DNA: marvellous messages or mostly mess?

2003 is the 50th anniversary of the discovery of the double helix structure of DNA. Its discoverers, James Watson, Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins, won the Nobel Prize for Physiology and Medicine in 1962 for their discovery. [2011 update: this online version has been updated with animations and links to further amazing discoveries about the multiple codes in DNA.]

The amazing design and complexity of living things provides strong evidence for a Creator. We know from the Bible that God rested from (i.e. finished) His creative work after Day 6 (Genesis 2:2–3) and now sustains His creation (Col. 1:16–17, Hebrews 1:3). So how do complex living creatures arise today?

God’s information technology

One aspect of this sustenance is that God has programmed the ‘recipe’ for all these structures on the famous double-helix molecule DNA.1 This recipe has an enormous information content, which is transmitted one generation to the next, so that living things reproduce ‘after their kinds’ (Genesis 1, 10 times). Leading atheistic evolutionist Richard Dawkins admits:

‘[T]here is enough information capacity in a single human cell to store the Encyclopaedia Britannica, all 30 volumes of it, three or four times over.’2

Just as the Britannica had intelligent writers to produce its information, so it is reasonable and even scientific to believe that the information in the living world likewise had an original compositor/sender.3 There is no known non-intelligent cause that has ever been observed to generate even a small portion of the literally encyclopedic information required for life.4

The genetic code (see ‘The programs of life’ below) is not an outcome of raw chemistry, but of elaborate decoding machinery in the ribosome. Remarkably, this decoding machinery is itself encoded in the DNA, and the noted philosopher of science Sir Karl Popper pointed out:

‘Thus the code can not be translated except by using certain products of its translation. This constitutes a baffling circle; a really vicious circle, it seems, for any attempt to form a model or theory of the genesis of the genetic code.’5,6

The unity of life

Many evolutionists claim that the DNA code is universal, and that this is proof of a common ancestor. But this is false—there are exceptions, some known since the 1970s. An example is Paramecium, where a few of the 64 (4³ or 4×4×4) possible codons code for different amino acids. More examples are being found constantly.1 Also, some organisms code for one or two extra amino acids beyond the main 20 types.2 But if one organism evolved into another with a different code, all the messages already encoded would be scrambled, just as written messages would be jumbled if typewriter keys were switched. This is a huge problem for the evolution of one code into another.

Also, in our cells we have ‘power plants’ called mitochondria, with their own genes. It turns out that they have a slightly different genetic code, too.

Certainly most of the code is universal, but this is best explained by common design—one Creator. Of all the millions of genetic codes possible, ours, or something almost like it, is optimal for protecting against errors.3 But the created exceptions thwart attempts to explain the organisms by common-ancestry evolution.

References and notes

- The genetic codes, National Institutes of Health, 29 August 2002.

- Certain Archaea and eubacteria code for 21st or 22nd amino acids, selenocysteine and pyrrolysine—see Atkins, J.F. and Gesteland, R., The 22nd amino acid, Science 296(5572):1409–10, 24 May 2002; commentary on technical papers on pp. 1459–62 and 1462–66.

- Knight, J., Top translator, New Scientist 158(2130):15, 18 April 1998. Natural selection cannot explain this code optimality, since there is no way to replace the first functional code with a ‘better’ one without destroying functionality.

So, such a system must be fully in place before it could work at all, a property called irreducible complexity. This means that it is impossible to be built by natural selection working on small changes.

DNA is by far the most compact information storage system in the universe. Even the simplest known living organism has 482 protein-coding genes. This is a total of 580,000 ‘letters,’7—humans have three billion in every nucleus. (See ‘The programs of life’, for an explanation of the DNA ‘letters.’)

The amount of information that could be stored in a pinhead’s volume of DNA is equivalent to a pile of paperback books 500 times as high as the distance from Earth to the moon, each with a different, yet specific content.8 Putting it another way, while we think that our new 40 gigabyte hard drives are advanced technology, a pinhead of DNA could hold 100 million times more information.

The ‘letters’ of DNA have another vital property due to their structure, which allows information to be transmitted: A pairs only with T, and C only with G, due to the chemical structures of the bases—the pair is like a rung or step on a spiral staircase. This means that the two strands of the double helix can be separated, and new strands can be formed that copy the information exactly. The new strand carries the same information as the old one, but instead of being like a photocopy, it is in a sense like a photographic negative. The copying is far more precise than pure chemistry could manage—only about 1 mistake in 10 billion copyings, because there is editing (proof-reading and error-checking) machinery, again encoded in the DNA. But how would the information for editing machinery be transmitted accurately before the machinery was in place? Lest it be argued that the accuracy could be achieved stepwise through selection, note that a high degree of accuracy is needed to prevent ‘error catastrophe’—the accumulation of ‘noise’ in the form of junk proteins. Again there is a vicious circle (more irreducible complexity).

Also, even the choice of the letters A, T, G and C now seems to be based on minimizing error. Evolutionists usually suppose that these letters happened to be the ones in the alleged primordial soup, but research shows that C (cytosine) is extremely unlikely to have been present in any such ‘soup.’9 Rather, Dónall Mac Dónaill of Trinity College Dublin suggests that the letter choice is like the advanced error-checking systems that are incorporated into ISBNs on books, credit card numbers, bank accounts and airline tickets. Any alternatives would suffer error catastrophe.10

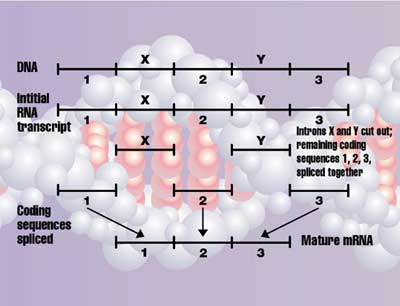

Introns

DNA is not read directly, but first the cell makes a negative copy in a very similar molecule called RNA,11 a process called transcription. But in all organisms other than most bacteria, there is more to transcription. This RNA, reflecting the DNA, contains regions called exons that code for proteins, and non-coding regions called introns. So the introns are removed and the exons are ‘spliced’ together to form the mRNA (messenger RNA) that is finally decoded to form the protein. This also requires elaborate machinery called a spliceosome. This is assembled on the intron, chops it out at the right place and joins the exons together (see also this animation of the spliceosome machinery). This must be in the right direction and place, because, as shown above, it makes a huge difference if the exon is joined even one letter off. Thus, partly formed splicing machinery would be harmful, so natural selection would work against it. Richard Roberts and Phillip Sharp won the 1993 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine for discovering introns in 1977. It turns out that 97–98% of the genome may be introns and other non-coding sequences, but this raises the question of why introns exist at all. [Update, 2011: now we know there is a splicing code; see related articles below.]

Junk DNA?

Dawkins and others have claimed that this non-coding DNA is ‘junk,’ or ‘selfish’ DNA. Supposedly, no intelligent designer would use such an inefficient system, therefore it must have evolved, they argue. This parallels the 19th century claim that about a hundred ‘vestigial organs’ exist in the human body,12 i.e. allegedly useless remnants of our evolutionary history.13 But more enlightened evolutionists such as Scadding pointed out that the argument is logically invalid, because it is impossible in principle to prove that an organ has no function; rather, it could have a function we don’t know about. Scadding also reminds us that ‘as our knowledge has increased the list of vestigial structures has decreased.’14,15,16

While Dawkins has often claimed that belief in a creator is a ‘cop-out,’ it’s claims of vestigial or junk status that are actually ‘cop-outs.’ Such claims hindered research into the vital function of allegedly vestigial organs, and they do the same with non-coding DNA.

Actually, even if evolution were true, the notion that the introns are useless is absurd. Why would more complex organisms evolve such elaborate machinery to splice them? Rather, natural selection would favour organisms that did not have to waste resources processing a genome filled with 98% junk. And there have been many uses discovered for so-called junk DNA, such as the overall genome structure and regulation of genes. Some creationists believe that this DNA has a role in rapid post-Flood diversification of the ‘kinds’ on board the Ark.17

Some non-coding RNAs called microRNAs (miRNAs) seem to regulate the production of proteins coded in other genes, and seem to be almost identical in humans, mice and zebrafish. The recent sequencing of the mouse genome18 surprised researchers and led to headlines such as ‘“Junk DNA” Contains Essential Information.’19 They found that 5% of the genome was basically identical but only 2% of that was actual genes. So they reasoned that the other 3% must also be identical for a reason. The researchers believe the 3% probably has a crucial role in determining the behaviour of the actual genes, e.g. the order in which they are switched on.20

Also, damage to introns can be disastrous—in one example, deleting four ‘letters’ in the centre of an intron prevented the spliceosome from binding to it, resulting in the intron being included.21 Mutations in introns also interfere with imprinting, the process by which only certain genes from the mother or father are expressed, not both. Expression of both genes results in a variety of diseases and cancers.22

Another intriguing discovery is that DNA can conduct electrical signals as far as 60 ‘letters,’ enough to code for 20 amino acids. This is a typical length for molecular switches that turn on adjoining genes. Theoretically, the electrical signals could travel indefinitely. However, single or multiple pairings between A and T stop the signals; that is, they are insulators or ‘electronic hinges in a circuit.’ So, although these particular regions don’t code for proteins, they may protect essential genes from electrical damage from free radicals attacking a distant part of the DNA.23

So times have changed—Alexander Hüttenhofer of the University of Münster, Germany, says:

‘Five or six years ago, people said we were wasting our time. Today, no one regards people studying non-coding RNA as time-wasters.’24

More than just a super hard drive

Actually, DNA is far more complicated than simply coding for proteins, as we are discovering all the time.1 For example, because the DNA letters are read in groups of three, it makes a huge difference which letter we start from. E.g. the sequence GTTCAACGCTGAA … can be read from the first letter, GTT CAA CGC TGA A … but a totally different protein will result from starting from the second letter, TTC AAC GCT GAA …

This means that DNA can be an even more compact information storage system. This partly explains the surprising finding of The Human Genome Project that there are ‘only’ about 35,000 genes, when humans can manufacture over 100,000 proteins.

Reference

- Batten, D., Discoveries that undermine the one gene→one protein idea, Creation 24(4):13, 2002.

Advanced operating system?

Dr John Mattick of the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia, has published a number of papers arguing that the non-coding DNA regions, or rather their non-coding RNA ‘negatives,’ are important components of a complicated genetic network.25,26 These interact with each other, the DNA, mRNA and the proteins. Mattick proposes that the introns function as nodes, linking points in the network. The introns provide many extra connections, enabling what in computer terminology would be called multi-tasking and parallel processing.

In organisms, this network could control the order in which genes are switched on and off. This means that a tremendous variety of multicellular life could be produced by ‘rewiring’ the network. In contrast, ‘early computers were like simple organisms, very cleverly designed [sic], but programmed for one task at a time.’27 The older computers were very inflexible, requiring a complete redesign of the network to change anything. Likewise, single-celled organisms such as bacteria can also afford to be inflexible, because they don’t have to develop as many-celled creatures do.

Evolutionary interpretation

Mattick suggests that this new system somehow evolved (despite the irreducible complexity) and in turn enabled the evolution of many complex living things from simple organisms. However, the same evidence is better interpreted from a Biblical framework. This system can indeed enable multicellular organisms to develop from a ‘simple’ cell—but this is the fertilized egg. This makes more sense; the fertilized egg has all the programming in place for all the information for a complex life-form to develop from an embryo.

It is also an example of good design economy pointing to a single designer as opposed to many. In contrast, the first simple cell to allegedly evolve the complex splicing machinery would have no introns needing splicing.

But Mattick may be partly right about diversification of life. Creationists also believe that life diversified—after the Flood. However, this diversification involved no new information. Some creationists have proposed that certain parts of currently non-coding DNA could have enabled faster diversification,28 and Mattick’s theory could provide still another mechanism.

Hindering science

A severe critic of Mattick’s theory, Jean-Michel Claverie of CNRS, the national research institute in Marseilles, France, said something very revealing:

The circle of life

All living things have encyclopedic information content, a recipe for all their complex machinery and structures.

This is stored and transmitted to the next generation as a message on DNA ‘letters,’ but the message is in the arrangement, not the letters themselves.

The message requires decoding and transmission machinery, which itself is part of the stored ‘message.’

The choices of the code and even the letters are optimal.

Therefore, the genetic coding system is an example of irreducible complexity.

‘I don’t think much of this work. In general, all these global ideas don’t travel very far because they fail to take into account the most basic principle of biology: things arose by the additive addition of evolution of tiny subsystems, not by global design. It is perfectly possible that one intron in one given gene might have evolved—by chance—some regulatory property. It is utterly improbable that all genes might have acquired introns for the future property of regulating expression.’

Two points to note:

This agrees that if the intron system really is an advanced operating system, it really would be irreducibly complex, because evolution could not build it stepwise.

It illustrates the role of materialistic assumptions behind evolution. Usually, atheists such as Dawkins use evolution as ‘proof’ for their faith; in reality, evolution is deduced from their assumption of materialism! E.g. atheist geneticist Richard Lewontin wrote, ‘ … we have a prior commitment, a commitment to materialism. … Moreover, that materialism is absolute, for we cannot allow a Divine Foot in the door.’29 Christian immunologist Scott Todd summarized the evolutionary dogma, ‘Even if all the data point to an intelligent designer, such an hypothesis is excluded from science because it is not naturalistic.’30

Similarly, while many use ‘junk’ DNA as ‘proof’ of evolution, Claverie is using the assumption of evolution as ‘proof’ of its junkiness! This is again a parallel with vestigial organs. In reality, evolution was used as a proof of their vestigiality, and hindered research into their function. Claverie’s attitude could likewise hinder research into the networking capacity of non-coding DNA.

Summary

‘Junk DNA’ (or, rather, DNA that doesn’t directly code for proteins) is not evidence for evolution. Rather, its alleged junkiness is a deduction from the false assumption of evolution.

Just because no function is known, it doesn’t mean there is no function.

Many uses have been found for this non-coding DNA.

There is good evidence that it has an essential role as part of an elaborate genetic network. This could have a crucial role in the development of many-celled creatures from a single fertilized egg, and also in the post-Flood diversification (e.g. a canine kind giving rise to dingoes, wolves, coyotes etc.).

The programs of life

Information is a measure of the complexity of the arrangement of parts of a storage medium, and doesn’t depend on what parts are arranged. For instance, the printed page stores information via the 26 letters of the alphabet, which are arrangements of ink molecules on paper. But the information is not contained in the letters themselves. Even a translation into another language, even those with a different alphabet, need not change the information, but simply the way it is presented. However, a computer hard drive stores information in a totally different way—an array of magnetic ‘on or off’ patterns in a ferrimagnetic disk, and again the information is in the patterns, the arrangement, not the magnetic substance. Totally different media can carry exactly the same information. An example is this article you’re reading—the information is exactly the same as that on my computer’s hard drive, but my hard drive looks vastly different from this page. In DNA, the information is stored as sequences of four types of DNA bases, A,C,G and T. In one sense, these could be called chemical ‘letters’ because they store information an analogous way to printed letters.1 There are huge problems for evolutionists explaining how the ‘letters’ alone could come from a primordial soup.2 But even if this was solved, it would be as meaningless as getting a bowl of alphabet soup.

The ‘letters’ must then link together, in the face of chemistry trying to break them apart.3 Most importantly, the letters must be arranged correctly to have any meaning for life.

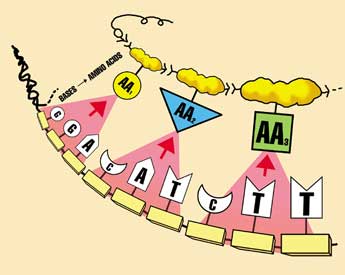

A group (codon) of 3 DNA ‘letters’ codes for one protein ‘letter’ called an amino acid, and the conversion is called translation. Since even one mistake in a protein can be catastrophic, it’s important to decode correctly. Think again about a written language—it is only useful if the reader is familiar with the language. For example, a reader must know that the letter sequence c-a-t codes for a furry pet with retractable claws. But consider the sequence g-i-f-t—in English, it means a present; but in German, it means poison. Understandably, during the post–September-11 anthrax scare, some German postal workers were very reluctant to handle packages marked ‘Gift.’ Return to main text.

References and notes

- Adenine, cytosine, guanine and thymine. They are part of building blocks called nucleotides, which comprise the sugar deoxyribose, a phosphate and a base. In RNA, uracil (U) substitutes for thymine and ribose substitutes for deoxyribose.

- Sarfati, J., Origin of life: instability of building blocks, Journal of Creation 13(2):124–127, 1999.

- Sarfati, J., Origin of life: the polymerization problem, Journal of Creation 12(3):281–284, 1998.

How DNA is transcribed into mRNA with RNA polymerase, then translated into a protein in the ribosome with tRNA ‘adaptor’ molecules. This protein is then escorted by chaperones into a chaperonin so it folds correctly. All this machinery is itself encoded in the DNA, but the DNA can’t be read without this decoding machinery—a vicious circle, or chicken-and-egg problem. Furthermore, most of these processes use energy, supplied by ATP, produced by the motor ATP synthase (right). But the ATP synthase motor can’t be produced without instructions in the DNA, read by decoding machinery using ATP… a three-way circle, or perhaps an egg-nymph-grasshopper problem.

The 20-nanometer motor (height), ATP synthase (one nanometer is one thousand-millionth of a metre). These rotary motors in the membranes of mitochondria (the cell’s power houses) turn in response to proton flow (a positive electric current). Rotation of the motor converts ADP molecules plus phosphate into the cell’s fuel, ATP.

References and notes

- DNA= deoxyribonucleic acid. See Wieland, C., The marvellous ‘message molecule’, Creation 17(4):10–13, 1995. Return to text.

- Dawkins, R., The Blind Watchmaker, W.W. Norton, New York, p. 115, 1986. Return to text.

- Grigg, R., Information: A modern scientific design argument, Creation 22(2):52–53, 2000; creation.com/design-history#aside. Return to text.

- Gitt, W., In the beginning was Information, CLV, Bielenfeld, Germany, 1997. Return to text.

- Popper, K.R., Scientific Reduction and the Essential Incompleteness of All Science; in Ayala, F. and Dobzhansky, T., Eds., Studies in the Philosophy of Biology, University of California Press, Berkeley, p. 270, 1974. Return to text.

- Sarfati, J., Self-replicating enzymes? Journal of Creation 11(1):4–6, 1997; creation.com/replicating. Return to text.

- Fraser, C.M. et al., The minimal gene complement of Mycoplasma genitalium, Science 270(5235):397–403, 1995; perspective by Goffeau, A., Life with 482 Genes, same issue, pp. 445–446. Return to text.

- Gitt, W., Dazzling design in miniature, Creation 20(1):6, 1997; creation.com/dna. Return to text.

- Sarfati, J., Origin of life: instability of building blocks, Journal of Creation 13(2):124–127, 1999; creation.com/blocks. Return to text.

- Bradley, D., The genome chose its alphabet with care, Science 297(5588):1789–91, 13 September 2002. Mac Dónaill’s theory involves parity bits, an extra 1 or 0 added to a binary string to make it add up to an even number (e.g. when transmitting the number 11100110, add an extra 1 onto the end (11100110,1), and the number 11100001 has a zero added (11100001,0). If there is a single error changing a 1 to a 0 or vice versa, the string will add up to an odd number, so the receiver knows that it has not been transmitted accurately. Mac Dónaill found that he could treat certain structural features of the DNA ‘letters’ as a four-digit binary number, with the fourth digit a parity bit. He found that these DNA letters all have even parity, while ‘alphabets composed of nucleotides of mixed parity would have catastrophic error rates.’ Return to text.

- RNA = ribonucleic acid. Return to text.

- Wiedersheim claimed that there were over 180 ‘rudimentary’ structures in the human body, including 86 ‘vestigial’ organs, in The Structure of Man: an Index to his Past History; transl. Bernard, by H. & M., Macmillan, London, 1895. Return to text.

- The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (1993) defines ‘vestigial’ as ‘degenerate or atrophied, having become functionless in the course of evolution.’ Some evolutionists now re-define ‘vestigial’ to mean simply ‘reduced or altered in function.’ Thus, even valuable, functioning organs (consistent with design) might now be called ‘vestigial.’ This seems like changing the rules in the face of a losing argument. Return to text.

- Scadding, S.R., Do ‘vestigial organs’ provide evidence for evolution?, Evolutionary Theory 5(3):173–176, 1981. Return to text.

- See also Bergman, J. and Howe, G., ‘Vestigial organs’ are fully functional, Creation Research Society Books, Kansas City, 1990. Return to text.

- A recent example was certain very short muscles in horse legs that are now known to have a vital role in dampening damaging vibrations. See Sarfati, J., Useless horse body parts? No way! Creation 24(3):24–25, 2002; creation.com/useless based on Nature 414(6866):895–899, 855–857, 20/27 December 2001. Return to text.

- For an overview, see Walkup, L., Junk DNA: evolutionary discards or God’s tools? Journal of Creation 14(2):18–30, 2000; creation.com/junk-dna. Return to text.

- Nature 420(6915):509–590, 5 December 2002. Return to text.

- Gillis, J., ‘Junk DNA’ contains essential information—DNA has instructions needed for growth, survival, Washington Post, 4 December 2002. Return to text.

- Evolutionists call the almost identical sequences ‘highly conserved,’ because they interpret the similarities as arising from a common ancestor, but with natural selection eliminating any deviations in this 5% because precision is essential for it to function properly. Creationists interpret the same evidence as evidence of a designer creating the sequences in a precise way, because that’s necessary for it to function. This is one more example of how allegedly evolution-inspired scientific advances make at least equal sense under a Biblical framework. Return to text.

- Cohen, P., New genetic spanner in the works, New Scientist 173(2334):17, 16 March 2002. Return to text.

- Batten, D., ‘Junk’ DNA (again), Journal of Creation 12(1):5, 1998; creation.com/junkdna. Return to text.

- Coglan, A., Electric DNA: There’s another information superhighway lurking in our genes, New Scientist 161(2173):19, 13 February 1999; citing Jacqueline Barton of the California Institute of Technology, Chemistry & Biology 6(2):85. Return to text.

- Dennis, C., The brave new world of RNA, Nature 418(6894):122–124, 11 July 2002; cited on p. 124. Return to text.

- Mattick, J.S. Non-coding RNAs: The architects of eukaryotic complexity, EMBO Reports 2:986–991, November 2001. Return to text.

- Cooper, M., Life 2.0, New Scientist 174(2346):30–33, 8 June 2002; Dennis, ref. 24. Return to text.

- Ref. 26, p. 32. Return to text.

- E.g. Wood, T.C., Altruistic Genetic Elements (AGEs), cited in Walkup, ref. 17. Return to text.

- Lewontin, R., Billions and billions of demons, The New York Review, 9 January 1997, p. 31; Evolutionist’s blind faith in atheism, regardless of how absurd it seems. Return to text.

- Todd, S.C., correspondence to Nature 401(6752):423, 30 Sept. 1999; A designer is unscientific—even if all the evidence supports one! Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.