Abraham Ulrikab—the ‘zoo exhibit’ who could write

Creation readers may recall the story of Ota Benga—the pygmy taken from his home in Africa in 1904 and showcased in a US zoo as an example of an evolutionarily ‘primitive’ race.1 His story was not unique; from about 1870 to 1940, “travelling exhibits of non-European natives were recurring features of zoological gardens where they eclipsed the drawing power of the more usual animal exhibits.”2

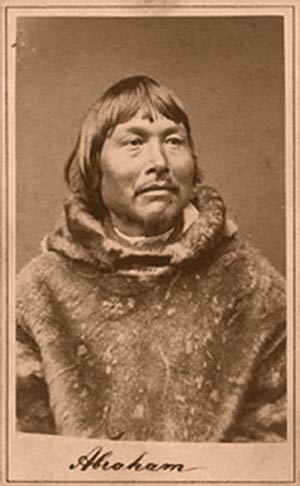

Abraham Ulrikab was an Inuit (formerly called ‘Eskimo’) whom Moravian missionaries in Hebron, Labrador (Canada), counted among their converts. He and several of his fellow Inuit were one of many so-called ‘primitive’ people to be shown in zoos throughout Europe and North America in that era, showcased as examples of inferior stages of ‘evolutionary progress’.3

Abraham’s ill-fated Atlantic trip

Adrian Jacobsen, a Norwegian trader in people and artefacts from other cultures, had made a fortune in 1877 by exhibiting Inuit from Greenland around Europe, returning them home safely after a successful tour. However, the Danish government subsequently forbade him from using Greenland Inuit anymore for such purposes. So Jacobsen looked to Labrador, on the North American continent.

However, the missionaries in Hebron were steadfastly against the idea of Jacobsen taking their Inuit parishioners away. So he hired Abraham Ulrikab as an interpreter, and set sail for a nearby Inuit colony that had refused Christianization. With Abraham’s help Jacobsen managed to convince Terrianiak and Paingo, a young couple with a teenage daughter, to come with him. But still short on numbers, he asked Abraham and his family to come.

Abraham knew the missionaries were against the idea. For one thing, they believed that exhibiting people like zoo animals was immoral.4 But the 35-year-old Abraham had a sense of curiosity and adventure. He also had a debt of 10 pounds to the mission, and saw the trip as a way of paying it off.

So along with his wife 24-year-old Ulrike, their two young children, his nephew Tobias and Terrianiak’s family, they set sail for Germany in August of 1880. Abraham, who has been described as “literate and honest … admired for his penmanship, drawing skills, and work ethic”, began keeping a diary, full of “strength and sorrow”. The voyage soon caused him concern and disappointment; his nephew Tobias was severely beaten with a dog whip by a “furious Jacobsen” for “disobedience”.4

Despite this, the Inuit were excited upon their arrival in Europe. But it didn’t take long for them to become both sick and homesick, and tired of their expedition, especially the zoo crowds. Contrary to promises of a ‘scientific purpose’, it soon became clear that the real purpose was to be an exhibit for paying customers. “They were exposed in public zoos much the same as animals.”4 Not long after their first appearance at the Berlin zoo, even one of the local newspapers wrote an editorial against the practice, as “decidedly repulsive”.4

Failure to vaccinate

Unfortunately, for various reasons, Jacobsen had failed to immunize the eight Inuit against smallpox. After the teenage daughter of the Terrianiak family and her mother had succumbed to the fatal disease in mid-December 1880, his efforts to then vaccinate were too late. About four weeks later, they had all died of smallpox, with Abraham’s 24-year-old wife Ulrike the last to go.

We would probably have no knowledge of this ill-fated venture if Abraham Ulrikab had not kept a diary record of his perceptions and experiences.3 He and his family were devout Christians, and this comes through prominently in his words. An intelligent man, he had been taught to read and write by the Moravian missionaries, and was the violinist for the Hebron congregation. As well as a being a fluent writer in his native Inuktitut (his diary was in this language, later translated by one of the missionaries), he could speak some German and English.

Abraham Ulrikab’s records

A constant theme of Abraham’s recollections was the large size of the crowds. They seemed very condescending, being astonished that this ‘primitive’ man could even write his own name. Yet those same crowds often displayed unruly behaviour that shamed this so-called ‘primitive’ person.

One episode in particular stands out in his diary. A crowd had gone right out of control:

“… everything was filled with people and it was impossible to move anymore. Both our masters Schoepf and Jacobsen shouted with big voices and some of the higher-ranking soldiers left but most of them had no ears. Since our two masters did not achieve anything, they came to me and sent me to drive them out. So I did what I could. Taking my whip and the Greenland seal harpoon, I made myself terrible. One of the gentlemen was like a crier. Others quickly shook hands with me when I chased them out. Others went and jumped over the fence because there were so many. … Ulrike had also locked our house from the inside and plugged up the entrance so that nobody would go in, and those who wanted to look in through the windows were pushed away with a piece of wood.”

He was forced to act in a manner that reinforced the popular perception of him and his people as ‘uncivilized brutes’ in spite of the fact that if any were acting like animals, it was the European crowd.

Maintaining faith

When the first of his small group started dying of smallpox, Abraham saw that he too was likely to die. By this time weary of Europe, he wrote:

“I do not long for earthly possessions but this is what I long for: to see my relatives again, who are over there, to talk to them of the name of God as long as I live.”

Nevertheless, he committed his way to the Lord, whether he lived or died:

“My dear teacher Elsner, pray for us to the Lord that the evil sickness will stop if it is His will; but God’s will be fulfilled. I am a poor man who’s dust.”

In the circumstances, Abraham’s courage and faith were admirable despite the obvious sadness in his words. He maintained faith in the Lord throughout, even with his family perishing from smallpox around him.

Abraham’s words offer a sobering gaze at the effects of evolution on human relations. He and his fellow Inuit, like so many other people groups, were treated as subhuman commodities on the basis of ‘science’, to be gawked at for profit.

The irony is, that of the thousands with whom he came in contact on his journey, Abraham Ulrikab was perhaps the most civilized of them all.

References

- Bergman, J., Ota Benga, Creation 16(1):48–50, 1993; creation.com/ota-benga. Return to text.

- Jonassohn, K, On A Neglected Aspect Of Western Racism, presented to the Association of Genocide Scholars meeting in Minneapolis, 9-12 June 2001, migs.concordia.ca/occpapers/zoo.htm. Return to text.

- Lutz, H. (ed.), The Diary of Abraham Ulrikab: Text and Context, University of Ottawa Press, Ottawa, Canada, 2005. Return to text.

- www.suite101.com/content/inuit-peoples-recruitment-from-labrador-canada-a173014, accessed 5 February 2011. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.