Ligers and wholphins? What next?

Crazy mixed-up animals … what do they tell us? They seem to defy man-made classification systems—but what about the created ‘kinds’ in Genesis?

If we can cross-breed a zebra and a horse (to produce a ‘zorse’), a lion and a tiger (a liger or tigon), or a false killer whale and a dolphin (a wholphin), what does this tell us about the original kinds of animals that God created?

The Bible tells us in Genesis chapter 1 that God created plants to produce seed ‘after their kind’ (vv. 11, 12). God also created the animals to reproduce ‘after their kind’ (vv. 20, 24, 25). ‘After their/its kind’ is repeated ten times in Genesis 1, giving emphasis to the principle. And we take it for granted. When we plant a tomato seed, we don’t expect to see a geranium pop up out of the ground. Nor do we expect that our dog will give birth to kittens or that Aunt Betty, who is expecting, will bring home a chimpanzee baby from the hospital! Our everyday experience confirms the truth of the Bible that things produce offspring true to their kind.

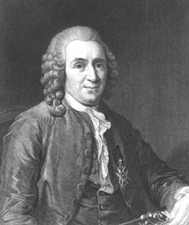

But what is a created ‘kind’? And what organisms today represent the kinds God created in the beginning? The creationist scientist, Carolus Linnaeus (1707–1778), the founder of the science of taxonomy,1 tried to determine the created kinds. He defined a ‘species’ as a group of organisms that could interbreed among themselves, but not with another group, akin to the Genesis concept. ( See aside below.)

Finding the created kinds

From Genesis 1, the ability to produce offspring, i.e. to breed with one another, defines the original created kinds. Linnaeus recognised this, but named many species2 without any breeding experiments, on the basis of such things as flower characteristics. In his mature years he did extensive hybridization (cross-breeding) experiments and realised that his ‘species’ concept was too narrow for the species to be considered as created kinds; he thought that the genus perhaps corresponded better with the created kind.3,4

The Created Cat Kind

Even today, creationists are often misrepresented as believing that God created all the species we have today, just like they are today, in the beginning. This is called ‘fixity of species’. The Bible does not teach this. Nevertheless, university professors often show students that a new ‘species’ has arisen in ferment flies, for example, and then claim that this disproves the Genesis account of creation. Darwin made this very mistake when he studied the finches and tortoises on the Galapagos islands. (He also erred in assuming that creation implied that each organism was made where it is now found; but from the Bible it is clear that today’s land-dwelling vertebrates migrated to their present locations after the Flood.)

If two animals or two plants can hybridize (at least enough to produce a truly fertilized egg), then they must belong to (i.e. have descended from) the same original created kind. If the hybridizing species are from different genera in a family, it suggests that the whole family might have come from the one created kind. If the genera are in different families within an order, it suggests that maybe the whole order may have derived from the original created kind.

On the other hand, if two species will not hybridize, it does not necessarily prove that they are not originally from the same kind. We all know of couples who cannot have children, but this does not mean they are separate species!

In the case of three species, A, B and C, if A and B can each hybridize with C, then it suggests that all three are of the same created kind—whether or not A and B can hybridize with each other. Breeding barriers can arise through such things as mutations. For example, two forms of ferment flies (Drosophila) produced offspring that could not breed with the parent species.5 That is, they were a new biological ‘species’. This was due to a slight chromosomal rearrangement, not any new genetic information. The new ‘species’ was indistinguishable from the parents and obviously the same kind as the parents, since it came from them.

Following are some examples of hybrids that show that the created kind is often at a higher level than the species, or even the genus, named by taxonomists.

Mules, zeedonks and zorses

Crossing a male ass (donkey—Equus asinus) and a horse (Equus caballus) produces a mule (the reverse is called a hinny). Hybrids between zebras and horses (zorse) and zebras and donkeys (zedonk, zonkey, zebrass) also readily occur.

Some creationists have reasoned that because these hybrids are sterile, the horse, ass and zebra must be separate created kinds. However, not only does this go beyond the biblical text, it is overwhelmingly likely that horses, asses and zebras (six species of Equus) are the descendants of the one created kind which left the Ark. Hybridization itself suggests this, not whether the offspring are fertile or not. Infertility in offspring can be due to rearrangements of chromosomes in the different species—changes such that the various species have the same DNA information but the chromosomes of the different species no longer match up properly to allow the offspring to be fertile. Such (non-evolutionary) changes within a kind can cause sterility in hybrids.

Ligers

A male African lion (Panthera leo) and a female tiger (Panthera tigris) can mate to produce a liger. The reverse cross produces a tigon. Such crossing does not normally happen in the wild because most lions live in Africa and most tigers live in Asia. Also, lions and tigers just don’t mix; they are enemies in the wild. However, the Institute of Greatly Endangered and Rare Species, Myrtle Beach, South Carolina (USA), raised a lion and a tigress together. Arthur, the lion, and Ayla, the tigress, became good friends and bred to produce Samson and Sudan, two huge male ligers. Samson stands 3.7 m (12 feet) tall on his hind legs, weighs 500 kg (1,100 lbs) and can run at 80 km/hr (50 mph).

Lions and tigers belong to the same genus, Panthera, along with the jaguar, leopard and snow leopard, in the subfamily Felinae. This subfamily also contains the genus Felis, which includes the mountain lion and numerous species of smaller cats, including the domestic cat. The cheetah, genus Acinonyx, belongs to a different subfamily.6 Thus the genera Panthera, Felis and Acinonyx may represent descendants of three original created cat kinds, or maybe two: Panthera-Felis and Acinonyx, or even one cat kind. The extinct sabre-tooth tiger may have been a different created kind (see diagram above; Note added in support, October 2020: a study of the DNA of an extinct sabre-toothed cat found that it was quite different to all other cats; doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.09.051).

The Panthera cats lack a hyoid bone at the back of the tongue, compared to Felis. Acinonyx has the hyoid, but lacks the ability to retract its claws. So the differences between the cats could have arisen through loss of genetic information due to mutations (loss of the bone; loss of claw retraction). Note that this has nothing to do with molecules-to-man evolution, which requires the addition of new information, not loss of information (which is to be expected in a fallen world as things tend to ‘fall apart’).

Kekaimalu the wholphin

In 1985, Hawaii’s Sea Life Park reported the birth of a baby from the mating of a male false killer whale (Pseudorca crassidens) and a female bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus).7 The birth surprised the park staff, as the parents are rather different in appearance. Here we have a hybrid between different genera in the same family, Delphinidae (dolphins and killer whales).8 Since the offspring in this case are fertile (Kekaimalu has since given birth to a baby wholphin), these two genera are really, by definition, a single polytypic biological species.2 Other genera in the group are much more alike than the two that produced the offspring in Hawaii, which suggests that the 12 living genera might have all descended from the original created kind.

Rama the cama

Veterinarians in the United Arab Emirates successfully cross-bred a camel and a llama. The ‘cama’, named ‘Rama’, has the cloven hooves of a llama and the short ears and tail of a camel. The scientists hope to combine the best qualities of both into the one animal—the superior fleece and calmer temperament of the llama with the larger size of the camel.

Genae the hybrid snake

‘Genae’ (pictured right) resulted from a cross between an albino corn snake (Elaphe guttata) and an albino king snake (Lampropeltis triangulum) in a reptile park in California.9 Apparently, this particular intergeneric hybrid is fertile. Genae is almost four years old and already 1.4 m (4½ ft) long. The parent snakes belong to the same snake family, Colubridae; the success of this hybrid suggests that the many species and genera of snakes in this family today could have all originally come from the same created kind.

Other hybrids

With the cattle kind, seven species of the genus Bos hybridize, but so also does the North American buffalo, Bison bison, with Bos, to produce a ‘cattalo’. Here the whole family of cattle-type creatures, Bovidae, probably came from an original created cattle kind which was on the Ark.10

Plant breeders have bred some agriculturally important plants by hybridizing different species and even genera. For example, triticale, a grain crop, came from a cross of wheat (Triticum) and rye (Secale), another fertile hybrid between genera.

During my years as a research scientist for the government in Australia, I helped create a hybrid of the delicious fruit species lychee (Litchi chinensis) and longan (Dimocarpus longana), which both belong to the same family.11 I also studied the hybrids of six species of the custard apple family, Annonaceae. Each of these two family groupings, recognised by botanists today, probably represents the original created kinds.

God created all kinds, or basic types, of creatures and plants with the ability to produce variety in their offspring. These varieties come from recombinations of the existing genetic information created in the beginning, through the marvellous reproductive method created by God. Since the Fall (Genesis 3), some variations also occurred through degenerative changes caused by mutations (e.g. loss of wing size in the cormorants of the Galápagos Islands).

The variations allow for the descendants of the created kinds to adapt to different environments and ‘fill the earth’, as God commanded. If genera represent the created kinds, then Noah took less than 20,000 land animals on the Ark; far fewer if kinds occasionally gave rise to families. From these kinds came many ‘daughter species’, which generally each have less information (and are thus more specialized) than the parent population on the Ark. Properly understood, adaptation by natural selection (which gets rid of information) does not involve the addition of new complex DNA information. Thus, students should not be taught that it demonstrates ‘evolution happening’, as if it showed the process by which fish could eventually turn into people.

Understanding what God has told us in Genesis provides a sound foundation for thinking about the classification of living things, as Linnaeus found, and how the great diversity we see today has come about.

A ‘geep’? No—a ‘chimera’

Despite the fact that the ‘geep’ has both sheep and goat in its parentage, and shares the characteristics of both species, it is usually not a true hybrid. It is usually a ‘chimera’, formed by mixing the (fertilized) embryo cells of two different species.

The DNA in each adult cell (including sex cells) is thus either fully sheep or fully goat—hence there are patches of either thin white goat fur or thick sheep’s wool. Thus also, any offspring will be either all sheep or all goat. This artificial manipulation is very different from the situation where two animals of the same kind (but different species) mate producing live offspring. However, there are rare examples of true hybrids between sheep and goats.

Linnaeus and the classification system

Linnaeus established the two-part naming system of genus and species. For example, he called wheat Triticum aestivum, which means in Latin, ‘summer wheat’. Such ‘scientific’ names are normally italicised, with the genus beginning with a capital. When used in scientific works, the names are followed by the abbreviated name of the scientist responsible for the name. When ‘L.’ follows a name, this shows that Linnaeus first applied the name. For example, the name for maize or ‘corn’ is Zea mays L. Linnaeus named many plants and animals.

There can be one or many species in a genus, so genus is a higher level of classification. Linnaeus also developed the idea of grouping genera (plural of genus) within higher groupings he called orders, and the orders within classes. Linnaeus opposed the pre-Darwin evolutionary ideas of his day, pointing out that life was not a continuum, or a ‘great chain of being’, an ancient pagan Greek idea. He could classify things, usually into neat groups, because of the lack of transitional forms.

Later, other levels of classification were added so that today we have species, genus, family, order, class, phylum and kingdom. Sometimes other levels are added, such as subfamily and subphylum.

The world’s only Wholphin … false killer whale/dolphin cross

False killer whales (pseudorcas) and bottlenose dolphins are each from a different genus. Man-made classification systems were thrown into confusion when these two creatures mated and produced a live offspring (see main text).

This suggests that all killer whales and dolphins, which are all in the same family, are the one created kind.

This wholphin’s size, shape and colour are right in between those of her parents. She has 66 teeth—an ‘average’ between pseudorcas (44 teeth) and bottlenose dolphins (88).

Kekaimalu has since mated with a dolphin to produce a live baby.

References and notes

- The study of the naming and classification of organisms. Return to text.

- ‘Biological species’ is often used today to refer to a group of organisms that can interbreed to produce fertile offspring. It does not always correlate with the taxonomic ‘species’. Note that the kinds would originally have met the criterion for each being a separate biological species, since they did not interbreed with any other kind. Return to text.

- In Latin, ‘genus’ conveys the meaning of origin, or ‘kind’, whereas ‘species’ means outward appearance (The Oxford Latin Minidictionary, 1995). Return to text.

- Creationist biologists today often combine the Hebrew words bara (create) and min (kind) to call the created kind a baramin. Return to text.

- Marsh, Frank L., Variation and Fixity in Nature, Pacific Press, CA, USA, p. 75, 1976. Return to text.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica 98 CD. Other authorities call the Panthera genus Leo, so that the lion is then Leo leo. Return to text.

- Keene Rees, Waimanalo Hapa Girl Makes 10! Waimanalo News, May 1995, hotspots.hawaii.coml, March 1, 2000. Return to text.

- The New Encyclopaedia Britannica 23:434, 1992. Return to text.

- Genae belongs to David Jolly, M.S. (USA). Genae was bred at a reptile park at Bakersfield. Corn snakes are one of the most popular pet snakes in North America, and snake fanciers have bred all sorts of colour variations, which are catalogued at members.aol.com/, March 22, 2000. Return to text.

- See Wieland, C., Recreating the extinct Aurochs? Creation 14(2):25–28, 1992. Return to text.

- McConchie, C.A., Batten, D.J. and Vithanage, V., Intergeneric hybridization between litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.) and longan (Dimocarpus longan Lour.), Annals of Botany 74:111–118, 1994. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.