The hyena—a creature we love to hate

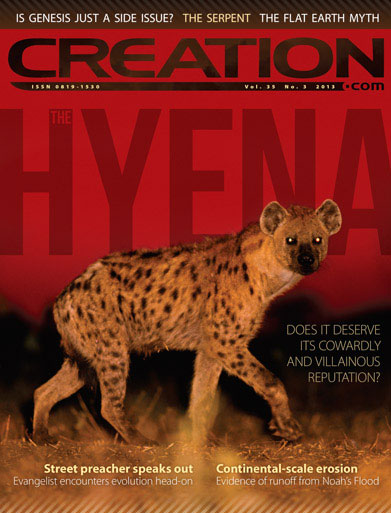

Spotted hyena

Crocuta crocuta

Adult body size:

55–80 kg (120–180 lb)

Habitat range:

Throughout sub-Saharan Africa, in savannah, arid semi-desert, dry woodlands, and rocky mountainous forests

Mainly eats:

Zebra, wildebeest, buffalo

Also eats:

Scavenged carrion—but this is usually no more than 5% of the diet

Hyenas, widely feared and despised, hardly ever feature in wildlife documentaries and magazines. In popular media, hyenas are stereotypically portrayed as being cowardly and villainous—witness Disney’s three spotted hyenas1 in the children’s animated movie The Lion King.2

African proverbs refer to the hyena in less-than-complimentary terms, e.g.:3

- The cry of the hyena and the loss of the goat are one.

- Nothing that enters the mouth of a hyena comes out again.

- The dog and his collar are both booty of the hyena.

- If the hyena eats the sick man he will eat the whole one.

- It is the stinking bit of meat that catches the hyena.

- A cowardly hyena lives for many years.

And there’s even a proverb that recognizes that people’s revulsion for the hyena might go too far:4

- Every fault is laid at the door of the hyena, but it does not steal a bale of cloth.

Scavenger or hunter?

Many people in the west are accustomed to thinking of the hyena only as a scavenger, as in The Lion King. Actually, three hyena species (the spotted, brown and striped hyenas) are both hunters and scavengers. The fourth species of hyena, the diminutive aardwolf, is insectivorous (see Aardwolf).5 As hyenas are primarily nocturnal animals (but may remain outside their lairs for a few hours after sunrise), most hunting or foraging for food occurs at night.

Aardwolf

Proteles cristata

Adult body size: 10 kg (22 lb)

Habitat range: The savannahs of central and south-eastern Africa

Mainly eats: Termites

Also eats: Other insects, especially beetle larvae and maggots (which is why aardwolves are often found near animal carcasses, though they do not eat the carrion itself)

A spotted hyena gets most of its food by hunting, usually alone, and can bring down an adult wildebeest up to three times its bodyweight.6,7 But when hunting in packs of typically 10 to 25, they can kill prey as large as the giraffe and the African Cape buffalo! They do not use stealth. Hyenas are endurance hunters who doggedly chase the selected prey until a weaker member of the herd becomes winded and lags behind—then they close in for the kill. Their large hearts (1% of their bodyweight) provide them with the stamina to maintain a speed of 40–50 km/hr (25–30 mph) for over five kilometres (3 miles), and 60 km/hr (35 mph) for short distances.8,9 An adult hyena can eat 14 kg (30 lb) of meat in 10 minutes. A group of 23 hyenas has been observed to completely consume a full-grown wildebeest in just 13 minutes.10

Man-killers

Spotted and striped hyenas are renowned for killing people, especially women and young children, or sick or infirm men. Hundreds of cases have been documented, right up to the present.11,12,13 On occasion, hyenas have waited at dawn outside people’s huts and attacked them when they opened their doors, or opportunistically ambushed people walking on isolated roads at night.

Human hair has been found in fossilized hyena dung.14 Striped hyenas are said to scavenge on human corpses—in Turkey, stones are placed on graves to stop striped hyenas digging the bodies out.

Bone-crushing jaws

Spotted, striped and brown hyenas are renowned for the bone-crushing strength of their jaws. Massive jaw muscles and a special vaulting to protect the skull against large forces enable spotted hyenas to generate roughly nine thousand newtons of bite force at their primary bone-cracking teeth—several times that of human jaws. They can crack open giraffe leg bones up to 7 cm (3 in) across.10 Spotted hyenas can digest all organic components in bones, not just the marrow. The calcium from the bones readily whitens their excrement.

The aardwolf’s jaws are weaker than in other hyenas, and it has greatly reduced cheek teeth, sometimes even absent in the adult, but otherwise has the same dentition as the other three hyena species.

The hunter, hunted

While popular belief has hyenas stealing kills from lions, the opposite is actually true—more lions steal kills from hyenas.15 The aggression shown by hyenas to lions, and vice versa, is intense. Hyenas are major predators of lion cubs, and have been known to even successfully attack and kill an isolated adult lioness. But they are careful to avoid adult lion males, which are extremely aggressive toward hyenas, killing them at every opportunity, without eating them.15

Hyenas are also deliberately hunted by man. Following attacks on children in Mozambique, for example, local authorities completely eradicated hyenas in that area.13

Brown hyena

Parahyaena brunnea

Adult body size: 45 kg (100 lb)

Habitat range: The arid southwest of Africa, particularly the Kalahari and Namib deserts, but also in scrublands, woodland savannah, and grassland

Mainly eats: Scavenged carrion (including dead marine creatures stranded by the tide, e.g. crabs and whales—thus it is also known as the ‘strandwolf’)

Also eats: Fruits, vegetables, mushrooms, eggs and also fish, insects, birds and small mammals that it hunts itself

Brown hyenas and striped hyenas have longer hair than the spotted hyena. Like the aardwolf, their mane becomes erect when they are frightened or aggressive. All hyenas are strongly territorial, using the paste of an anal pouch gland to scent mark grass, tree trunks, and rocks.

Striped hyena

Hyaena hyaena

Adult body size: 35 kg (75 lb)

Habitat range: Throughout northern Africa to Arabia, Turkey, the Middle East (it is Lebanon’s unofficial national animal), and western India, across incredibly diverse habitats/terrain

Mainly eats: Scavenged carrion

Also eats: Small mammals that it hunts itself (e.g. wild boar, porcupines), fruit, grasshoppers, village garbage

Laughing like a hyena?

The spotted hyena is very vocal, making grunts, whines, lows as well as the ‘laugh’-like sound for which it is famous, which can be heard up to 4.5 km (2.8 miles) away.16 Researchers say that a hyena’s ‘giggle’ is not actually laughter, but a sound made in various kinds of ‘social conflict’, e.g. when fighting over food.17

‘Evolutionary tree’ problems

Evolutionists have puzzled over where to put hyenas on the supposed evolutionary ‘tree’, at various times linking them to the cats (Felidae), dogs (Canidae), or civets (Viverridae).

Hyenas are similar to the felines and viverrids in their grooming, scent marking, and other behavioural aspects. However, like canines, hyenas are non-arboreal, cursorial (endurance-running) hunters with non-retractable nails (ideal for making sharp turns) and they catch prey with their teeth rather than their claws.

The four hyena species are therefore grouped in their own family, the Hyaenidae—the smallest family in the order Carnivora, and one of the smallest in the class Mammalia.

The hyena’s similarities with cats, dogs and civets reflect not common ancestry but instead a common designer—One who might be said to have specifically designed the stark differences between non-related creatures in order to deliberately thwart attempts at naturalistic explanation (Romans 1:20).18

Figure 1: Hyena skulls have been found in caves in the UK and Europe, indicating they once lived there. The above painting is on the wall of the famous Chauvet cave, France. Evolutionists cannot agree on their ‘dating’ of the “exquisitely rendered” paintings, said to be “too magnificent for their time”—see creation.com/chauvet-cave. From the Bible’s timeline we can see the caves were formed during the Genesis Flood about 4,500 years ago, with the paintings being drawn since then. Man has been intelligent, and artistic, from the beginning.

Credit: CC-BY-SA Carla Hufstedler via Wikipedia

The Hyaenidae ‘family’ probably equates to the biblical ‘kind’ referred to in Creation Week and again at the Genesis Flood. Noah didn’t need to take pairs of the four hyena species—he only needed two hyenas; from which all hyenas are descended today (and probably the much larger extinct cave hyena). And just as the horse pair on the Ark probably were striped (a characteristic which all horse varieties except the zebra and quagga have subsequently lost), it’s likely that the hyena pair had stripes too—which have been lost from spotted (and diminished in brown) hyena populations today.19

Incredibly, evolutionists have proposed that a hyena-like animal could have been the ancestral land mammal from which whales evolved. See From hyena to whale?

Clever hyenas leave chimps for chumps

Much to the astonishment of researchers, hyenas outperformed chimpanzees when it came to solving a complex problem that required teamwork.

“The first pair walked in to the pen and figured it out in less than two minutes,” said Christine Drea, an evolutionary anthropologist at Duke University, who led the study. “My jaw literally dropped.”20

Researchers frequently encounter evidence that does not fit the evolutionists’ expectation that apes, as ‘our closest evolutionary relatives’, would be the animals to most closely match the intelligence of humans.21 It was reported in New Scientist: “When the researchers have tried to publish their work on cooperative hyenas, they’ve run into trouble, because their peers ‘were convinced that hyenas simply couldn’t behave in such ways’.”22

Echoes of a pre-Fall diet

According to Genesis 1:30, hyenas were originally vegetarian. Even in today’s post-Fall world, in some areas hyenas are known to eat large quantities of fruit. In its desert habitats, the tsama melon and the gemsbok cucumber provide the brown hyena not just food, but also water—the tsama melon has a water content of more than 90 per cent. On one night a single brown hyena was observed to eat 18 tsama melons—providing it with about 11 litres of water, and the equivalent energy of nearly one kilogram of fresh meat.23 Elsewhere, a major reported threat to the striped hyena’s continued existence is from humans who kill them for eating fruit crops.24

The Bible is the key to making sense of today’s world

As already mentioned, the savagery of man-eating hyenas leads to them soon being eliminated from that area. Coupled with what the Bible says (Genesis 9:5), it provides an insight into why the hyena has disappeared from Europe (see Figure 1) and America (see Do American pronghorn run faster because of hyenas?). Perhaps this is a parallel to the disappearance of dinosaurs, too?25

It’s the biblical account of history, not man’s attempts at godless explanations, that provides us with the proper basis to understand the various creatures in the world today—distinct ‘kinds’ of animals such as the hyena, with a geographical distribution reflecting post-Flood dispersal from the Ark. And the brown and spotted hyena’s loss of stripes, and the aardwolf’s mutational deterioration of its molars to mere ‘pegs’ (now largely limiting it to licking up termites for sustenance), are right in line with Romans 8:20–22’s world “in bondage to decay”. A world going downhill, where useful design features are being lost, not ‘created by evolution’.

As the hyena might say if it could talk, this is no laughing matter. No wonder the whole creation groans as it “waits with eager longing for the revealing of the sons of God.” (Romans 8:19)

Do American pronghorn run faster because of hyenas?

The brazenly evolution-indoctrinating book Billions of years, amazing changes: The story of evolution, quotes poet Robinson Jeffers:

“What but the wolf’s tooth whittled so fine the fleet limbs of the antelope?”

The book then claims that American pronghorn antelope ‘evolved’ their capacity for amazing speed (45 mph (with bursts of near 60) for several miles) thanks in part to the hyena:

“More than ten thousand years ago, pronghorns were chased by much speedier predators: the North American cheetah and a species of long-legged hyena. Today the pronghorn is probably amazingly fast because it evolved with swift predators that are now extinct.”26

But the ‘evolutionary’ processes that evolutionists point to as happening today, viz. natural selection and mutations, aren’t really ‘evolutionary’ at all, in the sense of turning slow antelope into swift ones. Natural selection can only favour the fastest existing antelopes. And observational reality shows mutations cannot generate the creative increase in genetic information that the evolutionary process demands—just the opposite, in fact.27

So the question is not what, but who ‘whittled so fine the fleet limbs of the antelope’? He is the Lord, the Creator God of the Bible.28 And He did this during Creation Week, about 6,000 years ago. Any interaction between hyenas and pronghorn antelopes in North America was not the fictional evolutionary “ten thousand years ago” but rather post-Flood, i.e. after their ancestors had come off Noah’s Ark, sometime during the past 4,500 years.

From hyena to whale?

Evolutionists have hypothesized that whales evolved from a land animal similar to a hyena (see ‘Pachyaena’ photo above left), although they currently propose a wolf-like creature called ‘Pakicetus’ (which they once pictured as a seal-like creature29—see photo above right).

However, how many parts of a land animal would have to change by chance mutations to become a whale? In his book Evolution: The Grand Experiment—Vol. 1,30 Dr Carl Werner explains that, at the very least:

References and notes

- Named: Shenzi, Banzai and Ed. Return to text.

- Glickman, S., The spotted hyena from Aristotle to the Lion King: Reputation is everything, Social Research 62:501–537, 1995. Return to text.

- Laughing at life—a hyena fanlisting, www.heartofsnow.net, acc. 3 April 2013. Return to text.

- Another example would be the erroneous perceptions of hyenas being hermaphrodite or of exhibiting homosexual behaviour—views that likely arose because the genitalia of spotted hyenas superficially appear similar externally in both sexes. The Marshall Cavendish International Wildlife Encyclopedia 11:1280–1282, 1991. Return to text.

- Species information presented in this article is drawn from various of the source references listed here, including The IUCN Hyaena Specialist Group, www.hyaenidae.org, acc. 3 April 2013. Return to text.

- Watts, H. and Holekamp, K., Hyena societies, Current Biology 17(16):R657–R660, 2007. Return to text.

- Holekamp, K., Spotted hyenas, Current Biology 16(22):R944–R945, 2006. Return to text.

- Hyena facts, www.bbc.co.uk/bigcat/animals/hyenas/hyenas.shtml, acc. 4 April 2013. Return to text.

- Is the hyena a cowardly scavenger or do they hunt for their own food?, www.africa-wildlife-detective.com/hyena.html, acc. 4 April 2013. Return to text.

- Michigan State University special report: About spotted hyenas, 2008, special.news.msu.edu, acc. 4 April 2013. Return to text.

- Man-eating hyenas spread fear in Malawi, news.bbc.co.uk, 9 January 2002, acc. 4 April 2013. Return to text.

- Mozambique: Hyenas kill seven children in Niassa, at allafrica.com, 28 April 2011, acc. 4 April 2013. Return to text.

- Kanani, B., Hyena pack attacks sleeping family, kills 2 kids, abcnews.go.com, 19 July 2012, acc. 4 April 2013. Return to text.

- Hoffman, S., Oldest human hairs found in hyena dung fossil, www.livescience.com, 10 May 2009, acc. 4 April 2013. Return to text.

- Lions killing hyenas, at www.kalahari-trophy-hunting.com, acc. 7 April 2013. Return to text.

- Spotted Hyena—Crocuta crocuta, animals.nationalgeographic.com.au/animals/mammals/hyena/, acc. 4 April 2013. Return to text.

- Moskowitz, C., Hyena’s laugh actually fighting words, 5 May 2009, www.livescience.com, acc. 4 April 2013. Return to text.

- For more see Chap. 6, “Argument: Common design points to common ancestry”, in: Sarfati, J., Refuting Evolution 2, Creation Book Publishers, updated edn 2011, available creation.com/store. Return to text.

- See Catchpoole, D., Zebra or horse? A zorse , of course!, Creation 30(1):56, 2007; creation.com/zorse. Return to text.

- Hyenas outperform chimps in solving problems requiring teamwork, tests prove, newswatch.nationalgeographic.com,5 October 2009. Return to text.

- E.g. see: Bird brain matches chimps (and neither makes it to grade school), Creation 19(1):47, 1996; creation.com/bird-brain-matches-chimps. Return to text.

- Blum, D., Justice for all, New Scientist 202(2707):44, 2009. Return to text.

- Fruit-eating hyenas, p. 60 in: Lovegrove, B., The living deserts of southern Africa, Return to text.

- Laughing at life—a hyena fanlisting: Striped hyena, www.heartofsnow.net/hyena/striped-hyena.php, acc. 5 April 2013. Return to text.

- As per this extract from chapter 19, “What about dinosaurs?”, in The Creation Answers Book: “All the kinds of land animals (including dinosaurs) and birds survived aboard the Ark, repopulating the Earth afterwards. Since then, many creatures have gone extinct, not just dinosaurs, in an ongoing display of the Curse on Creation. Just as with the dodo, it’s likely that some dinosaurs perished through human influence, e.g. because of being a direct threat to man’s safety or because of loss of habitat (to agriculture or urban encroachment). A modern parallel can be seen in that the tiger, the rhino and the elephant have either died out or are on the ‘endangered species’ list in many parts of South-East Asia through the ongoing post-Babel dispersion of man. Heroic accounts of brave young men in Indonesia slaying ‘rogue’ tigers and elephants bear a striking parallel with centuries-old stories of ‘St George and the Dragon’, Beowulf, etc, where the dragonslayers were also protecting others.” Return to text.

- Extract from p. 78 of: Pringle, L., Billions of years, amazing changes: The story of evolution, Boyds Mills Press, Inc., Pennsylvania, USA, 2011. For a comprehensive paragraph-by-paragraph rebuttal of the contents of that book see creation.com/pringle-review. Return to text.

- For more on this, see: Catchpoole, D., The 3 Rs of Evolution: Rearrange, Remove, Ruin—in other words, no evolution!, Creation 35(2):47–49, 2013. Return to text.

- For an example of His handiwork in this area see creation.com/elastic-tendons. Return to text.

- Williams, A. and Sarfati, J., Not at all like a whale, Creation 27(2):20–22, 2005; creation.com/pakicetus. Return to text.

- Based on pp. 42–54 in: Werner, C., Evolution: The Grand Experiment Vol. 1, New Leaf Press, Green Forest, AR, USA, 2007. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.