew) are both air (nostril) breathers (Genesis 7:22) and ones with blood coursing through their veins. Certainly this includes all birds, reptiles and mammals. Similarly, Adam became a “living soul”, a “living being” (in Hebrew, nephesh chayyāh33) when God breathed his spirit into him (Genesis 2:7; 1 Corinthians 15:45). The pre-Fall death of such animals, then, is ruled out by association since they are also described as nephesh chayyāh in Genesis 1.

God’s words to Noah just after the Flood are also pertinent here: “But you shall not eat flesh with its life, that is, its blood. And for your lifeblood I will require a reckoning: from every beast I will require it and from man. From his fellow man I will require a reckoning for the life of man” (Genesis 9:4–5). God regards the life-blood as closely tied up with the life of a human being. Again, since nephesh animals are exactly like us in this regard, there is simply no scriptural warrant for the pre-Fall bloodshed of such animals.

However, even if death by carnivory (or sickness) is ruled out, might not the Bible allow for pre-Fall death that does not involve suffering? It is important to be clear at this point that the biological death of plants and single cells is not death in the biblical sense. After all, every sort of plant was intended for food in that state of Edenic perfection. Both people and animals were given fruit and vegetables for food (Genesis 1:29–30). In fact, the ‘death’ of plant cells, various fungi, and bacteria (a natural part of the gut flora of many animals, including ourselves), must have been a necessary and natural part of God’s created order. Digestion of plant matter, then, would have resulted in biological cell ‘death’, the nutrients released from these foods being a vital source of sustenance.

Even within animal bodies (but also known within all other organisms), an entirely natural cell-breakdown process occurs. Without it, normal growth and specialisation of body tissues would be impossible. This process of cell removal, termed ‘apoptosis’, involves numerous proteins. Each is programmed by the cell’s DNA to play its part in a sophisticated choreography of interactions—the cell is deconstructed and its components recycled for future use. Not surprisingly, apoptosis can go wrong in our fallen world, causing a host of diseases such as cancer and leukaemia. This is something I studied for many years as a cancer researcher.34 Originally, however, this must have been a perfect system and would have played a vital role in all multicellular creatures, as I have explained in detail elsewhere (also here).35 We can say that not all biological ‘death’ is really death in the biblical sense.

But could there have been pre-Fall animal death that was due merely to advanced age—death by ‘natural causes’? The answer is that animal death is clearly unnatural today, which is why many human beings feel grief even for an animal that dies. I have observed children (and even adults) grieving over deceased pets on many occasions. Whether a humble mouse or a beloved cat or a dog, the animal’s death invokes a deep sense of loss. Also, the stiffening of the body that follows for a period soon after death (rigor mortis) is unpleasant and disturbing. When my children were younger, I sometimes used the grief associated with their pet’s demise to teach that death was not God’s intention for creatures originally—a lesson that was not difficult to put across.

Some people ask why animals die at all if they cannot sin? A related question, sometimes put forward as a challenge to the doctrines of biblical creation and a historical Fall, is whether it is fair that animals should suffer the consequences of Adam’s sin. However, since God gave Adam dominion over all living creatures (Genesis 1:26, 28), his rebellion was the occasion for their downfall too—indeed that of the whole creation (Romans 8:20–22). The tragic fact is that living things all shared in the pollution and defilement brought about by the Fall. Indeed, our observation of the suffering and death of animals should act as a monument to human rebellion in Adam. Speaking of this, sixteenth century reformer John Calvin wrote, “And this all tends to inspire us with a dread of sin; for we may easily infer how great is its atrocity, when the punishment of it is extended even to the brute creation.”36

Concluding thoughts

Darwinian evolution is a philosophy which is impossible to reconcile with the biblical teaching on death, as theistic evolutionists must endeavour to do. God is the Author of life. Death and all that accompanies it—bloodshed, extinctions, mutations, diseases and untold suffering—is an unwelcome intruder into this world. The creation now ‘groans’ under the weight of thousands of years of the Fall and the Curse. This will continue until the time when the Curse is removed (Revelation 22:3). Only in the new heaven and earth will death, mourning, crying and pain cease at last (Revelation 21:1, 4).

The respected British journalist and television presenter Andrew Marr discussed the Darwinian implications for Life and Death in a programme with that very title. Commenting on Darwin’s worldview, he said, “But burdened by his thoughts of life and death, and extinction, [Darwin] soon began to retreat from the limelight. He knew that he had the seed of a dangerous idea, one that would undermine the Bible and Christian teaching” (my emphasis).37 Dangerous indeed. Logically, the dog-eat-dog, death-ridden view of life’s ultimate origins leads to nihilism. No surprise then, that among young people (in their teens and twenties), suicide is the leading or second-leading cause of death in some western countries.38 If people believe that they owe their existence to a process of death and struggle and are heading for more of the same, ending their lives prematurely can seem rational. This was the reasoning of a young man, Gerard, on Australian radio:

… I think that some people may have an inability to cope, and maybe this might sound a bit extreme, but that might be Darwinian theory, the Darwin theory of survival of the fittest. Maybe some of us aren’t meant to survive, maybe some of us are meant to kill ourselves … There’s too many people in the world as it is. Maybe it is survival of the fittest, maybe some of us are meant to just give up, and maybe that would help the species.39

Confessions like this are a tragic indictment of evolution’s impact on society. Surely it ought to engender some soul-searching among those who advocate TE. The sobering words of the prophet Jeremiah seem appropriate, “Cursed is the man who trusts in man and makes flesh his strength, whose heart turns away from the LORD… Blessed is the man who trusts in the LORD, whose trust is the LORD” (Jeremiah 17:5, 7). We have seen that evolution’s very mechanism requires death to weed out the less fit. But a philosophy which assigns creative powers to people’s mortal enemy is one which radically alters their conception of death. It gives many a ‘justification’ for turning away from God. The antidote is to return to a thoroughly biblical understanding of sin and death, that which is clearly revealed by the inspired writers of the New Testament. They treated the pertinent events of Genesis 1–3 as historical facts upon which they enthusiastically proclaimed the Gospel.

References and notes

- Burrell, T., A meaning to life: How a sense of purpose can keep you healthy, newscientist.com, 25 January 2017. Return to text.

- Howard, J., Death on Earth: Adventures in evolution and mortality, Bloomsbury Sigma, London, 2016. Return to text.

- Bloomsbury Publishing, Death on Earth, bloomsbury.com; accessed 1 August 2017. Return to text.

- The British edition of this book was subtitled, The case against religion. The American edition was subtitled, How religion poisons everything. Return to text.

- For a more detailed perspective on this interview, see: Bell, P., Christopher Hitchens: Staring death in the face, creation.com/facing-death, 22 December 2011. Return to text.

- Paxman meets Hitchens: A Newsnight Special, BBC Two, broadcast 29 November 2010. Return to text.

- Sarfati, J., Evolution makes atheists out of people!, creation.com/makes-atheists, 17 February 2015. Return to text.

- A cancer that commonly attacks the pleural layers of tissue around the lungs; less commonly it affects the peritoneum, a layer of abdominal tissue which surrounds various organs of the digestive system. Return to text.

- In fact, he slightly misquoted Scripture here for Ecclesiastes 3:1–2 reads, “For everything there is a season, and a time for every matter under heaven: a time to be born, and a time to die…” (my emphasis). Return to text.

- Gould, S.J., The median isn’t the message, Discover, June 1985. Return to text.

- Gould preferred to be described as an agnostic, although some of his closest friends and associates considered him an atheist. Nevertheless, he did acknowledge the faith of many of his colleagues. Return to text.

- Darwin: The Voyage that shook the world, DVD documentary movie, Fathom Media, for Creation Ministries International, 2009. Return to text.

- Darwin, C., On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life, 1st edition, John Murray, London, 1859, p. 490. Return to text.

- Attenborough, D. (Narrator), The Hunt: Nothing is certain, BBC One. In six-parts, part 1 was first screened on 1 November 2015. Return to text.

- Darwin, C., Letter to his friend and botanist, Joseph D. Hooker, 13 July 1856, www.darwinproject.ac.uk. Return to text.

- Noorderlicht Radio, 18 May 2004, noorderlicht.vpro.nl. Quoted from a transcript of the programme made at that time; see: Bell, P., The humanist apostles’ creed—that which ‘a Devil’s Chaplain might write’, creation.com/the-humanist-apostles-creed, 4 October 2004. Return to text.

- Dawkins, R., River out of Eden: A Darwinian view of life, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 1995, p. 96. Return to text.

- Dawkins, River Out of Eden, ref. 17, pp. 131–133. Return to text.

- Mahoney, J., Christianity in Evolution: An exploration, Georgetown University Press, Washington DC, 2011, p. 63. Return to text.

- Alexander, D., Creation or Evolution: do we have to choose? 2nd edition, Monarch Books, Oxford, UK, 2014, p. 218. Return to text.

- There is an overlap with the related idea of providence, God’s intervention, protective care and orchestration of the affairs of human beings. Return to text.

- Alexander, Creation or Evolution, ref. 20, p. 219. Return to text.

- Alexander, Creation or Evolution, ref. 20, p. 308. Return to text.

- Ambrose, T., ‘Just a pile of old bones’, The Church of England Newspaper, 21 October 1994. Return to text.

- Alexander, Creation or Evolution, ref. 20, p. 324. Return to text.

- The outline order for funerals, Book of Common Prayer, churchofengland.org/prayer-worship/worship/texts/pastoral/funeral/funeral.aspx. Return to text.

- Alexander, Creation or Evolution, ref. 20, p. 308. Return to text.

- Alexander, Creation or Evolution, ref. 20, p. 326. Return to text.

- Alexander, Creation or Evolution, ref. 20, p. 310. Return to text.

- Schreiner, T.R., Original Sin and Original Death, chapter 13 of: Madueme H. & Reeves M. (Eds.), Adam, The Fall, and Original Sin: Theological, biblical, and scientific perspectives, Baker Academic, Grand Rapids, MI, 2014, p. 284. Return to text.

- The whole question of whether Jesus died spiritually at his crucifixion is well beyond the scope of our present discussion but the following article is a helpful place to begin: Stegall, T.L., Did Christ die spiritually and physically? Grace Family Journal 86, Summer 2017; gracegospelpress.org, accessed 3 August 2017. Return to text.

- This section is developed from: Bell, P., The problem of evil: pre-Fall animal death? creation.com/pre-fall-animal-death, 29 March, 2011. Return to text.

- In the original Hebrew, נֶפֶשׁ חַיָּה. Return to text.

- Cell apoptosis is pictured and discussed in: Bosanquet, A.G. & Bell, P.B., Enhanced ex vivo drug sensitivity testing of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia using refined DiSC assay methodology, Leukemia Research 20(2):143–153, 1996. Return to text.

- Bell, P., Apoptosis: Cell ‘death’ reveals Creation, Journal of Creation 16(1):90–102, April 2002. Return to text.

- Calvin, J., A Commentary on Genesis, The Banner of Truth Trust, Edinburgh, UK, 1965, p. 250. Return to text.

- Life and Death, the third of three programmes, was first screened on 17 March 2009. For a review of this series see: Bell, P., The BBC TV series Darwin’s Dangerous Idea, creation.com/dangerous-idea, 29 April 2009. Return to text.

- For example, recently published figures show this to be true of the UK, Australia and the USA: Anon, Suicide, Mental Health Foundation (UK), mentalhealth.org.uk, 2016; Anonymous, Suicide in Australia, Australian Bureau of Statistics, abs.gov.au, September 2017; VanOrman, A. & Jarosz, B., Suicide replaces homicide as second-leading cause of death among U.S. teenagers, Population Reference Bureau, prb.org, June 2016. Return to text.

- Black Dog Days—The experience and treatment of depression, Life Matters with Norman Swan, ABC (Australia) Radio, 4 May 2000. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.