Honey

A healing gift from the Creator

In A.A. Milne’s classic stories, the bear Winnie-the-Pooh always had his priorities in order—an order of one, ‘Hunny!’ This was a good order, but not for the reason he supposed. He was unaware of the wonderful medicinal properties of raw1 honey.

From the earliest post-Flood times, ancient near-eastern cultures believed that honey was a gift from the gods. These descendants of Noah were aware that honey had medicinal properties: surviving records show how the ancient Egyptians used honey to prevent and cure various diseases, and heal wounds.2

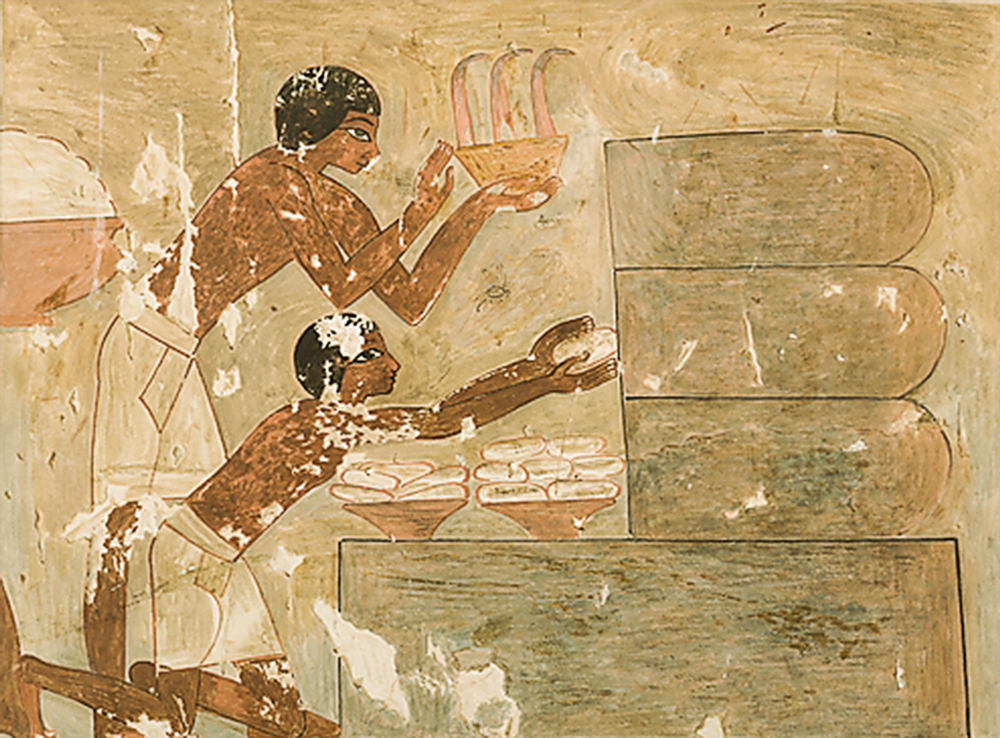

The first known official recognition of the importance of honey dates from the very beginnings of Pharaonic Egypt—the use of the title ‘Sealer of the Honey’.3 Egyptians involved in honey production were also known as ‘Bee keepers/Honey gatherers’ [  ] (Egy. bityw). Fig. 1 depicts Egyptian bee keepers, from three thousand years ago, tending a hive.

] (Egy. bityw). Fig. 1 depicts Egyptian bee keepers, from three thousand years ago, tending a hive.

Honey doesn’t make itself

Most of us know that bees make honey. But did you know that there are over 20,000 species of bee? Yet only seven of these species are honeybees.

First, the honeybee must seek and collect nectar from suitable flowers—a massive undertaking in itself. The nectar, a thin, easily spoiled, sweet liquid, is transformed (‘ripened’) by the honeybee to a stable, high-density, high-energy food.

Honeybees have two stomachs, a honey stomach, which is used to hold nectar, and the regular stomach. When full, the honey stomach holds approximately 70 mg of nectar and weighs almost as much as the bee. Honeybees visit as many as 1500 flowers in order to fill their honey stomachs. On the way back to the hive, they add enzymes to the nectar which begins its conversion to honey.

The Bible and honey

The Bible contains many references to honey, such as:

The honey we eat is essentially nectar that honeybees have repeatedly regurgitated (sometimes into another bee’s mouth, or directly into the honeycomb) and dehydrated. This drying process is accelerated through worker bees flapping their wings to drive off moisture once in the honeycomb.

Honey is a concentrated water solution of two sugars, glucose and fructose, with smaller amounts of over twenty more-complex sugars. It also contains some acids which, though small in amount (<0.5%), play an important role in the stability of honey against microorganism attacks. As well as the enzymes, it also contains trace amounts of essential minerals. It takes some 300 honeybees to manufacture 450 grams (one pound) of honey, involving a total flying distance of twice around the earth!

Equipped with 60,000 olfactory (smell) receptor cells on the antennae5 packed into 170 olfactory receptors,6 and a brain smaller than a sesame seed, the common honeybee is able to locate, transport, and transform nectar into honey. This would be amazing enough—but the cleverest bit is yet to come!

Killing germs

Throughout the ages, people with open wounds have run the risk of serious infection spreading into their body, and even death. The ancients often used honey-based treatments to cure and heal wounds and other infections. Modern insights into honey’s amazing properties are revealing. Raw honey contains five compounds which provide honey with an amazing antibacterial ‘clout’. These are:

Glucose oxidase and bleach (hydrogen peroxide)

As honeybees process their honey they add an enzyme called glucose oxidase as a preservative. On contact with free water, this enzyme produces, from the sugar glucose, a slow release of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). This chemical is an alternative to chlorine bleach used in household whitening and disinfecting. It disinfects by rapidly oxidizing components on the outside of bacteria, killing them by creating holes in the cell membrane.

The reaction this enzyme facilitates is easy to follow:

C6H12O6 (glucose) + H2O(water) + O2 (oxygen) → C6H12O7(gluconic acid)+ H2O2 (hydrogen peroxide)

All raw honey contains glucose oxidase, also called ‘notatin’.

Methylglyoxal

Honey made from the nectar of the Tea Tree (or Manuka Tree) blossom can contain large amounts of dietary methylglyoxal (CH3C(O)CHO). In 2006, Thomas Henle discovered that this enzyme gives Manuka honey its unique antibacterial and antiviral properties. Later, Henle added that dietary methylglyoxal in this honey was stable within the mouth, throat and stomach where it can kill disease-causing bacteria. Upon reaching the small and large intestines, methylglyoxal broke down into lactic acid (CH3CH(OH)COOH), so this antibacterial, according to Henle, “is not absorbed into the body and does not pose a dietary risk for consumers … .”7

In the lab, no bacterium or virus has so far been shown to be resistant to high levels of methylglyoxal—including many of the so-called ‘superbugs’ that have become resistant to man-made antibiotics.8

Apidaecin

Apidaecin9 is made by honeybees, and its presence is very rapidly lethal for many gram-negative10 bacteria.

Bee defensin-1

For many years this defensin11 was thought to exist only in bee ‘Royal Jelly’.12 Recently it was discovered to be a key component of honey, too. This compound punctures the bacterial membrane, causing the cell contents to leak out, killing the bacterium.

Hospitals and honey

In the last few years, clinical trials have been undertaken in major hospitals using medical-grade forms of un-heat-treated honey13 in healing wounds, especially in patients whose immune system is compromised. Initial results are promising.14

Bee amazed – fascinating facts

Communication

Bees use a ‘waggle’ dance, an extraordinary way to tell other bees where to find nectar—see Dancing bees, Creation 17(4):46–48, 1995.

Swarm decision-making

When scouts report potential new hive sites, the swarm uses competitive group ‘dance offs’ to eliminate poorer options and choose the best hive site—see How bees decide, Creation 30(1):19, 2007.

Navigation

Bees have biological airspeed gauges, gyroscopes, compasses and more, enabling precision flying and navigation—see Can it bee? Creation 25(2):44–45, 2003; creation.com/can-it-bee. They use a form of ‘optic-flow’ monitoring to land safely hundreds of times a day, on widely-varying surfaces. Scientists are racing to apply this discovery to drones and other pilotless aircraft—see Bees’ guidance strategy for avoiding crash landings, Creation 36(3):56, 2014.

Computation

The notorious ‘travelling salesman problem’—finding the shortest route between multiple locations—can keep supercomputers busy for days. Yet the tiny brain of the bee routinely solves such problems for hundreds of locations. See Bees outsmart supercomputers, Creation 33(3):56, 2011.

Pollination

Pollen is produced by the flowers of seed plants, and contains the plant’s male genetic material. When transported by bees and other insects, pollen from one flower is able to fertilize the female part of a different flower, called cross-pollination. This is most useful for greater genetic diversity.

Bees are efficient pollinators, as pollen readily sticks to their fuzzy exterior. They also deliberately collect pollen in special structures on their hind legs. This is not for making honey, but as a protein source for feeding their larvae.

Summary and conclusion

Honeybees do not have the benefit of a university education, yet they perform the multiple, complex functions needed to produce honey (navigation, flower identification, etc.), and handle complex organic chemistry with ease.

Such complexity does not arrive by fortunate happenstance. Honeybees operate using pre-installed programs that only work if all the elements are in place from the word ‘go!’

Honeybees’ inbuilt navigational ‘sat-nav’, for example, is far more efficient than any human equivalent—think of all those news reports where humans programmed their GPS devices and promptly got lost! And honeybees’ antibacterial components often have the edge over manmade versions.

Honey—God’s sweetener, and medicine—is surely one more evidence that “his invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made. So they are without excuse” (Romans 1:20).

References and notes

- I.e. straight from the extractor; not pasteurized (heat-treated) like that on most supermarket shelves. Of course pasteurization is important in preventing transmission of certain diseases in many types of food, including honey. However, along with destroying any harmful microbes, heating will also tend to destroy the antibacterial chemicals that make honey useful in e.g. wound healing. Return to text

- Papyrus Ebers (University of Leipzig); Papyrus Brugsch (Berlin Museum, papyrus Berlin 3038); Kahun Medical Papyrus (University College London, UC32057); all contain honey-based prescriptions and treatments. Return to text

- Ransome, H.M., The Sacred Bee in Ancient Times and Folklore, p. 26, Courier Dover, 2004. Return to text

- Gathering Honey, Tomb of Rekhmire, metmuseum.org, accessed December 2014. Return to text

- Galizia, C.G. and Menzel, R., Odour perception in honeybees: coding information in glomerular patterns; Current Opinion in Neurobiology 10(4):504–510, 2000. Return to text

- Robertson, H.M. and Wanner, K.W., The chemoreceptor superfamily in the honey bee, Apis mellifera: Expansion of the odorant, but not gustatory, receptor family, Genome Research 16(11):1395–1403, November 2006. Return to text

- See manukahealth.co.nz, Manuka honey ‘safe to eat’; accessed 3 April 2014. Of course it also means that by this route, it is unable to deal with systemic infections, unlike clinically used oral antibiotics which are absorbed and then carried in the blood to sites of infection. Importantly, therefore, antibacterial action in the lab, while it may be important in healing open wounds and preventing their spread into the tissues, does not necessarily translate into being able to kill bacteria that have already actively invaded tissue. Return to text

- These are neither ‘superior’, nor the result of ‘evolution’; see Wieland, C., Superbugs not super after all, Creation 20(1):10–13, 1997; creation.com/superbugs. Return to text

- Actually a group of compounds, the apidaecins. They are peptides, which refers to chains of amino acids that are too short to be called proteins. Return to text

- ‘Gram-negative’ simply refers to a particular staining characteristic under the microscope. Such types of bacteria are commonly found in the human digestive tract and include Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Helicobacter pylori, the latter now known to cause ulcers. Return to text

- A term for a group of antibacterial chemicals produced by insects. Return to text

- A special type of secretion from the glands of bees tending the developing larvae. Feeding them large amounts of this triggers the development of some larvae into queen bees. Return to text

- Such as Surgihoney™ and Medihoney™. Other honeys used recently in medical treatment trials include Manuka honey and Tualang honey. Return to text

- E.g. see Ingle, R.et al., Wound healing with honey—a randomised controlled trial, S. Afr. Med. J. 96(9):831–5, 2006; ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17068655. See also ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2686636. Return to text

- Longgood W., The Queen must die: and other affairs of bees and men, Norton Publications, New York, 1985. Return to text

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.