Feedback archive → Feedback 2016

The rock cycle

How do we handle it?

Today’s feedback comes from Dan B. of the UK, who asked for help about the geological rock cycle in his daughter’s school curriculum.

We’ve just received the science curriculum my daughter will be following as she moves into Year 8 (i.e. when students turn 13 in the UK school system). It includes the topic of the “rock cycle” to which a few CMI articles make passing references but none appear to give explicit treatment. It seems to be a key concept in long-age historical geology. How should Christians think biblically about it, and how might parents best handle it with their children as they are taught it at school? Is it one to which we can give qualified limited assent, except that it involves excessive extrapolation into the past? I was never taught any geology in school science, including A-level physics and chemistry. Yet here is this concept introduced at an earlier stage, before any curricular discussion of biological evolution.

CMI geologist Tasman Walker responds:

Hi Dan,

Yes, the rock cycle is a key concept in long-age ‘historical’ geology. As you discovered, geological concepts are introduced to students early in the curriculum within the long-age worldview. By presenting the rock cycle in a long-age framework naturally prepares students for other evolutionary ideas.

The rock cycle is like many other concepts related to evolution and long ages. There are some aspects of the ‘cycle’ that are reasonable, which can be supported, and there are other aspects that involve eons of time, which need to be recognized and reinterpreted.

The original rock-cycle concept is credited to the Scottish physician James Hutton (1726–1797), who is regarded as a founder of modern, long-age geology. (See articles on Hutton, on The Man Who Found Time and Siccar Point.) The aim of the cycle is to describe the relationship between the three basic rock types: igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic. There are many versions of the rock-cycle concept around these days.

Many cycles exist in the natural world, such as the water cycle, the life cycles of insects, of other animals, and the nitrogen cycle. These cycles operate over periods of weeks, months and years, and as such can be observed and studied. The rock cycle, on the other hand, is envisaged to operate over timescales of millions of years, and as such it cannot be observed. The validity of the other cycles tends to give the long-age rock cycle credibility and implies that it is still operating, but it is not.

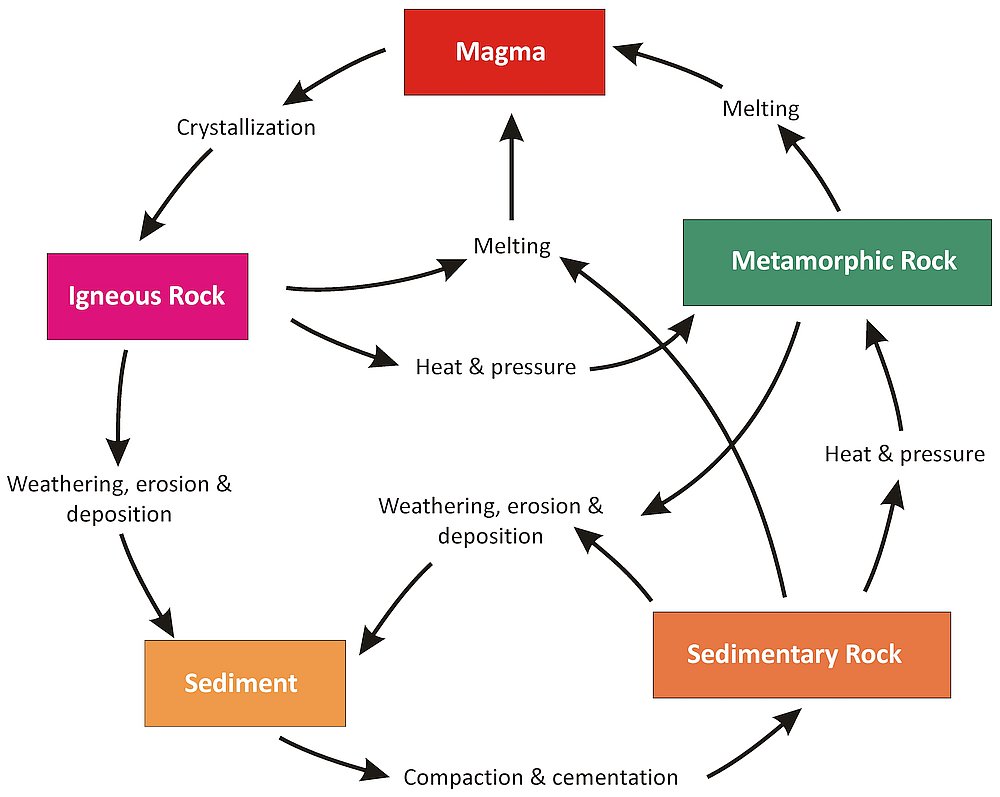

The figure at right shows a typical version of the rock cycle. It has a box for each type of rock, “Igneous rock”, “Sedimentary rock”, and “Metamorphic rock”. Also shown is a box for “Sediment”, which is a step on the way to sedimentary rock, and “Magma”, or molten rock, which is a step on the way to igneous rock.

This diagram shows how each kind of rock can change into other kinds of rock:

- Sedimentary rock can change into metamorphic rock, igneous rock, or even different sedimentary rock. The process of change is weathering, erosion, deposition, compaction and cementation.

- Igneous rock can change into sedimentary rock, metamorphic rock, or even different igneous rock. The process of change is melting and crystallization.

- Metamorphic rock can change into sedimentary rock, or igneous rock. It can also change into different metamorphic rock but this is not shown on the diagram. The metamorphic change is driven by heat and pressure.

The basic philosophy of long-age geologists is that the rocks of the earth formed under conditions similar to what we see on earth at the present time. Consequently the diagram mentions processes that we see happening today. For example, we see rocks weathering and eroding and producing sediment. We see sediment cementing into sedimentary rock. We see magma erupt from volcanoes and crystallize into rock. These processes are reasonably small-scale compared with the size of the earth, and do not have much geological impact. Consequently, to produce the enormous volume of rock we see on the earth, James Hutton assumed that geological processes continued over eons of time. That is why he imagined the world was infinitely old.

So, the rock cycle suggests rocks keep changing from one form into another in endless cycles, going on and on forever. James Hutton said that he saw “no vestige of a beginning and no sign of an end”. These slow, endless cycles Hutton imagined are similar to the Hindu concept of eternal cycles of nature.

The rock cycle has been modified since Hutton first proposed it. Developments in thermodynamics in the late 1800s meant that the cycle could not have been going on endlessly, but it is still considered to have operated for eons of time. With the advent of plate tectonics in the 1960s the repetitive rock cycle changed into a gradually evolving process.

Geologists who begin with the Bible have a different way of understanding the geology of the world. Most have concluded that, at a minimum, most of the fossil-bearing rocks on the earth formed during the year-long Noah’s Flood. (See The geological column is a general Flood order with many exceptions.) In other words, most of the rocks on earth formed quickly, within that year-long event. (Some biblical geologists consider that some rocks on the Earth formed during Creation Week, and as a result of regional catastrophes in the years immediately after the Flood, but these too would have formed quickly.)

Therefore, from a biblical perspective the processes indicated on the rock cycle were rapid, and formed mostly in catastrophic events, especially the year-long Flood. Rocks melted and crystallized into igneous rocks. This happened quickly. Rocks were buried and metamorphosed; this also happened quickly. Rocks were eroded, transported, and deposited as sediment, which was then compacted and cemented into rock. This too all happened rapidly.

The term “weathering” on the diagram is not appropriate because it implies slow disintegration of rocks due to the weather. However, the rocks would have eroded very rapidly during the Flood (and on a smaller scale in post-Flood catastrophes) by processes such as cataclysmic water flows. Weathering as we know it today is only valid in the c. 4,000 years since the Flood and the immediate post-Flood era, and this has only had a tiny comparative effect on the geology.

So, we can support the idea that rocks changed from one into the other, but this mostly happened during Creation Week, the year-long Flood, and (on a smaller scale) in post-Flood regional catastrophes. We can accept the geological processes of erosion, deposition, compaction, cementation, melting, crystallization, and metamorphism (due to heat and pressure). We would not accept “weathering” as a significant process explaining most of the rock record, but we accept that it has occurred since the Flood. We can accept that there were multiple ‘cycles’ that would have occurred during the year-long Flood. These would have been driven by movements of the earth’s crust and enormous flows of water. Rocks would have melted, crystallized, eroded, been buried, and metamorphosed over and over again. However, these ‘cycles’ came to a stop when the Flood ended, barring residual smaller-scale catastrophes occurring as the globe returned to a state of equilibrium in the years after the Flood. The geological processes we see today are relatively small compared with what happened during such catastrophic events, especially (and primarily) the Flood.

I hope that is helpful for you,

Tas Walker

Scientist, writer, speaker

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.