Heard of elephants?

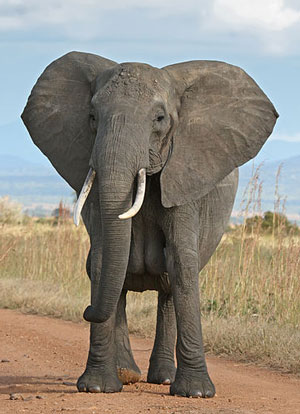

The majestic elephant is perhaps the best known, and most admired, of the world’s wild animals.

There are two main kinds of elephants: the African elephant (Loxodonta africana) and the Asian (Indian) elephant (Elephas maximus).1 The African elephant is the heaviest living land animal, weighing up to 7,500 kg (seven tons) and standing three to four metres (10 to 13 feet) high at the shoulder (the only taller living animal is the giraffe). No other land animal known to be alive today weighs even half as much as an African elephant.2 The Asian elephant is not as large as its African cousin, having a maximum weight of 5,500 kg (five tons) and a shoulder height of three metres (10 feet). It also has much smaller ears and a more domed head, and while both male and female African elephants have tusks, most female Asian elephants do not.3,4

Both belong to the order Proboscidea, a name derived from their most easily recognisable feature, the trunk (or proboscis). This trunk is used in a remarkably wide range of activities: it is powerful enough to be used as an extra limb, to uproot bushes and trees and deliver a crippling blow, yet it can also perform actions demanding great skill and concentration. The tip is especially sensitive, comprising a finger-like ‘lip’ able to pick up small leaves and berries.

The trunk also plays an important role in respiration and the elephant’s sense of smell. It can also suck up as much as four litres (about one gallon) of water at a time, expelling the contents into the mouth for drinking or spraying it over the body to clean itself. Alternatively, it can be filled with dust, which is then blown over the back and flanks as protection against the heat of the sun and the bite of insects. When riverbeds are dry, the elephant is known to use its trunk to locate water, digging pits up to three metres (ten feet) deep with the appendage, and sucking up the moisture that oozes into the pit.5

The other most characteristic feature of the elephant is its curved tusks, which are actually incisor teeth growing from the upper jaw. The first set is temporary, growing to a length of about five centimetres and remaining in place for about a year, after which time they are replaced by the permanent tusks growing behind them.6 In the African male, they average 1.8 m (6 feet) long, but have been reported up to 3.5 m (about 12 feet) long (measured along the curve), with the heaviest single tusk ever recorded weighing 107 kg (235 pounds).7

Colossal cavalry

It’s hard to imagine what it must have been like for ancient civilizations catching sight of these imposing creatures for the first time in war.

Hannibal, the great Carthaginian general of the third century BC, gave the Romans their first look at the elephant in 255 BC when he defeated the Roman army in the battle of Tunis. He then took the animals onto European soil in 218 BC, including them in the legendary army he marched across the Alps into Italy during the Second Punic War (between Rome and Carthage).

How terrifying it must have been for the Romans to see their enemy’s cavalry ranks bolstered by incredibly tall, strong creatures armed with dangerous-looking tusks and unusually long snouts! As sturdy pack animals, the elephants quickly proved their tactical importance in their willingness to charge both men and horses — not to mention the panic such action created among the Romans and their steeds.8

The Carthaginians, however, were not the first to use war elephants; they were first used in India, and this use was known to the Persians in the fourth century BC. However, as many of the 38 elephants Hannibal took across the Alps died during the journey, they were soon abandoned as war animals.

Divinely designed

Elephants live in a wide variety of habitats, from desert margins to savannahs to woodlands and tropical forests to mountainous country such as the slopes of Mt Kilimanjaro.9,10 This ability of the elephant to occupy a broad range of habitat types is largely due to its remarkable design features; notably its trunk.

Being able to pluck its food from low ground cover, medium sized shrubs, and trees up to five metres high means that the elephant is not limited to particular habitat types by the height of vegetation. Tusks, trunk and great weight working in tandem enable elephants to break or push over trees in order to feed on otherwise inaccessible vegetation at the top, and they also can shake loose seedpods or fruits that are out of reach. Also, bark can be stripped and roots dug up for eating.11

Elephants are sometimes called pachyderms (from Greek for ‘thick skin’), because their skin is almost an inch (2.5 cm) thick. Its characteristically wrinkled appearance is caused by soft pimples or papillae. These help temperature regulation by increasing the area of the skin surface. The African elephant’s enormous ears also help in the cooling process, providing both an extended skin area for heat loss, and a handy set of giant ‘fans’.12

Although the elephant appears heavy and ungainly, its comparatively inflexible skeleton with vertical column-like legs and nearly horizontal spine is well designed to support its enormous weight.13 Its large feet provide a broad area of contact with the ground, to help prevent slipping on soft, dangerous terrain.14 An elephant normally moves in a lumbering walk at around 6 km (4 miles) per hour, but can charge for short distances at about 35 km (22 miles) per hour. ( See sidenotes below.)

It is clear the elephant is perfectly designed to deal with its bulky frame and weight, and its highly specialised trunk is one of the marvels of the animal kingdom. The elephant today has no known natural predators. This magnificent creature is yet another example of the ingenious design of the Creator.

Elephants don’t run, they charge

The sight of a seven tonne African elephant charging headlong at 35 km (22 miles) per hour would be enough to make anyone’s blood run cold. Olympic records for the 100-metre sprint indicate that man’s top running speed is 36 km (23 miles) per hour, but over a distance of 400 metres this drops to 33 km (21 miles) per hour, and for the 1500 metres event, the cream of the world’s athletes can only manage 24 km (15 miles) per hour.1

Elephants do not ‘run’ in the usual sense of the word. Unlike most animals, at top speed there is very little oscillation of the leg about a pivotal point, and there is no ‘suspended phase’, i.e. a period of free flight when all four feet are off the ground at the same time. Instead, the gait of a charging elephant has two semi-suspended phases: when the two rear legs are off the ground together, and when the two forelegs are off the ground together.2 The maximum forward and backward movement of legs is restricted so that the legs are nearly always under the body.3

References

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, 15th edition, 1992, Macropaedia 28:170–171.

- Haynes, G., Mammoths, Mastodonts, and Elephants, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., 1991, p. 23.

- Ref. 2, p. 11.

Ancestors, selection and Nepalese ‘mammoths’

African and Asian elephants, along with now-extinct species such as the mammoth, stegodon and mastodon, are most likely all descended from the one basic ‘kind’ present on the Ark.1 That ‘elephant’ would have contained all the genetic information for the possible species variation to come as its descendants spread across the globe after the Flood. For example, the potential for both large and small ears was in the genetic information of the basic kind. The ‘culling’ of some of this information by natural selection (plus other factors, such as ‘genetic drift’ —chance loss in small populations) resulted in fixed characteristics within each group — sometimes the result of fine-tuned adaptation to the environment (for example, the larger ears of the African elephant).2 In other words, ‘modern’ elephants contain less genetic information than their ancestors.

Some of this loss of information is still going on. Because poachers keep killing elephants for their tusks, those with a genetic defect losing (or suppressing) the information for tusks are favoured by selection.3 So, as this defect/loss has spread through the population, more and more ‘tuskless’ elephants have ‘evolved’. But this demonstrates a downhill process, the very opposite of the ‘uphill’ process (a net gain of information) needed to turn fish into philosophers (or algae into elephants).

Many people see mammoths, as featured in ‘stone age’ cave paintings, for instance, as part of a world many tens of thousands of years before the present. The biblical truth about history would indicate a time-frame much closer to the present. Thus it was exciting when some huge live elephants were discovered recently in Nepal, which had the same sloping backs and humped heads as the elephants (mammoths) drawn in the cave paintings.4 This would indicate that the genetic information for these features has survived within the modern elephant gene pool, bringing the ‘time of mammoths’ not only much closer to, but right into, the present.

References and notes

- This is not just conveniently assumed for the sake of minimising the numbers of animals on the Ark. Creationists have shown that even if the assumed meaning of ‘kind’ was genus in every case (which would mean that separate pairs of African elephants, Asian elephants, mammoths, stegodons and mastodons would have been taken on board), the Ark could still easily have accommodated them.

See J. Woodmorappe, Noah’s Ark: A Feasibility Study, Institute for Creation Research, El Cajon, CA, USA, p. 6–8, 1996. - Sarfati, J.D., Refuting Evolution, Master Books, Green Forest, AR, USA, Ch. 2, 1999.

- Elephants losing tusks, Creation 20(2):7, 1998.

- Wieland, C., ‘Lost world’ animals —found! Creation 19(1):10–13, 1996. This discovery is now widely recognized, and a video has been made of these creatures in their natural habitat.

Swimmers with snorkels

Elephants have long been known to be excellent swimmers,1 even to the point of using their trunks as breathing snorkels. Now some Australian biologists are promoting the theory that the evolutionary ancestors of elephants spent millions of years as aquatic animals.2 This of course flies in the face of previously ‘certain’ beliefs about ‘elephant evolution’.

Their evidence? Primarily the discovery, in the developing kidneys of elephant fetuses, of funnel-shaped ducts which are also found in the kidneys of frogs and freshwater fish. (Although the Australian biologists promoting this theory distance themselves from Haeckel’s discredited idea of an embryo repeating its evolutionary history,3 their theory appears to be based on exactly the same principles as Haeckel’s theory.)

Of course, once such an idea gains momentum, it is always possible to point to other features consistent with it. Thus, it was put forward for a time (and some evolutionists still believe it) that we evolved from an ‘aquatic ape’. Proponents of this particular ‘just so story’ about ‘human evolution’ could point to things such as our lesser amount of hair compared to apes (for streamlining in the water), the so-called ‘diving reflex’ in the newborn, and more. Those who prefer another story of our ancestry can point to many similar ‘proofs’ that we evolved from an ape on the African savannah. Evidence can always be interpreted in a variety of ways.

There is much evidence consistent with the Bible, which makes it plain that neither elephants nor humans ever went through an ‘aquatic stage’. The difference is that this account is not one invented by fallible human story-tellers, but is recorded for us as the sure testimony of the living God, who made Heaven and Earth.

References

- Merit Students Encyclopaedia 6:313, 1983.

- Gaeth, A.P. et al; Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 96(10):5555-8, May 11, 1999.

- Grigg, R., Ernst Haeckel: Evangelist for evolution and apostle of deceit, Creation 18(2):33–36, 1996; Grigg, R., Fraud rediscovered, Creation 20(2):49-51, 1998.

References and notes

- Haynes, G., Mammoths, Mastodonts, and Elephants, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., 1991, p. 3. Return to text.

- Ref. 1, p. 10. Return to text.

- Ref. 1, p. 41. Return to text.

- The New Encyclopaedia Britannica, 15th Ed., 4:442, and 23:436–437, 1992. Return to text.

- Ref. 1, pp. 121–122. Return to text.

- Ref. 1, p. 40. Return to text.

- For comparison, the longest Asian elephant tusks recorded were 2.7 m, but this was exceptional, because 1.5 m is the more usual upper size limit for Asian elephants. See ref. 1, pp. 44–45. Return to text.

- The New Encyclopaedia Britannica, 15th Ed., 29:535, 1992. Return to text.

- Ref. 1, p. 58. Return to text.

- World Of Wildlife, 2:15. Return to text.

- Ref. 1, p. 59. Return to text.

- Ref. 1, pp. 35–36. Return to text.

- Ref. 1, p. 11. Return to text.

- The New Encyclopaedia Britannica, 15th Ed., 29:21, 1992. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.