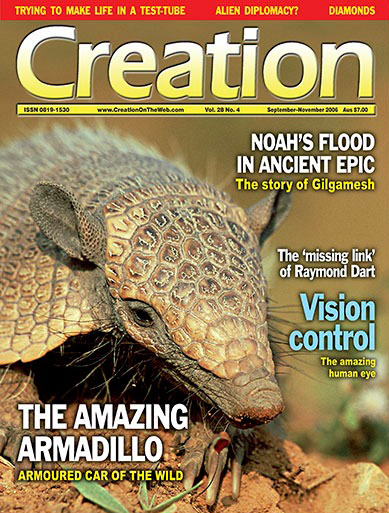

Amazing armoured armadillos of the Americas

One afternoon at my friend’s home in Texas (south-western USA), as his family were welcoming some visitors, an armadillo came into view. The guests were wary of the animal, but my friend’s mother assured them that they were harmless, other than being possible carriers of leprosy. (See below.) One of the young female guests began jumping and screaming, worried that the animal would attack her. My friend’s mother tried to reassure her, pointing out that since armadillos are nocturnal, the little creature was not able to see her well in the bright light and was not attacking. Armadillos are timid creatures, and this one would keep his distance, she said.

The commotion from the guests frightened the armadillo. He turned away from the hysterical young ladies, charging straight for the mother. Having chairs on her left and mud on her right she had no place to go but up—she jumped in the air as the armadillo ran beneath her. All of this was accompanied by much laughter and many reminders that, ‘It’s not dangerous. It’s really rather timid!’

This happened in Comfort, Texas, where armadillo encounters are commonplace. If we turn back the clock about 75 years, Comfort was known as the armadillo capital of the world. It was not that they had more armadillos per acre than anywhere else, but just that an enterprising farmer named Charles Apelt had created an international armadillo industry, which he ran from his ranch in Comfort. From curiosity shops to medical research labs, Mr Apelt was the man to contact regarding armadillos.1

Apelt moved from Germany to a farm near Comfort, Texas, in 1887. Encountering his first armadillo, which he described as a ‘moving rock’, Apelt summarily killed the odd little creature. When he came back several hours later to dispose of the carcass, the dead armadillo had curled up in the hot sun, and it gave him an idea. Apelt’s family back in Germany were in the basket making industry, and he instantly saw that the curled armadillo had a basket-like form. The ‘shell’ made a perfect basket when it was cleaned out.

Armoured mammals

This shell-like covering distinguishes the armadillo as one of the real curiosity animals of the western hemisphere. Approximately 20 species of armadillo live in North, South, and Central America, the most common being the nine-banded (referring to the nine ‘bands’ of ‘armour’ encircling the armadillo). Its range extends from Uruguay and northern Argentina all the way into the United States.2 The nine-banded is the only armadillo in North America.

Apelt began selling his armadillo baskets locally as curiosity pieces. He also sent some to his family back in Germany, and it was not long before they began to import and sell them. By the 1920s ‘Apelt’s Armadillo Co.’ was employing over 50 men, using dogs, to actively hunt armadillos in the Texas hills. The armadillo is primarily a nocturnal animal, so the hunts were conducted at night.

When pursued, the armadillo is capable of sprinting rapidly through thick underbrush. This is the first place that the armadillo’s ‘armour’ comes in handy, since it doesn’t snag on branches and brambles as fur or hair would—it is superbly well-suited for its habitat. The armadillo, a mammal, has long been considered ‘reptile-like’ because of this shell-like armour, comprised of overlapping plates of bone. The bony covering is a defence system, although it does not protect the underside of most armadillos. If a dog or other predator ever catches up with it, the armadillo then relies on its powerful burrowing capabilities to quickly dig itself halfway down into the ground, and then hold on with its strong claws. The dog can’t get a firm grip on its back because of the armour, and the hole the armadillo has dug protects its vulnerable underside. (The South American three-banded armadillo can actually roll into a ball for more thorough protection.)3

Despite the difficulties for hunters, Apelt’s armadillo business was booming. His armadillo baskets were being sold in novelty shops from the local San Antonio area to Germany, New Zealand, and Australia. Apelt also got into the business of supplying live armadillos to medical schools for research and experiments.4

Heading north

Incredibly, armadillos were rare in Texas in the 1830s.5,6 Their numbers then began to multiply quickly. The northward expansion of the nine-banded armadillo’s range has surprised many people. At first, naturalists suggested that north Texas had to be the limit of the armadillo’s range. Studies indicated that armadillos could not survive more than about nine days of freezing weather at a time.7

But by the 1950s, the armadillo not only had completed its conquest of Texas (where it is designated as the state animal), but had continued further north, entering Oklahoma and Arkansas.8 By the 1980s the armadillo was reported to have made its way completely through Oklahoma,9 with scattered reports of armadillos in the next state north, Kansas.

The armadillo had some human help in two other colonisations in the 1920s. A soldier in the US Army apparently brought a pair of armadillos with him when he returned home to Florida from a stint of duty in Texas. He released the armadillos into the wild and they, along with a few escapees from a private zoo, began to spread not only throughout Florida, but also into the adjacent state of Georgia. Armadillos also appeared in Mississippi in the 1920s (presumed stowaways in railroad cattle cars from Texas), from where they also spread into Alabama.10

For creationists, the observed rapid spread of the nine-banded armadillo in recent history is a great case study of the dispersal of animals that happened after the Flood, as the earth was repopulated with animals. The geographical spread of some types of animals, as in the case of the armadillo, can happen with astonishing rapidity by both natural means and human assistance.

Problems for evolutionists

Evolutionists say that the fossil ‘record’ of armadillos ‘begins’ in South America11—but such long-age interpretation of fossil-bearing sedimentary rock layers leaves them puzzling over the origin of armadillos. They have ventured some tentative guesses about the ancestry of the armadillo, but not very convincingly. The uniqueness of the backbone of the xenarthran family, a class of animals including armadillos as well as anteaters and sloths, makes it difficult to establish evolutionary relationships beyond the xenarthrans.12

It is very significant to note that the plates of the ‘shell’ (called scutes) were fully formed in their ‘earliest’ find in the fossil ‘record’.13 Evolutionists are disappointed that there is not a developmental ‘history’ of the scutes in the fossils, but this is precisely what creationists would expect—fully formed fossils with no record of evolutionary history. Creationists interpret the fossil-bearing sedimentary layers as a legacy of the global Flood of Noah’s day (or subsequent events). Consequently the ‘earliest’ fossils are no older than around 4,500 years. The Flood wiped out all armadillos that were not aboard the Ark (Genesis 7:21–23), but after the Flood, Noah’s armadillos disembarked and began to multiply again.

But skeptics might ask why armadillos (until their recent spread northwards) were only found in South America? And why no armadillo fossils elsewhere?

In response to the latter question, one only has to point out that the geographical location of fossils doesn’t necessarily match where that animal (or plant) is found living today. For example, hardly any bison fossils have been found in North America, yet we know there were millions of bison roaming around there.

As for the question about the distribution of living armadillos, it’s logical that as animal populations enlarged and spread out from the Ark, carnivore populations (e.g. wolves) would have lagged behind herbivores and insectivores, possibly driving them (e.g. armadillos) further out (all the way to South America). Given that presumed scenario, and that the wolf apparently never made it to South America, then after its demise in North America, it’s hardly surprising that armadillos began to expand (back) into Central and North America.

The 20 species of armadillo living in South and Central America range in size from the small and very unusual pink fairy armadillo (about the size of a guinea pig), to the giant armadillo (the size of a large dog), weighing up to 59 kg (130 lb). The commonest armadillo, the nine-banded, and the second most common, the three-banded, grow to about a half-metre (20 in.) in length.

Evolutionists often misrepresent creationists as believing that God formed all the species exactly as they are now.14 No informed creationist has ever made such a claim. Rather, God formed the animals by kinds,15 a classification that may be defined in terms of hybridization (the ability to interbreed). Of course, even knowing which animals can interbreed now cannot accurately tell us which animals could interbreed several thousand years ago.16 So it is entirely possible that many of the species of armadillos we now have are descended from an original prototype of the armadillo ‘kind.’17 This is not evolution, but just genetic variation within the created kind.

Designed for what it does

The armadillo is perfectly designed for what it does. As a timid insectivore, it has speed and armour to provide a defence of escape rather than fighting. The vertebrae of the armadillo are uniquely designed for strengthening digging power, aiding these insectivores in procuring their meals, and digging their burrows.18 The bony plates allow them to go through underbrush without getting caught. And for creationists, there is no mystery in the fact that all armadillo fossils were found with their scutes (armour plates) fully formed, since that was how God made them in the beginning, and they’ve been reproducing ‘after their kind’ ever since.

The armadillo and leprosy

The armadillo has been very useful in scientific research on leprosy. The leprosy bacterium (Mycobacterium leprae) cannot grow independently, but must grow inside a host’s cells. Attempts to cultivate the leprosy bacterium M. leprae in tissue culture have so far been unsuccessful, so at first researchers had to rely on microscopic M. leprae growths on the footpads of mice for convenient research samples. The nine-banded armadillo was suspected of being an ideal carrier of M. leprae, and research in the 1970s confirmed this.1

The microbe’s optimum temperature (around 30°C, or 86°F) is much lower than the core temperature of the human body (this explains why the effects of leprosy are disfiguring in the serious cases, since surface-level skin tissue has a low temperature).2 The armadillo has a low average body temperature of 33°C (93°F),3 so the bacterium thrives on the armadillo.

Happily for the armadillo, the M. leprae genome has recently been deciphered. So researchers hope to be able to grow the bacterium in a tissue culture.4

References

- Convit, J., and Pinardi, M.E., Leprosy: confirmation in the armadillo, Science 184(4142):1191–1192, 1974.

- Scheepers, A., Correlation of oral surface temperatures and the lesions of leprosy, Int. J. Lepr. 66(2)214–217, 1998.

- Smith, L.L., and Doughty, R.W., The Amazing Armadillo: Geography of a Folk Critter, University of Texas Press, Austin, p. 74, 1984.

- Walgate, R., ‘Massive decay’ in leprosy genome—massive for research too? News from The Scientist, 2(1):20010222-02, 2001.

Re-posted on homepage: 5 April 2017

References and notes

- Smith, L.L., and Doughty, R.W., The Amazing Armadillo: Geography of a Folk Critter, University of Texas Press, Austin, ch. 3, 1984. Return to text.

- Recent range mapping information for the nine-banded armadillo is available at InfoNatura, Birds, mammals, and amphibians of Latin America: Dasypus novemcinctus—nine-banded Armadillo, natureserve.org, accessed April 2006. Return to text.

- Ref. 1, pp. 11–12. Also, Doughty, R.W., personal communication, 15 November 2005. Return to text.

- Ref. 1, pp. 50, 55, 58–59. Return to text.

- Ref. 1, pp. 30–36. Return to text.

- The earliest report of an armadillo in Texas was in 1834: ‘about the size of a muskrat, with a shell and skin resembling in texture those of the alligator, and having wreaths or seams, like those of the rhinoceros, around its body, from the head to the end of the tail. It is a pretty creature, and wonderfully expert at burrowing.’ Lundy, B., quoted in ref. 1, p. 30. Return to text.

- Ref. 1, pp. 26–27. Return to text.

- Ref. 1, p. 36. Return to text.

- Ref. 1, pp. 36–38; 27. It should be noted that although the armadillos have continued to expand, their numbers are much greater in the south. Return to text.

- Ref. 1, pp. 38–41. Return to text.

- Patterson, B., and Pascual, R., The fossil mammal fauna of South America, Quarterly Review of Biology 43(4):422–423, 1968. Return to text.

- See Engelmann, G.F., The phylogeny of the xenarthra, in Montgomery, G.G. (ed.), The Evolution and Ecology of Armadillos, Sloths, and Vermilinguas, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington and London, pp. 51–61, 1985. Return to text.

- Ref. 11, p. 422. Return to text.

- For example, in the first episode of the American PBS television series Evolution. Return to text.

- Genesis 1:21, 24–25. Also see Genesis 6:20, 7:24, 8:19, where the animals are taken into the ark by ‘kinds.’ Return to text.

- For more on the created kinds, see Sarfati, J., Refuting Compromise, ch. 7, Master Books, Arkansas, USA, pp. 230–234, 2004. Also see Wieland, C., Variation, information and the created kind, J. Creation 5(1):42–47, 1991, creation.com/kind. Return to text.

- Hybridization studies would be very interesting to conduct with armadillos, but unfortunately the nine-banded armadillo has proven difficult to breed in captivity. Efforts to breed the three-banded armadillo in zoos have had some success. Bernier, D., telephone interview with the author, Chicago, 15 November 2005. (David Bernier is the studbook keeper and population manager for the Lincoln Park Zoo’s three-banded armadillo research project.) Return to text.

- Xenarthran, Encyclopædia Britannica from Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service, britannica.com, accessed January 2006. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.