The genealogies of Jesus

This is the pre-publication version which was subsequently revised to appear in Creation 37(1):22–25.

Matthew’s and Luke’s genealogies have differences that are apparent at even a cursory glance. Even some Bible scholars have given up on a satisfactory solution. For instance, Nolland says in his Matthew commentary:

Various attempts have been made at harmonisation, none of which is better than speculative. Given the contradictions in OT and other ancient genealogies and the varied functions of genealogies, it is probably best to let each genealogy make its own contribution to an understanding of the significance of Jesus.1

The implication is that it doesn’t matter whether Jesus is actually descended from who he is said to be descended from, because we are primarily meant to draw theological significance from it. But because Scripture presents a God who acts in history, the historical and the theological are inseparably connected—if these aren’t Jesus’ real genealogies, then they don’t really tell us anything about Him. Worse, the Bible would be lying.

Fortunately, we don’t have to give up on a solution. While any harmonization will involve some ‘guesswork’ on our part (because we don’t have all the data still available to us today), we can come up with a biblically consistent scenario that gives a reasonable explanation for some of the apparent differences in the genealogies.

Two genealogies?

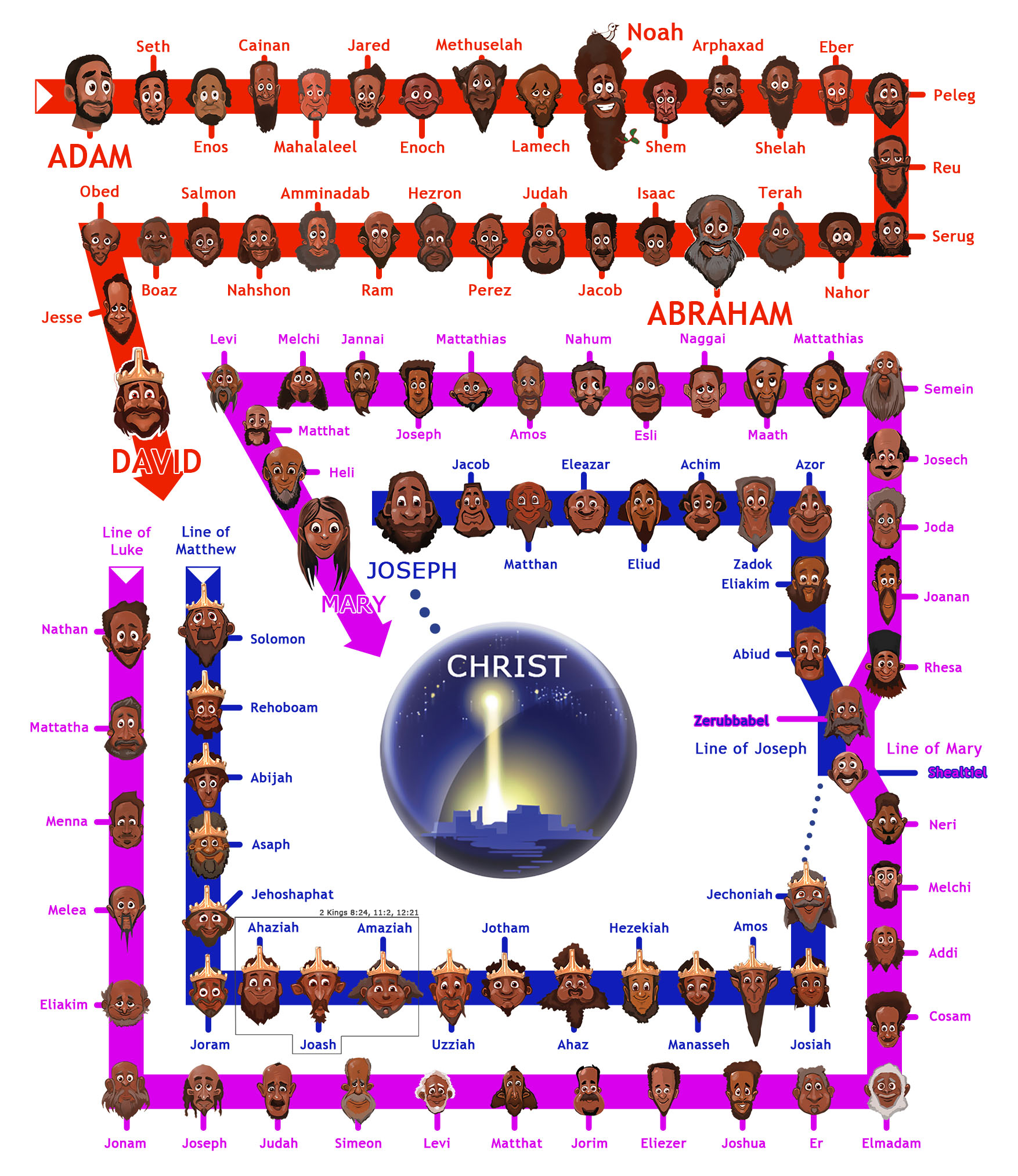

The first question would be “How can someone have two genealogies?” Matthew’s genealogy traces the line through Joseph back to David through his son Solomon; Luke’s genealogy goes back through David’s son Nathan all the way back to Adam. But between David and Joseph, the lines only converge at Shealtiel and Zerubbabel, only to promptly split again! How do we explain this?

First, it’s important to note that genealogies traced all sorts of adoptive relationships, as well as biological ones. And these adoptive relationships were just as real and legally binding as biological relationships, and inheritance was one important reason why someone might be adopted as an heir. The descendants of the house of David would have a particular important inherited title to ensure a succession for—the kingship.

Grammatically, the Greek is clear—both genealogies are genealogies of Joseph. The Greek of Matthew 1:16 reads: Ἰακὼβ δὲ ἐγέννησεν τόν Ἰωσὴφ τὸν ἄνδρα Μαρίας, ἐξ ἧς ἐγεννήθη Ἰησοῦς ὁ λεγόμενος Χριστός (Iacōb de egennēsen ton Iōsēph ton andra Marias, ex hēs egennēthē Iēsous ho legomenos Christos). Translated, it reads, “And Jacob begat Joseph the husband of Mary, of whom2 was born Jesus who is called the Christ.” So Jacob is Joseph’s father—it’s his genealogy. Luke 3:23 reads: Καὶ αὐτος ἦν Ἰησοῦς ἀρχόμενος ὡσεὶ ἐτῶν τριάκοντα, ὢν υἱος, ὡς ἐνομίζετο, Ἰωσἠφ τοῦ Ἡλὶ (Kai autos hēn Iēsous archomenos hōsei etōn triakonta, ōn huios, hōs enomizeto, Iōsēph tou Hēli). Translated, it reads, “And Jesus was around thirty years old when he began [his ministry], being the son, as was supposed, of Joseph, [son] of Heli. Luke is very careful here to note that Jesus was thought to be the son of Joseph (of course, the reader who has just gone through Luke’s birth narrative would know that Jesus had no human father), but when it comes to Joseph’s parentage, it is very straightforward: “Joseph son of Heli”, and then the lineage is traced back through Heli’s ancestors.

There are good reasons to assume that both are valid genealogies. In the first century, it may have still been a matter of public record, because for access to the Temple to worship, a Jew had to be able to prove his ancestry. But why are Matthew and Luke using different genealogies? Because they are writing with different goals in mind. Matthew is trying to convince his Jewish audience that Jesus is the Son of David, the Messiah they’ve been waiting for. Therefore a legal ancestry showing the line of descent (even though it has since been lost) would have carried a lot of weight when it was first written. Luke on the other hand is a Gentile writing to Gentiles—so showing Jesus’ common ancestry from Adam would be an important part of emphasizing that He is the Savior for all humanity.

But wait—how can Luke prove Jesus’ humanity by tracing Joseph’s lineage back to Adam? Because although grammatically, it is Joseph’s genealogy, it is probably also Mary’s genealogy as well. If Heli had only daughters, Joseph could have become Heli’s heir (the ‘son of Heli’) by adoption, especially if Joseph became his son-in-law.

Thus Heli would be Jesus’ maternal grandfather—meaning that Luke really traces Jesus’ genetic ancestry back to Adam. This is very important for the biblical teaching that Jesus is our Kinsman-Redeemer (Isaiah 59:20), who died for fellow humans (Hebrews 2:14), who share his common ancestry from one man (as Luke would later record from Paul in Acts 17:26).

While this solution is speculative (as any solution would be, since the Bible doesn’t tell us specifically), I think this does justice to Luke’s emphasis on Jesus’ common humanity with us going back to Adam.

Incidentally, Luke 1:32 seems to give independent support for Mary being a descendant of David. That’s because the angel Gabriel announced that her Son would be a descendant of David. But Mary asked only how she, a virgin, could have a child, not how he would come from David, meaning that the latter part was presupposed because she is from that line.

Why is Matthew’s genealogy ‘too short’?

A cursory comparison of the genealogies from David to Joseph show that Matthew has far fewer names than Luke in the genealogy. Particularly descending from Zerubbabel, there are not nearly enough names in Matthew for the 500-year period that is represented between Zerubbabel and Jesus. But Matthew is not interested in giving a full genealogy here (unlike the chronogenealogies in Genesis)—he is only interested in establishing Jesus’ claim to the throne, and he gives enough of the genealogy to do so.

Shealtiel and Zerubbabel

The other ‘problem’ in the genealogies is that Shealtiel and Zerubbabel are present in both, but with different ancestors and descendants. Matthew says Shealtiel is the son of Jeconiah, but Luke says that he is the son of Neri. There are two solutions which are equally possible. The first is that these are different people. It wouldn’t be unheard of for the same sequence of names to pop up, especially if they weren’t uncommon names during that time period.

But there is another solution which is also attractive, which also has to do with an adoptive relationship. In 2 Kings 20, Hezekiah showed the Babylonian envoys all the treasure of Israel, and Isaiah tells Hezekiah that all the treasure will one day be taken away to Babylon. In addition, some of Hezekiah’s descendants will also be taken and made into eunuchs (2 Kings 20:16–19). It is likely that this happened to Jeconiah when he was taken away to Babylon. If this is the case, he may have adopted Shealtiel son of Neri in order to pass on the right to the throne. And in this scenario, both Mary and Joseph would be descended from Zerubbabel.

What about 1 Chronicles 3?

1 Chronicles 3 gives the family tree of Shealtiel and Zerubbabel, and none of their descendants have the names that are in either Luke’s or Matthew’s genealogies. The simplest explanation is to say that the genealogies in 1 Chronicles, while accurate, are not exhaustive, and didn’t include the descendants named in the Matthew and Luke genealogies.

Why is this important?

A lot of people find genealogies the most boring part of the Bible and even wonder why God would inspire the addition of long lists of names! This is a fairly recent attitude though, and even today, the genealogies are very important to some cultures (read, for instance, about how the Binumarien people realized that Jesus was a real person only when they heard His genealogy). As Christians, we believe that God acts within history to reveal Himself to us, and that He became incarnate in history to save us by His perfect life and sacrificial death and resurrection. Matthew’s genealogy gives weight to Jesus’ claim to be the Son of David, and the son of Abraham—the basis of Paul’s teaching that Jesus is Abraham’s unique Seed (Galatians 3:16). Luke’s genealogy shows how He can be “the Last Adam” because he comes from “the first man, Adam” (1 Corinthians 15:45)—thus the Savior of all humanity, both Jew and Gentile. But they can only do this if they are true genealogies.

Re-featured on homepage: 22 December 2019

References

- Nolland, J. The Gospel of Matthew: A commentary on the Greek text, p. 70, Grand Rapids, Mich.; Carlisle: W.B. Eerdmans; Paternoster Press, 2005. Return to text.

- The Greek word here is feminine, so a ‘dynamic equivalence’ translation might say, “ … Joseph the husband of Mary, the mother of Jesus who is called the Christ”, or some other construction which makes the feminine in the Greek plain. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.