Man the reader

Viewed from a distance, the theory of evolution seems tenable to many people. The beautiful charts showing man’s development from ape-like creatures to Homo sapiens, the anthropological reconstructions of fossil men, artists’ conceptions of transitional forms, and the confident assertions of the ‘fact’ of evolution in textbooks make it seem evolution is a foregone conclusion.

Yet like some smiling Cheshire cat, the ‘body’ of facts to support the theory of evolution is simply not there. It smiles at us, and beckons us to accept that it has flesh and bones, yet when we examine it close up, there is no substance. This is certainly true in the area of man’s ability to read. Rather than supporting the theory of evolution, man’s reading ability points to the wisdom of an Intelligent Designer.

Reading is a process long taken for granted—simply because it usually works so well. Albert Einstein said it is “the most complex task that man has ever devised for himself”.1 E.B. Huey, who spent many years researching reading, put it this way:

“To completely analyze what we do when we read would describe very many of the most intricate workings of the human mind, as well as to unravel the tangled story of the most remarkable specific performance that civilization has learned in all its history.”2

What amazed these two scientists was not so much the fact that man can read, but that he ever developed this ability in the first place. Working from evolutionary presuppositions, it is virtually impossible to unravel the story of the development of reading. Like the Russian cosmonaut who stepped out of his capsule and could not find God, evolutionists are looking in the wrong place. Indeed, one searches evolutionary textbooks in vain for a cogent explanation of the origin of reading.

Why is the origin of reading so difficult to explain from an evolutionary viewpoint? Simply because one must account for the development and existence of several of man’s unique abilities, which must all work together at the same time. If any of these abilities is missing, it is difficult, if not impossible, to read. By examining these abilities in detail, we can gain a greater appreciation of what is involved in reading, as well as how it points to creative design rather than chance plus time.

Reading: unique ability

First, reading presupposes a mind that can symbolize, abstract, and generalize.3 The work of men such as Konrad Lorenz and B.F. Skinner has seemingly shown many similarities between the minds of men and animals. In fact, their work points to the vast gulf that separates man from animal. “There must be something unique about man,” wrote Jacob Bronowski, “or the ducks would be lecturing about Konrad Lorenz, and the rats would be writing papers about B.F. Skinner.”4

The Psalmist described man’s place in the universe best when he wrote:

“What is man, that thou art mindful of him? and the son of man, that thou visitest him? For thou hast made him a little lower than the angels, and hast crowned him with glory and honour.” (Ps. 8:4–5)

The only creature made in God’s image, man is also the only being that thinks about thinking.5 Indeed, thousands of volumes have been written on this subject alone, as the philosophy section of any well-stocked library reveals. Man can both ‘think on his way’ (Ps. 119:59) and respond intellectually and spiritually to a God who “declareth unto man what is his thought.” (Amos 4:13) “Man is but a reed,” the French mathematician Pascal wrote in his Pensees, “but he is a thinking reed.” Man is so made that symbols on the printed page can mean something in his mind.

Spoken language

Second, before reading can take place there must be spoken language. Civilizations have been discovered where there is spoken language, but no writing. But never has a civilization been found where there is writing without spoken language. Reading researchers believe a child must first have a foundation based in spoken language before he can learn to read. This provides him a vocabulary, speech patterns, and the ability to understand the teacher of reading.6

Because language must be learned—and when there is no teacher there is no learning—its origin has baffled evolutionists.7 Anthropologist Alfred Kroeber wrote that the origin of language is “one of the darkest areas in the field of human knowledge”.8

Working from false presuppositions, evolutionists have turned up no reasonable explanation for the origin of language. And the mystery becomes even deeper when we consider that as a general rule if a child does not hear human voices by the age of approximately 13 years, he will never learn to speak. How much easier it is to believe that God gave man the capacity to speak. As Arthur Custance pointed out, the Genesis account of Creation implies Adam was taught to speak by God.9 Speech is indeed “a rare gift, belonging only to the human species”.10

Perception

Along with a highly developed mind that can communicate through symbols and speech, the ability to perceive an encoded message must also be present. Usually this perception takes place through the sense of sight.

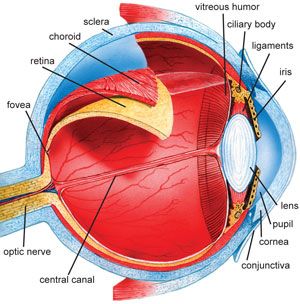

Although sight involves much more than the eyes, a consideration of the eye’s role alone gives us an idea of the complexity of the process.

Long an object of wonder, the eye, on close examination, seemed to William Paley a sure cure for atheism.11 Even Charles Darwin claimed he never contemplated the eye without ‘a cold shudder’.12

The eye’s role in reading is fascinating.

In order for the encoded message to be perceived by the brain, the eyes must first focus with precision on an object so that only one object is seen instead of two.

This is referred to as binocular vision—the ability to form a single image from overlapping fields of vision. The two eyes must also focus simultaneously or the object will be blurred.13

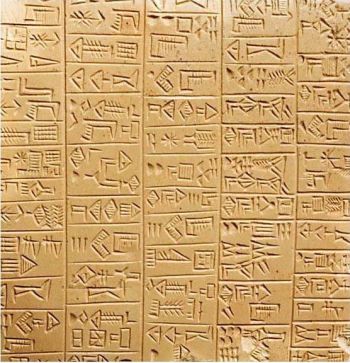

The muscles of the eye must then co-ordinate so the eyes can make short staccato movements and fixations necessary to read sentence after sentence.14 (One wonders why the rest of mankind did not use the reading technique of the Hittites, where the eyes do not return to the left margin but simply follow the sentences as they wind their way down the tablet.)

Concentration

Man also has the psychological ability to sit for hours using his eyes in reading. This is significant because even though primates, cats, and predatory birds have binocular vision, only man has the mental capacity for prolonged concentration.15

Finally, the fact that so many things can go wrong with the eyes is a testimony to their complexity and intricate design.

Yet just as man’s most sophisticated machines are ‘over-designed’ in case something goes wrong (this is especially true with space probes), so God has similarly designed man’s reading equipment: if for some reason these windows of man’s soul are darkened, he can learn to read by his sense of touch through Braille. All of this points to the wisdom of an Intelligent Designer—not the chance happenings of natural selection. Man was truly created as a being who can ‘lift up’ his ‘eyes on high and behold who hath created these things’. (Isa. 40:26)

The ability to think, to speak, and to see—all uniquely human abilities—are all essential for reading. Yet even these abilities are not enough, for the ability to read assumes there is something to read. Thus, there must be the ability to write.

Writing and memory

Evolutionists admit that little is known about the invention of writing.16 The book of beginnings, Genesis, makes little mention of writing per se, though its existence is implied (e.g. ‘the book of Adam’. Gen. 5:1). However, the longevity of men such as Adam (930 years), Seth (912 years), Methuseleh (969 years) and other pre-Flood patriarchs provided early man with ‘walking history books’. Moreover, in the morning of man’s existence, his capacity for memorization may have been used to a much greater extent than it is today.

Although there is a limit to what the memory can carry, more can be carried in the ‘warder of the brain’ than we might think.17 Russell Conwell, the Baptist minister who founded Temple University in Philadelphia, USA, is said to have been able to quote William Blackstone’s four-volume Commentaries on the Laws of England at will, and it has long been a boast of the Jews that if all the Talmud were destroyed, 12 learned rabbis would restore it from memory.18

Man’s ability to write is another of those unique combinations of skills that sets man apart from the rest of creation. Though several animals—Egyptian vultures, chimpanzees, burrowing wasps, sea otters—can use ‘tools’,19 only man can wield the most impressive tool of all: the pen.

In the early 19th century, English theologian William Paley eloquently wrote of man’s ability to write:

“Or let a person only observe his hand whilst he is writing: the number of muscles which are brought to bear upon the pen; how the joint and adjusted operation of several tendons is concerned in every stroke, yet that five hundred strokes are drawn in a minute. Not a letter can be turned without more than one, or two, or three tendinous contractions, definite, as both to the choice of the tendon, and as to the space through which the contraction moves; yet how currently does the work proceed! And, when we look at it, how faithful have the muscles been to their duty—how true to the order which endeavour or habit hath inculcated! For let it be remembered, that, whilst a man’s handwriting is the same, an exactitude of order is preserved, whether he write well or ill.”20

Early books

Man’s powers of concentration in writing have been well demonstrated in history. Medieval scribes, for instance, copied the Scriptures for six hours a day, month after month, often under what we would consider intolerable conditions. Ancient and medieval man depended on this ability, however, since it was the only way books could be produced. One medieval scribe, Cassiodorus of Vivarium, expressed this dependence when he wrote in the 6th century AD:

“By reading the divine Scriptures [the scribe] wholesomely instructs his own mind, and by copying the precepts of the Lord he spreads them far and wide. What happy application, what praiseworthy industry, to preach unto men by means of the hand, to untie the tongue by means of the fingers, to bring quiet salvation to mortals, and to fight the Devil’s insidious wiles with pen and ink! For every word of the Lord written by the scribe is a wound inflicted on Satan. And so, though seated in one spot, the scribe traverses diverse lands through the dissemination of what he has written …

… Man multiplies the heavenly words, and in a certain metaphorical sense, if I may dare so to speak, three fingers are made to express the utterances of the Holy Trinity. O sight glorious to those who contemplate it carefully! The fast-travelling reed-pen writes down the holy words and thus avenges the malice of the Wicked One, who caused a reed to be used to smite the head of the Lord during the Passion.”21

The earth is uniquely fitted for reading and writing. Isaiah said that God ‘created it not in vain, he formed it to be inhabited’ (Isa. 45:18)—to be inhabited by beings who can read and write. Thus, we should expect to find on the earth abundant materials with which, and on which, to write. And this is the case. Pens and ink are found all over the world. Materials to write on can also be found almost anywhere. Such materials include clay tablets, stone, bone, wood, leather, various metals, potsherds, papyrus, parchment, paper,22 silk, and bamboo.23 For the most part, these materials are inexpensive.

It is significant that historically our best writing materials have come from living things, which apparently do not exist anywhere else in the universe. Like the mother’s womb which provides the embryo with everything it needs for survival, so God has made the earth to provide for man’s needs, including his need to communicate through the written word.

The abilities to think, to speak, to see and understand, and to write—all are necessary for reading to take place. The complexity of these abilities points to an Intelligent Designer, the God of the Bible.

As creationist research continues to grow, and more areas are examined in the light of Scripture and true science, the facts support creation, not evolution. Certainly there are cats without grins, just as there are facts without theories to give them meaning. But a grin without a cat? Like evolution, such animals belong only in the wonderland of man’s imagination.

References and notes

- Albert Einstein, quoted in Dechant, E., Reading Improvement in the Secondary School, Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, N.J., p.5, 1973. Return to text.

- E.B. Huey, quoted in Kolers, P.A., Experiments in Reading, Scientific American 227(1):84–91, July 1972. Return to text.

- Kroeber, A.L., Anthropology: Culture Patterns and Processes, Harcourt, Brace, and World, New York, p.7, 1948. Return to text.

- Bronowski, J, The Ascent of Man, Little, Brown and Company, Boston, p. 412, 1973. Return to text.

- Yonge, K.A., Of Birds, Bats, and Bees: A Study of Schizophrenic Thought Disorders, Canadian Psychiatric Association Journal 3(1):1–10, 1958. Return to text.

- Burmeister, L.E., Reading Strategies for Middle and Secondary School Teachers, Second Edition, Addison-Wesley Pub. Co., Reading, Mass., p.23, 1974. Return to text.

- Langer, S., Philosophy in a New Key, Mentor Books, New American Library, New York, pp.87–88, 1952. Return to text.

- Ref. 3., p.32. Return to text.

- Custance, A.C., Genesis and Early Man, The Doorway Papers Vol.II, Zondervan Pub. House, Grand Rapids, pp.250–271, 1975. Return to text.

- Stewart, E.W., Evolving Life Styles, McGraw Hill, Inc., New York, p.392, 1973. Return to text.

- Paley, W., Natural Theology, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp.105–109, 1963. Return to text.

- Leakey, R.E., Introduction to The Illustrated Origin of Species, by Charles Darwin, Faber and Faber Ltd, London, p.16, 1979. (Quoted from Darwin’s confession to American naturalist Asa Gray in 1860.) Return to text.

- Ref. 6., p.23. Return to text.

- Dechant, E., Reading Improvement in the Secondary School, Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, N.J., p.21, 1973. Return to text.

- Oakley, K.P., Skill as a Human Possession, in A History of Technology, Vol.l, ed. Charles Singer et al., Oxford University Press, Oxford, p.12, 1954. Return to text.

- Chard, C.S., Man in Prehistory, Second Edition, McGraw-Hill Book Co., New York, p.260, 1969. Return to text.

- Barber, C.L., The Story of Speech and Language, Thomas Y. Cromwell, Co., New York, p.50, 1964. Return to text.

- Edersheim, A., Sketches of Jewish Social Life, Wm. B. Eerdmans Pub. Co., Grand Rapids, p.129, ff, reprinted 1978. Return to text.

- Custance, A.C., Evolution or Creation? The Doorway Papers, Vol. IV, Zondervan Pub. Co., Grand Rapids, pp.264–265, 1976. Return to text.

- Ref. 11., p. 147. Return to text.

- Cassiodorus: Senatoris Institutiones, edited from the manuscripts by Mynors, R.A.B., Oxford University Press, 1. xxx. 1, 1937. Return to text.

- Metzger, B., The Text of the New Testament, Oxford University Press, New York, pp.17–18, 1964. Return to text.

- Tsien, T-H., Written on Bamboo and Silk, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp.90, 114, 1962. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.