Clever crustaceans

This is the pre-publication version which was subsequently revised to appear in Creation 31(2):38–39.

Recently, while fishing at the seashore with my teenage son, I was concerned to see he’d walked out to the edge of a wave-swept slab of rock in an effort to un-snag his line from it.

Knowing of the large numbers of ‘rock fishermen’ washed to their deaths, I gestured him to go back up to the dry part of the rock, beyond the reach of the surging waves.

Later, away from the noise of wind and surf, my son told me of the most amazing thing he’d seen while trying to retrieve his line:

‘You’ll never guess what had snagged my line, Dad—there were two crabs! One was holding my sinker under a rock—stopping me from reeling in my line—while the other crab picked the bait off my hook!’

In my younger days, when I used to believe evolution, I’d have immediately dismissed any possibility of this being evidence that crabs are ‘intelligent’. I would have likely said, ‘Everybody knows crustaceans (and other invertebrates) are way down the evolutionary ladder’, and I would have ruled out any notion of ‘intelligent’ behaviour (let alone cooperation!).

But now, as a Bible-believing Christian, I would be much more cautious about ruling out the possibility of crustacean ‘intelligence’. That’s because the Bible makes it clear there never was any evolutionary progression from ‘primitive and simple’ to ‘advanced and complex’.1

Rather, all kinds of animals were created separately, with man being made in the image of God. With that in mind, it’s not at all surprising that researchers frequently encounter evidence that does not fit the evolutionists’ expectation that apes, as ‘our closest evolutionary relatives’, would be the animals to most closely match the intelligence of humans. See, for example, our three earlier articles Crows out-tool chimps; Jumbo minds: elephants are proving just as smart as chimps in many areas if not smarter; and Bird-brain matches chimps (and neither makes it to grade school).

Fish biologists, too, have known now for some time that fish aren’t dimwits with a ‘sea change’ among researchers in their conceptions of the cognitive abilities of fish:

‘Gone (or at least obsolete) is the image of fish as drudging and dim-witted peabrains, driven largely by “instinct”, with what little behavioural flexibility they possess being severely hampered by an infamous “three-second memory”.’2

Instead, goldfish memories are now known to last at least three months, and Australian crimson spotted rainbowfish, which learned to escape from a net in their tank, remembered how they did it 11 months later.3 As one fisheries biologist put it:

‘Fish are more intelligent than they appear. In many areas, such as memory, their cognitive powers match or exceed those of “higher” vertebrates, including non-human primates.’4

So much for the ‘evolutionary progression’ idea that puts fish down the ‘lower’ end of vertebrate evolution!

What about documented evidence of ‘intelligence’ in invertebrates (animals without backbones) such as crabs and other crustaceans?

In fact, new-found evidence of ‘smart’ lobsters is surprising many people, and it has come to light through a somewhat unusual turn of events.

Watching lobsters

At a time when stocks of many commercial fisheries species are diminishing, scuba surveys found plenty of lobsters on the seabed of the North American lobster fishery. But the surveys didn’t match the data from lobster fishing.

So University of New Hampshire zoologist Win Watson attached an underwater video camera to a standard commercial lobster trap and lowered it to the seabed. It had been thought that the traps were pretty effective, with lobsters entering through a funnel-shaped opening, and, after dining on the bait placed inside, it was thought they would have great difficulty finding their way back out through the narrow end of the funnel.

But Professor Watson’s videotape showed otherwise.5 His expectation had been, given that traps hauled to the surface usually contained only a handful of lobsters, that the video would show only a modest number of lobsters approaching the trap. But when he and other researchers looked at the first time-lapse images from their trap-mounted video camera, they were ‘totally stunned’ by what they saw.

‘The numbers of lobsters were just amazing,’ explained Watson. ‘It looked like an anthill,’ he said, as lobsters could be seen scuffling all over the trap.

But the ‘biggest surprise’ was that the videos showed lobsters of all sizes crawling in and out of the funnel-shaped entrance ‘as they pleased’—‘happily wandering in and out of the traps at will’.6

As an article in the University of New Hampshire’s online magazine put it:

‘[A] mere 6 percent of the lobsters who entered were caught, largely because they had the bad luck to be in the trap when it was hauled up. Instead of a Crustacean Hotel where the lobsters would “check in and never check out”, the lobster trap works more like a 24-hour roadhouse where the patrons are generally free to leave—usually through the supposedly one-way entrance.’7

The commercial fishermen who earn their living by catching lobsters were just as surprised when they viewed the video. ‘It’s pretty discouraging to think that here we, as intelligent human beings, have been trying our best to harvest this thing that has no brain to speak of and they’re outsmarting us,’ observed Pat White, of the Maine Lobstermen’s Association.6,8,9

In the lab, Watson has confirmed that lobsters do indeed have what it takes to recognize, and remember, left from right—they successfully negotiated a maze that Watson and his colleagues constructed to test them. Clever crustaceans!

What’s more, researcher Diane Cowan says that lobsters are ‘highly social’, and:

‘They know where their neighbors live and know what molt stage they’re in. It’s not just whether an animal has a backbone or not that makes it simple or complex.’

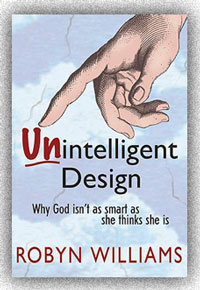

Wise words, yet such is the hold that the evolutionary paradigm has on many people, an animal without a backbone (i.e. an invertebrate) would normally be considered way down the intelligence scale (compared to the vertebrates). One such likely ‘victim’ of his own (unquestioning?) acceptance of evolution is Australian Broadcasting Corporation science journalist Robyn Williams, well-known atheist and stridently anti-creationist.10 He is the author of Unintelligent Design—Why God isn’t as smart as she thinks she is.11 In a recent interview12 with University of Tasmania fisheries biologist Caleb Gardner, Williams asked as to why the North American lobster fishery is thriving, while other fishery species seem to be in demise:

Caleb Gardner: One [idea] is that there is effectively enhancement of the stocks up there just through bait. The amount of fishing effort that’s going into North America is phenomenal in some areas, and you can just see these areas where you can almost walk from buoy to buoy, there are that many pots [traps] in the water in some places, and so the amount of bait going into the ecosystem there is also quite massive. There’s a thought that that may be supplementing the diet of lobsters and helping effectively farm them almost; you’re feeding the lobsters and being able to catch more.

Robyn Williams: How amazing. One wonders how the bait gets out of the trap.

Of course Caleb Gardner explained to Williams that it was the lobsters that were able to get in and out of the traps ‘amazing easily’ (i.e. eating the bait without getting caught). He went on:

Caleb Gardner: That’s one of the other interesting things about that North American fishery. They have very beautiful traps, a lot of effort goes into building these things, they’re quite works of art. Of course the intent is to try to keep the animals in the trap, but they really aren’t very effective at that at all. So there’s all this effort going into making all these beautiful constructions and the lobsters are just wandering in and out as they please, effectively.

Just as making the traps, and putting the bait in them, required (human) intelligence, surely getting the bait out of the traps (without getting caught) also required (lobster) intelligence?

And the source of that intelligence? Clearly the Designer of both human and lobster had to be more intelligent than both. Much more intelligent than Mr Williams has been willing to give Him (not ‘her’) credit for. Yet. (Romans 14:11)

References

- Note that while it’s possible to grade organisms on the basis of their complexity (i.e. from ‘less complex’ to ‘more complex’), the gradation in complexity has nothing to do with alleged evolutionary progression. (In the same way, one could grade kitchen cutlery on the basis of ‘complexity’, but that does not mean that the fork evolved from a spoon, for example.) Return to Text.

- Laland, K., Brown, C., and Krause, J., Learning in fishes: from three-second memory to culture, Fish and Fisheries 4:199–202, 2003. Return to Text.

- The research paper reporting this result said it ‘is comparable to the long-term maintenance of hook shyness in carp and salmon for over a year’. Brown, C., Familiarity with the test environment improves escape responses in the crimson spotted rainbowfish, Melanotaenia duboulayi. Animal Cognition 4:109–113, 2001. Return to Text.

- India Daily, Experiments reveal fishes are getting extremely intelligent—will they replace humans as Intelligent beings on the earth?, <http:www.indiadaily.com/editorial/1849.asp>, acc. 25 May 2006. Return to Text.

- CBC News, Great lobster escapes caught on camera,

<http://www.cbc.ca/health/story/2003/01/10/

lobsters030110.html>, pub. 27 February 2003, acc. 4 January 2008. Return to Text. - Woodard, C., Lobsters on a roll: new research reveals that lobsters are too smart for fishermen’s traps—they’re dining and going home, The Christian Science Monitor, <http://www.csmonitor.com/2003/0109/p11s02-sten.html>, pub. 9 January 2003, acc. 4 January 2008. Return to Text.

- Stuart, V., Crustaceans with attitude, University of New Hampshire Magazine Online, <http://unhmagazine.unh.edu/sp04/crustaceans.html>, pub. Spring 2004, acc. 4 January 2008. Return to Text.

- Actually, crustaceans do have a ‘brain’, but biologists

describe the neurons as being organized very differently from that of a human brain.

Museum Victoria information sheet: ‘Where is a crustacean’s brain?’,

<http://museumvictoria.com.au/DiscoveryCentre/

Infosheets/Where-is-a-crustaceans-brain>, acc. 20 January 2008. Return to Text. - Even the smallest invertebrates, with limited space for neurons, have surprised researchers who quite reasonably expected their brains to be ‘functionally inferior’—the researchers saw no evidence of any ‘handicaps of minaturization’ whatsoever. See Good design in miniature. Return to Text.

- Robyn Williams was declared the Australian Humanist of the Year in 1993. Return to Text.

- Publishers: Allen and Unwin, Crows Nest, NSW, Australia, 2006. Return to Text.

- ABC Radio National’s The Science Show, Lobsters

on the increase in Tasmania, <http://www.abc.net.au/rn/scienceshow/stories/2007/

2119490.htm>, broadcast 15 December 2007, acc. 4 January 2008. Return to Text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.