Parrot of the night—NZ’s kakapo

The isolated islands of New Zealand harbour much ‘oddball’ birdlife. Among these is the kakapo1—heavyweight of the parrot world. Once, the countryside teemed with these moss-green, ground-dwelling parrots. But today, only about 90 specimens survive—serious contenders for the title of ‘world’s rarest bird’. Weighing in at an impressive 3.5 kg and with no mammalian predators, the kakapo were once numerous in New Zealand. The only threat it faced was the giant Haast eagle2 and this danger was avoided by simply standing stock still in the camouflaging undergrowth.

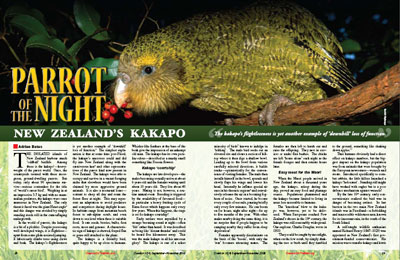

In the world of parrots, the kakapo is a bit of a plodder. Despite possessing well developed wings, it is flightless—apart from some glide-assisted jumping. It laboriously climbs trees using claws and beak. The kakapo’s flightlessness is yet another example of ‘downhill’ loss of function.3 The simplest explanation is that at some time post-Flood, the kakapo’s ancestors could and did fly into New Zealand along with the carnivorous kea4 and other representatives of the parrot kind now present in New Zealand. The kakapo were able to occupy and survive in a vacant foraging niche that elsewhere would have been claimed by more aggressive ground animals. It is also a nocturnal loner—content to sleep all day and roam the forest floor at night. This may represent an adaptation to avoid predators and competitors during daylight hours. Its habitats range from mountain beech forest to sub-alpine scrub, and even down to sea level when there is suitable food. It eats seeds, berries, bulbs, fern roots, moss and grasses. A characteristic sign of kakapo is chewed, frayed flax or grass still attached to the plant.

The kakapo is a friendly bird, quite happy to be up close to humans. Whisker-like feathers at the base of the beak give the impression of an unkempt old man. The kakapo has its own peculiar odour—described as a musky smell something like Freesia flowers.

Kakapo ‘courtship’

The kakapo are late developers—the males becoming sexually active at about 6 years old and the females waiting until about 10 years old. They live about 40 years. Mating is not, however, a routine annual event. Breeding is triggered by the availability of favoured food—in particular a heavy fruiting cycle of Rimu forest which happens only every few years. When this happens, the stage is set for kakapo courtship!

Early settlers were mystified by a strange booming sound at night—often ‘felt’ rather than heard. It was described as being like ‘distant thunder’ and could be heard five kilometres away. This was the male kakapo in all his amorous glory! The kakapo is one of a select minority of birds5 known to indulge in ‘lekking’. The male bird seeks out an elevated site and clears a section of hilltop where it then digs a shallow bowl. Leading up to the bowl from various carefully selected directions, it builds tracks—optimistically for the convenience of visiting females. The male then installs himself in the bowl, spreads and slowly flaps his wings and lowers his head. Internally he inflates special air sacs in his thoracic regions6 and convulsively releases the air in a booming foghorn of noise. Once started, he booms every couple of seconds, pausing briefly only every few minutes. He can boom on for hours, night after night—for up to five months of the year. With other males nearby doing the same thing, it is no surprise that if people happen to be camping nearby they suffer from sleep deprivation!

Females apparently discriminate on the basis of the ‘boom’, with only the ‘star’ boomers attracting mates. The females are then left to hatch out and raise the offspring. They nest in crevices or under flax bushes. The chicks are left ‘home alone’ each night as the female forages and then returns hours later.

Easy meat for the Maori

When the Maori people arrived in New Zealand about a thousand years ago, the kakapo, asleep during the day, proved an easy food and plumage source. Populations plummeted and the kakapo became limited to living in areas less accessible to humans.

The ‘knockout’ blow to the kakapo was, however, yet to be delivered. When Europeans reached New Zealand’s shores in the 18th century, the kakapo was still reasonably widespread. One explorer, Charlie Douglas, wrote in 1899:

‘They could be caught by moonlight, when on the low scrub, by simply shaking the tree or bush until they tumbled to the ground, something like shaking down apples.’7

Thus humans obviously had a direct effect on kakapo numbers, but the biggest impact on the kakapo population was from animals that were brought by the European newcomers—weasels and stoats. Introduced specifically to combat rabbits, the little killers launched a kakapo ‘holocaust’. Standing still might have worked with eagles but is a poor defence mechanism against weasels!

By the late 19th century, early conservationists realized the bird was in danger of becoming extinct. Its last bastion in the two main New Zealand islands was in Fiordland—a forbidding and inaccessible wilderness area, known for its incessant rain, in the south of the South Island.

A self-taught wildlife enthusiast named Richard Henry (1845–1929) was appointed as New Zealand’s first government-funded conservationist. His mission was to transfer kakapo and kiwis (another flightless bird species) from the surrounding mainland to an island haven in a fiord named Dusky Sound. This remarkable man succeeded in his task. In the first six years he relocated some 700 birds to Resolution Island, with the help of a specially trained dog. His meticulous observations of kakapo habits have proved invaluable to later conservationists.

However, after 14 years of dedicated effort, while rowing around the island one day, Richard Henry was shocked to observe on one of the beaches … a weasel! He realised that all his hard work was doomed to failure and so it proved. Subsequently sporadic efforts were made to transfer birds to other outlying NZ islands, but then came two world wars when conservation necessarily had a lower priority.

The kakapo holds on

In the 1970s the kakapo was supposedly extinct, having disappeared first from the North Island then from the South Island—the last bird being seen near Milford Sound. But in 1977, in a sensational discovery, kakapo were found still surviving on New Zealand’s southernmost major island—Stewart Island. But this colony of approximately 200 birds was vulnerable to feral cats. The decision was made to attempt relocation to other (cat-and weasel-free) islands and a total of 61 birds were successfully moved.

Today, the 90 or so surviving kakapo serve as a useful teaching example of how to view the world from the standpoint of biblical history:

- The kakapo is a parrot, descended from representatives of the original created parrot ‘kind’.

- In contrast to the first parrots arriving (by air) in New Zealand after the Flood (possibly not very many generations after parrots came off the Ark), the kakapo is flightless. This represents a loss of information, not a gain, and therefore is not evolution (in the sense of the claim that pond scum became parrots).

- Kakapo moved into a vacant ecological niche in New Zealand that on other continents would have been occupied by ground animals. In the absence of ground-dwelling predators (absent because they were unable to make the sea crossing), kakapo survived (in stark contrast to flightless parrot mutants on other continents) and multiplied.

- With the arrival of ground predators, the increased forces of ‘natural selection’ soon impacted New Zealand’s population of birds that had lost the ability to fly—including the kakapo.

- The flightless kakapo as a species is therefore in danger of extinction, in common with many other animal and bird species around the world—a reminder that we live in a sin-cursed world ‘in bondage to decay’ (Romans 8:19–22) with death an ever-present reality. This is in stark contrast to the original ‘very good’ world in which there were no mutations, and so no death of the unfit.

References and notes

- Maori meaning ‘night parrot’; Latin name Strigops habroptilus. Return to text.

- The Haast eagle was the world’s largest eagle, but has been extinct since c. AD 1400. Return to text.

- See, e.g., Wieland, C., Beetle bloopers even a defect can be an advantage sometimes, Creation 19(3):30, 1997; <creation.com/beetle>. Return to text.

- See: Weston, P., Air attack Kea: clever, clownish and carnivorous!?, Creation 27(1):28–32, 2004; <creation.com/kea>. Return to text.

- Approximately 50 species of birds worldwide. The kakapo is the only parrot to ‘lek’. Return to text.

- The kakapo is the only parrot to do this. Return to text.

- Kakapo recovery program, Then and now, decline, <www.kakaporecovery.org.nz/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=77&Itemid=168>, 16 June 2008. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.