Stunning and stealthy

The amazing electric eel

The electric eel (Electrophorus electricus) lurks in the murky waters of the swamps and rivers of northern South America. With its highly sophisticated system of electrolocation, it is a stealthy predator, having the ability to navigate and hunt in conditions of low visibility. Using ‘electroreceptors’ to detect distortions in an electric field generated within its own body, it can locate a potential meal undetected. It then immobilizes its prey using a powerful electric shock, sizeable enough to stun a large mammal such as a horse, or even kill a man.1 Having a long cylindrical body it closely resembles what we commonly understand by eels (order Anguilliformes); however it belongs to a different fish order (Gymnotiformes).

Fish that can detect electric fields are called electroreceptive and those that can generate strong electric fields like these eels are called electrogenic.

How does the electric eel generate such high voltages?

Electric fish are not alone in generating electricity. In fact all living organisms do this to some degree. The muscles in our own bodies, for example, are controlled by the brain using electric signals. Electrons produced by bacteria can be used to generate electricity in a fuel cell.2 Electric eels produce electricity in the same way as muscles, using energy from food to charge cells called electrocytes (see box below). Although each cell carries only a small charge, by stacking up thousands of these in series, like batteries in a torch, as much as 650 volts (V) can be generated. Arranging many stacks in parallel results in a current of around 1 ampere (A), providing a shock of around 650 watts (W; 1 W = 1 V × 1 A).3

How do electric eels not electrocute themselves?

Scientists are not entirely sure of the answer to this question, but there are some interesting observations that may shed light on the matter. Firstly, the electric eel’s vital organs (such as the brain and heart) are located near the head, away from the electricity-producing organs, and are surrounded by fatty tissue which could act as an insulator. The skin also appears to have insulating properties, as eels with damaged skin have been observed to be more vulnerable to their own electric shocks.

Secondly, electric eels produce some of their most powerful shocks when mating—but without harming the mate. However, if these voltage bursts are emitted when not mating, they can kill the other eel.4 This suggests that they have a protection system that can be switched on.

Could the electric eel have evolved?

It is difficult to imagine how this could have happened through small steps, as the Darwinian process requires. Unless the shock generated was significant from the start, rather than stunning the prey it would have just alerted it to the presence of danger. Moreover, in order to evolve the ability to stun, electric eels must have simultaneously evolved a self protection system. Every time a mutation arose which increased the shock voltage, another mutation would have been required to improve the eel’s electrical insulation—and it would seem unlikely that just one mutation would have been sufficient. Moving organs closer to the head, for example, would likely require a number of mutations to arise together.

Although few fish are able to shock their prey, there are many species that use low voltage electric fields for navigation and communication. Electric eels are members of a group of South American fish, known as ‘knifefish’, all of which have the ability to electrolocate.5 African ‘elephantfish’ (family Mormyridae), are also capable of electrolocation and are said to have evolved this ability alongside their South American cousins. In fact, evolutionists have to argue that electric organs in fish evolved independently eight times.6 Given their complexity, it would seem remarkable, to say the least, that these systems could have evolved once, let alone eight times.

Both the knifefish of South America and the elephantfish of Africa use their electric organs for location and communication, and both use a number of different types of electroreceptors. Both groups also have species producing electric fields with a number of different, complex waveforms.7 Two species of knifefish, Brachyhypopomus bennetti and Brachyhypopomus walteri, are so similar that they might be thought to be the same species, except that the former produces a DC current and the latter an AC current.8,9 The evolution story, however, becomes even more remarkable as we delve deeper. To avoid their electrolocation apparatuses interfering with one another and jamming, some species employ a system whereby each fish changes the frequency of its electric discharge. Significantly, the way this works (the computational algorithm used) is virtually the same in the glass knifefish of South America (Eigenmannia) and the frankfish of Africa (Gymnarchus).10 Could the same jamming avoidance system have evolved independently in two different groups living on separate continents?

A masterpiece of design

The electric eel’s power plant eclipses anything produced by man, being compact, flexible, portable, eco-friendly and self-repairing. All its parts are perfectly integrated into a sleek body which enables the eel to swim with both speed and great agility. From the tiny cells that generate the electricity to the sophisticated software that analyzes distortions in the eel’s self-generated electric fields, it is a tribute to an awesome Creator.

Most of the electric eel is made up of electric organs. The Main organ and Hunter’s organ are responsible for producing and storing the strong electric charge. Sachs’ organ produces the low voltage electric field used for electrolocation.

How do electric eels generate electricity? (semi-technical)

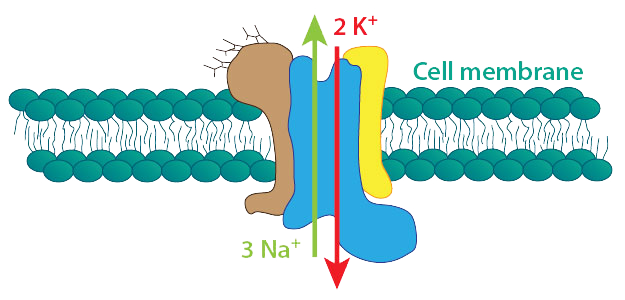

Electric fish generate electricity in a similar way to nerves and muscles in our own bodies. Inside the electrocyte cells, special enzyme proteins called Na-K ATPase pump sodium ions out through the cell membrane and potassium ions in. (‘Na’ is the chemical symbol for sodium and ‘K’ the chemical symbol for potassium. ‘ATP’ stands for Adenosine triphosphate, the energy molecule11 used to drive the pump.) The imbalance of potassium ions inside and outside gives rise to a chemical gradient which acts so as to drive potassium ions back out of the cell. Similarly the imbalance of sodium ions gives rise to a chemical gradient which acts so as to drive sodium ions back into the cell. Other proteins embedded in the membrane act as potassium ion channels, pores which allow the potassium ions to leave the cell. As the positively charged potassium ions accumulate outside the cell, an electrical gradient arises across the cell membrane, with the outside of the cell more positively charged than the inside. The Na-K ATPase pumps are designed so that they select only positive ions as, otherwise, negative ions would also flow and neutralize the charge.

The chemical gradient acts so as to push potassium ions out and the electrical gradient acts to pull them back in. At the point of equilibrium, where the chemical and electrical forces cancel one another out, the outside of the cell will be around 70 millivolts more positive than the inside. Hence, relatively speaking, the inside of the cell is negatively charged to −70 millivolts.

Two potassium ions (K+) enter the cell and three sodium ions (Na+) exit every cycle. The process is driven by energy from ATP molecules.

Yet more proteins embedded in the cell membrane provide sodium ion channels, pores which allow sodium ions to re-enter the cell. Normally these are closed but, when the electric organs are activated, they are opened and the positively charged sodium ions re-enter the cell, driven by the chemical gradient. In this case, equilibrium is reached at the point where the inside of the cell is positively charged to around 60 millivolts. The total voltage change is −70 to +60 millivolts, which is 130 mV or 0.13 V. This discharge occurs very rapidly, in around 1 millisecond. Since around 5,000 electrocytes are stacked up in series, by discharging all the cells simultaneously, around 5,000 × 0.13 V = 650 volts can be generated.

Glossary

Ion

An atom or molecule which carries an electric charge because it has an unequal number of electrons and protons. This will be negative if it has more electrons than protons, and positive if more protons than electrons. Both potassium (K+) and sodium (Na+) ions are positively charged.

Gradient

A change in the magnitude of something when moving from one point to another. For example, as you move away from an open fire, the temperature gets cooler. So the fire is generating a temperature gradient decreasing with distance.

Electrical gradient

A gradient involving the magnitude of electrical charge. E.g., if there are a greater number of positively charged ions outside a cell than inside, there will be an electrical gradient across the cell membrane. Due to like charges repelling one another, there will be a tendency for the ions to move so as to equalize the charge inside and outside. Ion movements due to an electrical gradient occur passively, driven by electrical potential energy, rather than actively, driven by energy derived from an external source such as an ATP molecule.

Chemical gradient

A gradient involving chemical concentration. E.g., if there are a greater number of sodium ions outside the cell than inside, there will be a sodium ion chemical gradient across the cell membrane. Due to the random movements of ions and constant collisions between them, there will be a tendency for the sodium ions to move from a high concentration to low concentration until equilibrium is reached, i.e. until there are the same number of sodium ions either side of the membrane.12 Again, this occurs passively, by diffusion. The movements are driven by the kinetic energy of the ions, rather than from energy derived from an external source such as an ATP molecule.

References and notes

- Piper, R., Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals, pp. 40–42, Greenwood Press, USA, 2007. Return to text.

- Fuel cell that uses bacteria to generate electricity, Science News, 7 January 2008; sciencedaily.com. Return to text.

- Power [watts] = potential difference [volts] × current [amps]. Return to text.

- Electric Eel, Cleveland Metroparks Resource Library; resourcelibrary.clemetzoo.com/animals/164. Last accessed July 2013. Return to text.

- See e.g. our article on the black ghost knifefish, Creation 15(4):10–11, 1993; creation.com/knifefish. Return to text.

- Alves-Gomes, J.A., The evolution of electroreception and bioelectrogenesis in teleost fish: a phylogenetic perspective, Journal of Fish Biology 58(6):1489–1511, June 2001. Return to text.

- Hopkins, C.D., Convergent designs for electrogenesis and electroreception, Current Opinion in Neurobiology 5:769–777, 1995. Return to text.

- Sullivan, J.P. et al., Two new species and a new subgenus of toothed Brachyhypopomus electric knifefishes (Gymnotiformes, Hypopomidae) from the central Amazon and considerations pertaining to the evolution of a monophasic electric organ discharge, Zookeys 327:1-34, 2013. Return to text.

- Science News, AC or DC? Two newly described electric fish from the Amazon are wired differently, 28 August 2013; sciencedaily.com. Return to text.

- Hopkins, ref. 7, p. 775. Return to text.

- Thomas, B., ATP synthase: majestic molecular machine made by a mastermind, Creation 31(4):21–23, October 2009; creation.com/atp-synthase. Return to text.

- See Wieland, C., World Winding Down: A layman’s guide to the Second Law of Thermodynamics, Creation Book Publishers, Powder Springs, GA, 2013. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.