100 years of airplanes—but these weren’t the first flying machines!

Christian commitment

The Wright Brothers gained their insights from analyzing the design of living fliers. Their father was a clergyman, and Wilbur planned to follow in his footsteps until he lost most of his teeth in an accident. The brothers professed faith in Christ from their youth, and their Christian character was evident throughout their lives. Their father often related the positive effect that the Bible had made on his sons. 1 Powered flight is yet another advance in science made by Bible-believers who were inspired by God’s design in nature.

Reference

- Lamont, A., The Wright Brothers—pioneers in the skies, Creation 13(4):24–27, 1991. Return to text.

I am pleased to say it was a fellow Yorkshireman, Sir George Cayley, who first achieved heavier-than-air flight, but without a motor. In 1853, he designed the world’s first person-carrying triplane glider. With his somewhat frightened coachman aboard, it successfully flew across his estate. But controlled powered flight is very different.

One hundred years ago, Wilbur and Orville Wright from Dayton, Ohio, took to the skies at the Kill Devil Hills near Kittyhawk in North Carolina at 10:35 am on the cold morning of 17 December 1903.

The first flight lasted 12 seconds and spanned 120 feet. Their fourth and final flight of that day carried Wilbur Wright 852 feet in 59 seconds.

The Wright brothers had achieved the first recorded controlled powered flight by a heavier-than-air machine. However, Richard Pearse, from the South Island of New Zealand, may have achieved powered flight in a heavier-than-air machine in March 1903, but the records are scant compared to the records of the Wright brothers. Furthermore, Pearse agreed that the Wrights deserved the honour of being the first to make a controlled and sustained flight. (They had, for many years, experimented with control by warping the canvas wings to change their camber, along with putting rudder controls on the tail fin.)

Flying machines: intricate design needed

Controlled flight is the secret to the beautiful flight of birds, insects and bats. These creatures have not brought about controlled flight by a series of random chance mutations and natural selection ‘favouring’ survival of creatures with such changes. Flight cannot happen in such a way. All aeronautical engineers know this. Controlled flight requires a balance of main surfaces, coupled often with a tail or extra aerodynamic surfaces that can alter lift and change direction of the flying machine. And none of these give any advantage if there is no control mechanism to alter these surfaces with knowledge and coordinated control—flight is an example of irreducible complexity. That is, all the surfaces and control mechanisms need to be there together to have a controllable machine.

Orville and Wilbur found that out the hard way after numerous accidents in gliders and early powered flight attempts. For controlled flight, there are four fundamental requirements: (1) a correct wing shape to give a lower air pressure on the upper surface; (2) a large enough wing area to support the weight; (3) some means of propulsion or gliding; and (4) extra surfaces, or a means of altering the main surfaces, in order to change direction and speed.

God’s powered fliers came before man’s

Flight occurs in many branches of the living world—birds, insects (flies, bees, wasps, butterflies, moths), mammals such as bats, and the extinct reptiles called pterosaurs.

But each class of creature is anatomically different, with no connection made even by the most ardent evolutionist. A tenuous connection has been attempted between reptiles (dinosaurs) and birds, although birds are warm blooded, which presents a vast hurdle for a reptile ancestry for birds.

Some evolutionists have seriously proposed that there was a ‘pro-avis’ reptile that flapped scales on its ‘arms’ to catch insects, and then its scales changed to feathers to gain airborne advantage over its prey. However, there is no evidence of any ‘pro-avis’ creature in the fossil record. Even the so-called ‘feathered dinosaurs’ from China were nothing of the sort. In some, their ‘feathers’ were merely frayed collagen fibres. Other specimens were flightless birds and not dinosaurs at all.1,2

Furthermore, flight would have needed to evolve independently at least three times! The wings of the three main groups of flying creatures today are substantially different—birds’ wings are made of feathers, insect wings of membranes, lattices of tiny blood vessels or scales, and bat wings use skin spread out over a skeleton. So the evolutionist is faced with not just one impossible hurdle—that some reptiles grew feathers and began to fly—but two further hurdles. Flight evolved again when some rodents (mice? shrews?) developed a skin-like surface over their front legs to become bats. Also, hundreds of millions of years before, some insects had grown very thin scales to become flies, bees and butterflies!

However, according to the Bible, God created all air/flying creatures (Hebrew ôph) on Day 5 of Creation Week, while land creatures were created on Day 6. This is a problem for progressive creationists such as Hugh Ross, who believe in the evolutionary timescale and order of events, because this places land creatures before air creatures. But using the Bible to interpret the fossil record, we realize that the order does not reflect a sequence of ages, but the sequence of burial by Noah’s Flood.2 The more mobile birds avoided the floodwaters longer.

Feathers

A feather is a marvel of lightweight engineering. Though light, it is very wind-resistant due to a clever system of barbs and barbules. Each barb, visible with the naked eye, comes off the main stem. But on either side of the barb are further tiny barbules which can only be seen under a microscope. The two sides of the barb produce different barbules. On one side ridged barbules emerge; on the other side the barbules have hooks. The hooks coming out of one barb connect with ridges reaching in the opposite direction from a neighbouring barb. These work like ‘velcro’, but go one better, since the ridges allow a sliding joint—an ingenious mechanism for keeping the surface flexible and yet intact.4 The next time you see a flight feather on the ground, remember it is a marvel of lightweight flexible aerodynamic engineering. Reptile scales have no hint of such complicated design. The evolutionist Barbara Stahl freely admitted:

Complex design

These images show a delicately preserved fossilized dragonfly wing compared to a living specimen. They appear exactly the same. Likewise, the fossil and modern feather demonstrate that the complex design known in birds’ feathers exists also in the fossil record with no evolution.

‘No fossil structure transitional between scale and feather is known, and recent investigators are unwilling to found a theory on pure speculation.’5

Reptiles lack the genetic information to produce such a unique device as the sliding joint of a feather. The fanciful evolutionary suggestion that feathers resulted by accumulating small ‘advantageous mutations’ to scales leads only to clumsy in-between structures which would harm the creature. Not until all the hook and ridge structure is in place, is there any advantage, even as a vane for catching insects! Unless one invokes some ‘thinking ahead’ planning, there is no way that chance mutations could produce the ‘idea’ of the cross-linking of the barbules to make a connecting lattice. Even if the chance mutation of a ridge/hook occurs in two of the barbules, there is no mechanism for translating this ‘advantage’ to the rest of the structure. This is another classic case of irreducible complexity which is not consistent with slow evolutionary changes, but perfectly consistent with the notion of deliberate design.

But there is more. The sliding joint made by the hooked and ridged barbules needs lubricating oil. Most of us realize that once the barbs of a feather have been separated, it is difficult to make them come back together. The feather becomes easily frayed in the absence of oil, which a bird provides from its preening gland at the base of its spine, using its beak to spread the oil through the feathers. The oil also waterproofs aquatic birds (thus water slides off a duck’s back). Without the oil, and the instinct to apply it, the feathers are useless, so even if a supposed dinosaur got as far as wafting a wing, it would be no use after a few hours!

Bird bones: lightweight and strong

The story does not end there either. A bird can fly only because it also has exceedingly light bones, which is achieved by the bones being hollow. Many birds maintain the skeleton’s strength by cross-members within the hollow bones—such an arrangement began to be used in the middle of this century for aircraft wings and is termed the Warren’s truss arrangement. Large birds such as eagles or vultures would simply break into pieces in mid-air if they had not yet ‘developed’ such cross-members in their bones.

Flapping for flight

Consider the wing-flapping motion of a bird. For powered flight, flapping forces air backwards so the bird is propelled forwards. At the same time the wing has to generate lift. The physics of how it does this is quite complex, depending on the aerofoil shape of the wing and the angle at which the wing meets the air.6

Flapping motion requires a bird to have strong wing muscles, with a forward-facing elbow joint to enable the shortening of the wing during the upward stroke of most species, and in the dive of birds of prey. This, plus the versatility of the swivel joint at the base of the wing and the smooth feathers provide great flexibility in the aerodynamics of the wing. Lift and drag can be balanced with instant adjustments, which in aircraft require comparatively cumbersome changes of flaps and ailerons.

Flying birds: many components must work together

Suppose we have an ‘almost’ bird with all the above structures—viz. feathers, preening gland, hollow bones, direct respiration (see subsection, The bird’s unique lung, below), warm blood, swivel joint and forward-facing elbow joint, but no tail! Controlled flight would still be impossible. Pitch or longitudinal stability (i.e. along the direction of flight) can be achieved only with a tail structure, which most children soon realize when making paper aeroplanes! The tail is essential, but also needs muscles to vary its small, but all-important wing surface—for instance, holding the plumage spread out and downwards when coming in to land. In other words the tail is little use as a static ‘add-on’. It must have the means of altering its shape in flight.

All these mechanisms are controlled by a nervous system connected to the on-board computer in the bird’s brain, preprogrammed to allow a wide envelope of complicated aerodynamic manoeuvres.

Modern airplanes are an example of man’s creativity and intelligence. This should not be surprising, since man was created in the image of God, who was the first to make flying machines. God’s flying machines are far more complicated than man’s—they can even repair and reproduce themselves. So how much more do they declare ‘his eternal power and divine nature’ (Romans 1:20)!

The bird’s unique lung

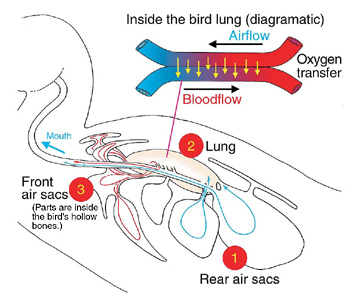

Another fascinating design feature of birds is that they breathe differently from both mammals and reptiles, and even from dinosaurs. 1 The respiratory system of a bird enables oxygen to be fed straight into air sacs which are connected directly to the heart, lungs and stomach. This system keeps air flowing in one direction through special tubes (parabronchi) in the lung, and blood moves through the lung’s blood vessels in the opposite direction for efficient oxygen uptake, 2 an excellent engineering design. 3

This also bypasses the normal mammalian requirement to breathe out carbon dioxide first, before the next intake of oxygen. Human beings breathe about 12 times a minute, whereas small birds can breathe up to about 250 times a minute. This is a perfect system for birds, which use up energy very quickly and so have a high metabolic rate.

A leading evolutionary expert on birds, Dr Alan Feduccia, University of North Carolina, didn’t even attempt to solve this major problem in his book on the evolution of birds. 4 John Ruben, an evolutionary respiratory physiology expert at Oregon State University, said a dinosaur’s ‘bellowslike lungs could not have evolved into the high-performance lungs of modern birds.’ 5 This would apply to the lungs of any reptile, because any hypothetical intermediate forms would not be functional—the earliest stages would have to have a diaphragmatic hernia,1 i.e. a hole in the membranous muscle powering respiration, and natural selection would work against an animal with such a harmful condition.

The bird’s lung must have been created fully functional, or else it wouldn’t have worked at all. Return to main text.

References and notes

- Ruben, J. et al., Lung Structure and Ventilation in Theropod Dinosaurs and Early Birds, Science 278(5341):1267–1270, 14 November 1997. Return to text.

- Schmidt-Nielsen, K., How Birds Breathe, Scientific American, pp. 72–79, December 1971. Return to text.

- Engineers make much use of this principle of counter-current exchange, which is common in living organisms as well—see Scholander, P.F., The Wonderful Net, Scientific American, pp. 96–107, April 1957. Return to text.

- Feduccia, A., The Origin and Evolution of Birds, 2nd ed., Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1999. However, this book shows that the usual dinosaur-to-bird dogma has many holes. Return to text.

- Rubens, J., quoted in Gibbons, A., Lung Fossils Suggest Dinos Breathed in Cold Blood, Science 278(5341):1229–1230, 14 November 1997. Return to text.

Evolutionists admit that scale-to-feather idea is flawed

Some leading feather experts have admitted that creationists were right to point out the futility of scales evolving into feathers. 1 But, unwilling to admit that the problem is with evolution itself, they have proposed another idea. They described it as ‘evo-devo’:

‘Our developmental theory proposes that feathers evolved through a series of transitional stages, each marked by a developmental novelty, a new mechanism of growth.’

However, any evidence for ‘developmental novelty’ is better explained as the creation of information in birds that is not present in any reptiles. In fact, feathers develop under the control of two genes: one which encourages cell proliferation and the other which regulates this proliferation and promotes cell differentiation (i.e. into specialized types), and these genes operate in precise sequence. This is an extra layer of complexity. And the researchers still admit there is a problem explaining how a loose downy feather could evolve into the rigid feather with its elaborate system of hooks and ridges. 2

References and notes

- Prum, R. and Brush, A., Which came first, the feather or the bird? Scientific American 288(3):60–69, March 2003. Return to text.

- Matthews, M., Scientific American admits creationists hit a sore spot: need for a ‘new paradigm’ in bird evolution, 13 March 2003. Return to text.

References and notes

- Sarfati, J., Refuting Evolution, Master Books, Arkansas, USA; CMI, Brisbane, Australia, ch. 4, 1999. Return to text.

- Q&A: Did birds really evolve from dinosaurs? Return to text.

- McIntosh, A. et al., Flood models: the need for an integrated approach, J. Creation 14(1):52–59, 2000. Return to text.

- Bergman, J., The evolution of feathers: a major problem for Darwinism, J. Creation 17(1):33–41, 2003. Return to text.

- Stahl, B., Vertebrate History: Problems in Evolution, McGraw-Hill, New York, p. 349, 1974. Return to text.

- Anderson, D. and Eberhardt, S., Understanding Flight, McGraw-Hill, 2001; A Physical Description of Flight, aa.washington.edu. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.