Canyon creation

Faster than most people would think possible, beauty was born from devastation

Georgia’s ‘Little Grand Canyon’

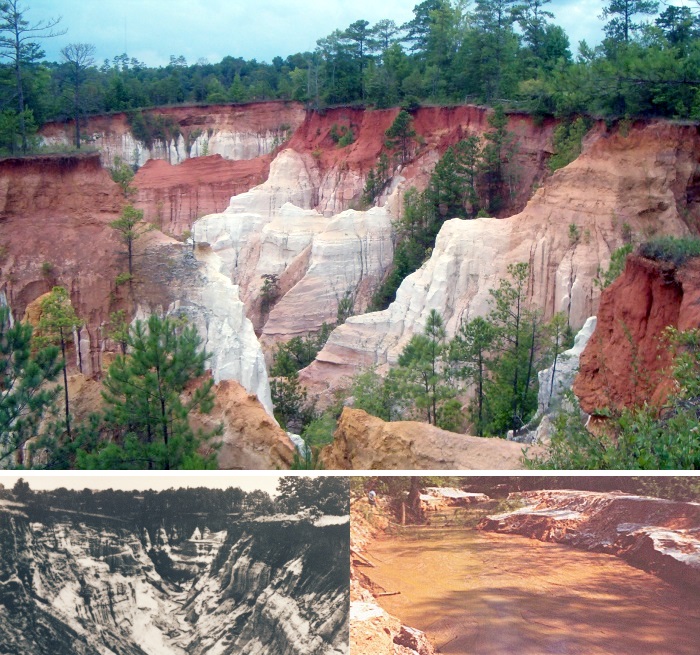

View (top) looking into a part of the canyon shows it disappearing deeply below the cover of trees. An old photograph (above, left) shows the canyon before foliage had taken root. The small stream running through the base represents only a tiny portion of the water which during storms has ravaged the sediment, stripping it away to leave this colossal hole in the ground. What began as tiny furrows in the ground due to poor farming and land practices has resulted in a landscape that is mute testimony to the power of water over a short time period. Downstream (above, right), the river reveals large amounts of sediment which has run off as drainage from the canyon area. Had the history of this site not been known it seems very likely that a much older age would have been assigned to it.

Many people believe canyons take a long time to form. In North America, though, there is a canyon that simply wasn’t there 150 years ago.1

Providence Canyon is near the town of Lumpkin in southwest Georgia. Where there were once rolling hills covered with untouched pine forest, there is now a deep chasm with nine finger-like canyons. They range in size up to 50 m (160 ft ) deep, 180 m (600 ft) wide and 400 m (1,300 ft) long.2,3

The exposed canyon bluffs are extremely beautiful with many bands of different coloured rocks—bright red clay, white kaolin, as well as sands coloured ochre, pink, orange, beige, purple, lavender, grey, yellow, tan and black.4,5

In the base of the canyon, where it is often humid, trees such as sweet gums, weeping willows, tupelo, maples and blackjack oaks grow.2

The area is a haven for over 150 varieties of wildflowers, including dwarf irises, rhododendrons, foxgloves, magnolias, evening primroses and the rare red and orange plumleaf azaleas.6,7,8

Wildlife such as white-tailed deer, red and grey foxes, raccoons, armadillos and birds such as woodpeckers, warblers, turkeys, thrushes and owls may be seen.8

What happened here?

What caused this dramatic change from rolling hills to such a ruggedly beautiful landscape? It’s all tied up with the settlement of the area for farming in the early 1800s.

Native Americans of the Creek (Muscogee)9 tribe inhabited the area now known as Georgia long before European settlement. Between 1790 and 1830, as the European population increased six-fold, Creek land was successively resumed by the state government for settlement by farmers.10

Local folklore says that trickles of water running down old Native American trails started the erosion.11 Other stories say that water running off a barn built by the Patterson family in 18553 or perhaps off the local schoolhouse roof,4,11 caused the problem. These accounts aren’t too far from the truth.

Bad farming practices

From the 1820s onward, clear-felling of trees (the roots of which deeply stabilize soil), to grow crops such as cotton and corn, set the scene for the start of rampant erosion,3,5 as the land was exposed to the ravages of water run-off during the area’s frequent heavy thunderstorms.12

The uppermost strata comprised the resistant iron-rich clay of the Clayton formation, and overlay the less resistant unconsolidated sands of the Providence and Ripley formations.13 Erosion accelerated once the water got beneath the red clay to the sands underneath.12

Back then, farmers did not preserve topsoil, or use fertilizers.3,14 Their habit was to exhaust the land with crops and then abandon it.15 By ploughing up and down hills, instead of across, they encouraged erosion gullies to form.16

Old people living in Lumpkin in the 1940s say they remember stepping over ditches only 1 to 1.5 m (3 to 5 ft) deep on their way to school in the long-gone township of Humber in this area.17

Growing canyon forced church to move

Historical records show that the local Providence United Methodist church opened in 1832.1 The church had to be moved in 1859 because of the danger of being undermined by the growing canyon.12

Heavy rainfall during storms removed vast amounts of sand and silt from the canyon walls to the floor. These were then washed down the braided Turner’s Creek into the Chattahoochee River.11,12 On the way, the sediment blocked off the end of neighbouring valleys, forming two lakes known as North and South Glory Holes.12

In the 1940s, farmers had to watch every little ditch in case it turned into another gully. They said the soil melted like sugar and ran like water.11

Each year, most farmers lost some animals and farm equipment over the canyon rim. Once anything went over it was abandoned because recovery was extremely difficult.11

Locals spoke of lying in bed on cold winter nights during heavy rain and hearing bangs that sounded like cannon fire, as big chunks of earth fell from the steep-sided walls into the canyons.11

Scientists have studied cores to find out how quickly sediments were deposited in the lakes from debris washed down the creek. After they had correlated the core sediment layers with the heavy rainfall records taken at Lumpkin, they tentatively estimated that canyon development started in 1846.12 It was only 13 years later that the church had to be shifted to the other side of the road because the canyon had come too close!

Formation of a state park

By 1971, 448 ha (1,108 acres)18 in the immediate area were set aside to become the Providence Canyon State Park to preserve and protect this unique area.2 The park is now known as one of the seven natural wonders of Georgia and is often called Georgia’s Little Grand Canyon.18

Visitors are able to walk through nine of the canyons that are part of the day access area, or around the trail that skirts the rim where views into the canyon are spectacular.8

Canyon keeps on growing

Measurements taken between 1984 and 1994 confirm that the canyon is still growing mainly in width.19 Even now fences have to be relocated and roads rerouted because of these changes.20

So, it does not take millions of years for huge canyons to form—it just takes the right conditions. If it had not been seen to happen, hardly anyone would have believed it. Erosion after the global Flood would have been especially rapid through the still soft, freshly laid sediments. In fact, it has been documented in this magazine that erosion overall is happening so fast that the continents cannot be millions of years old or they would have all eroded away.21

Providence Canyon beautifully illustrates how the geology of the earth is consistent with the short timescale of the Bible, provided we understand the conditions properly.

References and notes

- Williams, E.L., Providence Canyon, Stewart County, Georgia—Evidence of recent rapid erosion, CRSQ 32(1):29–43, 1995. Return to text.

- Tanner, C.M., Providence Canyon, Outdoor Photographer magazine, Georgia, USA, March, 1998; outdoorphotographer.com, accessed March 2000. Return to text.

- Ref. 1, pp. 30, 32. Return to text.

- Hunt, B., Providence Canyon State Park, Backpacker magazine, Georgia, USA; bpbasecamp.com, accessed March 2000. Return to text.

- Lack, F., A travel diary of our golden years; tppm.web2010.com, accessed March 2000. Return to text.

- Department of Natural Resources, Parks & Historic Sites, Providence Canyon & Conservation Park; georgiastateparks.org, accessed March 2000. Return to text.

- Ref. 2, p. 2. Return to text.

- Providence Canyon; n2backpacking.com, accessed March 2000. Return to text.

- Muscogee (Creek) history; ocevnet.org, accessed March 2000. Return to text.

- Native Americans in North Georgia, the trail of tears; ngeorgia.com, accessed March 2000. Return to text.

- Severson, H., Canyons while you wait, Ford Times 41(1):19, January 1949. Return to text.

- Hyatt, J.A. and Gilbert, R., Lacustrine sedimentary record of human-induced gully erosion and land-use change at Providence Canyon, Southwest Georgia, USA, J. Paleolimnology 23(4):421–438, 2000. Return to text.

- Ref. 1, p. 32. Return to text.

- Range, W., A Century of Georgia Agriculture, 1850–1950, University of Georgia Press, Athens, Georgia, USA, p. 3, 1954. Return to text.

- Ref. 14, p. 18. Return to text.

- Ref. 14, p. 19. Return to text.

- Ref. 11, p. 17. Return to text.

- Outdoors Online; llbean.com, accessed March 2000. Return to text.

- Ref. 1, p. 36. Return to text.

- Ref. 1, p. 37. Return to text.

- Walker, T., Eroding ages, Creation 22(2):18–21, 2000; creation.com/erosion. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.