Agnosticism

Religious ‘nones’,1 such as agnostics and atheists, are on the rise in many Western countries.2 The ‘New atheists’ such as Richard Dawkins have likely contributed to this trend—using so-called ‘science’ (especially evolution and deep time) to create uncertainty about God in a lot of people. Many people are aware of the rise in atheism, but less talked about is the rise of agnosticism. In fact, more people self-identify as agnostics than atheists. So what is agnosticism? And how can Christians respond to it?

What is agnosticism?

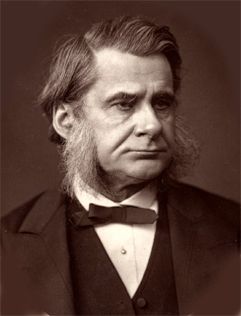

The term ‘agnostic’ was first coined by ‘Darwin’s Bulldog’ Thomas Henry Huxley in the 19th century. Fundamentally, agnostics are unsure about God’s existence. However, this comes in a few different forms.

The first is a personal stance: “I don’t know if God exists or not.” This is often called weak agnosticism. It doesn’t make any claims beyond what the agnostics themselves are uncertain of. They may think we can know in principle whether God exists or not, it’s just that they don’t know.

The second is a universal claim: “We cannot know if God exists or not.” This is often called strong agnosticism. It’s actually a claim to knowledge. It makes the claim that there isn’t enough evidence for anyone to know whether God exists or not.3

Agnosticism and atheism

Agnosticism is often closely linked with atheism. Many atheists and agnostics share a common ‘lack of belief in God’. But all sorts of things ‘lack belief in God’—agnostics and atheists, as well as cats, spiders, roses, bacteria, rocks, etc.

To clarify, Richard Dawkins uses a scale of certainty from 1 to 7; 1 representing someone certain that God exists, and 7 representing someone certain that God doesn’t exist. Where does Dawkins stand?

“6. Very low probability, but short of zero. De facto atheist: ‘I cannot know for certain but I think God is very improbable, and I live my life on the assumption that he is not there.’ …

“I count myself in category 6, but leaning towards 7—I am agnostic only to the extent that I am agnostic about fairies at the bottom of the garden.”4

Dawkins doesn’t just ‘lack a belief in God’ as rocks do. Rather, he is almost certain that God doesn’t exist, and he says he is convinced enough to live as if God doesn’t exist. But, he still thinks he can’t be absolutely certain about whether God exists or not.

There are all sorts of reasons why self-styled ‘agnostics’ and ‘atheists’ don’t like one or the other label. However, there is rarely any difference in what each actually stands for. Most ‘agnostics’ think the probability of God’s existence is very low, and live as if God doesn’t exist.

Strong agnostics are an exception. Those we might label ‘atheist agnostics’, like Dawkins, disavow absolute certainty regarding their atheistic conclusions, but they think it’s possible to come to a best explanation of the evidence. Strong agnostics reject this claim. They think the question of God’s existence is unanswerable.

Agnosticism: the proper starting point?

Agnostic Robin Le Poidevin proposes that weak agnosticism should be the starting point for everyone: “There should be no presumption of atheism, and indeed no presumption of theism either. The initial position should be an agnostic one, which means that theists and atheists share the burden of proof.”5

But note the ethical force in his statement; “The initial position should be an agnostic one [emphasis added]”. Why should I presume ignorance about God’s existence? Is that the only way to give all the claims a fair hearing? First, that’s simply not true; agnosticism is a bias, so it’s no less free from the dangers of confirmation bias than theism or atheism. If we presume not to know whether God exists, we may treat the truth superficially and improperly preserve a pretended neutrality between the options. Second, from within agnosticism this only amounts to a recommendation, not an obligation. Agnosticism cannot ground objective morals.

Theism, on the other hand, is the only option that can ground moral obligation. As such, if we have an objective moral duty to presume anything about God’s existence, such a duty itself constitutes evidence for God. And since God is the ultimate good, if He were to command us to presume anything, He would command us to presume the truth, i.e. that God exists.

Agnosticism, knowledge, and certainty

Agnosticism of all varieties strongly rejects the statements “I know God exists” and “I know God doesn’t exist”. Dawkins’ affirmation of agnosticism shows why:

“I am agnostic only to the extent that I am agnostic about fairies at the bottom of the garden.”6

Few people in ordinary parlance would have any hesitation about saying “I know fairies don’t exist”. But Dawkins confesses himself agnostic about the existence of fairies. Why? It’s theoretically possible that fairies could exist somewhere we haven’t looked.

This is a strange use of language. Dawkins knows this, which is presumably why he prefers to call himself an atheist. For instance, I know I have a left hand. I can see it, feel it, and use it. But I can’t rule out the theoretical possibility that I don’t have a left hand, and that I’m plugged into the Matrix, which stimulates my brain to make me believe I have a left hand. And yet practically nobody will say that I’m wrong for saying “I know I have a left hand”.7 In the same way, if an atheist says “I know there’s no God”, they’re not saying that their atheism is beyond all possible doubt. Likewise for the theist who says ‘I know God exists’. We don’t need absolute certainty to say we know something.

Agnosticism: beyond all reasonable doubt?

But might the agnostic just demand a high level of certainty to justify claiming to know whether God exists or not? For the strong agnostic, this would mean that nobody can know beyond all reasonable doubt if God exists or not. But to know this, the strong agnostic would need practically exhaustive knowledge of what everyone can know about God! And since theism (and atheism) can be doubted, some people may be in a better position to know if God exists than others. Some people might have a better grasp of the evidence than others, or (if God exists) God may have revealed himself clearly to some people. Strong agnostics are just ordinary people; they cannot know what everyone else can know about God.

However, may not weak agnostics still demand extremely high levels of certainty to justify knowing if God exists or not? After all, they may just happen to be in a poor place to know if God exists or not.

This also has a number of problems. First, either God exists, or He doesn’t. And, theism and atheism imply starkly different worlds. Atheism is a world of no objective purpose, meaning, beauty, or value. Theism expects science to work; it’s a massive accident if God doesn’t exist. But this contradicts strong agnosticism, which entails that theistic and atheistic worlds must be indiscernible. It also means weak agnosticism is flawed. The wildly different implications of theism and atheism make it unreasonable to remain agnostic forever.

Second, the weak agnostic might be unreasonably incredulous regarding the evidence for God. For instance, most Muslims reject the historicity of Jesus’ death by crucifixion based on the Koran (e.g. Surah 4:157), despite the fact there is overwhelming evidence that Jesus died by crucifixion. Muslims refuse to accept an obvious truth due to a deeply held prior commitment. If so many people can be blinded to well-evidenced truths due to a faulty bias, it’s not hard to see that the same is possible for the agnostic.8

Third, it assumes that their allegedly poor position to know about God is permanent. Rather, a person’s ability to know truths fluctuates with changing circumstances. It may be that they were once in a better position to know, or that they will come into a better position to know. The weak agnostic’s ability to know about God is in principle provisional.

Finally, a dogged stance of doubt in the face of uncertainty is not very reasonable. For instance, Jesus said: “Ask, and it will be given to you; seek, and you will find; knock, and it will be opened to you” (Matthew 7:7). The psalmist said: “Oh, taste and see that the Lord is good!” (Psalm 34:8). God’s goodness is worth grasping, and He is willing to answer those who seek after Him. As such, even if there is such a thing as reasonable uncertainty, that need not translate (and if God exists, certainly should not translate) into reasonable doubt.

Agnosticism and God’s ‘hiddenness’

Does the nature of God prevent us from knowing if He exists or not? After all, we can’t see or touch God. Still, the answer is no. We can’t see or touch electrons, but that doesn’t stop us from knowing that they exist. Nor does it matter that we can’t know God exhaustively. We don’t need to know everything about cars or quarks to know if they exist.

But doesn’t God have to make himself known to everyone sufficiently to make them culpable for not believing in Him? He does, and the Bible says He does (Romans 1:18–20, see also Is God obscure and arbitrary in what He wants from us?). However, the Bible doesn’t say that God is always obvious to everybody. Nor would God have to be to make people morally culpable for rejecting Him. God is not duty bound to make himself constantly obvious to sinners who consistently reject Him.

Conclusions

Agnosticism entails uncertainty about God. It is often closely linked with atheism. However, by tying knowledge too closely to certainty, it ends up as a prejudice against God. The opposite of faith is doubt, not just outright denial. The correct response to doubting God is not to withhold belief, but this: “I believe; help my unbelief!” (Mark 9:24). If agnostics are truly unsure about God, then they can already see that faith in God is not unreasonable. Rather than a dogged stance of doubt, it is better to ‘run’ with the reasonableness of belief in God with an open mind. “For everyone who asks receives, and the one who seeks finds, and to the one who knocks it will be opened” (Matthew 7:8).

References and notes

- That is, those who identify their religious affiliation on surveys as ‘none’ or ‘no religion’. Return to text.

- America’s Changing Religious Landscape, Pew Research Center, www.pewforum.org, accessed 28 July 2015. Return to text.

- We can perhaps further divide strong agnosticism into provisional and principled versions; i.e. the evidential situation may be provisionally insufficient to justify knowledge of whether God exists or not, though it may be sufficient at a future date; or it may be in principle impossible to know if God exists or not. Return to text.

- Dawkins, R., The God Delusion, Mariner Books, New York, pp. 73–74, 2008. Return to text.

- Le Poidevin, R. Agnosticism: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press (Kindle Edition), Kindle Locations 1010–1011, 2010. Return to text.

- Dawkins, ref. 4, p. 74. Return to text.

- Some philosophical skeptics might press the point by saying ‘we can’t know anything’ or ‘we can’t know anything for certain’. However, both statements are self-refuting. If we can’t know anything (for certain), then we can’t know that statement is correct (for certain). And there’s no reason to think those statements are sole exceptions to the rule (i.e. ‘we can’t know anything (for certain) except this proposition’); there’s nothing about that statement that endears itself to us as uniquely true. We seem to know many things, and we cannot live as if we know nothing. There may even be some things we might know for certain (such as e.g. our own awareness of being in pain at a point in time). Philosophical skepticism is implausible and unliveable. Return to text.

- The agnostic may of course retort that this could be true of any view, and he would be right. But that only proves that we need to be careful about how we assess the evidence if we want to know the truth, not that the agnostic is justified in his ignorance. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.