The Census of Quirinius

Did Luke get it wrong?

Published: 29 December 2011(GMT+10)

(subsequently published in Creation 36(1):42–44, 2014)

During the traditional Christmas season, millions of Christians read the nativity accounts of Matthew and Luke. Luke, great historian as he was, provides information of the timing and circumstances around Jesus’ birth. This connects with the prophecies of the Messiah in the Old Testament, including the timing (Daniel 9) and place (Micah 5:2). Luke 2:1–7 reads:

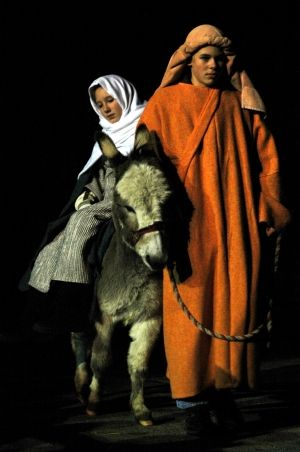

And it came to pass in those days that a decree went out from Caesar Augustus that all the world should be registered. This census first took place while Quirinius was governing Syria. So all went to be registered, everyone to his own city. Joseph also went up from Galilee, out of the city of Nazareth, into Judea, to the city of David, which is called Bethlehem, because he was of the house and lineage of David, to be registered with Mary, his betrothed wife, who was with child. So it was, that while they were there, the days were completed for her to be delivered. And she brought forth her firstborn Son, and wrapped Him in swaddling cloths, and laid Him in a manger, because there was no room for them in the inn. (NKJV)

This passage has been the target for skeptics on several grounds, including the reality and timing of the census, and the need for a journey to Bethlehem. Yet as we have often pointed out, a good rule of thumb is, “the biblioskeptic is always wrong.” So let’s follow the biblical commands of 1 Peter 3:15 and 2 Corinthians 10:5—give reasons for our faith, and demolish opposing arguments.

‘All the world’

Some mock Luke’s phrasing in Luke 2:1: “All the world? Surely Aborigines weren’t included!” This, even in the English translation, is a ridiculously wooden way of reading the text. But the word “world” in this Luke passage is non-universal. As I wrote in Refuting Compromise:

The Greek in this verse is πᾶσαν τὴν οἰκουμένην (pasan tēn oikoumenēn), and it’s the Greek that counts. The basic word translated ‘world’ is οἰκουμένη (oikoumenē), from which we derive the word ‘ecumenical’. Greek scholars recognize that in the New Testament as well as secular Greek literature at the time, oikoumenē was often used to refer to the ‘Roman empire’ only.1 So Caesar Augustus really did initiate a census of all the oikoumenē, i.e., all the Roman Empire (p. 249).

A well regarded commentator on Luke, I. Howard Marshall (1934– ), Professor Emeritus of New Testament Exegesis at the University of Aberdeen, Scotland explains:

ὀικουμένη is ‘the inhabited (world)’, from ὀικέω, ‘to dwell’. It was used of the Roman Empire which was exaggeratedly regarded as equal to the whole world. 2,3

So the NIV is right to render this phrase, “the entire Roman world”.

Census in Quirinius’ time?

Skeptics have argued that Luke got the timing wrong as well. They claim that Quirinius did not become governor until c. 7 AD according to Josephus. Yet according to Matthew’s Gospel, Christ was born before Herod the Great’s death, which occurred in 4 BC. Supposedly, Luke was misled by a great census performed under Quirinius that was very well known.

But this is an absurd charge: even on the face of it, it is not likely that Luke was simply confused, because he showed that he was well aware of this in Acts 5:37: “Judas the Galilean rose up in the days of the census and drew away some of the people after him.” Here, Luke didn’t even need to say which census was being referred to; his original readers would know perfectly well what “the census” referred to. He also used the same word in Greek for census, ἀπογραφή (apographē) as in Luke 2.

There are two main solutions, both recognizing that Luke was aware of the census by Quirinius:

1. This was not the main census of Quirinius, but a first census, which implies at least one more, e.g. great one referred to in Acts. This implies that he twice governed Syria, once around 7 BC and again around AD 7. Sir William Mitchell Ramsay (1851–1939), the archaeologist and professor from Oxford and Cambridge Universities, argued that Quirinius ruled Syria twice.4 This was partly based on the Latin Tiburtine Inscription, discovered in 1746, which referred to someone ruling Syria twice, and Ramsay argued that Quirinius fitted that description.5

Publius Sulpicius Quirinius (51 BC – AD 21) was known to be a most able commander, defeating the Homonadenses tribe in Galatia and Cilicia, in what is now the mountains of Turkey. For this, he was awarded a triumph (a ‘triumph’ was a public procession in honor of a great victory), and after he died, he had a public funeral. This was a contrast to the official governor of Syria, Publius Quinctilius Varus (46 BC – AD 9). Varus was known to be a brutal man, who imposed confiscatory taxes and crucified 2000 Jewish rebels. More importantly, he is now infamous for leading three whole Roman legions to annihilation in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in AD 9—the clades Variana or Varian disaster.

Caesar Augustus (63 BC – AD 14), a good judge of character, may have realized that Varus was not the man to oversee a census. So under this scenario, Augustus appointed Quirinius to perform this duty—Cilicia, the scene of his triumph, was annexed to the province of Syria around this time. The Greek phrase is ἡγεμονεύοντος τῆς Συρίας Κυρηνίου (hēgemoneuontos tēs Syrias Kyrēniou6), which uses a verb participle based on the word hegemon, a lower official title than Governor (“Legate”).

Thus biblical scholar Gleason Archer (1916–2004) suggests:

In order to secure efficiency and dispatch, it may well have been that Augustus put Quirinius in charge of the census-enrollment in Syria between the close of Saturninus’s administration and the beginning of Varus’s term of service in 7 BC. It was doubtless because of his competent handling of the 7 BC census that Augustus later put him in charge of the 7 AD census.7

2. This was not Quirinius’ census at all, but a census before Quirinius’, aka “the census”. The New Testament scholar N.T. Wright argues that πρῶτος (prōtos) not only means ‘first’, but when followed by the genitive can mean ‘before’ (cf. John 1:15, 15:18).8 Wright’s view also has quite a lot of scholarly support, although not universal.9

For example, F.F. Bruce (1910–1990), Ryland professor of Biblical Criticism at the University of Manchester, suggested that the passage should be translated, “This enrollment (census) was before that made when Quirinius was governor of Syria.” Harold Hoehner (1935–2009), Distinguished Professor of New Testament Studies at Dallas Theological Seminary, suggested that the passage should read, “This census was before that [census] when Quirinius was governor of Syria.”10 Therefore the census around the time of Christ’s birth was one which took place before Quirinius was governing Syria, of which Luke was well aware, as shown above.

One or the other of the above possible explanations is far more likely than the skeptics’ claim that Luke mistook the well-known AD census by Quirinius. If that was the problem, there is simply no need to have the word prōtos at all: just say that it happened at the census by Quirinius. The word prōtos must imply that it was the first of more than one census by Quirinius, or it was one before that well-known one. There is perplexity about which of those two meanings is to be preferred, and I am in good company to prefer the meaning ‘before’, but there are others who believe it means the first of two. What is can’t mean is that it was the only census, an event Luke was well aware of.

The journey to Bethlehem

Some have questioned the account because they believe that it’s implausible that a heavily pregnant woman would be forced to travel so far. First of all, distances in Israel are tiny; before 1967, the modern state was only 9 miles wide, or under half the width of the Capital Beltway surrounding Washington DC. It is quite a bit longer, but still, the distance that Jesus’ mother and adoptive father travelled was only about 70 miles. Also, Mary might not have been so heavy; the text just says, “while they were there”, Jesus was born, nothing about being born the night they arrived.

But still, that seems like a lot of trouble to go to. But Luke explained why: the rule was that people had to go to their own place. And as usual, archaeological discoveries have vindicated Luke.

Early in the twentieth century, a papyrus was discovered dating from about AD 104. This contained an edict by Gauis Vibius Maximus, the Roman governor of Egypt, stating:

Since the enrollment by households is approaching, it is necessary to command all who for any reason are out of their own district to return to their own home, in order to perform the usual business of the taxation …

This even used the same word, apographē, translated above as “enrollment”, as Luke used for “census”.

The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia comments:

For example, a British Museum decree of Gaius Vibius Maximus, prefect of Egypt (C.E. 104), ordered all who were out of their districts to return to their homes in view of the approaching census (cf. Lk. 2:1–5).11

This mainly concerned migrant workers, but Raymond E. Brown (1928–1998), no evangelical, suggested that it had a wider context for Jews, who took their genealogies seriously:

One cannot rule out the possibility that, since Romans often adapted their administration to local circumstances, a census conducted in Judea would respect the strong attachment of Jewish tribal and ancestral relationships.12

There are other intriguing papyri that back up Luke’s account. Here is one from a father’s point of view, about his family:

I register Pakebkis, the son born to me and Taasies daughter of … and Taopis in the 10th year of Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus Imperator [Emperor], and request that the name of my aforesaid son Pakebkis be entered on the list … .13

This shows that family registration was a fact of life for Roman subjects.

Conclusion

The evidence backs up what Ramsay wrote after a lifetime of archaeological research on the New Testament:

I take the view that Luke’s history is unsurpassed in regard to his trustworthiness … . You may press the words of Luke in a degree beyond any other historian’s and they stand the keenest scrutiny and the hardest treatment.14

And like a good historian, Luke gives us details that allow us to place the Incarnation at a specific point in history. For him, the theological and the historical were inseparably connected, which is a good reason for us to take both seriously.

Local flood?

Some compromisers use this “all the world” in Luke 2:1 to attack the global Flood taught in Genesis, to teach instead a local flood to fit uniformitarian science. They argue that obviously Augustus never decreed that that literally the whole world would be registered—obviously, his reach never extended to Australia. So, they argue, neither did Noah’s Flood need to cover the whole globe.

In response, first, the word for “world”, οἰκουμένη (oikoumenē), was non-universal, and meant the Roman Empire, as shown in the main article. Second, no one doubts that “all” (Hebrew כּל kol in the Genesis account), may have a non-universal sense in some cases. But in Genesis 7:19, the language is much more emphatic, to remove all possibility of a local flood. “And the waters prevailed so mightily on the earth that all (kol) the high mountains under the whole (kol) heaven were covered.” Leupold points out, “A double ‘all’ (kol) cannot allow for so relative a sense. It almost constitutes a Hebrew superlative. So we believe that the text disposes of the question of the universality of the Flood.”15 Leupold comments on cases like Luke, “However, we still insist that this fact could overthrow a single kol, never a double kol, as our verse has it.”

References

- BDAG, οἰκουμένη, definition 2, listing the examples Acts 17:6 and Acts 24:5. [Bauer, W., Danker, F.W., Arndt, W.F. and Gingrich, F.W., A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature, 3rd ed. Chicago/London: University of Chicago Press, 2000]. Return to text.

- Marshall, I.H., The Gospel of Luke: A Commentary on the Greek Text, p. 98, Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1978. Return to text.

- Marshall cites TDNT V, 157 n. 1. [Kittel, G. and Friedrich, G. (ed.), Theological Dictionary of the New Testament (translated by G.W. Bromiley), Grand Rapids, 1964–76] Return to text.

- Ramsay, W.M., Was Christ born at Bethlehem? 1898. Return to text.

- Marshall, Ref. 2, p. 103. Return to text.

- The KJV uses the Latin transliteration, Cyrenius, of the Greek form, Κυρηνίος, of the Latin name, Quirinius—a real case of loss of information in the translation back and forth. Return to text.

- Archer, Gleason L., Encyclopedia of Bible Difficulties, p. 366, Zondervan, Grand Rapids, MI, 1982. Return to text.

- Wright, Who was Jesus? p. 89, Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK), Great Britain, 1992. Return to text.

- Jared Compton, a Ph.D. student in New Testament at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, summarized the pros and cons in Once More: Quirinius’s Census, Detroit Baptist Theological Journal, Fall 2009, pp. 45–54; biblearchaeology.org/post/2009/11/01/once-more-quiriniuss-census.aspx. Return to text.

- Hoenher, H., Chronological Aspects of the Life of Christ, p. 21, Zondervan, 1978. Return to text.

- Bromiley, Geoffrey W, ed., The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, p. 655, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1995. Return to text.

- Brown, R.E., The Birth of the Messiah: A Commentary on the Infancy Narratives in Matthew and Luke, p. 549, Doubleday, NY, p. 549, 1993. Return to text.

- Grenfell B.P. and Hunt, A.S., eds., The Tebtunis papyri: Part II, Egypt Exploration Society, Greco-Roman branch, p. 84, Oxford Iniversity Press, 1907. Return to text.

- William M. Ramsay, Luke, The Physician, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1908, pp. 177–179. Return to text.

- Leupold, H.C., Exposition of Genesis 1:301–302, Baker Book House, Grand Rapids, MI, USA, 1942; ccel.org/ccel/leupold/genesis.ix.html. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.