Journal of Creation 15(1):53–57, April 2001

Browse our latest digital issue Subscribe

Disclaimer: How biblical chronology relates to archaeological periods in the ancient Near East (e.g., Paleolithic, Chalcolithic, Early Bronze Age, Iron Age, etc.) is a complex subject. For many years, Creation Ministries International (CMI) has published a range of views by various authors in its publications (CREATION.com, Journal of Creation, Creation magazine, etc.). These views do not necessarily agree with the present views of CMI’s writers on this topic, but remain available online as they form part of CMI’s historical archives of its publications. For key articles about this subject see our Archaeology Q&Ahaeology Q&A.

Searching for Moses

Summary

By the traditional chronology of Egyptian history the 18th dynasty ruled from about 1550 to 1320 BC. According to Bible chronology the Exodus occurred about 1446 BC. But there is no evidence from 18th dynasty Egyptian records of a major disaster such as would have resulted from the 10 devastating plagues that fell on Egypt, or of the destruction of the Egyptian army during this period. Nor is there archaeological evidence for an invasion of Palestine under Joshua during this period.

The solution to this problem is a recognition that the chronology of Egypt needs to be reduced by centuries, bringing the 12th dynasty down to the time of Moses and the Exodus. When this is done there is found abundant evidence for the presence of large numbers of Semitic slaves at the time of Moses, the devastation of Egypt and the sudden departure of these slaves.

A reduction of the chronology of Egypt would also be reflected in the interpretation of the archaeological ages in Israel. There is little evidence for an invasion of Palestine at the end of the Late Bronze Period. But at the end of the Early Bronze Period there is evidence of Jericho’s fallen walls and the arrival of a new people with a new culture who should be identified as the invading Israelites under Joshua.

The challenge to the Bible

The 18 December 1995 edition of Time magazine had on the front cover a picture of Moses holding a slab of stone, on which are the Ten Commandments, with the question splashed across the centre of the page asking, ‘IS THE BIBLE FACT OR FICTION?’.

The article claims that there are

‘parts of the Old Testament where the evidence is contradictory or still absent, including slavery in Egypt, the existence of Moses, the Exodus and Joshua’s military conquest of the Holy Land … . Kathleen Kenyon, who excavated at Jericho for six years, found no evidence of destruction at that time’ (p. 54).

In fact, she claims that Jericho was uninhabited in 1400 BC, the Biblical date for the Exodus.

‘When the material is analysed in the light of our present knowledge, it becomes clear that there is a complete gap both on the tell and in the tombs between c.1580 BC and c.1400 BC.’1

The expression ‘at that time’ is extremely significant. The fact is that there is plenty of evidence for slavery in Egypt, the existence of Moses, the Exodus and Joshua’s military conquest of the Holy Land. At Jericho, Professor Garstang uncovered toppled walls and a thick layer of ash all over the tell which denoted a fire that had been deliberately lit.

‘The outer wall suffered most, its remains falling down the slope … . Traces of intense fire are plain to see, including reddened masses of brick, cracked stones, charred timbers and ashes. Houses alongside the wall were found burnt to the ground, their roofs fallen upon the domestic pottery within.’2

But it was not at the time archaeologists had allocated to the event.

‘It had been believed in the earlier excavations that the defensive walls of the Late Bronze Age town had been discovered, and that they had been destroyed by earthquake and fire. It became clear in the course of the recent excavations that these walls had been mistakenly identified. They actually belonged to the Early Bronze Age.’3

From the information revealed in 1 Kings 6:1, the date of the Exodus can be calculated. It says, ‘And it came to pass in the four hundred and eightieth year after the children of Israel had come out of the land of Egypt, in the fourth year of Solomon’s reign over Israel, in the month Ziv, which is the second month, that he began to build the house of the LORD’.

Most historians agree that Solomon ascended the throne about 970 BC.4 His 4th year would be 966 BC, and 480 years before that would be about 1446 BC. According to the traditional dates accepted by most archaeologists, that would be during the rule of the 18th dynasty of Egypt.

A proposed revision of Egyptian chronology

It is true that there is no evidence for Moses, the ten plagues that fell upon Egypt or the exodus ‘at that time’. But there are a number of scholars who claim that a gross error in chronology has been made in calculating the dates of Egyptian history and that they should be reduced by centuries.5 Such a re-dating could bring the 12th dynasty down to the time of Moses, and there is plenty of circumstantial evidence in that dynasty to support the Biblical records.

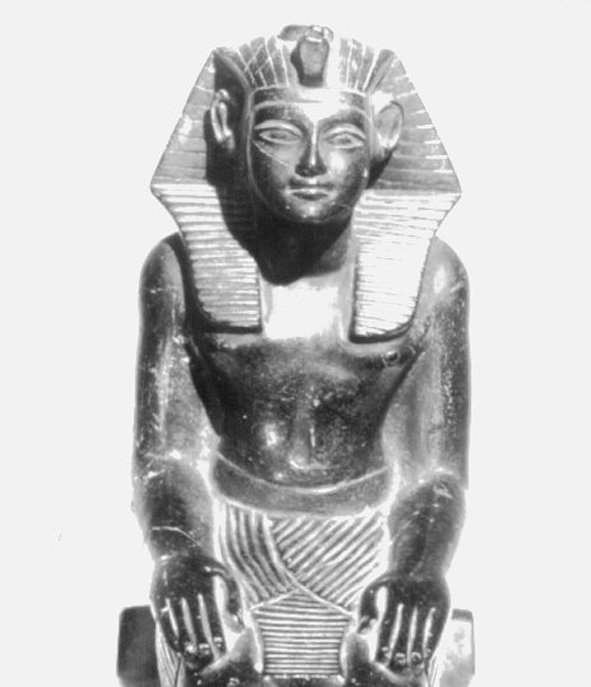

One of the last kings of the 12th dynasty was Sesostris III. His statues depict him as a cruel tyrant quite capable of inflicting harsh slavery on his subjects. His son was Amenemhet III, who seems to have been an equally disagreeable character. He probably ruled for 46 years, and Moses would have been born near the beginning of his reign.

Amenemhet III may have had one son, known as Amenemhet IV, who was an enigmatic character who may have followed his father or may have been a co-regent with him. If the latter, Amenemhet IV could well have been Moses. Amenemhet IV mysteriously disappeared off the scene before the death of Amenemhet III.

Amenemhet III had a daughter whose name was Sobekneferu. It is known that she had no children.6 If she was the daughter of Pharaoh who came down to the river to bathe, it is easy to understand why she was there. It was not because she had no bathroom in her palace. She would have been down there taking a ceremonial ablution and praying to the river god Hapi, who was also the god of fertility. Having no children she would have needed such a god, and when she found the beautiful baby Moses there she would have considered it an answer to her prayers (Exodus 2:5–6).

But when Moses came of age he identified himself with the people of Israel and was obliged to flee from Egypt. This left a vacuum on the throne, and when Amenemhet III died there was no male successor. Sobekneferu ascended the throne and ruled for 8 years as a Pharaoh, but when she died the dynasty died and was succeeded by the 13th dynasty.

The Israelite slaves

For the past 15 years I have been promoting a revised chronology for Egypt.7 This results in identifying the Semitic slaves, who were employed in building the pyramids of the 12th dynasty at Kahun in the Faiyyum, as the Israelite slaves referred to in the book of Exodus. Fifteen years ago I was regarded as being out of touch with archaeological reality, but time has changed all that.

Of course, Dr Immanuel Velikovsky proposed the same revision before I did,8 and so did Dr Donoville Courville,9 but they were written off as irrelevant because they were not archaeologists. Since then, recognized archaeological scholars have joined the chorus of revision.

In 1991, Peter James published his book Centuries of Darkness, claiming that the chronology of Egypt should be reduced by 250 years.10 James was a reputable scholar, and his book carried a preface by Professor Colin Renfrew of Cambridge University recognizing that ‘a chronological revolution is on its way’ (p. XVI), claiming that ‘history will have to be rewritten’ (p. XIV). In 1995, David Rohl published A Test of Time, in which he claimed that the chronology of Egypt should be reduced by 350 years.11 All this meant that the end of the 12th dynasty of Egypt would be dated to the 15th century BC, which would be about the time of the Biblical Exodus, and the slaves known to have lived at Kahun and laboured on the building of the 12th dynasty pyramids were the Israelite slaves.

Professor Bryant Wood, from the Associates for Biblical Research, has also concluded that the Semitic slaves who lived at Kahun were indeed the Israelites.12 He reaches his conclusion from a different perspective but the end result is the same. He concludes that the period of 430 years13,14 mentioned in Exodus 12:40 was not the total period of time from Abraham to the Exodus, as seemingly implied in Galatians 3:17, but was the actual period of the Israelite presence in Egypt. This assumption would likewise place the Israelite slaves in the 12th dynasty

The evidence very well fits the Biblical record which says,

‘There arose a new king over Egypt who did not know Joseph. And he said to his people, "Look, the people of the children of Israel are more and mightier than we; come, let us deal wisely with them, lest they multiply and it happen in the event of war, that they join our enemies and fight against us, and so go up out of the land." Therefore they set taskmasters over them to afflict them with their burdens’ (Exodus 1:8–11).

Sir Flinders Petrie excavated the city of Kahun in the Faiyyum and Dr Rosalie David wrote a book about his excavations in which she said,

‘It is apparent that the Asiatics were present in the town in some numbers, and this may have reflected the situation elsewhere in Egypt … . Their exact homeland in Syria or Palestine cannot be determined … . The reason for their presence in Egypt remains unclear.’15

Neither Rosalie David nor Flinders Petrie could identify these Semitic slaves with the Israelites because they held to the traditional chronology which placed the Biblical event centuries later than the 12th dynasty.

There was another interesting discovery Petrie made. ‘Larger wooden boxes, probably used originally to store clothing and other possessions, were discovered underneath the floors of many houses at Kahun. They contained babies, sometimes buried two or three to a box, and aged only a few months at death.’16

There is a Biblical explanation for this. Pharaoh had ordered the Hebrew midwives, ‘When you do the duties of a midwife for the Hebrew women, and see them on the birth stools, if it is a son, then you shall kill him’ (Exodus 1:16). The midwives ignored this command so ‘Pharaoh commanded all his people saying, "Every son who is born you shall cast into the river … " ’ (verse 22). Many grieving mothers must have had their babies snatched from their arms and killed. They apparently buried them in boxes beneath the floors of their houses.17

Another striking feature of Petrie’s discoveries was the fact that these slaves suddenly disappeared off the scene. Rosalie David wrote:

‘It is apparent that the completion of the king’s pyramid was not the reason why Kahun’s inhabitants eventually deserted the town, abandoning their tools and other possessions in the shops and houses.’18

‘There are different opinions of how this first period of occupation at Kahun drew to a close … . The quantity, range and type of articles of everyday use which were left behind in the houses may indeed suggest that the departure was sudden and unpremeditated.’19

The departure was sudden and unpremeditated! Nothing could better fit the Biblical record. ‘And it came to pass at the end of the four hundred and thirty years—on that very same day—it came to pass that all the armies of the LORD went out from the land of Egypt’ (Exodus 12:41).

The ten plagues on Egypt

Pharaoh had yielded to Moses’ demands to allow his slaves to leave because of the ten devastating plagues that fell on Egypt (Exodus 7–12). The waters of the sacred River Nile were turned to blood, herds and flocks were smitten with pestilence, lightning set combustible material on fire, hail flattened the crops and struck the fruit trees, and locusts blanketed the country and consumed what might have been left of plant life. The economy of Egypt would have been so shattered that there should be some record of such a national catastrophe–and there is.

In the Leiden Museum in Holland is a papyrus written in a later period, but most scholars recognize it as being a copy of a papyrus from an earlier dynasty. It could have been from the 13th dynasty describing the conditions that prevailed after the plagues had struck. It reads,

‘Nay, but the heart is violent. Plague stalks through the land and blood is everywhere … . Nay, but the river is blood. Does a man drink from it? As a human he rejects it. He thirsts for water … . Nay, but gates, columns and walls are consumed with fire … . Nay but men are few. He that lays his brother in the ground is everywhere … . Nay but the son of the high-born man is no longer to be recognized … . The stranger people from outside are come into Egypt … . Nay, but corn has perished everywhere. People are stripped of clothing, perfume and oil. Everyone says "there is no more". The storehouse is bare … . It has come to this. The king has been taken away by poor men.’20

The Pharaoh of the Exodus

There are records of slavery during the reigns of the last rulers of the 12th Dynasty—Sesostris III, Amenemhet III and Sobekneferu (some include an obscure figure known as Amenemhet IV before Sobekneferu). With the death of Sobekneferu the 12th dynasty came to an end as she had no children born to her. Moses, the adopted heir, had fled to Midian.

A period of instability followed the demise of the 12th dynasty. Fourteen kings followed each other in rapid succession, the earlier ones probably ruling in the Delta before the 12th dynasty ended. Kings of the 13th dynasty had already started to rule in the north-east delta and, when the 12th dynasty came to an end, they filled the vacuum and took over as the 13th dynasty. (The idea of dynasties was not an Egyptian idea at the time. It was a later invention of Manetho, the Egyptian priest of the 3rd century BC who left a record of the history of Egypt and divided the kings into dynasties.)

The elevation to rulership over all Egypt by these kings resulted in fierce contention among themselves, resulting in a rapid succession of rulers and more or less anarchy in the country. This only settled down when Neferhotep I took the throne and restored some stability, ruling for 11 years.

I identify Khasekemre-Neferhotep I as the pharaoh from whom Moses demanded Israel’s release. I do so because Petrie found scarabs21 of former kings at Kahun. But the latest scarab he found there was of Neferhotep, who was apparently the pharaoh ruling when the Israelite slaves suddenly left Kahun and fled from Egypt in the Exodus. According to Manetho, he was the last king to rule before the Hyksos occupied Egypt ‘without a battle’. Without a battle? Where was the Egyptian army? It was at the bottom of the Red Sea Exodus 14:28). Khasekemre-Neferhotep I was probably the pharaoh of the Exodus. His mummy has never been found.

In his lecture, Professor Wood associated the name Rameses mentioned in Genesis 47:11 and Exodus 1:11, >12:37 with the Egyptian word ‘RW3TY’, meaning ‘Door of two roads’. He connects it with Stratum d/222 of the new population centre at Tell el-Daba (Avaris, the Capital of the Hyksos), a site which is being excavated by the Austrian archaeologist Manfred Bietak. According to Bietak this stratum has definite evidence for a Canaanite element. It is Stratum d/2 which Wood connects with the Israelites in Egypt.12

Those who identify Rameses II as the pharaoh of the Exodus cite these verses which include the name ‘Rameses’ as evidence to support their identification. But if Rameses was the Pharaoh of the Exodus, his body should be at the bottom of the Red Sea, not in the Cairo Museum where it is today. Wood’s argument dispels the necessity of linking the name Rameses with the Biblical references.

Conclusion

There is plenty evidence for Israelite slavery in Egypt—the sudden disappearance of these slaves, the devastation of Egypt by the ten plagues, the destruction of the Egyptian army—if we look for it at the right time, and time is a vital element in the interpretation of ancient history.

According to the Biblical records, the Exodus occurred 480 years before Solomon laid the foundations of his temple at Jerusalem (1 Kings 6:1). This would place the Exodus about 1446 BC. God’s covenant with Abraham was 430 years earlier (Exodus 12:40, Galatians 3:16, 17) about 1850 BC. From the ages of his predecessors back to Noah, given in Genesis 12 and 13, it can be calculated that the great universal Flood occurred 427 years earlier, about 2302 BC. But according to most authorities on Egyptian chronology the pyramids were built about 1550 BC, and the first dynasty of Egypt ruled about 3100 BC.23

Thus, there is a conflict between Egyptian chronology as generally interpreted and the Biblical records. Neither the first dynasty of Egypt nor the pyramids could have existed before the Flood. If the Bible is historically reliable, as I believe it is, then there must be a mistake in the usual interpretation of Egyptian chronology which needs to be reduced by centuries.

The issue is clear. An acceptance of the present chronological interpretation of Egyptian history, and a rejection of the Biblical chronology, opens the door to skepticism of the rest of the early Biblical records, including the record of the Creation of the world in six days. But if Egyptian chronology can be shown to be flawed, a major obstacle to the acceptance of the Bible records is removed, and the Genesis history stands justified.

References

- Kenyon, K., Archaeology on the Holy Land, Praeger, New York, p. 198, 1964. Return to text.

- Garstang, J., The Story of Jericho, Marshall, Morgan and Scott, London-Edinburgh, p. 136, 1948. Return to text.

- Kenyon, Ref. 1, p. 210. Return to text.

- Mazar, A., Archaeology and the Land of the Bible, Doubleday, New York, p. 369, 1992; Ben-Tor, A., The Archaeology of Ancient Israel, Yale University Press, p. 304, 1994. Return to text.

- James, P. et al., Centuries of Darkness: A Challenge to the Conventional Chronology of the Old World Archaeology, Rutgers University Press, p. 318, 1991; Rohl, D., A Test of Time, Century Ltd, London, p. 143, 1995. Return to text.

- Edwards, I.E.S. et al., The Cambridge Ancient History, Vol. II, part I, Cambridge University Press, p. 43, 1975; David, R., Ancient Egypt, Harper Collins, p. 20, 1988. Return to text.

- Diggings, Vol. 1, No. 3, p. 2, March 1985. Return to text.

- Velikovsky, I., Ages in Chaos, Doubleday, New York, 1952. Return to text.

- Courville, D.A., The Exodus Problem and its Ramifications, Challenge Books, Loma Linda, 1971. Return to text.

- James, Ref. 5, p. 318. Return to text.

- Rohl, Ref. 5, p. 143. Return to text.

- Wood, B., New evidence for Israel in Egypt, Newsletter of the Horn Archaeological Museum, p. 3, Winter–Spring 1999. Return to text.

- There are two main schools of thought on the 430 years of Exodus 12:40. One regards the period as commencing with the entrance of Israel into Egypt or the beginning of slavery, and the other commencing with the covenant with Abraham. As translated in the KJV, the Exodus 12:40 text seems to suggest the entrance of Israel into Egypt, but I consider the Hebrew in Exodus can be translated to support either view. I prefer to build on Galatians 3:17, which seems to place the period as beginning with the covenant with Abraham. Based on the ages of the patriarchs involved, I would consider it 215 years from the covenant with Abraham till Jacob entered Egypt and 215 years in Egypt. It is not possible to determine the years spent in slavery but, based on the pharaohs involved, I would think about 100 years. Return to text.

- See also: Beechick, R., Sojourn of the Jews; Williams, P., Reply to Beechick, Letters to the editor, TJ15(1):60–61, 2001. Return to text.

- David, A.R., The Pyramid Builders of Ancient Egypt: A Modern Investigation of Pharaoh’s Workforce, Guild Publishing, London, p. 191, 1996. Return to text.

- David, Ref. 15, Plate 16. Return to text.

- If the sex of the babies could be determined to be all or mostly male, that would harmonise with Pharaoh’s edict to kill all the male babies. When Dr Rosalie David visited Australia two years ago, I asked her if the sex of the babies found by Petrie was known. She replied that unfortunately Petrie had only sent three skeletons to European museums and they have all been lost. None of them can be traced. Petrie buried the remainder of the skeletons in a sand dune, but no one knows which sand dune as he left no record of it. Return to text.

- David, Ref. 15, p. 195. Return to text.

- David, Ref. 15, p. 199. Return to text.

- Erman, A., Ipuwer Papyrus, Leiden Museum, quoted from The Ancient Egyptians, a source book of their writings, Harper and Row, New York, pp. 94–101, 1966. Return to text.

- The term scarab in archaeological reports refers to seals used for sealing documents though they were often used as ornaments. In either case, they were made of stone, metal or even pottery, with the shape of the scarab beetle on top and the name and title of the king engraved underneath, so when it was pressed down on the soft clay it left his seal impression. Return to text.

- After archaeologists have completed their reports they identify the strata or layers of occupation from the bottom up, so that the lowest layer may be early bronze, the next up middle bronze, the next up late bronze and the top layers iron age or later. But when they first start digging they cannot know what lies beneath, so they number the strata from the top down numbering them 1, 2, 3 etc. These are likely to be later subdivided with letters, so d/2 would be the second layer down and the 4th (d) subdivision of that layer or stratum. Return to text.

- Gardiner, Sir A., Egypt of the Pharaohs: An Introduction, Oxford University Press, pp. 430, 434, 1964. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.