Darwin’s illegitimate brainchild

If you thought Darwin’s Origin was original, think again!

The concept of evolution by natural selection is sometimes referred to as Charles Darwin’s brainchild, and indeed he often referred to it in his letters to his friends as his dear ‘child’. However, this is a far cry from the facts. At best it was an adopted child; at worst an illegitimate child.

Erasmus Darwin and James Hutton—1794

In the last issue of Creation, we showed that Charles’s humanist grandfather, Erasmus Darwin, preempted Charles on the subject of evolution by some 65 years with his book Zoonomia (1794), and that Charles used almost every topic discussed and example given in this work in his own On the Origin of Species, published in 1859.1

Now new evidence has emerged that a Scottish geologist, Dr James Hutton (1726–1797), conceived a theory of selection as early as 1794. Hutton is best known as the man who proposed that the earth was ‘immeasurably’ old, not thousands of years, because he rejected the Flood of the Bible and so erroneously assumed that there were no major catastrophes in the earth’s early history.2

Paul Pearson, professor of paleoclimatology at Cardiff University, has recently found in the National Library of Scotland a formerly unpublished work of three volumes and 2,138 pages, written by Hutton in 1794. Entitled An Investigation of the Principles of Knowledge and of Progress of Reason, from Sense to Science and Philosophy,3 it contains a full chapter on Hutton’s theory of ‘seminal variation’.4

For example, Hutton said that among dogs that relied on ‘nothing but swiftness of foot and quickness of sight’ for survival, the slower dogs would perish and the swifter would be preserved to continue the race. But if an acute sense of smell was ‘more necessary to the sustenance of the animal’, then ‘the natural tendency of the race, acting upon the same principle of seminal variation, would be to change the qualities of the animal and to produce a race of well scented hounds, instead of those who catch their prey by swiftness’. And he went on to say, ‘The same “principle of variation” must also influence “every species of plant, whether growing in a forest or a meadow”.’5

Others—1831–1858

Apart from James Hutton, there were several other authors who, many years before Charles Darwin, published articles on the subject of natural selection.

William Wells (1757–1817) was a Scottish-American doctor who, in 1813 (and published posthumously in 1818), described a concept like natural selection. He said that in central Africa some inhabitants ‘would be better fitted than the others to bear the diseases of the country. This race would consequently multiply, while the others would decrease.’ He went on to say that ‘the color of this vigorous race … would be dark’ and that ‘as the darkest would be the best fitted for the climate, this would at length become the most prevalent, if not the only race, in the particular country in which it had originated’.6

Patrick Matthew (1790–1874) was a Scottish fruit-grower who, in 1831, published a book On Naval Timber and Arboriculture, in the appendix of which he briefly mentioned natural selection and evolutionary change. Matthew publicly claimed that he had anticipated Charles Darwin, and even described himself on the title pages of his books as ‘Discoverer of the Principle of Natural Selection’.

Professor Pearson points out that Wells, Matthew and Charles Darwin were all educated in the university city of Edinburgh, ‘a place famous for its scientific clubs and societies’, which was also Hutton’s home town. He makes the interesting suggestion ‘that a half-forgotten concept from his [Charles’s] student days resurfaced afresh in his mind as he struggled to explain the observations of species and varieties compiled on the voyage of the Beagle’.3

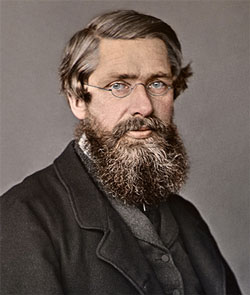

Edward Blyth (1810–1873) was the man whose ideas probably influenced Darwin most. An English chemist and zoologist, Blyth wrote three major articles on natural selection that were published in The Magazine of Natural History from 1835 to 1837.7 Charles was well aware of these. Not only was this one of the leading zoological journals of that time, in which his friends Henslow, Jenyns and Lyell had all published articles, but also it seems that the University of Cambridge, England, has Darwin’s own copies of the issues containing the Blyth articles, with Charles’s handwritten notes in the margins!8

Charles Darwin’s ‘Historical Sketch’

After the publication of his Origin of Species in 1859, Charles was accused by his contemporaries of failing to acknowledge his debt to these and other predecessors who had written about natural selection. The cry became so loud that, in 1861, he found it necessary to add a Historical Sketch, which listed some of these previous writers, to the third edition of his Origin. Then, under continued attack, he enlarged this in three subsequent editions until, in the 6th and last edition, he mentioned some 34 other authors who had previously written on how species originated or changed. But he gave very few details of what they had said, and they were sealed off in the Historical Sketch, away from the main line of discussion. Darlington calls it ‘the most unreliable account that ever will be written’.9

This was not enough for the English satirist Samuel Butler. In 1879, he wrote Evolution Old and New, a book in which he accused Darwin of slighting the evolutionary speculations of Buffon, Lamarck and Darwin’s own grandfather, Erasmus.

Modern accusations of plagiarism

One of the leading modern evolutionists to claim that Darwin ‘borrowed’ (some would say ‘plagiarized’) the works of others was the late Loren Eiseley, who was Benjamin Franklin Professor of Anthropology and the History of Science at the University of Pennsylvania before his death.

Eiseley spent decades tracing the origins of the ideas attributed to Darwin. In a 1979 book,10 he claimed that ‘the leading tenets of Darwin’s work—the struggle for existence, variation, natural selection and sexual selection—are all fully expressed in Blyth’s paper of 1835’.11 He also cites ‘Blythisms’ and use of rare words by Darwin (such as ‘inosculate’, meaning to pass into), after it appeared in Blyth’s paper of 1836, similarities of phrasing, and Darwin’s choice of similar lists of creatures in similar contexts.12

Eiseley’s work seems to have encouraged other 20th-century evolutionists to speak up. Darlington accused Darwin of ‘a flexible strategy which is not to be reconciled with even average intellectual integrity’.13 In 1981, Hoyle and Wickramasinghe referred to Eiseley’s ‘courageous’ stand and wrote: ‘Darwin by his own account was a voracious reader of other men’s work … . It was not in his character, however, to make a return for what he received.’ And: ‘The evidence does not permit of any conclusion except that the omissions [by Darwin] were deliberate … a serious sin of omission remains to be redeemed by the world of professional biology.’14

It is true that in his Origin, Charles mentions correspondence with, or information from, Blyth—on the habits of Indian cattle, the hemionus [Asian wild ass] and crossbred geese,15 but, as Eiseley comments: ‘Blyth is restricted to the role of taxonomist and field observer.’16 So why was Darwin so loath to credit Blyth with the key element of his theory? Why did he not cite Blyth’s papers that dealt directly with natural selection?

Answer: Probably for two reasons.

Blyth was a Christian and what we would nowadays call a ‘special creationist’. E.g. concerning the seasonal changes in animal colouring (such as the mountain hare becoming white in winter), Blyth said that these were ‘striking instances of design, which so clearly and forcibly attest the existence of an omniscient great First Cause’.17 And he said that animals ‘evince superhuman wisdom, because it is innate, and therefore, instilled by an all-wise Creator’.18

Blyth correctly saw the concept of natural selection as a mechanism by which the sick, old and unfit were removed from a population; that is, as a preserving factor and for the maintenance of the status quo—the created kind.19 Creationists like Edward Blyth (and English theologian William Paley) saw natural selection as a process of culling; that is, of choosing between several traits, all of which must first be in existence before they can be selected.

Conclusion

History has bestowed the dubious credit for the idea of evolution by natural selection on Charles Darwin. Apart from the fact that selection itself, while a real phenomenon, is utterly impotent to provide the extra information necessary to produce new traits, most, if not all, of the major ideas attributed to Darwin had previously been discussed in print by others. Not only was this ‘brainchild’ of Darwin’s not really his, but it also had many fathers!

Fairness or fear?

Alfred Russel Wallace (1823–1913), while living at Ternate in the Malay Archipelago, independently developed a theory of evolution almost identical with that of Charles Darwin.1

In 1858 he sent Darwin a copy of his manuscript on natural selection, entitled On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart Indefinitely From the Original Type, which outlined in complete form what is now known as the Darwinian theory of evolution.2 Darwin’s friends, Charles Lyell and Joseph Hooker, immediately arranged to have Wallace’s manuscript, along with two earlier unpublished items by Charles Darwin (an 1844 essay and an 1857 letter to Asa Gray), read at the next meeting of the Linnean Society of London, on 1 July 1858.

This has euphemistically been referred to as the reading of a ‘joint paper’, but it all took place without the personal participation of Wallace, and even without his knowledge or permission—he was still on an island off the coast of New Guinea! It also caused Charles to rush through the writing of his Origin of Species, and publish it on 24 November 1859. Some have seen this so-called ‘joint paper’ not as fair play on Darwin’s part, but rather as the result of his fear of being scooped by Wallace.

Brackman says: ‘Wallace, not Darwin, first wrote out the complete theory of the origin and divergence of species by natural selection … and was robbed in 1858 of his priority in the proclaiming of the theory’ (emphasis in the original).3

References and notes

- Wallace had been thinking on the subject as early as 1845, and had published a rather general paper on it in the Annals and Magazine of Natural History, September 1855. See ref. 2, p. 78.

- Eiseley says, ‘It was Darwin’s unpublished conception down to the last detail, independently duplicated by a man sitting in a hut at the world’s end.’ Eiseley, L., Alfred Russel Wallace, SciAm 200(2):80, February 1959.

- Brackman, A., A Delicate Arrangement: The Strange Case of Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace, Times Books, New York, p. xi, 1980.

References and notes

- Grigg, R., Darwinism: it was all in the family, Creation 26(1):16–18, 2003. Return to text.

- Hutton’s views have been summarized as ‘the present is the key to the past’. Hutton’s misconception is now sometimes referred to as uniformitarianism. Return to text.

- Reviewed by Paul Pearson in Nature 425(6959):665, 16 October 2003. Return to text.

- Pearson says that Hutton ‘used the selection mechanism to explain the origin of varieties in nature’, although ‘he specifically rejected the idea of evolution between species as a “romantic fantasy”’. Return to text.

- Quoted from ref. 3. Return to text.

- Quoted by Stephen Jay Gould in Gould, S., Natural selection as a creative force, The Structure of Evolutionary Theory, Belknap Press of Harvard University, Massachusetts, USA, p. 138, 2002. Return to text.

- Blyth, E., The Magazine of Natural History Volumes 8, 9 and 10, 1835–1837. Sourced from ref. 8, Appendices. Return to text.

- Source: Bradbury, A., Charles Darwin—The truth? Part 7—The missing link, www3.mistral.co.uk, 30 October 2003. Return to text.

- Darlington, C.D., The origin of Darwinism, Scientific American 200(5):61, May 1959. Return to text.

- Eiseley, L., Darwin and the Mysterious Mr X, E.P. Dutton, New York, 1979, published posthumously by the executors of his will; from Eiseley, L., Charles Darwin, Edward Blyth, and the Theory of Natural selection, Proc. Am. Philos. Soc. 103(1):94–114, February 1959. Return to text.

- Ref. 10, p. 55. Return to text.

- Ref. 10, pp. 59–62. Return to text.

- Darlington, C.D., Darwin’s Place in History, Basil Blackwell, Oxford, p. 60, 1959. Return to text.

- Hoyle, F. and Wickramasinghe, C., Evolution from Space, Paladin, London, pp. 175–179, 1981. Return to text.

- Darwin, C., The Origin of Species, 6th ed., John Murray, London, pp. 21, 199, and 374 respectively, 1902. Return to text.

- Ref. 10, p. 52. Return to text.

- Blyth, E. (1835), ref. 7. Return to text.

- Blyth, E. (1837), ref. 7. Return to text.

- Wieland, C., Muddy waters: Clarifying the confusion about natural selection, Creation 23(3):26–29, 2001. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.