Journal of Creation 16(3):27–31, December 2002

Browse our latest digital issue Subscribe

The Tower of Babel account affirmed by linguistics

Secular linguists are puzzled by the existence of twenty or so language families in the world today. The languages within each family (and the people that speak them) have been shown to be genetically related, but few genetic links have been observed between families. This is a problem for secular linguists. If, as they believe, man evolved from an ape-like ancestor, man would at some point have gained the ability to speak. This process of change would actually be superbly dangerous, as they admit. But still, if speech did evolve somewhere, somehow, we would expect to find that all languages are genetically related. They clearly are not. Some have therefore suggested that man evolved speech simultaneously in more than one place. This suggestion is beyond belief, considering the dangers involved in the supposed evolution of speech. So how did the language families come into existence?

Only Genesis provides a credible explanation. It records how God gave the people new languages to speak. Groups speaking the same language moved away together. The languages they spoke then, have slowly evolved into the six thousand-or-so languages we find today, but the distinctions between the groups of languages are still observable, as we shall see.

Determining whether or not languages share a common ancestor is not easy. A Dutch student learning Hindi might not realize that Hindi is related to Dutch. Yet, both languages have been shown to be part of the Indo-European language family. Steel has previously covered in detail the development of the Indo-European languages, clearly refuting claims that this paralleled biological evolution.1 Apparently, all languages in this family have developed from a ‘parent language’, which no longer exists.

This idea was unknown in the late 18th century, until Sir William Jones suggested that Greek, Latin and Sanskrit had independently ‘sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists’.2 He also suggested that other groups of languages, such as the Celtic and Germanic languages, though quite different, might also be related in the same way. Few question his findings today. Comparative and Historical Linguistics have more or less carried on what Jones began. Two centuries have revealed much, and the findings are encouraging for Creationists, who believe the account of the Tower of Babel in Genesis 11 to be a true, historical account of events.

In this essay we shall be looking at some of the evidence for Babel, and examine two rival theories as well. Before we do that, let us have a brief look at the methods involved.

Language classification

The Indo-European language family is not the only language family in the world. There are others, which are more difficult to examine. We have many writings of some European languages, covering more than 2,500 years of development. For many other languages, however, there are no writings at all. That makes the study of their development more complicated.

The traditional way of comparing languages was to compare the history and grammar structures of two languages, while keeping in mind physical and cultural similarities between the tribes. This method was useful in Europe, but it was time-consuming and proved difficult in Africa. Several decades of hard work at the beginning of this century had uncovered only the tip of the iceberg, as far as all languages in Africa were concerned.

A dramatic breakthrough came in the person of Joseph Greenberg in the middle of last century. Greenberg came up with a new method. He collected lists of words from many African languages, and compared them with each other. He noticed clear patterns. Several languages had similar sounding words for similar things, and Greenberg concluded that these languages must therefore be related. His method has become the norm in comparative linguistics.

Greenberg’s method is one of two major ways of classifying languages. Typological classification looks at grammatical structures and classifies languages accordingly. However, there may not be a genetic relationship between languages with a similar typological makeup. Since we are interested in genetic relationship we will now have a brief look at the second method, Genetic Qualification, and consider its findings in relation to our essay question.

Genetic qualification

Core vocabulary

Genetic qualification prefers to use only ‘core vocabulary’, i.e. words which are said to change little over time. The method aims to see how many of these words are similar in different languages, while keeping in mind how words usually change in pronunciation.

The core vocabulary includes, amongst others, words for body parts, numbers, and personal pronouns. When clear patterns of similarities between languages are observed, then those languages are said to be related.

Cognate words

The word ‘patterns’ in the previous paragraph was carefully chosen, because the core vocabulary between related languages is never identical, but similar, or ‘cognate’. Words are cognate when they are shown to be consistent to the pattern of phonetical change that has taken place in the past. For example, the word tahi in Tongan might not look like kai in Hawaiian, even though they both mean ‘sea’. But, if you also compare Tongan tapu to Hawaiian kapu (both meaning ‘forbidden’) and Tongan tanata to Hawaiian kanaka (meaning ‘man’) you begin to see a pattern: Where Tongan has an initial ‘T’ Hawaiian has an initial ‘K’, and one begins to see that the words might be related. They are cognate.3

Common phonetic changes

Deciding which words are cognate and which words are not is never easy. Different scholars have made different judgements when comparing the same lists. There is no general agreement in all cases. There are, however, a few rules to go by, as certain phonetical changes are more likely to occur than others. Stronger sounds, for example, may become weaker.

Equally, words may lose initial or final letters, or merge two consonants into one. These changes are fairly common. The opposites of these examples may also happen, but are less common. Words easily lose sound; they rarely gain it.

Findings after many decades of observation

Comparative linguistics has come a long way since Greenberg began his radical technique. His method has been used extensively across the world, and has led to the systematical genetic categorisation of most languages in the world.4 There is no agreement in detail, but the following groupings, with several variations, are common.5

European and Asian families

The Indo-European family covers most of Europe plus a part of south west Asia. In northern Europe we find the Uralic Family, which includes Finnish and Hungarian. In north-east Asia we find the Chukchi-Kamchatkan family. Central Asia and the rest of northern Asia host the Altaic family, which also contains Turkish. Southern Asia hosts the Sino-Tibetan, Dravidian, Daic and Austroasiatic families. Finally, the Caucasus may host two further families.

Pacific families

The Pacific is host to three or four families. The languages of the Australian Aborigines are usually grouped as one family, as are the languages spoken on mainland Papua. There is no agreement on the treatment of Tasmanian, which is now extinct. The Austronesian family includes languages spoken on Madagascar, the Southern part of the Malaysian Peninsula, the Indonesian Islands, the Philippines, and the Maori languages.

African families

The Afro-Asiatic (Arabic) family is found in North Africa, the Nilo-Saharan languages are spoken in the centre of Africa; the Niger-Kongo family, which includes Swahili, is found in west and east Africa and the Khosian languages are spoken in the south-west of Africa.

American families

The Americas host three major families, with many sub-groupings. The Aleut-Eskimo is found in northern Canada, from the eastern part of Alaska to Greenland. The Na-Dene group is found in north-eastern Canada and Alaska, and also includes some languages spoken in the south west of the United States. Finally, the Amerind family covers the rest of the Americas.

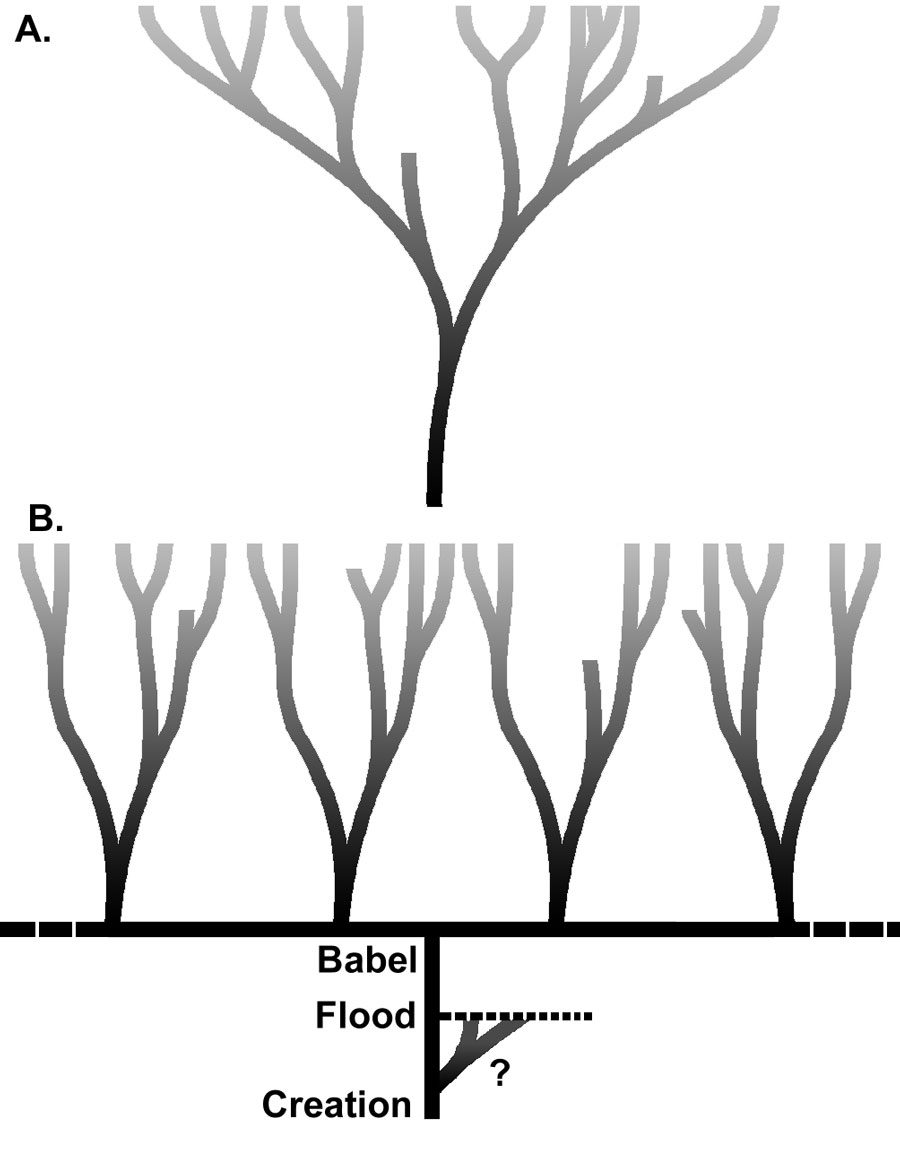

Picture incomplete

In this classification we count some twenty major families. However, this classification is far from complete. Several languages seem unrelated to any other language, and are treated by some as separate families. Moreover, new discoveries are made regularly, which may show two families to be related. This, in turn, may cause two families to merge into one. Ruhlen, for example, found many similarities recently between the isolated language Ket (spoken in Siberia) and some of the Na-Dene languages, which suggests they may be related.6 These discoveries do not surprise all linguists. Some believe that all families ultimately go back to one single language, which came into existence when humans first developed speech. Others argue that human speech developed independently in different places, thus resulting in several language families, while Creationists argue that the Tower of Babel Account in Genesis 11 explains the existence of the variety of families observed today.7 Let us see what evidence there is for or against each side.

Evidence for one single proto language?

‘The ultimate question, is’, says Ruhlen, ‘whether all human languages are genetically related’,8 but the evidence for this is scarce. There are a few words which, he says, are similar in all languages. However, the words he gives in his example do not have the same meaning in every language. The meanings vary from ‘one’ to ‘finger’ and ‘hand’.9 There are similarities between them, but this is not convincing evidence of genetic relationship between language families.

It must be pointed out, though, that we cannot go back too far in time. Core vocabulary is stable, but does change. In some languages this change has been measured for more than 2,000 years. The result shows that 19.5% of the core vocabulary changes every 1,000 years.10 If this is the same for all languages, it means that statistically all words in a language should be replaced within a period of about 10,000 years. That would make any research beyond that period of time impossible. This, in turn, makes it impossible to prove that all language families are ultimately related.

Evidence for the evolution of speech?

Trask shows that humans differ from their ‘closest relatives, the apes’ in that their vocal tracts are much longer and differently shaped, thus making speech possible. However, the shape is also dangerous, as it could lead to choking. ‘The idea is’, says Trask, ‘that speech and language proved to be so beneficial to the species that we became specialised for it even at the cost of losing a number of fellows to death by choking every year.’11 However, Trask remains unsure as to how and when this change occurred.

O’Grady and Dobrovolsky, similarly, despite describing in some detail how the brain processes speech, admit ignorance as to how and when speech developed. ‘We know considerably less about the evolutionary specialisation for non vocal aspects of language … and the interpretation of meaning.’12 Again, there is no evidence to back their view that speech evolved.

It seems clear from their writings that they take the Evolution Theory for granted. Ruhlen admits that ‘scholars supporting monogenesis or the relatability of all languages run the risk of being branded Creationists and of therefore having their work disregarded by colleagues’.9

Evidence pointing to Babel

We have seen that the history of languages cannot be traced back for more than 10,000 years. We have also seen lack of knowledge regarding the evolution of human speech. It seems that there is little evidence to support the view that all languages evolved from one or more proto-languages. There is, however, another explanation for the existence of the language families in the world today. This explanation is found in Genesis.

We will now examine the evidence supporting the Babel account found in Genesis 11. We will focus in particular on three areas where the findings of historical and comparative linguistics back this account.

Language families

We are unsure how many languages spread out from Babel. The Bible teaches that everyone at Babel spoke the same language; it says ‘the whole world had one language and a common speech’. Clearly not enough time had passed for other fully fetched languages to develop since Noah and his family left the Ark, especially since all the people were in one place—though slightly different dialects might have developed in the period between Noah leaving the Ark and the tower of Babel. In any case, the conclusions reached in this essay that Genesis adequately explains the findings of historical and comparative linguistics would be the same. The exact location of Babel is unknown. It is possible that one of the Ziggurats unearthed in modern Iraq is the remains of the infamous tower. As the number of people alive at the time would not have been great, about a dozen or so languages would probably have been plenty.13 Keeping in mind how languages change, we would expect, as Wieland suggests, to find several distinct language families today.

‘ … it should be possible to group [languages] together into “families” like the Indo-European family of languages. But there should be no links between one “family” and another. That is because, in this model, each distinct language family is the offshoot of an original Babel “stem language” which did not arise by chance from a previous ancestral language.’14

The Babel account suggests that several languages came into existence on that day. It is presented as a miraculous intervention by God. It is unlikely to have been acceleration of normal language changes (i.e. they did speak the same language, but dialects began to form) as people in the same area generally speak the same dialect.

We have already seen that at present about twenty language families are being distinguished, with yet some ‘isolated’ languages unaccounted for. There are indications that further research will reveal that some of these families may be related to each other, resulting in fewer families.7

If the percentage of word loss described above is correct, we expect to see many similarities, still, between all languages in each family after only 5,000 years since Babel. However, the absence of any contact between languages in one family, over such a period, could result in greater word loss, so that comparing those languages today would indicate no relation. Also, some languages have a much quicker word loss, for cultural reasons. These languages, therefore, change much quicker.15

The findings of some twenty language families, then, with several ‘isolated’ languages unaccounted for, is consistent with our expectations, as outlined above. Clearly distinguishable families however, continue to puzzle secular linguists, who generally believe languages evolved naturally, as these distinctions are not consistent with the expectations their hypotheses demand.

Timing consistent

Even though he seems convinced that all languages stem from a single Proto Language, Robins talks of a ‘unitary state’ of the Indo-European language family, which is ‘as far as one can at present go by comparative and historical inference’. He adds, ‘Whatever date may be ascribed (and 3,000 BC has been suggested) aeons of linguistic history lie behind it [emphasis mine].’16 However, it seems odd to believe in those ‘aeons of linguistic history’, without any evidence, unless one takes the evolution theory for granted, as he does. The evidence indicates otherwise. We do observe an original language, or at least, traces of it, from which the Indo-European languages have derived. The 3,000 years BC, which Robins mentions, is significant, as such a time span is consistent with the Biblical account.

Moreover, recent findings, as we have seen, suggest that Ket is related to the Na-Dene languages. This suggests that the tribes are related, but that they separated when the American tribes moved from Asia across the Bering Strait into America. Wieland points out that ‘to have such close correlation’s still existing makes little sense if the migrations were as much as 11,000 years ago, as is commonly believed. From the biblical record, they would have been less than some 4,000 years ago’.17 Again, the evidence backs the Genesis account.

Language design and change

‘All languages are something of a ruin’; a quote Crowley attributes to Dutch linguist van der Tuuk. ‘What he meant, was that as a result of changes having taken place, some “residual” forms are often left to suggest what the original state of affairs might have been.’18 Crowley carries on to share how languages can change from sophisticated to simpler versions, and from simpler to more complex systems. He distinguishes between, ‘isolating’, ‘agglutinating’ and ‘inflecting’ languages and shows how languages change in circular patterns.

Isolating languages, he says, are those where every word has only one meaning, i.e. no endings. They tend to become agglutinating when free form grammatical markers, i.e. prepositions, are phonologically reduced to endings or suffixes. Agglutinating languages thus look ‘as if the bits of the language were simply “glued” together to make up larger words’.19 Subsequent morphological reduction make the original grammatical markers unrecognizable, but the endings remain functional. The language has become an inflecting language, in which ‘there are many morphemes included within a single word, but the boundaries between one morpheme and another are not clear.’19 Finally, morphological reduction makes the language lose its ‘cases’ and the language returns to being an isolating language.

In the case of Greek, this change can be seen very clearly in history. Classical Greek was a highly inflected language; it used five cases, as well as Active, Middle and Passive voice. Koine Greek was almost reduced to four cases, and the Middle voice was used rather inconsistently. Modern Greek distinguishes only three cases, but many endings have disappeared. It is a good example of van der Tuuk’s Ruin, as it is slowly becoming an isolated language.

Crowley’s model shows that languages can change from inflecting languages, with ‘endings’, to isolating languages. These may appear to be easier in structure, but are in fact equally complex, as the lack of subtle nuances, which the endings and prefixes often provide, leads to ambiguity.

Crowley does show that isolating languages can change further and pick up complicated case systems after they have lost them. However, this model cannot be used to explain the origin of highly sophisticated language systems like Sanskrit and Greek. History shows that when a language changes, it tends to become more user-friendly. It likes to be flexible. When it has rid itself of cases, it is free to make them up again. However, as these changes are spontaneous, unplanned, and often unnoticed, it seems impossible that a language as sophisticated and regular as the Indo-European ‘parent’ was made up from a simpler form. Language change, as Crowley’s model shows, would be unlikely to produce consistent endings for the whole of the Inflecting Language.20

Steel1 has shown how modern Indo-European languages have reduced the number of noun inflections for different case, gender and number; and different verbs inflection for tense, voice, number and person. He also showed how English has also lost 65–85% of the Old English vocabulary, and many Classical Latin words have also been lost from its descendants, the Romance languages (Spanish, French, Italian, etc.).

Steel1 also pointed out that most of the changes were not random, but the result of intelligence. For example: forming compound words by joining simple words and derivations by adding prefixes and suffixes, modification of meaning, and borrowing words from other languages including calques (a borrowed compound word where each component is translated and then joined). There are also unconscious but definitely non-random changes such as systematic sound shifts, for example those described by Grimm’s Law (which relates many Germanic words to Latin and Greek words).

The fact remains that the Greek/Sanskrit parent was utterly consistent, and highly sophisticated. If chance, then, did not make this Proto Language, where did it get its consistency from? The only credible explanation is found in Genesis 11. It suggests a Designer. In Babel one of the groups was given the sophisticated, and utterly consistent, Proto Indo-European language. Sadly, as people in a fallen world began to use this language, it slowly began to lose some its consistency, as grammatical mistakes became fashionable. Today, some 5,000 years later, some of the languages which descended from it, still have some traces left of the original case system. Some have completely rid themselves of it, and have become isolating languages, while others have made up entirely new case systems, but less consistent and less sophisticated than the original.

The observation of language structure and language change, therefore, is also more consistent with the account of the Tower of Babel than rival theories.

Conclusion

The facts we observe today are consistent with the Tower of Babel account in Genesis 11, but this does not prove the correctness of the account. Since the history of languages cannot be reconstructed beyond 10,000 years, evidence for (and against) alternative views is limited.

However, if we take an objective look at the facts at our disposal we cannot but draw the conclusion that the Bible account has far more going for it than the alternatives, for which there is little, if any, evidence. We therefore wholeheartedly believe that the findings of historical and comparative linguistics have served indeed to affirm the Tower of Babel account recorded in Genesis 11, beyond reasonable doubt. As always, Scripture cannot be ‘proven to be right’ by man’s findings. We believe Scripture is right, as it originates from an infallible God. However, where man’s findings are objectively interpreted, they usually affirm the accounts in Scripture, rather than deny them. This paper has applied the findings of historical and comparative linguistics to the Genesis account, and found that the facts to our disposal are affirmative indeed.

Believing this account, however, requires believing in God, and the denial of the evolution theory, which suggests that all animals, humans, and even human language, arose by chance. For many, this might prove too big a price to pay, despite the evidence.

References

- Steel, A.K., The development of languages is nothing like biological evolution, Journal of Creation 14(2):31–40, 2000. Return to text.

- Cited in: Crowley, T., An Introduction to Historical Linguistics, Oxford University Press, Oxford, p. 24, 1992. Return to text.

- Crowley, Ref. 2, pp. 91ff. Return to text.

- Certain languages, like Basque, seem to have little in common with other languages. They are either not classified, or treated as a separate language family Return to text.

- Ruhlen, M., A guide to the World’s Languages, Edward Arnold, London, 1987. Return to text.

- Ruhlen, M., Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 95:13994–13996, 1998, as cited in: Wieland, C., Siberian Links for Amerindians, Creation 21(3):9, 1999. Return to text.

- Ruhlen, Ref. 5, pp. 257ff. Return to text.

- Ruhlen, Ref. 5, p. 260. Return to text.

- Ruhlen, Ref. 5, p. 261. Return to text.

- Crowley, Ref. 2, p. 169. Return to text.

- Trask, R.L., Language, the Basics, Routledge, London, p. 18, 1999. Return to text.

- O’Grady, M. and Dobrovolsky, M., Contemporary Linguistics, St. Martin’s Press, New York, p. 10, 1989. Return to text.

- Wieland, C., Towering change, Creation 22(1):22–26, citing p. 26, 1999. Return to text.

- Wieland, Ref. 13, p. 26. Return to text.

- Crowley, Ref. 2, pp. 155f. Return to text.

- Robins, R.H., General Linguistics: An Introductory Survey, Longmans, London, p. 229. Return to text.

- Wieland, C., Siberian links for Amerindians, Creation 21(3):9, 1999. Return to text.

- Crowley, Ref. 2, p. 122. Return to text.

- Crowley, Ref. 2, p. 135. Return to text.

- It could possibly make such patterns for an agglutinating language, but not for an inflecting language, as the phonological reduction would not be consistent. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.