Blurring the line between abortion and infanticide?

2 July 2008

When the Roe v. Wade decision was delivered, the reality that a baby was being killed during abortion was less clear to many people—it was common to think that what was being removed was ‘a blob’ or ‘a clump of cells’. But most who would be in favor of abortion would at least draw the line at birth—once the baby is outside the womb, nearly everyone agrees that he or she is entitled to the full protection of the law, regardless of what route the baby took to get there. But some think that there is one time a fully-born baby does not have the right to life—when he or she was born as a result of a botched abortion.

Peter Singer: infanticide-supporting ‘bioethicist’

Peter Singer

Peter Singer (1946–) is probably the most well-known bioethicist who, though he is too humane to eat a hamburger and advocates giving rights to great apes, has no qualms about infanticide. To him, an unborn child only acquires ‘moral significance’ at around 20 weeks’ gestation, when the baby is able to feel pain. But ‘[e]ven when the fetus does develop a capacity to feel pain—probably in the last third of the pregnancy—it still does not have the self-awareness of a chimpanzee, or even a dog’, and so he gives greater ‘moral significance’ to the chimpanzee and dog than to the unborn child.1

He readily admits that the unborn child is fully human, but argues that the humanity of the unborn child does not obligate society to preserve that life. In Rethinking Life and Death, Singer takes the view that ‘newborn-infants, especially if unwanted, are not yet full members of the moral community’, and proposes a 28-day period in which the infant might be killed before being granted full human rights.2 In a 2007 column, Singer seems to reverse his position on the acceptability of infanticide in most cases, but makes it clear that it is not because a child acquires a new ‘moral significance’ once it exits the womb, but because ‘the criminal law needs clear dividing lines and, in normal circumstances, birth is the best we have.’3 However, he argued in another article that, due to the high rate of disability in very premature infants, doctors should not treat babies born before 26 weeks of gestation if the parents of such a child decide not to treat their infant.4 Singer asserts: ‘killing a disabled infant is not morally equivalent to killing a person. Very often it is not wrong at all.’5 Indeed, this sort of thought has been the basis of wrongful birth lawsuits by parents who claim that their disabled children should not have been born.

Situation ethics

Singer’s bizarre views on human life may belong on the lunatic fringe, but they are fairly mainstream in what passes for ‘bioethics’. Singer’s views stem from a philosophy known as utilitarianism, in which the stated goal is to maximize pleasure and minimize pain for the most people possible. So the ‘right’ decision in any given situation is that which results in the most pleasure and the least pain for the greatest number of people. The use of utilitarian ethics was popularized by Joseph Fletcher (1905–1991), an apostate Episcopalian minister who became an atheist. He is best known for creating ‘situation ethics’, and was hailed ‘the patriarch of bioethics’ by bioethicist and former Roman Catholic priest Albert R. Johsen (1931–).6 Situation ethics can be summed in the book transcript of a debate between Fletcher and the Christian apologist and lawyer John Warwick Montgomery (1931–):

‘ … Whether we ought to follow a moral principle or not would always depend upon the situation. … In some situations unmarried love could be infinitely more moral than married unlove. Lying could be more Christian than telling the truth … stealing could be better than respecting private property … no action is good or right of itself. It depends on whether it hurts or helps people. … There are no normative moral principles whatsoever which are intrinsically valid or universally obliging. We may not absolutize the norms of human conduct. … Love is the highest good and the first-order value, the primary consideration to which in every act … we should be prepared to sidetrack or subordinate other value considerations of right and wrong.’7

Montgomery scored a powerful point with the audience when he showed that situation ethicists shouldn’t be trusted under their own belief system, because they could happily deceive you if the situation were right.

The Christian viewpoint is that moral absolutes are real (see the articles under Are there such things as moral absolutes?). Where there is a conflict, the resolution is not situational but depends on the biblical hierarchy of absolutes: duty to God > duty to man > duty to property; obeying God's laws > obeying the government. This system is called graded absolutism, where there are exemptions rather than exceptions to moral absolutes, i.e. the duty to obey the higher absolute exempts one from the duty to obey the lower one.8

Personhood

Fletcher also popularized the distinction between ‘human being’ and ‘person’ that is central to Singer’s ethics.9 He proposed a formula to determine whether an individual qualified as a ‘person’, with requirements such as ‘minimum intelligence’, ‘self awareness’, ‘memory’, and ‘communication’.10 Singer’s denial of the unborn child’s personhood is central to his justification for abortion, as he freely admits that the unborn child is alive and human.11 Tom Beauchamp goes as far as to say, ‘Many humans lack properties of personhood or are less than full persons, they are thereby rendered equal or inferior in moral standing to some nonhumans.’12

It’s notable that while the pro-aborts like to claim that science is on their side, they have to resort to fuzzy concepts like ‘personhood’. Conversely, pro-lifers generally point out the genuinely scientific criteria for when the individual’s life begins. And they are on a sound basis. With improved 4D ultrasound technology, it is now possible to view a child in the womb with clarity, and in real time, that leaves no question that he is a distinct living being. Genetic evidence supports this even more strongly:

‘The task force finds that the new recombinant DNA technologies indisputably prove that the unborn child is a whole human being from the moment of fertilization, that all abortions terminate the life of a human being, and that the unborn child is a separate human patient under the care of modern medicine.’13

So the pro-abortion camp changed the definition of ‘person’ from ‘living member of the human species’ to a nebulous definition that could be twisted around to fit their ends (one notices that a bioethicist never seems to think that he himself is not a person worthy of protection under the law). Indeed, as will be shown, a child may fall short of the definition of ‘person’ even after birth.

Evolutionary basis for denial of sanctity of innocent14 human life

Of course, this view of human life is antithetical to the biblical teaching of mankind as beings created in the image of God, and therefore possessing great intrinsic worth. Bioethicist Daniel Callahan argued that ‘[t]he first thing that … bioethics had to do … was to push religion aside.’15 Euthanasia advocate Dan Brock, Harvard University Program in Ethics and Health, argued:

‘This rights view of the wrongness of killing is not, of course, universally shared. Many people’s moral views on the wrongness of killing have their origins in religious views that human life comes from God and cannot be justifiably destroyed or taken away, either by the person whose life it is or by another. But in a pluralistic society like our own, with a strong commitment to freedom of religion, public policy should not be grounded in religious beliefs which many in society reject.’16

In Australia, Philip Nitschke (1947–), Founder of the pro-euthanasia organisation EXIT International, said much the same thing:

‘Many people I meet and argue with believe that human life is sacred. I do not. … If you believe that your body belongs to God and that to cut short a life is a crime against God then you will clearly not agree with my thoughts on this issue.’

‘I do not mind people holding these beliefs and suffering as much as they wish as they die. For them, … if that is their belief they are welcome to it, but I strongly object to having those views shoved down my neck. I want my belief—that human life is not sacred—accorded the same respect.’17

Of course, the bioethicists would like one to overlook the fact that they believe public policy should be grounded in their own atheistic religious beliefs which most in society reject.

Singer openly derides those who claim that human life is intrinsically valuable:

‘[S]ome opponents of abortion respond that the fetus, unlike the dog or chimpanzee, is made in the image of God, or has an immortal soul. They thereby acknowledge religion is the driving force behind their opposition. But there is no evidence for these religious claims, and in a society in which we keep the state and religion separate, we should not use them as a basis for the criminal law, which applies to people with different religious beliefs, or to those with none at all.’18

However, all law stems from some group’s perception of morality; why should Singer’s view of morality be the basis for law simply because it is godless? In light of the fact that most of the atrocities of the 20th century were committed under atheistic regimes, one might think that a religious aspect in ethics is a good thing.

In Roe v. Wade, the infamous 1973 US Supreme Court decision that overturned individual states’ bans on all types of abortion, unborn infants were declared to not be ‘persons’ with the right to life under the Constitution, based on ignorance of when precisely life begins. But the justices did manage to find a ‘right’ to abortion in the Constitution that no one had ever noticed before, or as widely cited legal scholar John Ely (1938–2003) put it:

‘the Court had simply manufactured a constitutional right out of whole cloth and used it to superimpose its own view of wise social policy on those of the legislatures.’19

‘Unwelcome’ side-effect of abortion: infants who survive!

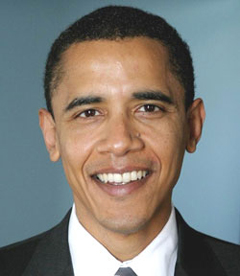

Barack Obama

The Born Alive Infant Protection Act (BAIPA) at the national level, and various bills like it in state legislatures, was introduced in response to reports that some victims of botched abortion, who were born alive, were being left to die. Jill Stanek was a nurse who testified about this practice, having seen infants shelved in dirty utility rooms to die. The BAIPA guaranteed infants born under such circumstances the same right to treatment as other prematurely born children, whether or not the parents wanted the child to be treated. The bill passed the Senate unanimously, with even the most pro-abortion senators agreeing that once a child was born, the mother’s so-called ‘right to choose’ ended. In 2002, BAIPA was signed into law at the national level. However, in the Illinois senate, a state version of the law failed to pass repeatedly, thanks in large part to then-State Senator Barack Obama (1961–). The Illinois BAIPA only passed after Obama left the State Senate. Stanek reports that when she testified before a committee of which Obama was a member:

‘Obama articulately worried that legislation protecting live aborted babies might infringe on women's rights or abortionists' rights. Obama's clinical discourse, his lack of mercy, shocked me. I was naive back then. Obama voted against the measure, twice. It ultimately failed. In 2003, as chairman of the next Senate committee to which BAIPA was sent, Obama stopped it from even getting a hearing, shelving it to die much like babies were still being shelved to die in Illinois hospitals and abortion clinics.’20

At the national level, Obama has proved to be one of the most pro-abortion senators, going so far as to vote against a law that would require an abortionist performing an abortion on a minor transported across state lines to notify at least one parent. He opposed the US Supreme Court decision upholding the ban on partial-birth abortion, the gruesome procedure in which a late-term baby’s body is delivered leaving only the head in the birth canal, when the abortionist sucks the baby’s brains out then delivers the dead baby now that the head has been suitably shrunk.21

Obama v Christian ethics

It is hard to justify such extremism as support for ‘women’s rights’, especially when, in many places in the world, abortion targets unborn girls over boys. Obama said regarding his own daughters that ‘if they make a mistake, I don’t want them punished with a baby.’22 But the Bible regards children as blessings to be thankful for, not as nuisances (Psalm 127:4–5). Many stories in Scripture revolve around women who are heartbroken over their inability to have children and are blessed finally with sons of their own (Sarah, Rebekah, Hannah, Elizabeth), and the Bible speaks clearly about the humanity of the unborn (Genesis 25:21–22, Psalm 139:13–16, Jeremiah 1:5, Luke 1:41–44).

Obama may not openly or even consciously support the utilitarian ethic that Singer and most other bioethicists embrace, but his position on infanticide, devaluing certain human life as unworthy of life, has its roots in evolutionary utilitarian thought and defining personhood separately from humanity. But it should be no surprise—Obama is an ardent evolutionist, saying, ‘Evolution is more grounded in my experience than angels’.

However, at least the atheistic bioethicists like Singer and Fletcher are being consistent—one may call their worldview evil and abominable, but not illogical. But Obama claims to be a Christian while embracing positions that are inherently antithetical to any Christian ethic. As inexcusable as it is to claim to be too humane to eat meat while advocating baby butchery, it is worse to be pro-infanticide while claiming to worship the God in whose image the babies are made.

Editorial note:

CMI does not engage in partisan politics; we are, though, very much concerned with the effects on society of evolutionary thinking. Thus, when a candidate for the world's most powerful political position (regardless of party affiliation), not only espouses evolution but shows clearly the outcome of it on their thinking on such biblically serious matters, it is very much within our ministry mandate.

Feedback on this article

CMI supporter Scott Gillis from the USA says:I just read this feature article on the website by Lita Sanders. The article was intriguing and prompted me to read other articles she has written for CMI. I would like to commend her writing style, topic choice, and logic. Thank you.

References

- Singer, P., Abortion: the dividing lines, Herald Sun, 25 August 2007; <www.news.com.au/heraldsun/story/0,21985,22304219-5000117,00.html>. Return to text.

- Singer, P., Rethinking Life and Death: The Collapse of Our Traditional Ethics, pp. 130, 217. New York: Prometheus Books, 1995; cited in: Flynn, D. Intellectual Morons: How Ideology Makes Smart People Fall for Stupid Ideas, p. 74. New York: Crown Forum, 2004. Return to text.

- Singer, ref. 1. Return to text.

- Singer, P., Early births fade to grey, The Australian, 3 January 2007; <www.utilitarian.net/singer/by/20070103.htm>. Return to text.

- Singer, P., Taking life: Humans, <www.utilitarian.net/singer/by/1993----.htm>. Return to text.

- Jonsen, A.R., “‘O Brave New World’: Rationality in reproduction; in: Thomasma, D.C. and Kushner, T. (eds.), Birth to Death: Science and Bioethics, p. 50, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1996; cited in Smith, Ref. 9; online. Return to text.

- Montgomery and Fletcher, Situation Ethics, Canadian Institute for Law, Theology & Public Policy, Inc., 1999. Return to text.

- See Geisler, Norman, Christian Ethics: Options and Issues, Baker Academic, 1989. Return to text.

- Smith, Wesley J., Culture of Death: the Assault On Medical Ethics In America, p. 11, San Francisco: Encounter Books, 2000. Return to text.

- Smith, ref 9, p. 12. Return to text.

- Singer, ref. 1. Return to text.

- Smith, ref. 9, p. 16. Return to text.

- New Scientist 189(2543):8–9, 18 March 2006. Return to text.

- ‘Innocent’ is here used in the original sense of the Latin in-nocens = ‘not harming’, as it is used in law, rather than meaning ‘sinless’. Return to text.

- Callahan, D., Why America Accepted Bioethics, The Hastings Center Report 23, 1993 Return to text.

- Brock, D.W., Life and Death: Philosophical Essays in Biomedical Ethics, p. 213, Cambridge University press, 1993. Return to text.

- Lopez, Kathryn Jean, Euthanasia sets sail: An interview with Philip Nitschke, the other Dr Death , National Review Online, 5 June 2001. Return to text.

- Singer, ref. 1. Return to text.

- Ely, John Hart, The Wages of Crying Wolf: A Comment on Roe v. Wade, The Yale Law Journal 82:920–949, 1973. Return to text.

- Stanek, Jill, Why Jesus would not vote for Barack Obama, World Net Daily, 19 July 2006. For further documentation refuting claims by Obama supporters that he is not an infanticide supporter, see Hudson, Deal, With abortion backing, is it fair to say Barack Obama supports infanticide?, 8 August 2008. Return to text.

- Henthoff, Nat, Infanticide Candidate for President, World Net Daily, 30 April 2008. Hentoff is a self-described atheist. Return to text.

- Brody, David, Obama Says He Doesn’t Want His Daughters Punished with a Baby, 31 March 2008. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.