Journal of Creation 35(2):53–60, August 2021

Browse our latest digital issue Subscribe

Dread of man: part 1—hermeneutics, cultural evolution, and biblical history

Traditionally, God’s words about the fear and dread of mankind (Genesis 9:2) have been seen as descriptive of the postdiluvian world rather than prescriptive. However, the eating of all kinds of animals was sanctioned immediately afterwards (Genesis 9:3). I advance the thesis that both statements are closely connected, that the ‘dread of man’ actually represented a second major biological juncture in history, akin to, though less obvious than, the corruption of animals arising from the Curse. In other words, God supernaturally altered animal psychology when lifting the bar against humans eating meat (Genesis 1:28). Part 1 of this paper begins to explore this proposal, including an overview of the thoughts of previous Bible commentators on these verses. Anticipated objections are explored and answered comprehensively. Part 2 explores the ramifications in much more detail.

In this and a succeeding article we will consider the importance of God’s words to the eight survivors of the worldwide Flood, shortly after they had come out of the Ark (Genesis 8:16):

“The fear of you and the dread of you shall be upon every beast of the earth and upon every bird of the heavens, upon everything that creeps on the ground and all the fish of the sea. Into your hand they are delivered. Every moving thing that lives shall be food for you. And as I gave you the green plants, I give you everything [emphasis added]” (Genesis 9:2–3).

I will propose that the full significance of these verses has been missed by Bible commentators and biblical creationists. The ‘dread of man’ likely represents a supernatural intervention which forever altered animal psychology. These instructions were given to Noah and his family, and by extension, to all human beings. They have fascinating implications for aspects of ethology but especially for human history. God’s decree made a substantial difference to the post-Flood behaviour of terrestrial and marine creatures. It is also crucial for a full appreciation of the origin of hunting, and more besides.

In part 1 of this study, we will first briefly review the perspectives of some important evangelical commentators on Genesis, including those with a commitment to biblical creationism. This will fall short of a comprehensive treatment of the subject, as requiring a dedicated paper in itself.

Next, we will contrast biblical and secular anthropology regarding the procurement of food. Historical records indicate that the ancients were agriculturalists. Nevertheless, long-entrenched evolutionary anthropology avers that farming is a late invention, antedated by a hunter-gatherer subsistence for hundreds of thousands of years. On the other hand, a plain reading of Genesis depicts the Edenic state as one of perfect harmony between people and animals, and a vegetarian diet for all of them. The centuries of corruption following the Fall and Curse drastically altered that, eventually culminating in the Flood judgement of rebellious mankind.

We will also review how Genesis describes the antediluvian world as filled with violence and murder. The fossil record confirms that this included animal violence and carnivory. Moreover, some people brought animal sacrifices to God, yet the Bible is silent as to the consumption of meat by human beings during that period. Not until Noah’s family leave the Ark does God specifically sanction the eating of animals, while simultaneously informing them that every kind of creature would thereafter fear and dread human beings (Genesis 9:2). I will argue that this speaks of a biological juncture. God’s radical intervention changed animal psychology (thus aspects of animal neurobiology) from that point onwards.

Some readers may be suspicious of what they deem a novel, even gratuitous, interpretation of Scripture. Therefore, we will conclude part 1 of this study by answering objections, real or anticipated. Can this thesis be maintained in light of various biblical and scientific considerations?

In the following paper, the implications of this thesis will be opened up in more detail. What is the biological basis for fear? How did the Noahic family fare immediately after leaving the Ark, in terms of procuring food? What of the violence of the pre-Flood (Genesis 6:11) and post-Flood periods? We will consider the advent of hunting, the significance of Nimrod (Genesis 10), dietary issues, even the advent of gardening. Seeing Genesis 9:2 as a divine intervention biologically has a number of interesting implications. It also further highlights the incompatibility of Scripture with the prevailing evolutionary worldview.

Expository thoughts by Bible scholars

In reviewing many evangelical commentaries, I was unable to find any that approached Genesis 9:2–3 in line with the thesis put forward here. The Hebrew words ‘fear’ and ‘dread’ convey the idea of animals being in terror of human beings, but why would this be (see figure 1)?1 Some have seen this merely as a restatement of mankind’s dominion over the creatures, which had been frustrated by the Fall. Basil Atkinson (1895–1971) was of this view, onetime Under-Librarian and Keeper of Manuscripts at Cambridge (UK). He (over)spiritualized the ‘dread of man’ and had nothing to say about the actual post-Flood world:

“In the spiritual sphere, the child of God, armed with the Gospel, is given dominion over every beast, the savage governments and fierce intolerant individuals in the world, over every fowl, all the opponents of the Gospel, over all that moveth upon the earth, earth-born men of worldly interests, and upon all the fishes, creatures not affected by the flood, those standing outside the stream of revelation in ignorance of the covenants, the teeming millions of heathen, spread over the world [emphases in original].”2

Entirely bypassing the historical nature of God’s words, he instead equated this ‘renewal’ of man’s dominion with “the preaching of the Word and the proclamation of the Gospel”.2 Similarly, contemporary British Old Testament scholar and evangelical commentator Gordon Wenham (1943– ) believes God was not speaking of the post-Flood situation at all. He writes that Genesis 9:2 “seems more likely to reflect the animosity between man and the animal world that followed the fall … .”3

However, most commentators acknowledge that Genesis 9:2–3 looks forward. American Professor of Old Testament John Currid (1951– ) writes, “now mankind is allowed to be carnivorous and not merely vegetarian”. He goes on to say, “In addition, the apparently harmonious order between animals and humanity that existed prior to the Fall will no longer hold; instead, the animals will dread mankind.”4 One wonders if he intended to write, “prior to the Flood”. Victor Hamilton (1941– ) is a retired Canadian/American Professor of Old Testament and Theology. He also teaches an explicit discontinuity between the antediluvian and post-diluvian worlds:

“Not all the pre-Flood relationships will be restored. … Human exploitation of animal life is here set within the context of a post-Flood, deteriorated situation.”5

As with the other writers already quoted, however, his discussion extends no further. Renowned biblical creationist Henry M. Morris (1918–2006) tentatively contrasted the ‘dread of man’ to mankind’s original dominion (Genesis 1:28). Yet he noted that the world would ultimately remain under the sway of Satan (citing 1 John 5:19), even after the Flood:

“Thus, man no longer was to exercise direct authority over the animal creation, as had apparently once been his prerogative, rather, there was to be fear manifest by animals, rather than obedience and understanding. … They were delivered into man’s hand, in the sense that he was free to do as he would with them, though, of course, always as a responsible steward under God’s jurisdiction [emphasis in original].”6

And, surprisingly perhaps, Morris had little more to say on the subject. German Hebraist and theologian Franz Delitzsch (1813–1890) commented similarly:

“The dominion of man over the animals has no longer its original and inoffensive character … he must now bring them into subjection by exerting himself to make them serviceable.”7

Delitzsch thought God was simply informing people that they would now have the upper hand: “Into your hand they [will now be] delivered.” However, they would have to work hard to subjugate the animals. This was now to include the eating of animal flesh because the comparative fertility of the pre-Flood world was no more.

A related, but rather more developed, concept is that God was explaining what the natural order of things was going to be like in the post-Flood world. Renowned Old Testament scholar Herbert Carl Leupold (1891–1972) was of this opinion. Accepting that God was intervening in some way, he believed this was solely for man’s benefit:

“There was really need of some such regulation. The beasts, by their great numbers, as well as because of their more rapid propagation, and in many instances also because of their superior strength would soon have gotten the upper hand over man and exterminated him. God, therefore, makes a natural ‘fear’, even a ‘terror’, to dwell in their hearts. Even the birds, at least the stronger among them, need such restraint.”8

Furthermore, he says of God’s statement in Genesis 9:2:

“The truth of the fulfillment of this word lies in the fact that wild beasts consistently shun the haunts of men, except when driven by hunger. No matter how strong they may be, they dread man’s presence, yes, are for the most part actually filled with ‘terror’ at the approach of man.”8

Undoubtedly Leupold’s insights are correct. Other writers have also seen the ‘dread of man’ as God’s gracious protection from the predations of animals, notably Matthew Henry (1662–1714), the English pastor whose six-volume commentary of the whole Bible is still in print today. Henry says:

“Those creatures that are any way hurtful to us are restrained, so that, though now and then man may be hurt by some of them, they do not combine together to rise up in rebellions against man… What is it that keeps wolves out of our towns, and lions out of our streets, and confines them to the wilderness, but this fear and dread?”9

However, acknowledging the useful wisdom put forward by such esteemed writers, I suggest there is more to the story. The divine injunction of “the fear and the dread” of man conveys that any confidence animals had until that point in history was thereafter shattered. While surely this has protected people from dangerous animals ever since, arguably there was a greater need for the animals themselves to be shielded from the excesses of man.

It seems surprising that few commentators have explicitly linked the forecast ‘dread of man’ with what immediately follows, namely the lifting of the ban on meat-eating. Animals obviously feared their animal predators in antediluvian times, as they do now; it was a matter either of fighting (in defence) or fleeing. If humans were frequently killing animals for food before the Flood, one would think they would have learnt to fear people, yet Scripture indicates that they lacked such fear. Today, over four millennia since the Flood, our experience that animals generally steer well clear of human beings tallies with what we read in Genesis 9:2, as the likes of Henry and Leupold observed.

Farming and finding food

It is seldom appreciated that biblical and secular anthropology sharply contrast when it comes to human dietary origins, the history of food procurement, the type of food eaten, and so on (see also part 2). Few of us can readily appreciate the investment of time and effort on the part of our ancestors, in order to acquire a sufficiently nutritious diet.

Before the advent of intensive agriculture and largescale monoculture practices, obtaining the next meal was not simply a matter of visiting the supermarket. For several millennia of human history, much of the population had to work the land. The economies of peoples of antiquity were farming-based. This was true of ancient Egypt, for example; moreover, labourers’ wages were paid in staples such as bread and beer because the first coins were not minted until around 500 BC.10

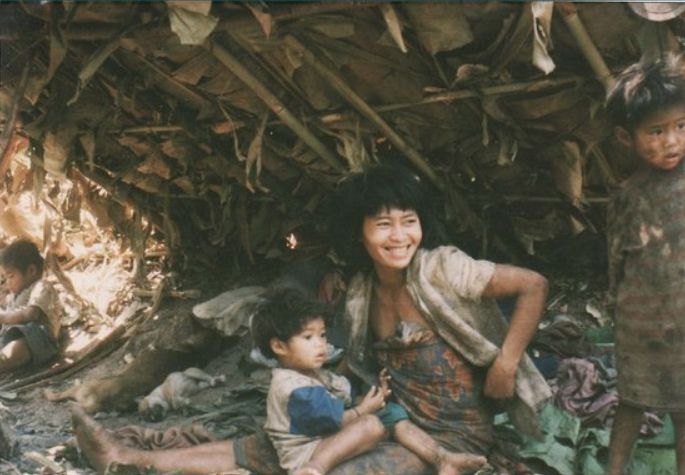

Of course, they could hunt or fish for food—assuming a steady supply of wild animals, as well as the necessary skills and equipment to kill them. Scavenging what was left of predator-kills was another option. Or they could also spend considerable time foraging for wild plants (various fruits, roots, and tubers11), and other natural resources like honey. Hunter-gatherer tribes still exist today, such as the Mlabri people of parts of Thailand and Laos (figure 2).12 But hunter-gathering has never been sufficient to support large populations.13 It has almost always involved a nomadic lifestyle as the people sought out suitable prey animals.

Ideas of cultural evolution

There is a strong tendency for western people to view hunter-gathering as a ‘primitive’ lifestyle. For example, some have described the aforementioned Mlabri folk as a “Stone Age tribe”,14 a description that is clearly based upon evolutionary assumptions. The standard thinking among anthropologists has long been that agriculture is a relatively recent innovation. Allegedly, humans were all hunter-gatherers until 12,000–10,000 years ago. This was the time of the so-called Neolithic Revolution, when people started to settle down and farm the land in earnest.15

Within this mindset, human ancestors had previously existed for hundreds of thousands of years during the Palaeolithic era (aka Old Stone Age). During that entire period, evolutionists insist, there was no cultivation of the land for food. American cultural anthropologist Carol Ember, of Yale University’s Human Relations Area Files, Inc., writes:

“The hunter-gatherer way of life is of major interest to anthropologists because dependence on wild food resources was the way humans acquired food for the vast stretch of human history.”16

If evolutionists are correct, the majority of human history—sometimes dubbed ‘technological prehistory’—took place in the Palaeolithic. This is not an inconsequential point of contention for, as the co-authors of a recent book allege, it was:

“… the period during which we became who we are and began to realise our species’ potential physically, socially, technologically, and linguistically. Examining this period helps provide answers to the fundamental question of what it means to be human [emphases added].”17

In this view, more than 99% of anthropological history predates our earliest written records. Worse, the assertion that our humanness gradually developed over deep time is diametrically opposed to the teaching of Scripture. Andrew Kulikovsky justly censures such teaching as a “secular and materialistic origin story intended to replace religious origin stories—especially the biblical creation account.”18

Altered human diet and animal psychology

In the world before Adam’s Fall, God intended that all human beings and terrestrial animals (“everything that has the breath of life”) should be herbivorous, and we read that “it was so” (Genesis 1:29–30). Killing animals to consume their flesh was clearly off-limits. None of the animals to which God refers were originally carnivores. There was no death of nephesh chayyāh animals before the Fall.19 Scripture is unambiguous about this, in spite of attempts by theistic evolutionists and ‘old-Earth creationists’ to assert otherwise.20 Therefore, in the following centuries, and right up to the Flood, obedient humans were strictly vegetarian.21

But in the post-Flood world today, biblically speaking, a vegetarian diet is no longer obligatory. Most of us supplement our diet with meat, and the Bible explains this. Firstly, the sinful rebellion of Adam and Eve led to the whole created order being cursed (Genesis 3). The Edenic perfection having been shattered, corruption and death ensued. (Whether some antediluvians took to meat-eating is a matter we will consider shortly.) Secondly, nearly 17 centuries later, following the global judgment of the Deluge, God gave new instructions to the Ark survivors, as quoted at the head of this paper. The eating of animals was now expressly permitted (see figure 3). Indeed, the Genesis text indicates that meat-eating would have been a dietary necessity (discussed in part 2) for the early generations of people living in that immediate post-Flood world: “Every moving thing that lives shall be food for you. And as I gave you the green plants, I give you everything [emphasis added]” (Genesis 9:3).

However, just prior to this instruction, God had informed the favoured family of Noah of a revolutionary change to the animals themselves: “The fear of you and the dread of you shall be upon [every sort of animal]” (Genesis 9:2; my emphasis). The future tense, “shall be”, is used in both Genesis 9:2 and 9:3. God was emphasizing a discontinuity between mankind’s former vegetarian diet and the meat-rich diet which was to characterize their post-Flood existence; this is clear from God’s own words, “[just] as I gave you the green plants”. But first He informed them of a behavioural discontinuity regarding the relationship between humans and animals; in effect, ‘the animals shall fear you from this day forward’.

From a plain reading of the text, the ‘dread of man’ seems to entail a radical alteration to animal sensibilities, a hiatus in their centuries-long perception of the benignity of humans. Having lacked suspicion of man before the Flood, they would now view humans with great anxiety and alarm. To argue that God was simply informing people that animals would tend to behave differently post-Flood is surely too prosaic. On the contrary, I believe Scripture is indicating that God supernaturally adjusted the minds of all types of animals—a wholesale psychological and biological transformation.

In part 2, we will see that this divine intervention was necessary to diminish the risks of extinction (especially in the early years after the Ark disembarkation), so conserving animal diversity. However, before discussing these and other ramifications, several qualifications must be made and potential objections faced.

Answering objections

The proposal that God supernaturally imposed the ‘dread of man’ upon animals will likely seem uncontroversial to some readers, even intuitive perhaps. However, previous commentators on Genesis have not mentioned this possibility, seemingly because it did not occur to them. Perhaps, however, some have considered it but summarily dismissed it as unworkable. It is fruitful to anticipate, and answer, possible objections.

Antediluvian meat-eating surely widespread

Surely, some may argue, meat-eating in the period between the Fall and the Flood would have been commonplace? After all, the Bible is emphatic regarding the overflow of wickedness and the outright rebellion of the antediluvians (Genesis 6:5, 11, 12). That being so, is it not likely that some (many) would have engaged in meat-eating, contrary to God’s mandate (Genesis 1:29–30)? And if so, should we concede that even God-fearing people ate meat after the Fall? Would this not have been especially likely after the institution of regular sacrifices, the aroma of burnt offerings whetting appetites?

After all, when God rejected the fig-leaf coverings which Adam and Eve had made for themselves (compare Genesis 3:7 to 3:21), He provided them with skin garments to cover their nakedness and shame. This obviously required shedding the blood of one or more innocent animals. Thus it represented the institution of atoning sacrifice.

By way of an initial answer, whatever one might surmise we must acknowledge that Scripture is silent about any meat-eating taking place in the antediluvian period. There is no hint that, as “men began to call on the name of the Lord” (Genesis 4:26) in those early centuries of history, including making burnt offerings, some human beings began to eat meat. Nevertheless, the majority of people find roasted meat delicious and pleasurable. Is it not likely, then, that the delightful aroma of sacrificial burnt offerings would have eventually led to the great majority of rebellious humans ignoring God’s original mandate? If so, does this not weaken the force of the thesis, that the ‘dread of man’ (Genesis 9:2) was imposed to offset the greatly increased threat to animal survival with God’s sanction of meat-eating (9:3)?

Clearly, we cannot possibly know how prevalent meat-eating was during that period. Some, perhaps many, may have done so. But is it actually so obvious that people then would have perceived meat-eating just as we do now? Even today, a significant minority of people are vegetarian, for a variety of reasons. One can legitimately ask whether the odour of roasting animal flesh would have been pleasing to people who had never eaten meat. Certainly, a number of vegetarians testify to having a strong antipathy for it. Not all vegetarians secretly crave meat! Also, the agreeable anticipation that most people experience upon smelling meat cooking may well be something learned. The person who has never tasted meat likely finds the aroma of steak much less enticing than do seasoned carnivores!

Moreover, a burnt offering was just that; the meat was not being ‘cooked to perfection’ but burnt up. Most people, whatever their dietary preferences, deem the smell of burning flesh to be very unpleasant. The entire animal was involved in a burnt offering; e.g. “the whole ram” (Exodus 29:18; Leviticus 8:21). This would have included the internal organs, skin, and wool. Medical professionals who use electrocautery22 to remove unwanted skin growths and cancerous tissue, to cauterize skin lesions (thus sealing blood vessels), or to create incisions, find the smell very disagreeable. And everyone dislikes the fetid odour of burning hair, caused by the release of volatile sulfur compounds upon the thermal decomposition of its keratin protein.

That sacrifices offered by antediluvians would have taken the form of a “burnt offering” seems clear from Genesis 8:20, where Noah (who lived 600 years before the Flood) performs this very thing (figure 4). Long before the Mosaic Law, people were bringing sacrifices of burnt offering to God. A famous example is Abraham (Genesis 22:7–8, 13). God later instructed Moses, shortly after the giving of the Ten Commandments, that the people should bring “burnt offerings” (Exodus 20:24). While this came to be part of a much more rigorous institution of animal sacrifice than previously, the concept was not new. Then, of course, the rest of Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers (and to a lesser extent Deuteronomy) are replete with references to burnt offerings. It was not cooking but burning; the flesh and entrails were consumed by the fire (e.g. Exodus 29:13).

Possibly, it might be objected that the Bible teaches otherwise. For example, “And the priest shall burn all of it on the altar, as a burnt offering, a food offering with a pleasing aroma to the LORD” (Leviticus 1:9). However, this is not evidence that the sacrifices would have gotten human stomach juices flowing. Rather, the “pleasing aroma” is explicitly said to be for God’s benefit (and also in numerous other verses). It is figurative language, conveying that God is pleased to accept this sacrifice on behalf of the people. It is certainly not indicating that He is pleased with the odour of burning flesh!

Before moving on from this objection, one naturally assumes that Adam passed on the critical teaching concerning atoning blood sacrifice (Genesis 3:21) to his sons, for Abel knew this to be the acceptable way of approaching the Lord. Unlike his brother Cain, he brought “fat portions” of the firstborn animals of his flock (Genesis 4:4). Jesus even identifies Abel as a prophet, slain by his jealous brother (Luke 11:50–51). But there is nothing in Genesis to imply that people were holding back some of the meat for food. To maintain this view, one must read back into the text what we know of the provision for priests under the Mosaic Law (e.g. Exodus 29:27; Leviticus 7:31–35). We read of no divinely appointed priestly class before the Flood.

Instead, God’s bar on meat-eating (Genesis 1:29–30) clearly remained in place right up to the time of the Flood. This is why He specifically addresses this very question in Genesis 9:3. God-fearing people would have shunned meat-eating. I suggest that it weakens the force of Genesis 9:3 if we suppose that most of the antediluvian people were already eating meat.

Not all animals fear humans

We are familiar with the fact that all sorts of wild animals generally give human beings a wide berth; and sometimes appear to be genuinely terrified of them.23 Certain species are so shy and elusive that it is rare even to glimpse them. To snap an image or video footage of such a creature is newsworthy, as with a snow leopard caught on camera in 2014.24 But if the ‘dread of man’ really was a divine imposition upon animals, why are there notable exceptions, such as reported cases where animals are fearless?

Records of explorers from recent history furnish examples of creatures which, for this very reason, were vulnerable to hunting and extinction. The dodo is a classic example—a flightless bird, endemic to Mauritius, driven to extinction by the late 17th century.

Another interesting example was recorded a century and a half later when English explorers, led by Captain Matthew Flinders (1774–1814), first landed on Kangaroo Island (South Australia). This island had not been inhabited by indigenous people and the kangaroos were initially unafraid of man, so much so that the ship’s cooks were able to walk right up to them and club them to death. Flinders wrote, “In gratitude for so seasonable a supply [of kangaroo meat], I named this southern land KANGUROO ISLAND.”25 The tameness of animals of the Galápagos Islands is also well-known and will be explored more fully in part 2 of this paper.

These are fascinating cases. Yet a supernaturally induced ‘dread of man’ in Noah’s 601st year does not rule out possible exceptions, especially so long afterwards. Genesis itself mentions the special case of domesticated animals, variously translated as “cattle” (KJV, NKJV, RSV) or “livestock” (ESV, NIV, NASB, NLT). These feature at creation (Genesis 1:24–26; 2:20), the Fall (Genesis 3:14), during the Flood (Genesis 7:14, 21; 8:1), and just after the Flood. Domestic animals are mentioned after God’s words about the ‘dread of man’ (Genesis 9:10).

Also, certain species of zoo animals may become so accustomed to human contact that they exhibit little or no fear.26 The same is true for certain animals which visit deliberately provided feeders near our homes (e.g. foxes, racoons, squirrels, and all manner of birds). At times of food scarcity or drought, desperate animals overcome their natural fear and may deliberately seek human help.

We know that “every kind of beast and bird, of reptile and sea creature, can be tamed and has been tamed by mankind” (James 3:7); but the word ‘tame’ is itself an indication that the wild state is the norm (figure 5). These exceptions to the rule are noteworthy precisely because a lack of fear in animals is unusual. (The biological basis of fear is discussed in part 2.) And several millennia on from the Noahic Flood, it is hardly surprising to find more exceptions, but they are anomalies. Possibly, the ‘dread of man’, albeit supernaturally imposed, had first to be ‘triggered’ in some instances. If so, it might explain occasional ‘aberrations’ of unusually tame wild animals to this very day.27

Man is only one predator of many

After the Fall, various animals surely began to attack and kill other animals. This would have been rampant for many centuries before the Flood. Surely, therefore, fight-or-flight behaviours were already in place, and prey animals would have learned to hide and flee from their predators? If so, is this not a strong counterargument to the thesis that the ‘dread of man’ was supernaturally ordained?

Firstly, we must insist that the fossil record (largely a record of antediluvian life forms) unambiguously bears witness to the fact that attack and defence structures were employed by creatures from the earliest post-Fall times.28 Thus, there were predators and prey. Among the fossils we find abundant evidence of tooth marks, bone puncture wounds, stomach contents, and coprolites (fossil dung) of carnivores incorporating animal remains. Secondly, it therefore follows that animals would have had essentially the same fight-or-flight responses that they have today. In other words, “an acute threat to survival that is marked by physical changes, including nervous and endocrine changes, that prepare a human or an animal to react or to retreat.”29 Fight and flight mechanisms are sophisticated and well-designed. They were created in the foreknowledge of God to help creatures survive in the post-Fall, cursed environment. As such, all these things would have been present before God’s imposition of the ‘dread of man’.

However, none of the foregoing negates that the ‘dread of man’ was a supernatural intervention at the end of the Flood. It was not “the fear and dread” of other animals which God said would be upon all beasts, birds, creeping things, and fish. Rather it was “the fear and dread of you [human beings]” (Genesis 9:2).

Nearly 1,700 years earlier, the Curse had also involved wholesale biological alterations to all living organisms—a point which is not controversial among biblical creationists. Genesis 3:14 says the serpent was cursed “above all livestock and above all beasts of the field”; that is, all were cursed. The Apostle Paul emphasizes this in teaching that the entire creation has been “groaning” ever since God subjected it to the “bondage to corruption” (Romans 8:20–22). Some of those changes would not have been especially obvious from physical appearances, rather behaviourally. In other cases, the changes to the appearance and/or behaviour of animals resulting from the Curse would have been more dramatic.

So yes, in the centuries between the Fall and the Flood, there was much animal violence, predation and carnivory, for which the fossil record furnishes plenty of evidence. Living creatures knew when to flee from other animal predators, but the biblical record strongly indicates that they did not take flight from man. To argue otherwise is to neutralize the force of God’s words. Consider this comparison:

- “Cursed is the ground because of you; … thorns and thistles it shall bring forth …” (Genesis 3:17–18).

- “The fear and dread of you shall be upon every [type of living creature]” (Genesis 9:2).

In stark contradiction to theistic evolution and ‘old-earth’ compromise positions, biblical creationists insist that prickly, spiny plants were not yet present in creation when God spoke those words to Adam. By the same logic, when God spoke to Noah’s family after the Flood, animals had not yet feared people.

Conclusion

Following the creation (Genesis 1–2), the Curse was the first great biological juncture in world history, and must have followed quite soon after the completion of creation.30 The world did not simply go haywire because of human sin. Rather God deliberately subjected it to its state of futility (Romans 8:20). I have proposed that the ‘dread of man’ represents a second biological juncture in world history. Although imperceptible as far as the physical appearance of the animals was concerned, its impact on their psychology was radical. I maintain that Genesis 9:2 speaks of a supernatural intervention. It is closely linked to God’s mandate that, thereafter, every kind of animal would be potential food for mankind (Genesis 9:2–3). God Himself highlights the specific and stark contrast between this and His original command regarding a vegetarian diet (Genesis 1:29).

Various objections to this view have been anticipated and answered. Aside from the question of whether some antediluvians ate meat (or to what extent), there is certainly little sport in slaughtering animals which do not turn and flee. And it is interesting that hunting is not mentioned in the Bible until Genesis 10 (see part 2). While some biblical creationists may deem this thesis an unwarranted, even hyper-literal, application of Genesis 9:2–3, it is biblically faithful. Furthermore, there are several important implications, which will be explored in part 2.

References and notes

- For a fuller discussion: Sarfati, J.D., The Genesis Account: A theological, historical, and scientific commentary on Genesis 1–11, Creation Book Publishers, Power Springs, GA, p. 596, 2015. Return to text.

- Atkinson, B.F.C., The Pocket Commentary of the Bible: The book of Genesis, Henry E. Walter Ltd., Worthing & London, UK, p. 91, 1954. Return to text.

- Wenham, G.J., World Biblical Commentary: Genesis 1–15, Zondervan, Grand Rapids, MI, p. 192, 1987. Return to text.

- Currid, J.D., Genesis 1:1–25:18; in: A Study Commentary on Genesis, vol. 1, EP Books, Leyland, England, p. 216, 2003. Return to text.

- Hamilton, V.P., The Book of Genesis Chapters 1–17, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., Grand Rapids, MI, pp. 313–314, 1990. Return to text.

- Morris, H.M., The Genesis Record: A scientific and devotional commentary on the book of beginnings, Baker Book House, Grand Rapids, MI, p. 223, 1976. Return to text.

- Delitzsch, F., A New Commentary on Genesis, vol. 1 (translated by Taylor, S.), T. & T. Clark, Edinburgh, UK, p. 283, 1899. Return to text.

- Leupold, H.C., Exposition of Genesis, Evangelical Press, London, p. 329, 1972; first published by Wartburg Press, 1942. Return to text.

- Matthew Henry’s Commentary, vol. 1: Genesis to Deuteronomy, Hendrickson Publishers, Peabody, MA, p. 56, 1991. Return to text.

- See: ‘The birth of, and reasons for, coinage in Egypt’, p. 90 of: Clarke, P., Egyptian coins in the time of Joseph, J. Creation 26(3):85–91, 2012, creation. com/images/pdfs/tj/j26_3/j26_3_85-91.pdf. Also: Mark, J.J., Jobs in ancient Egypt, worldhistory.org/article/1073/jobs-in-ancient-egypt/, 24 May 2017. Return to text.

- A tuber is a much-swollen underground stem or rhizome used by some plants as a means of nutrient storage; e.g. a potato. Return to text.

- Catchpoole, D., The people that forgot time (and much else, too), Creation 30(3):34–37, 2008. Return to text.

- Using data on around 300 hunter-gatherer societies across the world, it was recently estimated that the earth could support in the order of just 10 million people with a hunter-gatherer lifestyle: Burger, J.R. and Fristoe, T.S., Hunter-gatherer populations inform modern ecology, PNAS 115(6):1137–1139, 6 Feb 2018 | doi:10.1073/pnas.1721726115. Return to text.

- Foster, P., Stone Age tribe kills fishermen who strayed on to island, telegraph.co.uk/, 8 Feb 2006; accessed 7 Jan 2021. Return to text.

- As an example of this teaching, see this short article, aimed at children (grades 6–8): Hunter-gatherer culture, nationalgeographic.org; accessed 7 Jan 2021. Return to text.

- Ember, C.R., Hunter-gatherers (foragers), hraf.yale.edu/ehc/summaries/hunter-gatherers, 1 June 2020; accessed 7 Jan 2021. Return to text.

- Christian, D., Brown, C.S., and Benjamin, C., Big History: Between nothing and everything, McGraw Hill Education, New York, p. 93, 2014. Return to text.

- Kulikovsky, A., Bad history, review of Big History: Between nothing and everything, J. Creation 31(1):36–40, 2017. Return to text.

- Pitman, D., Nephesh chayyāh: A matter of life … and non-life, creation.com, 8 Apr 2014. Return to text.

- Price, P., Animal death before the Fall: cruelty to animals is contrary to God’s nature, creation.com, 17 Mar 2020. Return to text.

- Cosner, L., Animal cruelty and vegetarianism (reply to correspondent), creation.com, 25 Sep 2010. Return to text.

- Also called diathermy or thermocautery, where a heated electrode is applied to tissue. Return to text.

- Carol, M., Animals are more afraid of humans than of bears, wolves and dogs, treehugger.com, 11 Oct 2018. Return to text.

- Nuwer, R., The elusive snow leopard, caught in a camera trap, smithsonianmag.com, 28 Jan 2014; accessed 7 Jan 2021. Return to text.

- Quoted from chapter vii of: Flinders, M., A Voyage to Terra Australis, vol. 1, G & W. Nicol, Pall Mall, UK, pp. 152–173, 1814. The book was republished online by Cambridge University Press in 2010 | doi:10.1017/CBO9780511722387. Return to text.

- Such tameness harks back to the situation which prevailed when every kind of animal was confined on the Ark, near the eight human beings—although admittedly, this was a special case. Since God brought all the creatures to the Ark (Genesis 6:20), their quiescent behaviour during the Flood year perhaps owed as much to divine intervention as it did to their lack of fear of people. Return to text.

- Another example is the kangaroos of the Australian Capital Territory (around Canberra). They are protected from hunting, but this means they are becoming bolder towards humans; and consequently are a road traffic hazard. Return to text.

- Defence-attack structures are discussed in chapter 6 of: Batten, D. (Ed.), Catchpoole, D., Sarfati, J., and Wieland, C., The Creation Answers Book, Creation Book Publishers, Powder Spring, GA, pp. 99–107, 2017. Return to text.

- Fight-or-flight response, britannica.com; accessed 15 Jan 2021. Return to text.

- See ‘Timing of the Fall’ in chapter 13 of: Sarfati, J.D., The Genesis Account, pp. 345–346, 2015. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.