Where did the Israelites cross the “Red Sea”?

Background

During their sojourn in Egypt, the Israelites built and lived around Pithom and Raamses (Exodus 1:11). 1 These were cities in Goshen, in the eastern Delta region (figure 1) of Lower Egypt (Genesis 47:6, 11). We can be fairly certain of where they lived. However, the timing of the events immediately after they left Egypt is somewhat murky.

Besides the timing of events, there are questions about what we should see left behind as evidence at any of the proposed crossing points. This was a very long time ago, so the land may have changed, archaeological evidence may be buried, wind-blown sand could have filled in shallow bodies of water or altered the landscape in general (which is very common in Egypt), and siltation and marsh growth may have moved shorelines.

Also, even though the Red Sea crossing was clearly miraculous, physical causes (e.g., a strong wind) are also mentioned. Thus, there is a tension among the scholars about how much ‘miracle’ they want to accept. Did a wind move the water? Then the water must have been quite shallow. But if it was too shallow, the water could not have “stood up like two walls” on either side or drowned the Egyptian army. Wind alone could never part water that is a half-mile deep (for example, at the Gulf of Aqaba). Even steel-reinforced concrete could not hold back that much pressure. If a miracle is involved, we need not search for physical answers, but we still need to exhaust all possibilities.

Tim Mahoney has produced an excellent series of films in the Patterns of Evidence series, including a film on the Exodus and The Moses Controversy . He follows these with a two-part series of films on The Red Sea Miracle (one of which I appeared in). From these, it is clear that there are many potential ‘Red Sea’ crossing points, but scholars have not come to any consensus. Briefly, the Israelites either crossed a bay near the Mediterranean coast, one of the lakes in the Bitter Lakes district, the northern Gulf of Suez, a lake north of the Gulf of Aqaba, northern Aqaba, mid-Aqaba in the area of Nuweiba, or southern Aqaba at the Straits of Tiran.

We can use any standard nautical chart to examine the water depth at any of the crossing sites. I used a free chart viewer (fishing-app.gpsnauticalcharts.com) to zoom in on the various locations. Screen shots will be included below. See figure 2 for an overview of the northern Red Sea region.

Crossing the Red Sea

On the night of the Exodus, 2 the Israelites journeyed from Rameses to a place called Succoth (Exodus 12:37). There are three places by that name in the Bible and the root word might have something to do with animal stables (c.f., Genesis 33:17 and Joshua 13:27).

From Succoth, they went to Etham, “on the edge of the wilderness” (Numbers 33:6), before doubling back to Pi-hahiroth, which was between Migdol and the sea. This was in front of (Exodus 14:2) and to the east of (Numbers 33:7) a place called Baal-zephon. Etham is not very descriptive. It is referred to as a place and as a wilderness. From context, it is also called the Wilderness of Shur and was also immediately on the other side of the crossing point. ‘Migdol’ is not a city. It means ‘fortress’ and, since the Egyptians were very protective of their borders, there was a migdol near most potential crossing sites. 3 Nobody is certain what ‘Pi-hahiroth’ means, as it could have either Hebrew or Egyptian roots. Baal-zephon might have the root word for the main Canaanite god (Baal), but nobody has been able to conclusively locate a site by this name anywhere in the region.

Different scholars have different ideas about the crossing site. Some ideas are better than others, but much of the debate centers on which aspect of the account gets more weight. Is it a timing issue? Then they crossed soon after leaving Goshen. Do the place names drive the discussion? Then perhaps we should focus on Timna, north of Aqaba (see below). Do we require that wind, and only wind, parted the sea? Then any crossing point on the Gulf of Aqaba is necessarily excluded. The question of where to place Mt Sinai also comes into the discussion, and there is much debate on that as well, but that is outside the scope of this article.

All we know for certain is the starting point. Yet, we know they had doubled back (Exodus 14:2) and become trapped between Pharaoh’s army and the sea. At this point, God intervened, giving us one of the most famous historical accounts in the Old Testament:

Then Moses stretched out his hand over the sea, and the LORD drove the sea back by a strong east wind all night and made the sea dry land, and the waters were divided. And the people of Israel went into the midst of the sea on dry ground, the waters being a wall to them on their right hand and on their left. The Egyptians pursued and went in after them into the midst of the sea, all Pharaoh’s horses, his chariots, and his horsemen. 4 And in the morning watch the LORD in the pillar of fire and of cloud looked down on the Egyptian forces and threw the Egyptian forces into a panic, clogging their chariot wheels so that they drove heavily. And the Egyptians said, “Let us flee from before Israel, for the LORD fights for them against the Egyptians.”

Then the LORD said to Moses, “Stretch out your hand over the sea, that the water may come back upon the Egyptians, upon their chariots, and upon their horsemen.” So Moses stretched out his hand over the sea, and the sea returned to its normal course when the morning appeared. And as the Egyptians fled into it, the LORD threw the Egyptians into the midst of the sea. The waters returned and covered the chariots and the horsemen; of all the host of Pharaoh that had followed them into the sea, not one of them remained. But the people of Israel walked on dry ground through the sea, the waters being a wall to them on their right hand and on their left.

After successfully crossing the sea, they then made several more stops before arriving at Mt Sinai:

- Marah (Exodus 15:22–23) in the wilderness of Shur, also called the wilderness of Etham (Numbers 33:8), which was a 3-day journey from the sea (Numbers 33:8)

- Elim (Exodus 15:27; Numbers 33:9)

- “By the Red Sea” (Numbers 33:10), meaning they had travelled along the shore for at least four days.

- The wilderness of Sin (Numbers 33:11). They arrived on the 15 th day of the 2 nd month (Exodus 16:1), or after traveling about 30 days.

- Dophkah (Numbers 33:12)

- Alush (Numbers 33:13)

- Rephidim (Numbers 33:14), where they fought against Amalek (Exodus 17).

- Sinai (Numbers 33:15), arriving on the 3 rd new moon after they left Egypt (Exodus 19:1), or after about 75 days of traveling. Jethro visited Moses at Sinai, traveling from Midian (Exodus 18) with Moses’ family.

When did the crossing occur?

The Red Sea crossing had to happen before the 30 th day, when they arrived at the Wilderness of Sin. But you must allow time to camp at Succoth, Pi-hahiroth (if they camped there overnight prior to the crossing, c.f. Exodus 14:9), Shur, and Elim.

If they only stopped at Succoth and Pi-hahiroth before the crossing, Aqaba is excluded. But it is also possible that the sites listed are only the main stopping points where they spent significant time. The distance between campsites is difficult to determine. Either they sprinted across Sinai (it is something like 350 km/220 miles from Goshen to Nuweiba) and then relaxed in Arabia, or they moved but a few miles per day, then crossed Suez, the Bitter Lakes, or some northern bay.

The only additional geographic clues we have are not very helpful for identifying crossing points: the fight with Amalek (they were associated with the “people of the east” in Judges 6 and 7 but were resident of Ephraim (central Israel, north of Jerusalem) in Judges 12) and the visit of Jethro (Midian was in northern Arabia).

Possible crossing points

Option 1: Northern coastal route

One of the many shallow bays and ponds along the Mediterranean coast could have been the crossing point (figure 3), but this option runs into an immediate textual problem. Exodus plainly states that “God did not lead them by way of the land of the Philistines, although that was near.” (Exodus 13:17)

As they show in the films, computer models have demonstrated that wind “set down” can expose shallow areas if the wind blows strong enough and long enough across some bodies of water. This assumes that the wind, which was definitely mentioned, was the only cause of the water’s parting. It also would not produce a “wall” of water “on the left hand and on the right”, as described in the Exodus account. Also, this entire area would have been much different thousands of years ago. Inshore locations like this simply do not stay the same for long periods of time. Siltation fills in shallow bodies, shorelines migrate, storms can open up new inlets, subsidence due to compacting sediments can cause water to deepen, etc.

Many scholars have pointed out that the phrase translated ‘Red Sea’ in our Bibles ( yam suph ) can also mean reed sea. There are many potential areas that could fit that description. There are several bodies of water in the area called that today and several were called that in ancient times (including Aqaba). Additional ones may have since disappeared under the sands. If that name was not recorded, we would not even know it. Thus, scholars, once again, argue among themselves as to which location is most likely.

Option 2: Bitter Lakes region

To the north of the Gulf of Suez are several shallow, salty lakes (figure 4). What would this area have looked like thousands of years ago? Is it possible the lakes were connected to the Red Sea? This is not necessary because they could have still been called Yam Suph if they were not. Perhaps they were deeper, or maybe a ‘lake’ that existed then has since turned into a field and the crossing point is now buried under land? Several of these lakes dried up when they built the Suez Canal. There are many possibilities here that remain unexplored. Note that one does not need miles-deep water to drown a soldier. All you need is water deeper than a person is tall. Six feet or 6,000; it’s all the same to a drowning person. Note that camping “by the Red Sea” four days after crossing would be difficult if the crossing site was one of these lakes or some northern bay. This would require either doubling back to the relatively small lake or the second “yam suph” would have to be different from the one they crossed. This is not impossible, but it does not seem to be a natural reading of the text. It is possible that this is the same one if, after crossing the Red Sea at Suez (below), they turned south. It would also be possible if they crossed the Gulf of Aqaba at Nuweiba (see below) and turned north, but not if they turned south as the ground is too mountainous.

Option 3: Suez

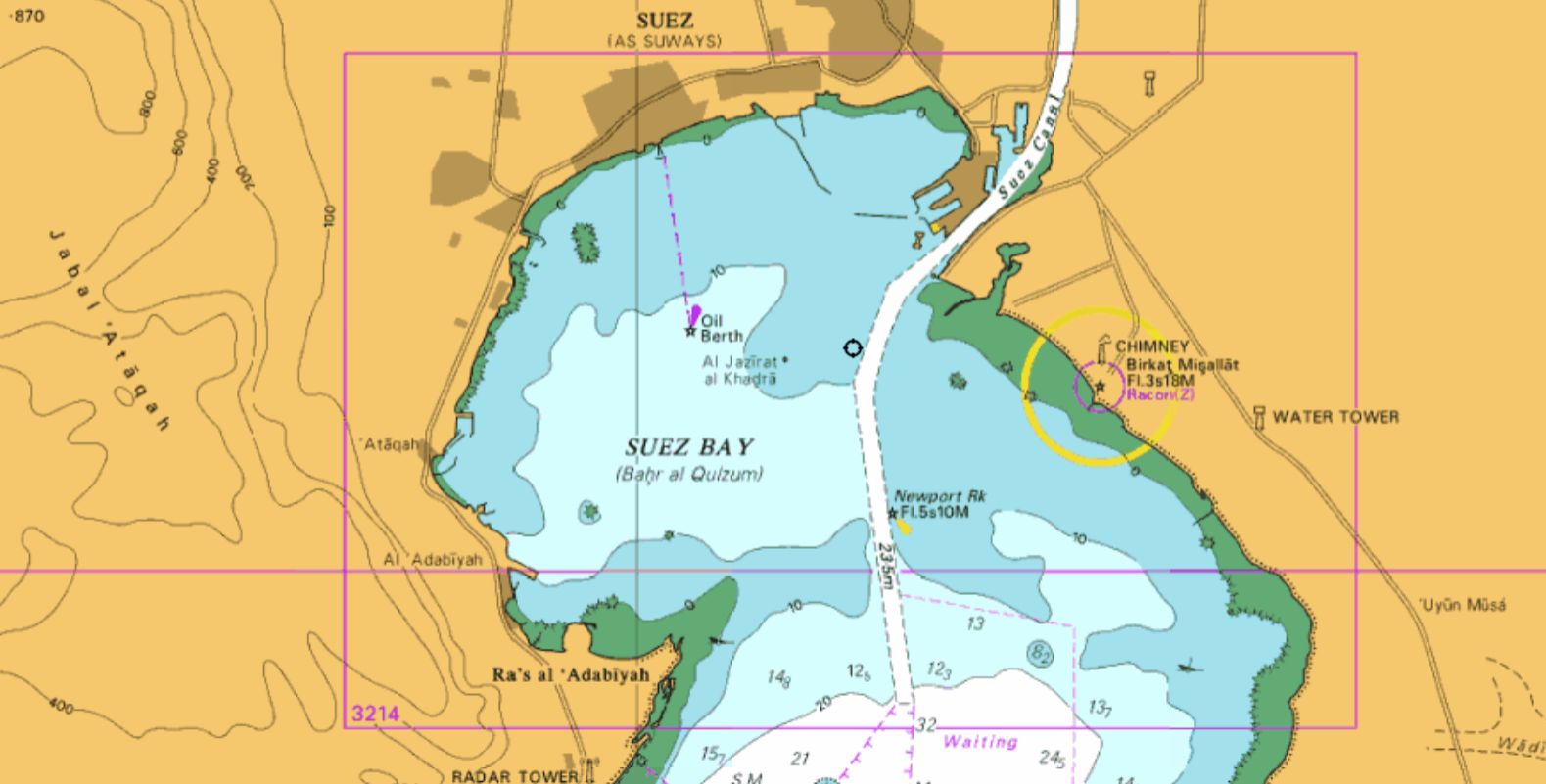

After marching for two days, the Israelites could have made it to the tip of the Gulf of Suez (figure 5). This would also have given enough time for dispatch riders to reach Pharaoh and for him to chase down the Israelites camped on the shore. Among the Red Sea/Reed Sea/Yam Suph crossing options, Suez is the shallowest about 10 m (33 ft) at Adabiya, with a gentle slope. In fact, the entire Gulf of Suez is shallower than the shallowest possible crossing point in the Gulf of Aqaba. Adabiya would be easy to get to from Rameses, and if they went around the western side, they would be “hemmed in” by a mountain to the south. The crossing is only about 9 km (< 6 miles), but there is some contention about what the Egyptians called the land on the other side. Some claim they would still be in “Egypt” if they crossed at Adabiya. Others point out that the forts just east of the delta are the border of Egypt, which is why they had forts there, and the Sinai Peninsula was designated as ‘foreign land’, even though they had mining operations there. If this is the case, the entire Sinai Peninsula was not considered part of Egypt.

Option 4: Aqaba

There are several possible crossing points associated with the Gulf of Aqaba.

Option 4a: Lakes north of Aqaba. Fred Baltz supports this site, at a place called Timna. 5 He claims there are good matches for the names Migdol, Baal-zephon, and Pi-hahiroth here.

Option 4b: Northern Aqaba. There is no real route to get here from the west, there is no place to get trapped along the coast, the sea bottom is steep on the west and the east sides of the gulf and on land there is a steep descent down to the water and up from the water on the Arabian side. Plus, the Israelites could simply have walked around the northern shore.

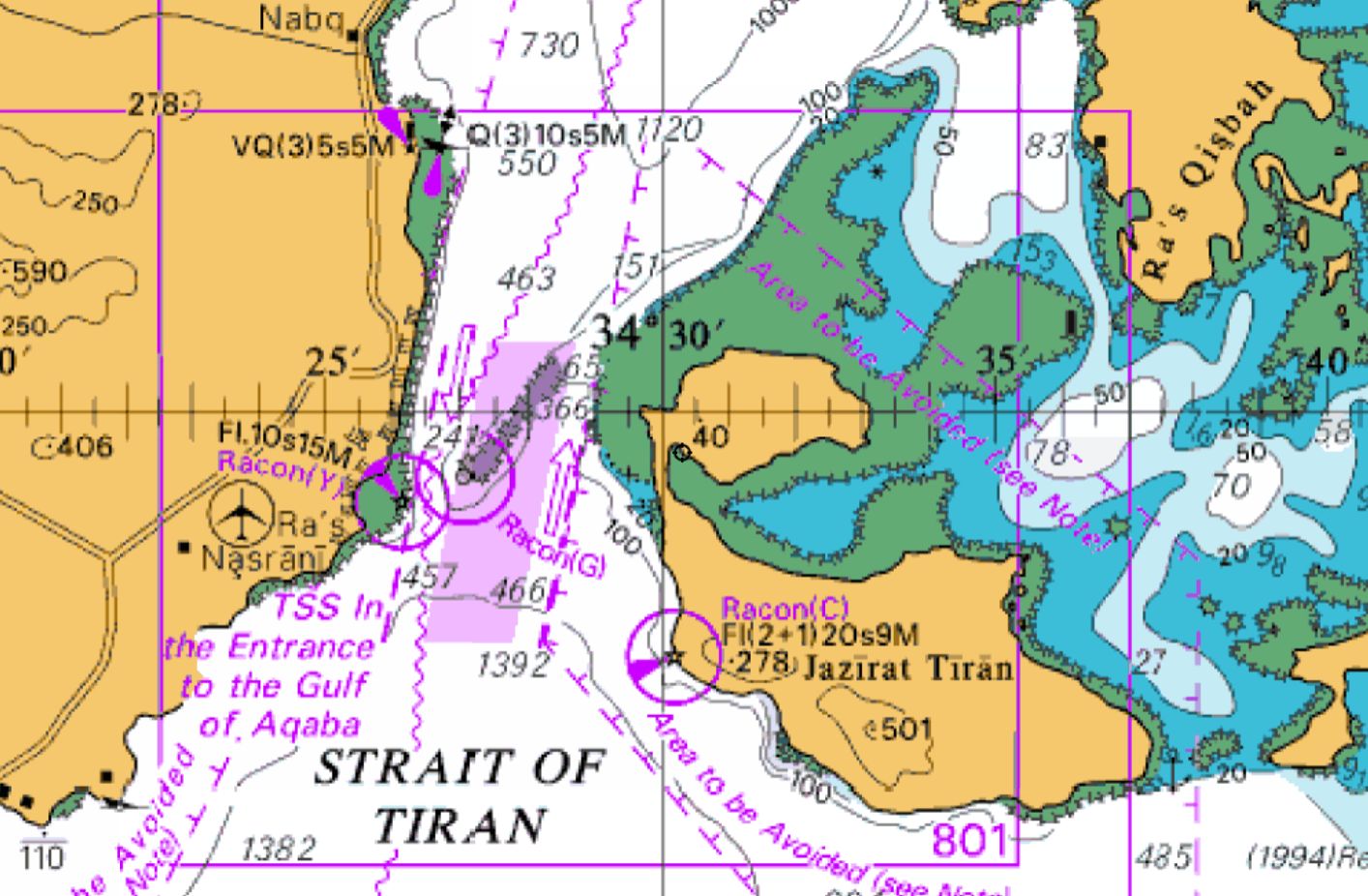

Option 4c: Southern Aqaba/Strait of Tiran (figure 6). This is the shortest possible crossing through Aqaba, but there is an extremely steep ascent followed by massive fields of sharp, irregular, leg-breaking coral heads. It is also the longest possible route from Rameses to a Red Sea crossing point (about 420 km/260 mi). Of course, the coral reef should have grown considerably over the millennia, so we cannot use today’s bathymetry to know what it would have been like thousands of years ago. This entire coral reef had to have grown since the Flood. 6 It could even have grown since the time of Moses. Someone really needs to examine the topography of the ocean bottom beneath the coral layers.

Option 4d: Mid-Aqaba/Nuweiba.

This is the most popular alternative among the public. It was popularized by a controversial amateur archaeologist named Ron Wyatt. Many of his claims are clearly false, 7 but this does not necessarily mean this particular one is wrong.

It is important to note there is no “underwater land bridge” here (figure 7). The shallowest depth is nearly

800 m. Depths surpass 1 km just to the south and reach well over 900 m just to the north of the potential crossing site, so there is something of a saddle here, but it is not shallow. Granted, when we are talking about the miraculous providence of God, anything could be possible, but this site would require a very long walk with a serious change in elevation requiring a steep ascent in their march. This would be difficult for animals, children, and the elderly. Perhaps they made several switchbacks on the ascent, making the slope gentler, but this would make the journey even longer. There is also the problem of several million people (if indeed the population was that large) camping on so small a beach, especially since the delta was most likely much smaller thousands of years ago.

Conclusion: Where was the crossing point?

In the end, each of the potential crossing points has strengths and weaknesses. We would do well not to put too much emphasis on one when the others have not yet been fully studied. The remains of the portion of Pharaoh’s army that pursued the Israelites most likely decomposed or were buried in mud or sand. They could be deep in the Red Sea or under an area that is now dry land (e.g. the steamboat found buried under a field, far from the Missouri River ). They could be anywhere within an area of several hundred square miles, most of which remains unexplored. Nuweiba could be it, but no compelling evidence for this hypothesis has been found and there is little reason to expect such evidence will be found in the shallow areas near the beach, even if the Israelites did see Egyptian bodies near the shore.

We need to beware the ‘ knock-out punch syndrome ’. Rarely in the world of archaeology do we see slam-dunk evidence for the Bible. Good evidence that supports the Bible is there, but most of that is for the later periods. There are many other bits of evidence that are perfectly consistent with the biblical account, but which tell us little on their own. Excitement over poorly detailed theories creates an additional danger, in that rejection of a pet theory can lead to disillusionment. What if, for example, after putting so much emotional effort into Nuweiba, it turns out not to be the crossing point?

Our guide should be the biblical narrative. The Red Sea crossing was, in part, a miracle of God. We don’t need to make it easy for Him by having shallow water or easy crossing sites, and we can’t let deep water or difficult terrain preclude a site from consideration. Water depth is not a problem, but landform approaches to and from the crossing point are still an important consideration, and they need room to set up camp for a lot of people. On the other hand, we simply don’t know where the Israelites went through the sea … yet.

Chariot Wheels in the Red Sea?

Over the past several decades, many sensational reports of ‘wagon wheels’ on ‘the bottom of the Red Sea’ have appeared. Yet, no actual evidence for wagon wheels has actually been found. There are some photos, true, but these are almost certainly of modern metal objects.

None of these look like Egyptian chariot wheels. The main image supplied by Wyatt (Figure B1) looks very much like a modern cast-metal wheel. The Egyptians only had copper or bronze to work with, and they corrode quickly in salt water. Note the solid spokes, as opposed to the double-v-shaped split wood spokes used by the Egyptians. The shadowing suggests a groove ran around the outside, as if this was a pulley wheel, although similar grooves ran around the edges of real Egyptian chariot wheels. Notice how pristine it looks. If it really was discovered in the sea, it was dropped very recently. It does not even have any algal growth. There is every reason to believe this is a total fabrication.

In comparison, we have many contemporary paintings of Egyptian battle chariots . The wheels are thin and light, and the wheels usually have six spokes (figures B2 and B3).

We even have contemporary chariots that have been preserved, such as the ceremonial gold-plated chariot found in King Tut’s tomb (figure B4). Don’t let the gold fool you. This chariot is only covered in a thin layer of gold. A metal chariot would have been much too heavy to be pulled by a team of horses across sand. Within his tomb were six chariots, three that were highly decorated, and three utilitarian models designed for normal use.

There is also a lack of provenance. Who can actually say when and where this photo was taken, and by whom, and if the wheel was actually found where it is pictured? The images are never properly documented. As far as size goes, that wheel that was supposedly found in the Red Sea might be only 6” in diameter, but it is impossible to tell from the image because there is no scale. Marine biologists can sometimes look at something in the background like the size of a sponge, fish, or sea urchin and make an educated guess for the sizes of objects, but the classic ‘chariot wheel’ images give few clues.

Think about it: Egyptian chariot wheels were made of wood, 8 and wood is rapidly destroyed in warm tropical seas (figure B5). There have also been claims of bones and skulls found in the area, but these suffer from the same problems just listed, with the added caveat that bones quickly dissolve and/or get eaten in seawater. Consider what was found on the ocean bottom near the Titanic: dozens of pairs of shoes, still laced up. Tanning leather preserves it. The bodies that were once in the shoes, or at least the owners of the shoes if they had been stored in a bag or a suitcase, have long since disappeared.

Evidence must reach a certain threshold in order to be scientifically acceptable. None of the evidence for ‘chariot wheels’ and such meets that standard. Thus, we do not accept this as evidence as support for the Nuweiba crossing site hypothesis. In a similar way, after many years of writing about the possibility of living dinosaurs, CMI went on record strongly cautioning our readers against the idea. (see Dinosaurs are almost certainly extinct ). Why? Because none of the supposed evidences had ever been verified. Creationists are already held to a double standard by the world. Thus, we need to hold onto the best evidence and put the more debatable matters on the back shelf. Nuweiba might be the crossing site, and there is an ever so slight probability that dinosaurs are still clinging to existence in one or two unexplored places on earth (if those even still exist), but we have no hard evidence for either possibility.

There is also no reason to expect to find ancient wooden and metal artefacts, in shallow water, still exposed on the seabed. Wood decays quickly in salt water, especially tropical waters that are teeming with wood-eating teredo worms (aka shipworms), the effects of which are seen in figure B5. Egyptian chariots were mostly wood, with wooden spokes, wooden wheel rims, and wooden tires that were tied on with straps. They were built for speed and lightness. Even shipwrecks from a few hundred years ago leave behind no wood. Burial in sand helps preserve wood, but even that does not last thousands of years. Even if there were bronze fittings on the chariots, bronze decays rapidly in seawater due to a well-known problem in archaeology called ‘bronze plague’, a chemical reaction with chlorides (i.e., sodium chloride in the seawater). After this much time, nothing should be left besides a few objects made of gold, if there were any to start with.

Only a very small, relatively shallow area around Nuweiba beach has been searched via SCUBA. One of the most famous ‘chariot’ discoveries happened during an emergency rescue dive, where an experienced diver went down to grab a novice diver who was swimming into dangerously deep water. Not only might nitrogen narcosis have been a factor at that depth, but the novice ran out of air, precipitating a rapid emergency ascent and a serious risk of getting the bends. Essentially, everything that is not supposed to happen on a dive did. Unsurprisingly, the team has been unable to locate the coral-encrusted ‘chariot’ again. 9

Corals take on many different shapes as they grow. The shape is dictated by the species normal growth form, the amount of available light, competition from neighboring colonies, and the direction of prevailing currents. Many species will form horizontal plates or circular discs. These can often be seen growing on axle-like knobs or stalks (figure B6). This is true of multiple species of coral that inhabit the Red Sea. This image is not the best representation, but a person looking for things that were the size and shape of chariot wheels and axles can easily find them on many of the world’s coral reefs.

Some claim that the chariot wheels, etc. are no longer there but that the coral has encrusted the original material. There are also problems with this hypothesis:

- With the exception of the fire corals (which are not true corals but calciferous hydrozoans), corals don’t typically encrust objects. In the same way, a tree might envelop something it is growing near, but it does not follow the lines of that object.

- Many corals form boulder-like shapes. They might start off life by attaching to a hard object, but they don’t grow in the shape of a cannon, etc. Instead, they grow on the cannon. Even if a wooden object could last long enough to be encrusted, corals don’t do that.

- Corals will fill in any spaces as they grow. Hence, objects will disappear into the coral. Again, the coral will not take on the shape of the object.

- After 3,500 years, a single coral can grow as large as a tall building. Why would we expect to see corals in the shape or size of Egyptian wagon wheels today?

- The video evidence at Nuweiba beach shows a normal patch-reef-like field of corals. Similar areas can be found around the world. There is nothing there to indicate the corals are growing on the remains of the Egyptian army! The coral colonies all appear to be but a few years to a few tens of years old and they are growing on older material (probably corals that grew for a decade or so and were then killed by being buried by sand or by being hit with a burst of freshwater from the wadi).

- But many corals that grow in the area (specifically some species in genus Acropora ) do take on fan-shaped and disc-shaped growth forms. This is especially true in deeper water where light is scarce. Thus, we would expect to see natural corals that take on the shape of a chariot wheel. They may even have what looks like an ‘axle’, but this is nothing more than the attachment point upon which the coral colony developed.

- The Red Sea is very warm, very salty, and is one of the worst places for the preservation of wood.

Considering the physical description of the Nuweiba site, why would we expect to see remains on the shore? Nuweiba is an accreting, sandy delta (figure B7). How much material has been washed down the wadi over the past 3,500 years? Why would we not expect the remains to have been washed into deep water, or to have been buried (perhaps by hundreds of feet of sand), or to have decayed? Periodic avalanches from the foreslope of the delta would carry material far out into deep water.

And the use of metal detectors is unhelpful in our search. First, Egyptian chariots did not have much metal on them. Second, most of that metal would have long since rusted away. And third, modern trash will overwhelm any ancient signal.

Finally, let us not forget that we need room to fit maybe two million people, with tents and livestock. Consider that in ancient times the beach would have been smaller than it is today, and you can see that Nuweiba faces some major challenges.

References and notes

- If they lived there during Hyksos times, the name by which the Israelites would have known it was Avaris, but it had still other names at different times. If they left in the 18 th Dynasty, it was would have been called Peru-nefer. The use of the latter name (Raamses) in the Bible was probably due to textual updating. See Cosner, L. and Carter, R., The inspiration of Scripture comes in various forms , 10 September 2019. Return to text .

- They left on the night of the 14 th day of Tishri (Passover, Exodus 12:6) which was the first full moon after the first new moon after the vernal equinox. Return to text .

- There were migdols located in many parts of Egypt. Strangely, there is no mention in Scripture that the Israelites encountered any Egyptian garrisons on their journey. There is also no migdol near Nuweiba. Return to text .

- As far as the identity of this pharaoh is concerned, it is important to note that the text does not say Pharaoh himself went into the sea. Also note that only that part of the army that went in the sea died. Egypt’s entire army would not have been present and the men who were there may not have all died. Return to text .

- Baltz, F. Finding Moses’ path through the Sea, patternsofevidence.com/2021/04/09/moses-path-through-the-red-sea/, 9 April 2021. Return to text .

- See Carter, R., Coral: The animal that acts like a plant, but is an active predator, and makes its own rocks for a house , Creation 39 (3):28–31, 2017. Return to text .

- See Arguments we think creationists should NOT use . Return to text .

- Dunn, J., The Chariot in Egyptian Warfare, touregypt.net/featurestories/chariots.htm, undated. Return to text .

- “Pharaoh’s chariots on the seafloor: panel discussion”, Historicalfaithsociety.com (login required). Return to text .

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.