Journal of Creation 24(3):122–127, December 2010

Browse our latest digital issue Subscribe

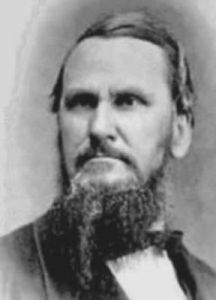

Robert L. Dabney—a rock in the storm of 19th century natural history

Despite widespread compromise with Lyell and Darwin by nineteenth-century theologians, some remained faithful, arguing against the new theories of uniformitarianism and evolution. Robert L. Dabney was as able a Presbyterian theologian as his better known contemporaries at Princeton University, and unlike them, remained staunchly opposed to secular natural history.

Many Christians have chronicled the sad decline of the Church in the face of Lyellian geology and Darwinian biology. Those thinkers who stood fast on Scripture were attacked by both secularists and compromising clerics. Theologians of the time were unable to stem the tide, often succumbing to the siren song of secular natural history or trading their approval for academic respectability. For example, Princeton Seminary, long the bastion of orthodox Presbyterianism, succumbed when their leading scholars, Benjamin B. Warfield (1851–1921) and Archibald A. Hodge (1823–1886), failed to see the worldview behind the “new science”. Compromise led to compromise, and in turn to the decline of Princeton, finally forcing J. Gresham Machen (1881–1937) to break away and form Westminster Seminary. It is a tragic plot that has been replayed more times than I Love Lucy.

But there is always light in darkness, and though Hodge and Warfield remain respected theologians, Robert L. Dabney (1820–1898) was arguably the ablest Presbyterian theologian of the 19th century, despite faulty and inconsistent views on slavery. Dabney (figure 1) graduated from and taught at Union Theological Seminary in Richmond, Virginia. He took leave during the Civil War to become the adjutant for General “Stonewall” Jackson, whose wife was the cousin of Dabney’s wife. Before he died, Jackson called Dabney “the most efficient officer he knew”.1 After the war, Dabney wrote a famous biography of Jackson,2 and his lectures were published by his students as a systematic theology.3 Dabney moved to Austin, Texas in 1883, and founded Austin Theological Seminary, where he remained until his death.

After the war, Dabney feared the spread of liberalism that had captured the northern Presbyterians (United Presbyterian Church in the United States of America). He stood firmly against that trend the rest of his life, credited by Johnson1 with preventing the reunion of the northern and southern Presbyterians as a means to preserve orthodoxy in the southern church (Presbyterian Church in the United States). One of the issues separating Dabney from many of his northern peers was his uncompromising opposition to the rising secularism in science, exhibited in both Darwinian biology and Lyellian geology. He was the leader of the faction in the southern church that kept compromise with either of the ‘new sciences’ at bay until the early 1900s, decades after the northern church had surrendered to secular science and accompanying theological liberalism. His arguments, as presented in the classroom in the 1860s and 70s, and published in his Systematic Theology, are still cogent and worth re-examining. His foresight was incredible, given the novelty of both subjects and that both were outside his discipline.

Dabney on Darwin

Dabney saw Darwinism as a facet of a new worldview, comparable to both Greek Atomism and Epicureanism. He marshalled arguments against Darwin, many of which are still relevant. This section summarizes his views from his Systematic Theology in the order he presented them. He summed up his opinion of Darwin in succinct and blunt terms:

“‘Darwinism’ happens just now to be the current manifestation, which the fashion of the day gives to the permanent anti-theistic tendency in sinful man. As long as men do not like to retain God in their knowledge, the objection to the argument for His existence will re-appear in some form … This recent evolution theory verges every year nearer to the pagan atomic theory.”4

In other words, despite early religious support for Darwin from naïve Christians, Dabney saw evolution’s true philosophical home was materialism.

Necessarily atheistic

Dabney saw the links between evolution and materialism. It was a crucial point for him; he started his chapter by noting that the materialist argument of an infinite regress fails at the point of cause and effect, and that evolution can be seen as an attempt to overcome that problem by showing that “the series contains within itself a power of differentiating its effects, at least slightly”.5 He goes on to assert:

“The tendency of this scheme is atheistic. Some of its advocates may disclaim the consequence, and declare their recognition of a God and Creator, we hope, sincerely. But the undoubted tendency of the speculation will be to lead its candid adherents where Dr. Leopold Büchner has placed himself, to blank materialism and atheism.”6

Subsequent decades have vindicated that insight. Dabney also recognized that atheism would inevitably have a social dimension by affecting mankind’s self-image:

“In assigning man a brute origin, it encourages common men to regard themselves as still brutes. Have brutes any religion?”6

At root, evolution removes the distinction between spirit and matter, removing the possibility of the human soul, as we saw decades later in the works of men like Julian Huxley and Bertrand Russell.

DARWIN | DABNEY |

|---|---|

| Natural selection adequate to explain diversity of life, past and present. | Removing God as cause of life leaves material cause, therefore system will move to atheism. |

| Natural selection is a random material process. | ‘Selection’ implies choice which implies mind. Misleading metaphor. |

| Progression of fossils through time demonstrates evolution. | Evolution should produce myriads of transitional forms; none yet found. |

| Selective breeding is a modern analogy of natural selection. | Not natural, human directed. Also we observe tendency towards uniformity in natural settings, i.e. dogs to mutts. |

| Man evolved from lower forms in an unbroken chain of evolution. | Man’s mind and soul are distinct from all animals, therefore they did not evolve. |

| Evolution explains observations of nature. | Weak theory. Unverifiable. No amount of circumstantial evidence can overturn testimony of Scripture. |

| No need of divine action; evolution is driven by chance. Proof of purpose in design is invalid. | Teleological argument accepted by past scientists. Evolutionists assume no design; they do not prove it. |

Selection implies a mind

Dabney then attacked the logic of Darwin’s argument from natural selection.

“The favorite law of ‘natural selection’ involves in its very name a sophistical idea. Selection is an attribute of free-agency, and implies intelligent choice. But the ‘Nature’ of the evolutionist is unintelligent. The cause, if it be a cause, supposed by him in his natural selection, acts blindly and by hap-hazard. Now, whenever we apply the idea of selection, or any other which expresses free-agency, to such effects: we know that we are speaking inaccurately and by mere trope [figuratively].”7

Dabney was a keen logician and pierced Darwin’s faulty logic. As he noted, the very term ‘selection’ refers to choices made by intelligent beings. Darwin failed scientifically too; “this is but giving us a metaphor in the place of induction”.7 Darwin’s errors were minimized by secularists for many decades. The failure of secular philosophers at that time to acknowledge them as directly as Dabney does remind us of Paul’s observation that fallen men not only participate in sin but give hearty approval to others that do the same things.

Fossil record does not support theory

Dabney was quick to note problems with Darwin’s argument from the fossil record. Not only were the ‘links’ missing, but there was a much greater problem—the absence of the much greater number of fossil forms expected from the prediction of evolution:

“Then, since the blind cause probably has made ten thousand nugatory experiments for every one that was an advance, the fossil remains of all the experiments, of the myriads of genera of failures, as well as the few genera that were successes, should be found in more immense bulk.”8

In his debate with contemporary paleontologists, who followed Darwin in optimistically assuming that the missing links would turn up, Dabney remained dubious. He has been long vindicated; the fossil record remains ‘incomplete’ and the only ‘evolution’ is that of optimism transforming into pessimism among paleontologists.

Limits to change and Darwin’s invalid use of the argument

Next, Dabney assailed Darwin’s argument from selective breeding, arguing that it was not natural and therefore invalid. In fact, he noted the effects of biological entropy before thermodynamics had been formally defined:

“And when we surrender any individual of the varieties to the dominion of ‘nature,’ the uniform tendency is to degradation.”8

He also noted that greater selectivity in breeding led to a greater tendency of individual breeds to revert back to a natural homogeneity if re-mixed with a general population. Another problem was the inferred limits of selection changes based on observations of diminishing changes as breeding programs progressed, an observation that remains a formidable obstacle to evolutionary biology, and a major reason for the role of mutations in the neo-Darwinian synthesis of the 20th century.

Qualitative distinction between man and animals

Dabney’s ability to see evolution as a wedge for the worldview of Naturalism was demonstrated again by a philosophical argument about the nature of man. Because it was philosophical, not scientific, he clearly recognized that Darwin had moved far outside the bounds of biology. His argument was updated and restated by Adler9 and by creationists.10 In short, Dabney argued for the qualitative distinction between man and all other creatures by virtue of the unique nature of the human mind.

“ … just as he [Darwin] accounts for the evolution of the human hand, from the forepaw of an ape; so all the wonders of consciousness, intellect, taste, conscience, religious belief, are to be explained as the animal outgrowth of gregarious instincts, and habitudes cultivated through them … It ignores the distinction between the instinctive and the rational motive in human actions; thus making free-agency, moral responsibility, and ethical science impossible.”11

Adler9 would later construct a more elegant argument that the presence of conceptual thought, expressed by human language, exhibited a qualitative difference in kind between man and animal, rendering human evolution unlikely.

Evolution is a weak theory

Dabney was a theologian, but was well read in the various disciplines of his time. He understood what made a good scientific theory and what made a bad one. He placed evolution in the latter category:

“The utmost which can possibly be made of the evolution theory, is that it may be a hypothesis possibly true, even after all the arguments of its friends are granted to be valid. In fact, the scheme is far short of this.”11

In other words, evolution was not simply a bad theory because of incomplete evidence; it was a bad theory because it was “unverifiable and incapable of verification”.11 Its weakness as a theory was not simply in the structural and evidential realms. Dabney noted its moral weakness:

“These speculations are mischievous in that they present to minds already degraded, and in love with their own degradation, a pretext for their materialism, godlessness, and sensuality.”12

Unfortunately Dabney underestimated that very degradation, thinking that the theory would never take hold because it was so insulting to man’s moral character. Sadly, we have seen that his view of mankind, even influenced as it was by his Calvinistic view of depravity, still underestimated the depths of depravity in the coming century. Finally, he noted the fatal flaw of the theory. It was based on circumstantial evidence, which is inferior to the historical testimony of the Bible.

“Judicial science, stimulated to accuracy and fidelity by the prime interest of society in the rights and the life of its member, has correctly ascertained the relation between circumstantial proof and competent parole testimony. In order to rebut the word of such a witness, the circumstantial evidence must be an exclusive demonstration: it must not only satisfy the reason that the criminal act might have been committed in the supposed way, by the supposed persons; but that it was impossible, it could have been committed in any other way.”12

Today’s crime drama television emphasizes circumstantial evidence because it makes for a more entertaining format. But the fact remains that direct credible testimony is an attorney’s best friend. Dabney completed the analogy with eyewitness testimony by noting that the Bible came from the most credible possible witness in the universe—God:

“Then even though the evolution hypothesis were scientifically probable, in the light of all known and physical facts and laws, it must yield before this competent witness … As Omnipotence is an agency confessedly competent to any effect whatsoever, if the witness is credible, the debate is ended.”13

It is a sad commentary on the state of the Church that such sound biblical and logical thinking is markedly absent in most contemporary theological understanding of the origins debate.

Design and chance

Darwin brought a screeching end to the European fascination with natural theology that long predated Paley’s famous watch. The debate over purpose in nature is at least as old as Aristotle and was one of Aquinas’ famous proofs of God’s existence—the one Kant admitted to be the most powerful of the theistic proofs.14 Evolutionists have always been quick to use their theory to counter this famous ‘teleological argument’. But it is a futile attempt; the more we learn about nature, the clearer the evidence for purpose and design becomes, as creationists and the Intelligent Design advocates have repeatedly shown.

As Dabney noted, one of the errors in the evolutionary position is the gratuitous assumption of the invalidity of metaphysics—an outgrowth of positivism. Dabney corrected that error by pointing out that metaphysics is distinct from science, but that distinction in no way invalidates metaphysical inquiry. As he noted, both Bacon and Newton were firm proponents of the teleological argument. He swats Spencer’s argument that Paley’s analogy was invalid because it was a mere ‘anthropomorphism’ by noting that Spencer’s point is sophistry because all human knowledge is by definition ‘anthropomorphic’. “To complain of any branch of man’s knowledge on this score is to demand that he shall know nothing!”15

He then delivers the final blow:

“The theists must not assume it [creation in God’s image] at the outset as proved. Very true; and their opponents shall not be allowed to assume the opposite as proved—they shall not ‘beg the question’ any more than we do. But when our inquiries in Natural Theology lead us to the conclusion that in this respect ‘we are God’s offspring’, then He is no longer the ‘Unknown God’.”15

This is a point that modern creationists have begun to make more vocally; that even-handed debate does not mean we begin by accepting the naturalistic presuppositions of our opponents. It is a point that bears frequent repetition.

Sir Charles Lyell (1797–1875)

Sir Charles Lyell (1797–1875)

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.