Journal of Creation 19(2):67–73, August 2005

Browse our latest digital issue Subscribe

The Christian foundations of the rule of law in the West: a legacy of liberty and resistance against tyranny

Abstract

According to the tradition of the rule of law in the West, to be under law presupposes the existence of certain laws serving as an effective check on arbitrary power. The rule of law is therefore far more than the mere existence of positive laws, as it also requires the state to act in accordance with principles of a ‘higher law’. The search for such ‘higher law’ implies, however, a moral discussion on what laws ought to be. If so, the rule of law becomes an impracticable and even undesirable achievement for societies not subject to certain patterns of cultural and religious behaviour. On the other hand, any radical change in such patterns can certainly produce undesirable consequences for the realization of the rule of law.

The Bible has been historically recognized as the most important book for the development of both the rule of law and democratic institutions in the Western world. However, we have seen over these last decades a deep erosion of individual rights, with the growth of state power over the life and liberty of individuals.

If the future we want for ourselves and our future generations is one of freedom under law, not absolute subjection to the arbitrary will of human authorities, we will have to restore the biblical foundations for the rule of law in the Western world. As such, the rule of law talks about the protection of the individual by God-given liberties, rather than by an all-powerful, law-giving government endowed by god-like powers over the civil society.

Christianity and the discovery of the individual

The modern roots of our individual rights and freedoms in the Western world are found in Christianity. The recognition by law of the intrinsic value of each human being did not exist in ancient times. Among the Romans, law protected social institutions such as the patriarchal family but it did not safeguard the basic rights of the individual, such as personal security, freedom of conscience, of speech, of assembly, of association, and so forth. For them, the individual was of value ‘only if he was a part of the political fabric and able to contribute to its uses as though it were the end of his being to aggrandize the state’.1 According to Benjamin Constant, a great French political philosopher, it is wrong to believe that people enjoyed individual rights prior to Christianity.2 In fact, as Fustel de Coulanges put it, the ancients had not even the idea of what it means.3

In 390, Bishop Ambrose, who was located in Milan, forced Emperor Theodosius to repent of his vindictive massacre of seven thousand people. The fact indicates that under the influence of Christianity, nobody, not even the Roman emperor, would be above the law. And in the thirteenth century, Franciscan nominalists were the first to elaborate legal theories of God-given rights, as individual rights derived from a natural order sustained by God’s immutable laws of ‘right reason’. For medieval thinkers, not even the king himself could violate certain rights of the subject, because the idea of law was attached to the Bible-based concept of Christian justice.

Christianity, the rule of law, and individual liberty

The notion that law and liberty are inseparable is another legacy of Christianity. Accordingly, God’s revealed will is regarded as the ‘higher law’, and therefore placed above human law. Then liberty is found under the law, God’s law, because as the Bible says, ‘the law of the Lord is perfect, reviving the soul’ (Psa 19:7). If so, people have the moral duty to disobey a human law that perverts God’s law, for the purpose of civil government is to establish all societies in a godly order of freedom and justice.

St Augustine of Hippo once wrote that an unjust law is a contradiction in terms. For him, human laws could be out of harmony with God’s higher laws, and rulers who enact unjust laws were wicked and unlawful authorities. In The City of God, St Augustine explains that a civil authority that has no regard for justice cannot be distinguished from a band of robbers. ‘Justice being taken away, then, what are kingdoms but great robberies? For what are robberies themselves, but little kingdoms?’4

In the same way, St Thomas Aquinas considered an unjust law a ‘crooked law’, and, as such, nobody would have to obey it. For St Aquinas, since God’s justice was the basic foundation for the rule-of-law system, a ‘law’ that prescribed murder or perjury was not really law, for people would have the moral right to disobey unjust commands. Rulers who enact unjust ‘law’ cease to be authorities in the rightful sense, becoming mere tyrants. The word ‘tyranny’ comes from the Greek for ‘secular rule’, which means rule by men instead of the rule of law.

In declaring the equality of all human souls in the sight of God, Christianity compelled the kings of England to recognize the supremacy of the divine law over their arbitrary will. ‘The absolutist monarch inherited from Roman law was thereby counteracted and transformed into a monarch explicitly under law.’5 The Christian religion worked there as a civilizing force and a stranger to despotism. As one may say, ‘The Bible’s message elevated the blood-drinking “barbarians” of the British Isles to decency.’6

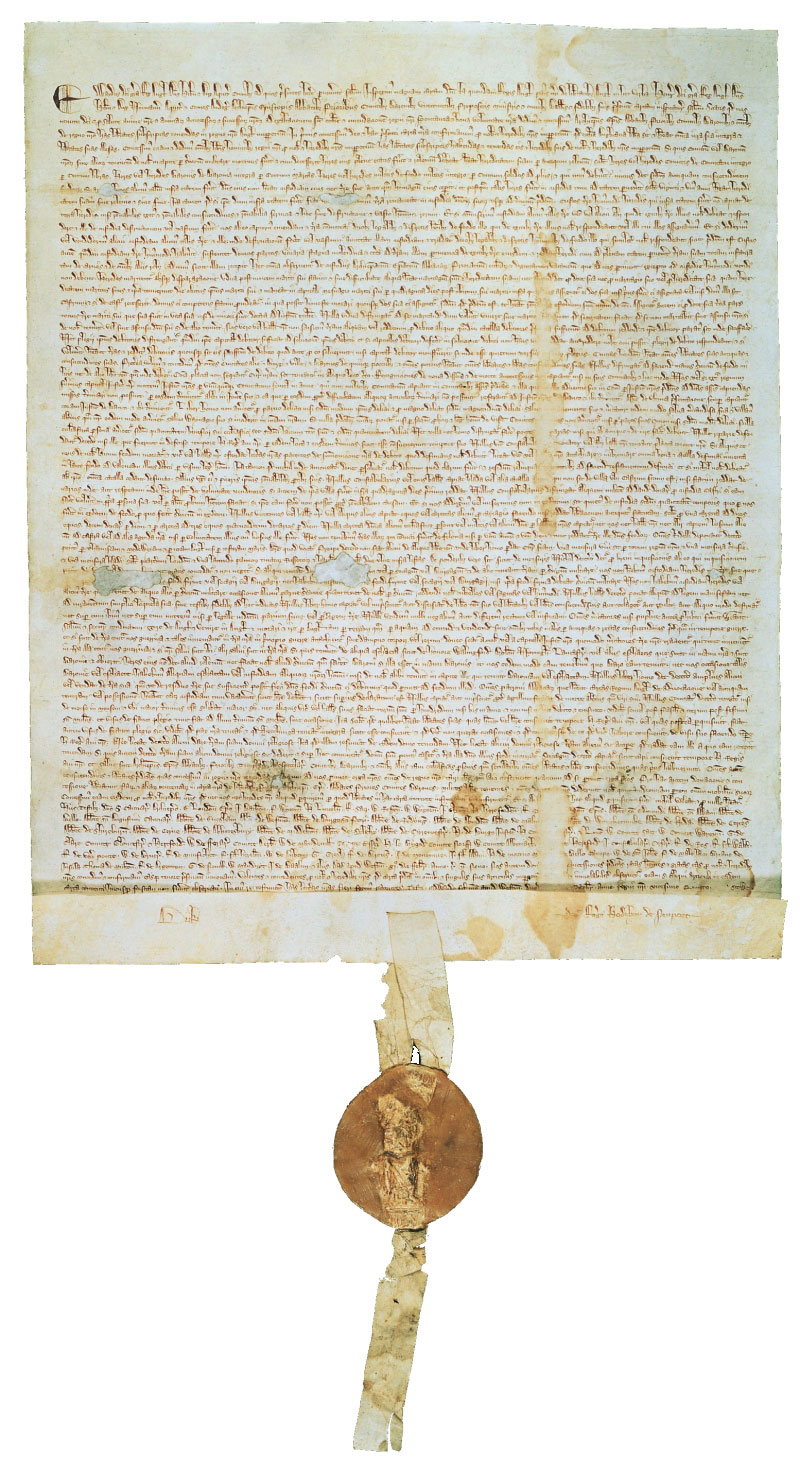

At the time of Magna Carta (1215), a royal judge called Henry de Bracton (d. 1268) wrote a massive treatise on principles of law and justice. Bracton is broadly regarded as ‘the father of the common law’, because his book De legibus et consuetudinibus Anglia is one of the most important works on the constitution of medieval England. For Bracton, the application of law implies ‘a just sanction ordering virtue and prohibiting its opposite’, which means that the state law can never depart from God’s higher laws. As Bracton explains, jurisprudence was ‘the science of the just and unjust’.7 And he also declared that the state is under God and the law, ‘because the law makes the king. For there is no king where will rules rather then the law.’8

The Christian faith provided to the people of England a status libertatis (state of liberty) which rested on the Christian presumption that God’s law always works for the good of society. With their conversion to Christianity, the kings of England would no longer possess an arbitrary power over the life and property of individuals, changing the basic laws of the kingdom at pleasure. Rather, they were told about God’s promise in the book Isaiah, to deal with civil authorities who enact unjust laws (Isaiah 10:1). In fact, the Bible contains many passages condemning the perversion of justice by them (Prov 17:15, 24:23; Exo 23:7; Deut 16:18; Hab 1:4; Isa 60:14; Lam 3:34). In explaining why the citizens of England had much more freedom than their French counterparts, Charles Spurgeon (1834–1892) declared:

‘There is not land beneath the sun where there is an open Bible and a preached gospel, where a tyrant long can hold his place … Let the Bible be opened to be read by all men, and no tyrant can long rule in peace. England owes her freedom to the Bible; and France will never possess liberty, lasting and well-established, till she comes to reverence the Gospel, which too long has rejected … The religion of Jesus makes men think, and to make men think is always dangerous to a despot’s power.’9

Reasons for a civil government

The first reference to civil government in the Holy Scriptures is found in chapter 9 of the book of Genesis. In this chapter, God commands capital punishment for those who take the life of human beings, who are always created in the image of God. In this sense, the right to execute murderers does not belong to government officials themselves, but to God who is the author of life and commands the death penalty for murder in several passages of the Holy Scriptures (e.g. Exod 21:12; Num 35:33). Thus, life can only be taken away from the individual if civil authorities apply it under God’s law and commission, as the sanctity of human life is the basis on which God sanctions capital punishment. As John Stott explains:

‘Capital punishment, according to the Bible, far from cheapening human life by requiring the murderer’s death, demonstrates its unique value by demanding an exact equivalent to the death of the victim.’10

The state is a ‘necessary evil’ that has to be subject to God’s higher laws. After sin entered in the world, it became necessary to establish the civil government in order to curb violence (Gen 6:11–13). However, the state was not envisaged in God’s original plan for mankind, as it places some people in a position of authority over others. At the beginning of the creation, however, Genesis tells us that man and woman lived in close fellowship with God, under His direct and sole authority.11 Then Thomas Paine (1737–1809), a non-Christian himself, expressed the biblical worldview when he uttered these words:

‘Government even in its best state is but a necessary evil; in its worst state an intolerable one; for when we suffer, or are exposed to the same miseries by a government, which we might expect in a country without government, our calamities are heightened by reflecting that we furnish the means by which we suffer. Government, like dress, is the badge of lost innocence; the palaces of kings are built on the ruins of the bowers of paradise.’12

The understanding of civil government as a result of our sinful condition justifies the doctrine of limitation of the state powers. It inspired, in both Britain and America, the establishment of a constitutional order based on checks and balances between the branches of government—namely legislative, executive and judicial. Such division obeys the biblical revelation of God as our supreme Judge, Lawgiver and King (Isa 33:22). Since all human beings are born of a sinful nature, the functions of the state ought to be legally checked, because no human being can be trusted with too much power.

Because God instilled in each of us a desire for freedom, political tyranny, as Lord Fortescue (1394–1479) explained, is the attempt on the part of civil authorities to replace natural freedom by a condition of servitude that only satisfies the ‘vicious purposes’ of wicked rulers. As Fortescue put it, the law of England provided freedom to the people only because it was fully indebted to the Holy Scriptures. Thus, he quoted from Mark 2:27 to proclaim that the kings are called to govern for the sake of the kingdom, not the opposite. In this sense, he also remarked:

‘A law is necessarily adjudged cruel if it increases servitude and diminishes freedom, for which human nature always craves. For servitude was introduced by men for vicious purposes. But freedom was instilled into human nature by God. Hence freedom taken away from men always desires to return, as is always the case when natural liberty is denied. So he who does not favour liberty is to be deemed impious and cruel.’13

By placing God’s higher laws above human law, Sir Edward Coke (1552–1634) considered that the basic laws of England were not designed by the state, but ‘written with the finger of God in the human heart’.14 Coke described the constitution of England as a ‘harmonious system’ sustained primarily by God’s higher laws. Then he went on to declare that no statute enacted by the Parliament is valid if it does not respect God and the law. Finally, Lord Coke wisely pointed out:

‘In nature, we see the infinite distinction of things proceed from some unity, as many rivers from one fountain, many arteries in the body of man from one heart, many veins from one liver, and many sinews from the brain: so without question this admirable unity and consent in such diversity of things proceeds only from God, the fountain and founder of all good laws and constitutions.’15

How the idea of ‘evolution’ undermines the rule of law

The notion that human law is always subject to God’s higher laws started to be more deeply challenged in the nineteenth century. After the work of Charles Darwin, belief in evolution presupposed the non-existence of God’s natural moral order as a primary source of positive law. Thus, legal positivists decided to regard the positive law of the state as a mere result of sheer force and social struggle. In brief, a product of human will.

But if laws are caught up in the faith of ‘evolution’, laws can no longer be regarded as possessing a transcendental dignity. Then the very idea of government under law loses its philosophical foundations, and, as a result, societies start to lack a moral condition of legal culture that allows them to effectively restrain the emergence of an all-powerful state.16 As J.R. Rushdoony pointed out:

‘When man is made controller of his own evolution by means of the state, the state is made into the new absolute. Hegel, in accepting social evolution, made the state the new god of being. The followers of Hegel in absolutizing the state are Marxists, Fabians, and other socialists … In brief, God and His transcendental law are dropped in favor of a new god, the state. Evolution thus leads not only to revolution but also to totalitarianism. Social evolutionary theory, as it came to focus in Hegel, has made the state the new god of being. Biological evolutionary thinking, as it has developed since Darwin, has made revolution the great instrument of this new god and the means to establishment of this new god, the scientific socialist state.’17

Behind every legal order there is always a god, be it God Himself or those who have control over the state machinery.17 The state becomes a ‘god’ in itself if there is no ultimate appeal to higher laws and authority. Whenever the law of the state is regarded as the only source of legality, civil rulers become all-powerful authorities over the life and liberties of the individual. For no legal protection can be reasonably afforded against tyranny, if the supremacy of God’s higher laws is not made to prevail. In this way, Douglas W. Kmiec, a law professor at the University of Notre Dame, has correctly remarked:

‘Views and opinions antagonistic to God’s plan, whether fashioned in legislative enactment or “spontaneously” over an extended period of time in judicial decree, are hardly immutable first principles and they have led, and continue to lead, to the defeat of our happiness.’18

The complexity of things that are held together in the universe indicates the existence of a Supreme Lawmaker. As we see the world as it really is, we must concede that its motions are directed by invariable and fixed rules of law. If there are laws sustaining the world, then who has created these laws? In this regard, as Montesquieu commented:

‘Those who assert that a blind fatality might have produced the various effects we behold in this world are guilty of a very great absurdity; for can anything be more absurd than to pretend that a blind fatality could be productive of intelligent beings?

‘God is related to the universe as Creator and Preserver. The laws by which He has created all things are those by which He preserves them. He acts according to these rulers because He knows them; He knows them because He has made them; and He made them because they are relative to His wisdom and power.

‘Particular intelligent beings may have laws of their own making, but they also have some which they never made … To say that there is nothing just or unjust but what is commanded or forbidden by positive [human] laws is the same as saying that before the describing of a circle all the radii were not equal.

‘We must therefore acknowledge the existence of relations of justice antecedent to positive law, and by which they are established … If there are intelligent beings that have received a benefit of another being, they ought to be grateful; if one intelligent being has created another intelligent being, the latter ought to continue in its original state of dependence.

‘But the intelligent world is far from being so well governed as the physical one. For though the former has also its laws which of their own nature are invariable, yet it does not conform to them so exactly as the physical world. This is because on the one hand intelligent human beings are of finite nature and consequently liable to error; and, on the other, their nature requires them to be free agents. Hence they do not steadily conform to their primitive laws; and even those of their own instituting they frequently infringe.

‘Man, as a physical being, is, like other bodies, governed by invariable laws. As an intelligent being, he incessantly transgresses these laws established by God and changes even the ones which he himself has established. Then, he is left to his own direction, though he is a limited being and subject like all finite intelligences to ignorance and error. And even the imperfect knowledge he has, he loses it as a sensible creature when it is hurried away by a thousand impetuous passions. Such a being might every instant forget his Creator. For this reason, God has reminded him of his obligations by the law of [the Judaeo-Christian] religion.’19

God’s Law is above the state law

The human intellect should not be our basic reference in terms of legality because everyone is affected by a sinful nature. Then, our basic legal rights should be considered the ones revealed by God Himself through the Holy Scriptures. According to the doctrine of natura delecta, which means that our human nature has been damaged by the original sin, law is not so much to be based on human wisdom as on God’s wisdom and sovereign will. As the Bible says, ‘The foolishness of God is wiser than man’s wisdom, and the weakness of God is stronger than man’s strength’(1 Cor 1:25).

The rule of law can only subsist if civil authorities are able to respect the hierarchical prevalence of God’s higher laws over the state law. Although the law of God is always perfect, for God’s wisdom is always perfect, human authorities are sinful creatures who might have their minds controlled by desires of the flesh. They may be slaves of sin and rebels against God, although citizens who elect sinful people and obey their wicked rulings are slaves of sin as well.

A basic question of the rule of law is to know which sort of authority we want as the ultimate source of power over ourselves: the authority of a loving God or the authority of a sinful human ruler. If we decide for the sinful ruler, then, as R.J. Rushdoony puts it, ‘we have no right to complain against the rise of totalitarianism, the rise of tyranny—we have asked for it’.20

To avoid tyranny, William Blackstone (1723–1780) once declared that no human law could be valid if it contradicted God’s higher laws which maintain and regulate natural human rights to life, liberty, and property.21 According to Blackstone’s biblical understanding of the rule of law,

‘No human laws should be suffered to contradict [God’s] laws … Nay, if any human law should allow or enjoin us to commit it, we are bound to transgress that human law, or else we must offend both the natural and the divine.’ 22

The biblical understanding of lawful resistance against tyranny

When God delegates His supreme authority to human rulers, they have no liberty to use it in order to justify tyranny. In fact, there are quite remarkable examples in the Holy Scriptures where God explicitly commands civil disobedience against the state. For example, Egyptian midwives refused to obey the Pharaoh’s order to kill Hebrew babies. As the Bible says, ‘[they] feared God and did not do what the king of Egypt told them to do’ (Exod 1:17). Likewise, three Hebrews did not obey Babylon’s King Nebuchadnezzar, when he commanded everyone to bow down and worship his golden image (Dan 6). Daniel also refused to obey a decree enacted by King Darius, which forced everyone not to pray to any god or men except to himself.

In the New Testament, we have the example of the first Apostles’ attitude towards the Sanhedrin, a Jewish council of priests and teachers of the law. The council ordered them not to preach in the name of Christ Jesus. However, the Book of Acts says that the Apostles refused to obey their decision, and, as the Apostle Peter boldly declared, ‘We must obey God rather than human authority’ (Acts 5:29, NLT). In fact, the zeal of the Apostles for the Lord was so great that they refused to be silenced by unfair rulers, even if such a refusal resulted in arrest and/or execution. They considered themselves bound by God’s Law in the first place, and kept on preaching the Gospel as if it were no legal prohibition. To be obeyed, therefore, civil authorities have firstly to obey God and the law. As John Stott has pointed out:

‘If the state commands what God forbids, or forbids what God commands, then our plain Christian duty is to resist, not to submit, to disobey the state in order to obey God … Whenever laws are enacted which contradict God’s law, civil disobedience becomes a Christian duty.’23

Although the first Apostles regarded it as totally lawful to disobey ungodly legislation, today’s followers of Christ like to quote from chapter 13 of Paul’s letter to the Romans in order to justify their compliance with immoral rules of positive law. However, Paul argues here that we obey the civil authority because it holds ‘no terror for those who do right, but for those who do wrong’ (Rom 13:3 NIV). If the person who holds the state power abuses his or her God-given power, ‘our duty is not to submit, but to resist’.24 According to F.A. Schaeffer, a more accurate interpretation of this passage would clearly indicate that ‘the state is to be an agent of justice, to restrain evil by punishing the wrongdoer, and to protect the good in society. When it does the reverse, it has not proper authority. It is then a usurped authority and as such it becomes lawless and is tyranny.’25

God has established the state as delegated authority, not an autonomous power above the law. When we obey the state it is not that we obey individuals who are in charge of the state machinery, but it is rather for obedience to a God-given authority who is commanded by God to promote natural principles of liberty and justice. Therefore, as Pope John XXIII explains in his encyclical ‘Pacem in Terris’:

‘Since the right to command is required by the moral order and has its source in God, it follows that, if civil authorities pass laws or command anything opposed to the moral order and consequently contrary to the will of God, neither the laws made nor the authorizations granted can be binding on the consciences of the citizens, since God has more right to be obeyed than men. Otherwise, authority breaks down completely and results in shameful abuse.’26

Because Paul also says that the Word of God is not to be bound (2 Tim 2:9 NIV), the right of resistance against tyranny is an important element of the rule-of-law system ordained by Him. For this reason, as John Knox (1513–1572) put it, to rebel against a wicked ruler can be the same as to oppose the devil himself, ‘who is the one abusing from the sword and authority of God’.27 Knox stated that anyone who dares to rule over a nation against the law of God can be lawfully resisted, even by force if necessary.28 According to John Knox, if the civil ruler seems to be effectively willing to destroy the Christian foundations of the society,

‘[God] hath commanded no obedience, but rather He hath approved, yea, and greatly rewarded, all those who have opposed themselves to their ungodly commandments and blind rage.’29

Samuel Rutherford (1600–1661), a Scot Presbyterian like John Knox, developed in ‘Lex Rex’ a consistent doctrine of lawful resistance against political tyranny. According to Rutherford, if people wish to effectively stay free from such tyranny, then they will have to preserve their inalienable right to eventually disobey unjust legislation. For him, ‘A power ethical, politic, or moral, to oppress, is not from God, and is not a [lawful] power, but a licentious deviation of a [lawful] power.’30 And in answer to the royalists who liked to use Romans 13 in order to condemn any form of resistance against the government, as a resistance against God Himself, Rutherford boldly proclaimed:

Image courtesy library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

‘It is a blasphemy to think or say that when a king is drinking the blood of innocents and wasting the Church of God, that God, if he were personally present, would commit these same acts of tyranny.’31

John Locke (1634–1704), whose legal and political ideas provided legal justification to the 1688 ‘Glorious Revolution’ in Britain, argued that lawmakers put themselves into a ‘state of war’ against the society whenever they endeavour to destroy our God-given ‘natural’ rights to life, liberty and property. For Locke, no government has the right to reduce these basic rights of the individual citizen. If so, Locke argued that people would be left ‘at the common refuge that God has provided for all men against force and violence’.32

The American Founding Fathers fully acknowledged the principle of lawful resistance against tyranny, and drew heavily from this in order to justify their revolutionary actions against the British government, in 1776. Written by Thomas Jefferson, the US Declaration of Independence argues that revolution is the last recourse of a free people against ‘a long train of abuses and usurpations’ on the part of the government. Thus, they justified their actions on the grounds that God has endowed each human being with natural rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, which are basic rights that not even the state can take away from them.

Of course, any revolutionary uprising, as Pope Paul VI comments in his encyclical ‘Popularum Progressio’, can only be justified in extraordinary situations ‘where there is a manifest, long-standing tyranny which would do great damage to fundamental personal rights and dangerous harm to the common good of the country’.33 However, the recourse to violence, as a means to right the wrongs of the state against the rule of law, risks itself to produce new forms of injustice. Therefore, Pope Paul VI also stated that revolutionary uprising can only be carried out as the last remedy against long-standing tyranny, because, as he put it, ‘a real evil should not be fought against at the cost of greater misery’.33

The rule of law, Christianity and human rights

According to the Judeo-Christian worldview, human beings were created by God and, as such, have never ‘acquired’ their basic rights from the state. Nor are such basic rights a result of any work performed by them, but it flows directly from the nature of each human being who is always conceived in the image of a loving God (Gen 1:26).

According to Genesis 1:27–28, God created all human beings, male and female, in His own image, commanding them to fill the earth and subdue it. We found here a very special meaning for the recognition of human dignity, as the result of the relationship between God and His human creatures, which the Fall has distorted but not destroyed. From this fact it follows, for instance, that widows will not be burned on their husband’s funeral pyre, as they still are in India, and that people will not be sold to slavery, as they still are in Sudan.34

Every year, Freedom House, a secular organization, conducts a survey to analyze the situation of democracy and human rights across the globe. Year after year, it concludes that the most rights-based and democratic nations are the majority-Protestant ones. On the other hand, Islam and Marxism, the latter a secular religion, seem to offer the most serious obstacles for the realization of democracy and human rights. In fact, the denial of the broadest range of basic human rights comes precisely from Marxist and majority-Muslim countries. The worst violators of human rights are Libya, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Syria, Turkmenistan, and the one-party Marxist regimes of Cuba and North Korea.35

In contrast to Islam, Christianity has democratized political manners, and still is the main moral force that holds democratic values together in the West. It provides the strongest argument for the protection of basic human rights. For Paul L. Maier, Professor of Ancient History at Western Michigan University, ‘no other religion, philosophy, teaching, nation, movement—whatever—has so changed the world for the better as Christianity has done’.36

In declaring that we all stand on equal ground before God, Christianity gives the best moral foundations for social and political equality.34 If Christianity is found to be true, the individual, male or female, is not only more important but incomparably more important than the social body. This helps to explain, in Charles Colson’s opinion, ‘why Christianity has always provided not only a vigorous defence of human rights but also the sturdiest bulwark against tyranny’.34

Conclusion

A visible fact in these days of moral relativism is the gradual abandonment of the Christian faith and culture in the Western world. As a result, the moral foundations for the rule of law have been seriously undermined. Westerners who believe that abandonment of Christianity will serve for democracy and the rule of law are blindly ignoring that such abandonment has already brought totalitarianism and mass-murder to several Western countries, particularly to Germany and Russia. Any honest analysis of contemporary Western history would have to recognize that no effective legal protection against tyranny can, in the long run, be sustained without the higher standards of justice and morality brought into the texture of Western societies by Christianity.

Westerners who disparage their Christian heritage should get much better informed that were it not for this religion, they would not have the freedoms they enjoy today, for instance, to dishonour the very source of these freedoms, namely Christianity.37 Regarding the present climate of multiculturalism, it would be better for them to think much more carefully on the words uttered by a great historian, Carlton Hayes:

‘Wherever Christians’ ideals have been generally accepted and their practice sincerely attempted, there is a dynamic liberty; and wherever Christianity had been ignored or rejected, persecuted or chained to the state, there is tyranny.’38

Re-posted on homepage: 15 October 2013

References and notes

- Frothingham, R., The Rise of the Republic of the United States, Brown, Boston, MA, p. 6, 1910. Return to text.

- Constant, B., De La Liberté Des Anciens Comparée à celle des Modernes; from: ‘Écrits Politiques’, Folio, Paris, pp. 591–619, 1997. Return to text.

- Fustel De Coulanges, N.D., The Ancient City : A Classic Study of the Religious and Civil Institutions of Ancient Greece and Rome, Doubleday Anchor, New York, p. 223, 1955. Return to text.

- St Augustine; The City of God, Book III, par. 28, Cambridge University Press, Cambrdge, UK, 1998. Return to text.

- Tamanaha, B.Z., On The Rule of Law: History, Politics, Theory, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, p. 23, 2004. Return to text.

- Batten, D. (Ed.), The Creation Answers Book, Creation Ministries International, Brisbane, p. 7, 1999. Return to text.

- Bracton, H., On the Laws and Customs of England, Vol. II, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, p. 25, 1968. Return to text.

- Bracton, ref. 7, p. 33. Return to text.

- Spurgeon, C.H., Joy Born at Bethlehem; in: Water, M. (Ed.), Multi New Testament Commentary, John Hunt, London, p. 195, 1871. Return to text.

- Stott, J., Christian Basics: An Invitation to Discipleship, Monarch Books, London, p. 79, 2003. Return to text.

- Adamthwaite, M., Civil Government, Salt Shakers 9:3, June 2003. Return to text.

- Paine, T., Of the origin and design of government; in: Boaz, D. (Ed.), The Libertarian Reader: Classic and Contemporary Writings from Lao-Tzu to Milton Friedman, Free Press, New York, p. 7, 1997. Return to text.

- Fortescue, Sir J., De Laudibus Legum Anglie, translated with Introduction by Chrimes, S.B., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, Chapter XLII, p. 105, 1949. Return to text.

- 7 Co. Rep. I, 77 Eng. Rep. 277 (K.B. 1960). Apud: Wu, John C.H.; Fountain of Justice: A Study in the Natural Law, Sheed and Ward, New York, p. 91, 1955.Return to text.

- Coke, Sir E., Third Reports, 3. Apud: Sandoz; Elliz; The Roots of Liberty—Introduction; in: The Roots of Liberty: Magna Carta, Ancient Constitution, and Anglo-American Tradition of the Rule of Law, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, MO, p. 137, 1993. Return to text.

- See Noebel, D., The Battle for Truth, Harvest House Publishers, Eugene, OR, p. 232, 2001. Return to text.

- Rushdoony, R.J., Law and Liberty, Ross House Books, Vallecito, CA, p. 33, 1984. Return to text.

- Kmiec, D.W., Liberty misconceived: Hayek’s incomplete theory of the relationship between natural and customary law; in: Ratnapala, S. and Moens, G.A. (Eds.), Jurisprudence of Liberty, Butterworths, Adelaide, SA, Australia, p. 145, 1996. Return to text.

- De Montesquieu, C., The Spirit of Laws, Book I, Chapter 1, 1748. Return to text.

- Rushdoony, ref. 17, p. 35. Return to text.

- Blackstone, W., The Sovereignty of the Law—Selections from Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England, McMillan Publishers, London, pp. 58–59, 1973.Return to text.

- Blackstone, ref. 21, pp. 27–31. Return to text.

- Stott, J., The Message of Romans: God’s Good News for the World, Inter-Varsity Press, London, p. 342, 1994. Return to text.

- Stott, ref. 10, p. 78. Return to text.

- Schaeffer, F.A., A Christian Manifesto, Crossway, Westchester, p. 91, 1988. Return to text.

- Pacem in Terris, Encyclical letter of Pope John XXIII, Paragraph 51, 1963. Return to text.

- Knox, J., On Rebellion, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, p. 192, 1994. Return to text.

- Knox, ref. 27, p. 178. Return to text.

- Knox, ref. 27, p. 95. Return to text.

- Rutherford, S., ‘Lex Rex’, or The Law and the Prince; in: The Presbyterian Armoury, vol. 3, p. 34, 1846. Return to text.

- Rutherford, ref. 30, Arg. 4. Return to text.

- Locke, J., Second Treatise on Civil Government, Sec. 222; From Locke, J., Political Writings, Penguin Books, London, p. 374, 1993. Return to text.

- Popularum Progressio, Encyclical letter of Pope Paul VI, Paragraph 31, 1967. Return to text.

- Colson, C. and Pearcey, N., How Now Shall We Live? Tyndale, Wheaton, IL, p. 131, 1999. Return to text.

- Karatnycky, A., Piano, A. and Puddington, A. (Eds.),Freedom in the World 2003: The Annual Survey of Political Rights and Civil Liberties, Freedom House, New York, pp. 11–12, 2003. Return to text.

- Maier, P.L., foreword to: Schmidt, A.J., How Christianity Changed the World, Zondervan, Grand Rapids, MI, p. 9, 2004. Return to text.

- Schmidt, A.J., How Christianity Changed the World, Zondervan, Grand Rapids, MI, p. 13, 2004. Return to text.

- Hayes, C.J.H., Christianity and Western Civilization, Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA, p. 21, 1954. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.