‘Parade of mutants’—pedigree dogs and artificial selection

When choosing a pet, many people opt for purebred pedigree dogs. Though they come at a price, it is easier to predict the eventual size, temperament, and needs of a purebred dog breed than for a ‘mutt’. But as a new BBC documentary, “Pedigree Dogs Exposed”,1 shows, the cost of breeding purebred dogs is genetic as well as economic.

All dogs are descendants of a wolf-like ancestor. This ancestor had the genetic diversity that allowed people to breed dogs as different in size as the Chihuahua and the Great Dane. Other traits such as colour, temperament, and exercise needs are just as diverse among the breeds. This great variability is an example of just how much genetic variation is built into the various created animal kinds.2 Other breeds, as will be shown, are the result of downhill mutations.

Genetic specialization

Over many hundreds of years, humans have produced the various breeds by specifically selecting different traits to breed for; there are currently over 200 distinct varieties of dog, but all belong to the same species, and could theoretically breed with each other, though size difference between larger and smaller breeds renders some combinations unlikely.3

Over time, breeding only for certain traits allows great predictability in what a dog’s offspring will look like—a Dalmatian mated with a Dalmatian will produce Dalmatian puppies, and so on. When this occurs regularly, the type of dog becomes an official breed. But this predictability comes at a genetic cost. The breeders have drastically reduced the amount of genetic information in the population of dogs—such as for other coat colours and lengths, or different sizes or temperaments. This sort of selection is done on purpose, but there are other traits that are inadvertently selected for as well.

The bigger dog breeds become susceptible to hip dysplasia, others are plagued by heart problems. The King Charles Spaniel is prone to an extremely nasty condition, syringomyelia (SM), in which the skull is too small to house the brain. In the documentary, veterinary neurologist Clare Rusbridge described the condition: “A burning pain, a piston-type headache, abnormal sensations to even light touch, even items of clothing, a collar, for example, can induce discomfort for these animals.” She believes up to one-third of the breed could be affected by this condition.

Overall, there are 500 genetic diseases which are known to occur in dogs. This is fewer than those documented in humans, but in dogs they occur at a much higher rate. The problem is that when the gene pool has been so depleted, it is not possible to avoid breeding diseased dogs, because that would be impoverishing the gene pool even more, and could lead to new diseases and disorders in a breed. Rusbridge acknowledged this to be true.4

“Mutts”, or even crossbred dogs, have a much lower chance of having these diseases, because many are genetically recessive—a healthy copy of the gene will override a diseased gene. Because the diseases are also often breed-specific, even breeding two purebred dogs of different breeds will normally produce much healthier offspring than a purebred mating. The mutts will have lower instances of disease as well as being slightly longer-lived on average.

A ‘Perfect’ Animal—Dog Shows

Early dog breeding mimicked natural selection, in that dogs were bred to work—the dogs that could herd sheep or cattle, or that could defend against intruders, etc., were the ones that were bred to produce the next generation. This process over time produced the modern breeds. However, with the advent of dog showing in the middle of the nineteenth century, the focus shifted away from function to aesthetics.

Competitive dog-showing, in its pursuit of perfection, has driven the various breeds to ever more drastic extremes in body proportion and shape. The Dachshund’s legs have become much shorter over the last century, but their long back often gives them spinal problems, and they often suffer epilepsy and eye problems as well. The Bull Terrier’s head has been deformed, as has that of the Pit Bull—the documentary’s computer rendering of how breeders have contorted the skull shapes showed how drastically these breeds have changed in less than a century. Bulldogs have slower relative growth of the nasal bones, and this causes breathing difficulties and the need to be born by Caesarian section.

The German Shepherd shows that these changes are carried out for purely cosmetic reasons. There are actually two varieties of German Shepherd: the working variety, which is often used in police forces and as guard dogs, and the show variety. The former looks very much like the original German Shepherd, but the show variety has a very different shape, with their back ends slouching. Orthopedic surgeon Graham Oliver described the gait of the show dogs as ataxic, lacking full coordination and control. This is the case for most of the show German Shepherds in the dog shows that were covered in the documentary.

Extreme artificial selection

In Britain, an already bad situation has been compounded in many ways by the Kennel Club’s breeding and show dog practices. First, the gene pool of the breeds is artificially restricted to the descendants of the originally-registered dogs from the mid-nineteenth century—in some cases, only a handful of dogs. This means that genetic diversity cannot be re-introduced into a breed, even if this means making the population healthier.

Second, there is extreme selection for absolute perfection in appearance—breeders seek to produce dogs which adhere to the breed standard as closely as possible. This causes them to remove dogs that fall short of that standard, such as Dalmatians with non-standard markings, albino dogs, or Rhodesian Ridgebacks with no ridge, from the gene pool of the species, either by simply not mating them, or by culling them as puppies. This renders the overall population even more genetically impoverished.

Third, extreme inbreeding has been the norm—it is common to mate littermates, or to mate a female dog with her “grandfather”, or “mother” to “son”. Evolutionary geneticist Steve Jones criticized the practice: “People are carrying out breeding which would be, first of all, it’s illegal in humans, and second of all, it’s absolutely insane from the point of view of the health of the animals.” Such close interbreeding is done to ‘fix’ certain desirable traits in the line, but it also makes the dogs more disease-prone. The Kennel Club website, www.thekennelclub.org.uk, currently states that “the Kennel Club will not accept an application to register … offspring of any mating between father and daughter, mother and son, and or brother and sister, save in exceptional circumstances, for scientifically-proven welfare reasons.” Even so, the average dog is much more inbred than any human is likely to be.

Because there is no regulation against breeding dogs which are known to carry a genetic disease like syringomyelia, dogs with conditions like this, if they are popular studs, can go on to sire dozens of litters. This spreads the genetic disease throughout the breed.

The Eugenics connection

The Eugenics movement, founded by Darwin’s cousin Francis Galton,5 held that the key to human improvement was in controlling who could reproduce with whom—the idea was to improve the race by eliminating undesirable traits, and in disallowing mixing between ‘races’. While we know today that the eugenicists’ ideas about purity make no scientific sense, the documentary argues that The Kennel Club is one of the few organizations that still operate under the fundamental assumptions of eugenics. Every dog registered with the Kennel Club has an ancestry that goes back to the original registered dogs—no new registrations are allowed, and any litters resulting from breeding with non-registered dogs or breeding between two registered dogs of different breeds cannot be registered.

Because of the eugenicist principles in breeding, puppies that do not conform to the strict requirements of the breed standards are sometimes culled. This is particularly the case with Rhodesian Ridgebacks that lack ridges. While the Kennel Club, both through its spokespeople in the documentary and in the Ethics Code on its site, condemns the practice, the documentary contains statements from breeders saying that they routinely cull puppies without ridges. One even lamented the young veterinarians who refused to cull the healthy puppies! (It should be noted that although the Rhodesian Ridgeback Club code of ethics6 prescribed the culling of ridgeless puppies before the documentary aired, the page has since been modified to prohibit such acts.) The ridge is actually a mild form of spina bifida, so a slightly diseased dog is actually preferred to the healthy animal in this breed.

Genetic impoverishment

All these factors together have made modern breeds very genetically impoverished—in some breeds, only 10% of the genetic variety that was in the breed 40 years ago has been passed down to the current descendants of the breed. For instance, the Pug breed in the UK, although it has 10,000 dogs, has the genetic information equivalent to that of 50 distinct individuals. In 2004, Dr Jeff Sampson wrote:

“Unfortunately, the restrictive breeding patterns that have been developed as part and parcel of the purebred dog scene have not been without collateral damage to all breeds … Increasingly, inherited diseases are imposing a serious disease burden on many, if not all, breeds of dog.”

The Kennel Club, to its credit, has responded to the issues raised by the documentary. It has banned close inbreeding, along with banning the practice of culling healthy puppies for breed points. They have also revised the breed standards to discourage the extreme exaggeration of features to the point that it affects the dog’s health. It also encourages its accredited breeders to make use of any health tests to screen for genetic diseases.

The dangers of inbreeding:

These dogs inherited one stretch of DNA from each parent. We see the good genes and mutations. The dog on the left is the offspring of two distantly related parents, so the mother’s DNA has different defects from the fathers. Every one of her defective genes is masked by the backup copy from the father, and vice versa. But the unfortunate dog on the right is the offspring of close relatives; here, the father and mother have many of the same mutations. So in a number of spots, the dog inherited a pair of mutant genes.

This might explain why God prohibited brother-sister intermarriages from Moses’ day on. But note that mutations are the result of the Fall—God originally created things “very good” (Genesis 1:31), which implies no bad mutations. So humans and animals only a few generations after Creation Week would have had very few mutations, which means that close intermarriage would not have been a problem. Therefore there was no need for God to prohibit close brother-sister intermarriage from the beginning, which solves the old canard, “Who was Mrs Cain?” [See the Creation Answers Book, ch. 8, for more information.)

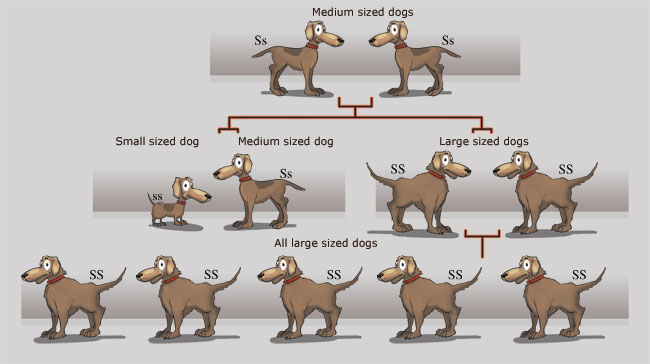

How artificial selection depletes information.

In the example on the right (simplified for illustration), a single gene pair is shown under each dog as coming in two possible forms. One form of the gene (S) carries instructions for large size, the other (s) for small size.

In row 1, we start with medium-sized animals (Ss) interbreeding. Each of the offspring of these dogs can get one of either gene from each parent to make up their two genes.

In row 2, we see that the resultant offspring can have either large (SS), medium (Ss) or small (ss) size. But let’s suppose that breeders want large dogs. They would select the largest dogs in the next generation to breed. Thus only the big dogs pass on genes to the next generation (line 3). So from then on, all the dogs will be a new, large variety. This is artificial selection, but natural selection would work on the same principle, if large dogs would do better in their environment. Note that:

- They are now adapted to their environment, in this case breeders who want big dogs.

- They are now more specialized than their ancestors on row 1.

- This has occurred through artificial selection, and could have occurred through natural selection.

- There have been no new genes added

- In fact, genes have been lost from the population—i.e. there has been a loss of genetic information, the opposite of what microbe-to-man evolution needs in order to be credible.

- Not only genes for smallness were lost, but any other genes these small dogs carried. They may have had genes for endurance, strong sense of smell, and other things, but they are lost from the population. Genes on their own are not selected; it’s the whole creature and all the genes they carried.

- Now the population is less able to adapt to future environmental changes—if small dogs became fashionable, or would perform better in some environment, they could not be bred from this population. They are also genetically impoverished since they lack the good genes that happened to be carried by the small dogs.

Conclusion

The current state of many of the dog breeds shows what happens when selection is taken too far. These dogs, far from being more perfect, ‘evolved’, animals, were described as “a parade of mutants” by one critic in the documentary. Because they are over-specialized, they are more prone to disease and shorter-lived than their ‘mongrel’ relatives. It is clear that both artificial and natural selection work by decreasing the amount of genetic information in a population, which is the exact opposite of what evolution would require.

References

- Unless otherwise noted, all quotes come from the documentary. It was produced and presented by Jemima Harrison, and originally aired 19 August 2008, and is available online at http://vids.myspace.com/. It has had quite an influence on dog-breeding policy in the UK. Return to text.

- See illustration “How information is lost when creatures adapt to their environment”; creation.com/adapt. Return to text.

- Even Great Danes and Chihuahuas can be crossed via artificial insemination. Return to text.

- Rusbridge, C. and Knowler, S., Syringomyelia (SM) Breeding Protocol, www.cavalierhealth.org/smprotocol.htm, 2001–2009. Return to text.

- Grigg, R., Eugenics … death of the defenceless: The legacy of Darwin’s cousin Galton, Creation 28(1):18–22, 2005; creation.com/eugenics. Return to text.

- www.rhodesianridgebacks.org/ethics.html. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.