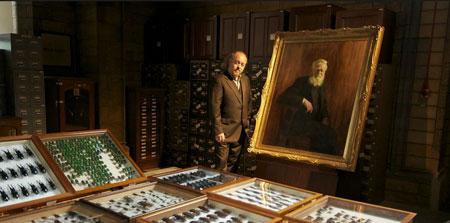

Bill Bailey’s Jungle Hero: Alfred Russel Wallace

To mark the 100th anniversary of the death of English explorer and naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, the BBC has produced a 2-part TV series on his explorations in the islands of Indonesia from 1854 to 1862.1 The presenter is BBC personality Bill Bailey in a serious role, producing and filming the series on location in East Asia. Not surprisingly, the BBC has used the opportunity to give their pro-evolution ‘drum’ a good thump.

Factual Wallace

Most of what the series says about Wallace is factually correct. He did propose that a hypothetical boundary, now known as ‘Wallace’s Line’, existed between the islands of Bali and Lombok, and Borneo and islands to the east, which marks the eastern extent of many Asian animals and the western extent of many Australasian ones.2 It was indeed during a malarial fit on Ternate that Wallace found inspiration for his theory of the origin of species, when it suddenly occurred to him that ‘the fittest would survive’.3 He did write to Darwin in July 1858, setting out this theory in an essay entitled On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart Indefinitely from the Original Type. And Darwin’s friends, Charles Lyell and Joseph Hooker did scheme to achieve a flimsy chronological priority for Darwin by means of a joint reading of papers at the Linnean Society that year, as Bill Bailey shows.

Interestingly, Darwin says in his autobiography: “Another element in the success of the book [Origin of Species] was its moderate size; and this I owe to the appearance of Mr Wallace’s essay; had I published on the scale in which I began to write in 1856, the book would have been four or five times as large as the Origin, and very few would have had the patience to read it.”4

Wallace’s differences from Darwin

BBC promo

What the BBC does not tell viewers is how much Darwin differed from Wallace in their theory of natural selection.5 In an article published in the Quarterly Review of April 1869, Wallace claimed that certain human structures and higher capacities—a large brain, the delicate movements of the hand, sophisticated powers of language—could not have evolved through natural selection, because they conferred no advantage in the lower stages of human development. Savages, he asserted, had no need for them and made no use of them, and yet they were responsible for all of the higher achievements of human culture and civilization. Such features had only emerged, according to Wallace, through the agency of a Power which has guided the action of [natural] laws in definite directions and for special ends. When Darwin read this, he scribbled “No” in the margin, underlined it three times, and added a shower of exclamation marks. In letters to Wallace, Darwin wrote: “I differ grievously from you … . I can see no necessity for calling in an additional & proximate cause in regard to Man.”6 And: “I hope you have not murdered too completely your own and my child.”7

Responding to Darwin, Wallace wrote:

“My opinions on the subject have been modified solely by the consideration of a series of remarkable phenomena, physical & mental, which I have now had every opportunity of fully testing, & which demonstrate the existence of forces & influences not yet recognised by science. This will I know seem to you like some mental hallucination.”8

Darwin was an agnostic and rejected the God of the Bible as the miracle-working Supreme Being. Wallace was a spiritist. His ‘Power’ was not the Creator God of the Bible, but an unidentified ‘higher intelligence’. Wallace had become involved in spiritism and believed that departed souls could communicate through mediums with people still living. In later life he ardently attended séances, where he believed he received messages from dead relatives.

Quite possibly this was a major reason why he did not become a fully accepted member of the Scientific Establishment in Britain, despite the fact that he lectured and wrote widely on scientific subjects, was involved in various social issues such as women’s suffrage, vaccination, and free trade, and was awarded two honorary doctorates.

Meaning of the term ‘natural selection’

Wallace discussed this with Darwin in 1866 (emphases in original):

“This term [survival of the fittest] is the plain expression of the facts,—Nat. selection is a metaphorical expression of it—and to a certain degree indirect & incorrect, since, even personifying Nature, she does not so much select special variations as exterminate the most unfavourable ones. … I find you use the term ‘Natural Selection’ in two senses. 1st for the simple preservation of favourable & rejection of unfavourable variations, in which case it is equivalent to ‘survival of the fittest’,—or 2nd for the effect or change produced by this preservation … .”9

In reply, Darwin said: “Your criticism on the double sense in which I have used Natural Selection is new to me and unanswerable; but my blunder has done no harm, for I do not believe that any one, excepting you has ever observed it.”10

Notice Wallace’s correct understanding of the term ‘natural selection’—not selection of special variations, but extermination of the most unfavourable ones, i.e. not a creating mechanism, but a culling one, or ‘natural rejection’! Notice too, Darwin’s acknowledgment that Wallace’s point was unanswerable. And also that Wallace identified Darwin’s equivocation in using ‘natural selection’ to mean two different things—an observable process and the hypothetical effect. Evolutionists use similar ‘bait-and-switch’ trickery today in defining evolution as change (observable) but also the conjectural idea that microbes changed into mankind.

References and notes

- Broadcast on BBC Two on 21 and 28 April 2013, and in Australia on Nov. 27 and Dec. 4 2013. Return to text.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica 12:469, 1992. Return to text.

- Wallace, A., My Life, Chapman and Hall, London, 1:361–63, 1905. Return to text.

- Darwin C., The Autobiography of Charles Darwin 1809–1882 With original omissions restored Edited with Appendix and Notes by his granddaughter Nora Barlow, Collins, London, 1958, p. 124. Return to text.

- The following section is based on the Darwin Correspondence Project: The correspondence of Charles Darwin, volume 17:1869. Return to text.

- Letter from Darwin to Wallace, 14 April, 1869. Return to text.

- Letter from Darwin to Wallace, March 1869. Return to text.

- Letter from Wallace to Darwin, 18 April 1869. Return to text.

- Darwin Correspondence Project, Letter 5140—Wallace to Darwin, 2 July 1866. Return to text.

- Darwin Correspondence Project, Letter 5145—Darwin to Wallace, 5 July 1866. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.