Atheist with a Mission

Critique of The God Delusion by Richard Dawkins

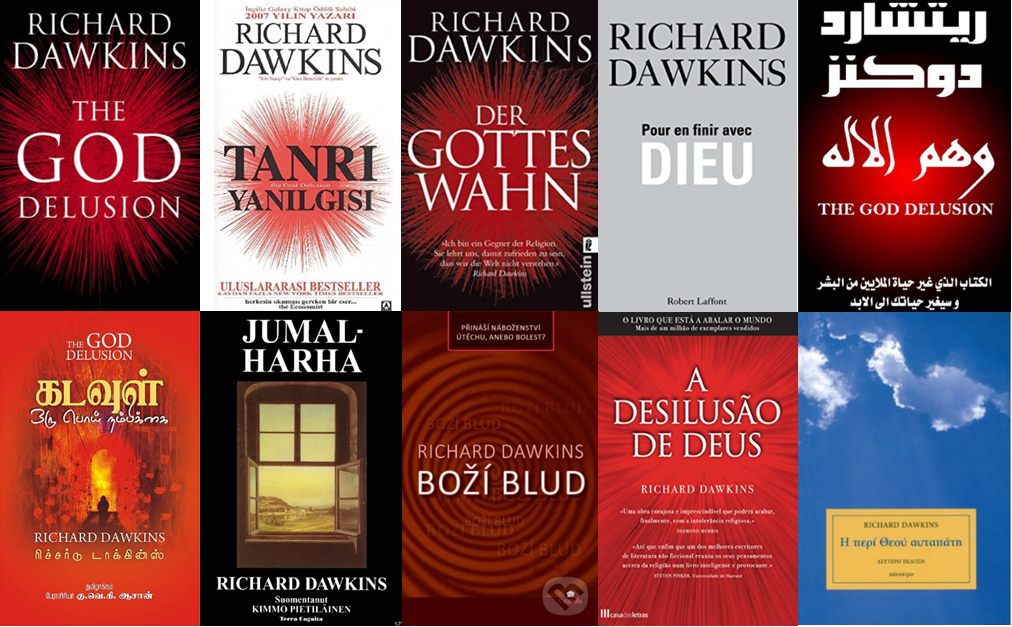

Transworld Publishers, London, 2006

The title of this book immediately betrays the bias of the author—even for those unacquainted with the writings of this former Professor of the Public Understanding of Science of Oxford University, Richard Dawkins. Just to skim the chapter contents is to give one a forewarning of what to expect. For instance, Chapter 1 is entitled ‘A deeply religious believer in no God.’ Chapter 4: ‘Why there almost certainly is no God.’ Chapter 7 is ‘The ‘Good’ Book and the changing moral Zeitgeist’—showing Dawkins’ absolute dislike of the message of the Judeo-Christian Scriptures. More provocatively still, the ninth chapter is ‘Childhood, abuse and the escape from religion.’ The single appendix is ‘a partial list of friendly addresses, for individuals needing support in escaping from religion.’

So much for any attempt at balance and objectivity—this book is certainly not a disinterested search for truth and is devoid of any careful weighing of evidence, for and against his thesis. Rather, it is this author’s most polemical work, that of a man driven by an unholy zeal to depose the God he claims to disbelieve in but transparently hates.

‘I am attacking God, all gods, anything and everything supernatural, wherever and whenever they have been or will be invented.’ (p. 36: emphasis added in all quotes unless otherwise stated)

However, he takes pains to inform his reader that his venom is mostly reserved for monotheistic forms of God and one in particular:

‘Unless otherwise stated, I shall have Christianity mostly in mind, but only because it is the version with which I happen to be most familiar. … I shall not be concerned at all with other religions such as Buddhism or Confucianism.’ (p. 37)

Dawkins gets angry with what he views as the unhealthy and undeserved respect accorded to religious belief and closes the first chapter with:

‘… my own disclaimer for this book. I shall not go out of my way to offend, but nor shall I don kid gloves to handle religion any more gently than I would handle anything else.’ (p. 27)

Ironically, the first sentence of chapter two is a veritable torrent of abuse1 directed at ‘The God of the Old Testament … arguably the most unpleasant character in all fiction …’ Christians would find it deeply offensive and blasphemous. Similar outbursts appear elsewhere but when a professed atheist engages in such frequent name-calling—‘psychotic delinquent’ (p. 38), ‘monster’ (p. 46) and ‘evil monster’ (p. 248) will suffice as examples—one wonders how secure he really is in his atheism.

Such animosity is unlikely to inspire confidence in the reader who wishes to be presented with a well-argued cogent case but will obviously bring plaudits from Dawkins’ most ardent supporters (e.g. Playwright just plain wrong). The perceptive reader—regardless of their bias—will not fail to notice the contradiction between this antagonism towards the Judeo-Christian God, illustrated by numerous outbursts against His attributes, and the following claim:

‘I am not attacking the particular qualities of Yahweh, or Jesus, or Allah …’ (p. 31)

However, it is not for nothing that Dawkins has been described as ‘Darwin’s Rottweiler’;2 his claimed rationale is spelt out as follows:

‘Instead I shall define the God Hypothesis more defensibly: there exists a superhuman, supernatural intelligence who deliberately designed and created the universe and everything in it, including us. This book will advocate the alternate view: any creative intelligence, of sufficient complexity to design anything, comes into existence only as the end product of an extended process of gradual evolution.’ (emphases in original; p. 31)

Those who have seen Dawkins’ television documentaries ‘Root of all evil?’3 will be familiar with the tenor of his rhetoric on what he here calls the God Hypothesis. Like those programs, The God Delusion spews forth more of the same unsubstantiated claims and specious arguments. Of course, those who are desperate for justification of a world-view that removes accountability to the Creator and Judge of all human beings will be blind to these fatal flaws. Consequently, Matt Ridley—author of books on genetics and human behaviour—endorses this polemic as,

‘… so refreshing … It feels like coming up for air.’

More disturbingly still, Philip Pullman—acclaimed author of the award-winning children’s trilogy, His Dark Materials—says,

‘It is so well written, in fact, that children deserve to read it as well as adults. It should have a place in every school library—especially in the library of every ‘faith’ school.’

Unfortunately, Dawkins has since published an illustrated book aimed at influencing children towards a godless worldview, The Magic of Reality (2011). Why read and review a 400-page treatise of a man’s hatred of God? Simply because, in spite of Richard Dawkins’ occasional rants, he is so widely promoted in the mainstream media that he cannot be ignored. While it is true that a number of non-believers do smell a rat when they observe such blatant antireligious bias, many more—including a constituency of his readers that attend churches—accord this man’s writings and opinions with considerable honour. The limitations of a review mean there is much that begs for comment or critique that must be ignored, while seeking to arm the reader with many usable Dawkins quotations.

Who is deluded?

Early on, Dawkins emphasises that The God Delusion does not refer to the physicists’ God (see Einstein, the universe and God) but to supernatural gods, especially Yahweh of the Old Testament (p. 20). It is believers in this God who are the really deluded ones and this is why he has written what he unashamedly describes as ‘a book on religion’ (p. 351); albeit advocating a view that is indistinguishable from humanism, rather than (as he asserts) no religion at all:

‘The truly adult view, by contrast, is that our life is as meaningful, as full and as wonderful as we choose to make it. And we can make it very wonderful indeed.’ (p. 360)

‘The atheist view is correspondingly life-affirming and life-enhancing, while at the same time never being tainted with self-delusion, wishful thinking, or the whingeing self-pity of those who feel that life owes them something.’ (p. 361)

Those who happen to reject Dawkins’ self-described ‘atheistic world-view’ (p. 344)—or yet worse, creationists—are singled out for the professor’s most scathing ridicule: ‘unsophisticated Christians’ (p. 94) and ‘dyed-in-the-wool faith-heads’ (p. 5). ‘Creationist “logic” is always the same’ (p. 121) and even intelligent design theorists are ‘lazy and defeatist’ (p. 128) according to this Oxford sage. Those who believe in irreducible complexity are ‘no better than fools’ (p. 129). In fact, Dawkins makes no effort to moderate his contempt—after all he is an atheist, and atheism is not even ‘tainted with self-delusion’:

‘… atheism nearly always indicates a healthy independence of mind and, indeed, a healthy mind.’ (p. 3)

The man’s arrogance is palpable. At one point, having attacked irreducible complexity, he says:

‘… we on the science side must not be too dogmatically confident.’ (p. 124)

Ignoring for a moment the false science-vs-creation sleight-of-hand, the irony is that Dawkins is utterly dogmatic and insistent that his own views on religion are superior to all others! He seems genuinely unaware of his crass hypocrisy when he writes:

‘Far from respecting the separateness of science’s turf, creationists like nothing better than to trample their dirty hobnails all over it.’ (p. 68)

This is rich, appearing as it does in a book by a scientist that purports to engage with theology. Indeed, philosopher and Marxist Terry Eagleton opened his own review of The God Delusion with these words:

‘Imagine someone holding forth on biology whose only knowledge of the subject is the Book of British Birds, and you have a rough idea of what it feels like to read Richard Dawkins on theology.’4

Similarly, leading philosopher Alvin Plantinga argues5 that Dawkins’ forays into philosophy could be called sophomoric were it not a grave insult to most sophomores.

Who are you calling a fundamentalist?

Those who adhere to a belief in divine revelation subvert science, claims Dawkins.

‘By contrast, what I, as a scientist, believe (for example, evolution) I believe not because of reading a holy book but because I have studied the evidence.’ (p. 282)

‘… and we would abandon [evolution] overnight if new evidence arose to disprove it. No real fundamentalist would ever say anything like that. … But my belief in evolution is not fundamentalism, and it is not faith, because I know what it would take to change my mind, and I would gladly do so if the necessary evidence were forthcoming.’ (p. 283)

Ah, but does he really know his own mind—which after all is ultimately just the by-product of random atomic collisions in his world-view? The professor is on record as saying something very different the previous year:

‘I believe, but I cannot prove, that all life, all intelligence, all creativity and all “design” anywhere in the universe is the direct or indirect product of Darwinian natural selection.’6

Yet elsewhere he derides Christianity for allegedly believing things without proof (ignoring Gödel’s famous incompleteness proof that any system as complex as arithmetic will have true statements that are unprovable within the system), so he shows his hypocrisy. Certainly Christians start from axioms, i.e. starting propositions believed to be true without proof, although it is rational to do so as we have explained—and all belief systems start with axioms, as Dawkins illustrates. And does he seriously expect anyone to believe that he would ‘gladly’ change his mind about evolution if the evidence conclusively falsified it? In a rare instance of (feigned?) even-handedness, Dawkins actually claims,

‘I do not, by nature, thrive on confrontation. I don’t think the adversarial format is well designed to get at the truth …’ (p. 281)

Yet, this entire book furnishes ample evidence that he has failed to follow his own advice!

A sampling of arguments against God

The fact that Dawkins’ critiques of many carefully argued and long-standing arguments for God’s existence are dealt with in very few pages tells us more about the power of his own self-belief than the soundness of his refutations. For instance, arguments that invoke Thomas Aquinas’ ‘Unmoved Mover’ and ‘Uncaused Cause’ (or similar) are plain wrong, he says in a blatant ipse dixit,7 because the implied/explicit infinite regress must also apply to God himself (p. 77–78) (although philosophers argue cogently that only that which has a beginning needs a cause). Chapter 3 barely scratches the scratch on the surface with respect to other philosophical arguments for the Divine. As for ‘the argument from personal experience’ (p. 87–92), Dawkins believes that this kind of thing simply demonstrates ‘the formidable power of the brain’s simulation software’ (p. 90). But then, how can we be sure that his atheistic just-so story-telling doesn’t demonstrate the same thing, according to his own ‘reasoning’?

‘The argument from Scripture’ (its reliability) is dispatched in only five pages and contains some especially fatuous statements, such as:

‘The historical evidence that Jesus claimed any sort of divine status is minimal. … there is no good historical evidence that he ever thought he was divine.’ (p. 92) [but see The Divine Claims of Jesus and Jesus’ Assertion of Godhood: Miscellaneous Claims]

‘Nobody knows who the four evangelists [gospel writers] were, but they almost certainly never met Jesus personally.’ (p. 96) (of course ignoring real historical evidence such as Gospel Dates, Gospel Authors, Gospels Freedoms)

‘It is even possible to mount a serious, though not widely supported, historical case that Jesus never lived at all …’ (p. 97) [it’s possible to mount a ‘serious, though not widely supported … case’ on anything you like, e.g. the non-existence of Dawkins, but no historian takes the non-existence of Jesus seriously—see Shattering the Christ-Myth]

Each of these assertions is made without a shred of supporting evidence and amount to so much bluff and bluster. Since the nineteenth century, ‘scholarly theologians’ (i.e. liberals) have all but proved the unreliability of the Gospels—so he says. His other sources for alleged contradictions or errors in the New Testament are sceptics like himself, such as a writer for the Free Inquiry, and he actually thinks that embittered apostate charlatans like Brian Flemming are credible. Does he seriously believe that Christians have no answer to the charge that, since Matthew 1 and Luke 3 record very different genealogies, this is a ‘glaring contradiction’ (never mind that theologians have long shown from the original Greek grammar that Luke is presenting Mary’s line)? Predictably, he wheels in gnostic writings to further poison these already muddy waters (p. 96).

‘The central argument’—attacking design

Chapter 4 ‘contains the central argument of my book’, says Dawkins, and he gives a useful six-point summary of it (pp. 157–158). To précis this yet further: It is tempting to explain design using the watchmaker analogy but this is false because the Designer then needs an explanation (again misconstruing the designer as having a beginning in the first place, as well as explaining away the fact that God is not composed of different parts). Ergo, natural selection is the only option and we ‘can now safely say’ design is merely an illusion. An ultimate origin (i.e. of the universe itself) awaits a better explanation but the multiverse theory is favoured by Dawkins, even though the alleged other universes are not observable even in principle, so it is hardly a scientific theory. ‘We should not give up hope’ of finding ‘something as powerful as Darwinism is for biology’ to explain cosmology. That is basically all there is to the book’s central argument and anyone conversant with Dawkins’ previous writings (e.g. Climbing Mount Improbable) will find nothing novel here.8

He does engage with Behe’s concept of irreducible complexity9—though very weakly indeed. After quoting from Darwin, he concedes,

‘The creationists are right that, if genuine irreducible complexity could be properly demonstrated, it would wreck Darwin’s theory. … But I can find no such case. … Many candidates for this holy grail of creationism have been proposed. None has stood up to analysis.’ (p. 125)

One wonders how thoroughly Dawkins has explored each case of claimed irreducible complexity. For instance, his attempt at a refutation of the bacterial flagellum motor is straight out of Kenneth Miller’s discredited book Finding Darwin’s God, an argument that is as fallacious as it is audacious.10 Surprisingly he even gets his facts wrong, claiming that:

‘The flagellar motor of bacteria … drives the only known example, outside of human technology, of a freely rotating axle.’ (p. 130)

‘It has been happily described as a tiny outboard motor (although by engineering standards—and unusually for a biological mechanism—it is a spectacularly inefficient one).’ (pp. 130–131)

On the contrary, Dawkins is apparently ignorant of the F1 ATPase motor,11 direct observations of the rotation of which were published in Nature in 1997; that same year, several scientists shared the Nobel Prize for Chemistry for this discovery. Also, the bacterial flagellum motor is 100% efficient at cruising speed.12 Such errors hardly inspire confidence. (In 2012, a spectacular example rotary motion was published, the seven-motors-in-one apparatus of the fast-swimming bacterium MO-1.)

It’s notable that Dawkins says he recommends Miller’s book to Christians—showing clearly how he treats theistic evolutionists as ‘useful idiots’ who undermine their own faith.

In fact, his insinuation of a ‘god of the gaps’ mentality grossly misrepresents the argument for irreducible complexity. Far from being an intellectual cop-out (‘we can’t imagine how this complexity was produced so God must have done it’), design is the only credible scientific explanation for certain data based on what we do know—it is precisely for this reason that non-theists and agnostics have joined the ID movement.

However, no matter how powerfully a case can be made for irreducible complexity, Dawkins will then appeal to his final ‘clincher’ argument:

‘… the designer himself (/herself/itself) immediately raises the bigger problem of his own origin. … Far from terminating the vicious regress, God aggravates it with a vengeance.’ (p. 120)

Aside from the fallacy pointed out already, Christian philosopher Alvin Plantinga has pointed out that his argument also begs the question by presupposing materialism. In other words, it presupposes that God is composed of the same sort of matter/energy as the universe, and subject to the same laws. Such an approach a priori rules out the notion that God is spirit, is the uncaused First Cause, is eternal, etc. It thus seeks to discredit God’s own claims about Himself without engaging them on their own terms, ruling them inadmissible by default.

Origin of morality

In chapter seven, the missionary zeal of this apostle of atheism becomes very apparent indeed. His thesis is that morality needs neither God nor religion and that the Bible’s standards of morality are abhorrent. First of all, he launches a diatribe against the Old Testament and key players in its history (p. 237–250). To Dawkins, much of the Bible is ‘weird’ and strange so perhaps his theological illiteracy is partly accounted for. Yet, for a man who has clearly studied the Bible—after a fashion—his (mis)use of it in these pages smacks more of calculated deceit.

Almost gleefully, he describes immoral actions (such as Lot’s incest with his daughters in Genesis 19 and the Levite’s behaviour concerning his concubine in Judges 19) and concludes that this shows the Bible is not our source for morality (ignoring that not everything reported in the Bible is endorsed by the Bible—see Is the Bible ‘evil’? Moral accusations against God and Scripture fall flat).

But he also wilfully twists the actions of the heroes of faith—so Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice Isaac is ripped out of all context to make him a child abuser! Moses and Joshua also receive a bashing by this self-appointed theological expert, but his animosity is always at its fiercest when he is persecuting the God that these biblical figures worshipped and served:

‘What makes my jaw drop is that people today should base their lives on such an appalling role model as Yahweh …’ (p. 248).

Dawkins truly lives up to the name ‘A Devil’s Chaplain’13 when he writes about the New Testament, quickly showing his true colours. For instance,

‘… there are other teachings in the New Testament that no good person should support. I refer especially to the central doctrine of Christianity: that of ‘atonement’ for ‘original sin’. This teaching, which lies at the heart of New Testament theology, is almost as morally obnoxious as the story of Abraham setting out to barbecue Isaac, which it resembles—and that is no accident …’ (p. 251)

As an aside, Dawkins never tells us how he defines a ‘good person’. Indeed, he bandies about such terms as ‘good’ and ‘evil’ (often when indulging in ad hominem remarks about his detractors) quite brazenly and fails to justify his inconsistent absolutist position. So,

‘… Hitler and Stalin were, by any standards, spectacularly evil men.’ (p. 272)

‘Faith is an evil precisely because it requires no justification and brooks no argument.’ (p. 308)

By what standards (omitting the Bible which he rejects) does Dawkins make these points? He doesn’t say. And it seems incongruous with his support for eugenics, on the grounds that 60 years is enough time to reconsider some of Hitler’s ideas.

However, what is more pertinent here is that Dawkins reveals his understanding of the central tenets of the Christian faith. Without Adam’s sin, Jesus’ atoning sacrifice for sins (foreshadowed by the Abraham/Isaac incident; i.e. ‘no accident’) becomes meaningless. The doctrine of original sin and the atonement is, as he says, at the very ‘heart of New Testament theology’; we heartily agree. Yet this Gospel is an offence to Dawkins who has chosen to deny God and deny his own sin in order to avoid accountability to his Creator:

‘Original sin itself comes straight from the Old Testament myth of Adam and Eve. Their sin—eating the fruit of a forbidden tree—seems mild enough to merit a mere reprimand. But … They and all their descendants were banished forever from the Garden of Eden, deprived of the gift of eternal life …’ (p. 251)

How tragically ironic that the very doctrines which Dawkins attacks with a vengeance are also denied by theological liberals and by increasing numbers of professing evangelicals—some have lately been downplaying or attacking not only Creation and the Fall of man but also the penal substitution of Christ for sinners.14

‘But now, the sado-masochism. God incarnated himself as a man, Jesus, in order that he should be tortured and executed in atonement for the hereditary sin of Adam. Ever since Paul expounded this repellent doctrine, Jesus has been worshipped as the redeemer of all our sins.’ (p. 252)

Later, Dawkins asks why God couldn’t just forgive sins without sacrifice but he knows the biblical answer and actually refers directly to Hebrews 9:22. So Dawkins does understand Christianity—much better than many ordinary Christians do—but he wilfully rejects it. In fact, he admits to hoping to make atheists out of some of his religious readers (p. 5).

This is an important take-home message. Dawkins is on a mission to undermine faith in the Lord Jesus Christ as the only Saviour of human beings. The pronouncements of theistic evolutionists and others who downplay Genesis as history aid and abet him and his ilk:

‘To cap it all, Adam, the supposed perpetrator of the original sin, never existed in the first place: an awkward fact …’ (p. 253)

Defending the historicity of Adam is something that Dawkins would fully expect creationists to do—though he despises them for doing so. On the other hand, his disdain for fence-sitters (p. 46) and theological compromisers is hard to miss; for example:

‘Oh, but of course, the story of Adam and Eve was only ever symbolic, wasn’t it? Symbolic? So, in order to impress himself, Jesus had himself tortured and executed, in vicarious punishment for a symbolic sin committed by a non-existent individual? As I said, barking mad, as well as viciously unpleasant.’ (emphasis in original; p. 253)

Clearly, Dawkins hates these doctrines for the moral problem that they expose in himself and others but he has another reason too—an originally perfect Creation and Redemption through the atoning work of Jesus are diametrically opposed to his naturalistic world-view, a vision that he believes, passionately, requires no God:

‘I am continually astonished by those theists who, far from having their consciousness raised in the way that I propose, seem to rejoice in natural selection as “God’s way of achieving his creation.”’ (p. 118).

Other examples of Dawkins’ criticism of compromising ‘believers’, who pick and choose which parts of the Bible they are comfortable with, are found on pages 157 (belief in the Virgin Birth and the Resurrection), 238 (Genesis not literal), and 247 (Scriptures symbolic or literal).

Dawkins—man of faith

We have already seen that the author is careful to disparage anything and anyone religious. Chapter 5 is a vain and facile attempt to explain religion’s roots from a naturalistic perspective. Religion might be ‘a placebo that prolongs life by reducing stress’ (p. 167) or perhaps it exists merely as a by-product of some separate entity that gave survival value (not having any survival value of its own; p. 172). For example, it’s good for a child to trust his/her parents (it enhances survival value) but religious beliefs are also, thereby, passed on. Alternatively,

‘Could irrational religion be a by-product of the irrationality mechanisms that were originally built into the brain by selection for falling in love?’ (p. 185)

Having just decried the idea that faith is a virtue (and scorned those who believe in the Trinity but concede their limited comprehension of all it entails), Dawkins gives us his best shot at explaining why religion exists:

‘… memetic natural selection of some kind seems to me to offer a plausible account of the detailed evolution of particular religions.’ (p. 201)

Yet, the ‘meme’ hypothesis of Dawkins merely describes the transmission of ideas and beliefs over generations and falls far short of explaining the origin of religion—amounting to so much hand waving (even according to many evolutionists) and, well, faith (of the blind sort, not the biblical kind). It also ignores the historical evidence for the claims of Christianity, in particular Jesus’ resurrection.

Dawkins believes that morality probably predated religion (p. 207), confident that he, as an atheist, has a firm grasp on the difference between true and false religion. Thus, we are told that the atrocities perpetrated by Hitler (a fanatical evolutionist, incidentally) were carried out by soldiers ‘most of whom were surely Christian’ (p. 276, although atheist and famous evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr testified that biblical Christianity was almost non-existent in Germany when he grew up)! Furthermore, ‘without religion there would be no labels by which to decide whom to oppress and whom to avenge’ in Northern Ireland and ‘the divide [between Protestant and Catholic] simply would not be there’ (p. 259)! Perhaps he has forgotten the Hutu/Tutsi divide in Rwanda. After all, religion is ‘the root of all evil’.3 In contrast, he seeks to reassure the reader:

‘Stalin was an atheist and Hitler probably wasn’t; but … the bottom line of the Stalin/Hitler debating point is very simple. Individual atheists may do evil things but they don’t do evil things in the name of atheism.’ (p. 278)

One hopes that many of his readers are rather more well-informed than Dawkins gives them credit for.15 Christian persecutions were inconsistent with the teachings of Christ, while atheistic persecutions were consistent with atheism—indeed, communists have persecuted non-atheists precisely because they were non-atheists .

So, ‘why are we good’ (chapter 6) if a bloody evolutionary struggle is responsible for human existence?

‘Could it be that our Good Samaritan urges [our altruistic tendencies] are misfirings, analogous to the misfiring of a reed warbler’s parental instincts when it works itself to the bone for a young cuckoo?’ (p. 220–221)

Dawkins is not joking—for humans also, feelings of pity are no different from lust:

‘Both are misfirings, Darwinian mistakes: blessed, precious mistakes.’ (p. 221)

Dawkins is truly a man of considerable faith, witness the following pseudoscientific beliefs that he holds:

- There are probably ‘superhuman’ alien civilizations elsewhere in the universe (p. 72).

- ‘I think it is definitely worth spending money on trying to duplicate [the origin of life] event in the lab and - by the same token, on SETI, because I think that it is likely that there is intelligent life elsewhere’ (p. 138).

- There may well be a plethora of universes (the ‘multiverse’) and he even claims: ‘we are still not postulating anything highly improbable’ (p. 147)!

In addition, he indulges in blatant circular reasoning on several occasions:

‘We exist here on Earth. Therefore Earth must be the kind of planet that is capable of generating and supporting us …’ (p. 135)

‘Darwinian evolution proceeds merrily once life has originated. But how does life get started? The origin of life was the chemical event, or series of events, whereby the vital conditions for natural selection first came about. … The origin of life is a flourishing, if speculative, subject for research. The expertise required for it is chemistry and it is not mine.’ (p. 137)

He is right about his ignorance of chemistry. But, neither does the professor have expertise in theology or astrophysics, yet he discusses these at length. The real reason for his disclaimer is that nobody has the faintest idea how life got started—but that it happened is axiomatic for Dawkins:

‘… we can make the point that, however improbable the [naturalistic] origin of life might be, we know it happened on Earth because we are here.’ (p. 137)

That has to be the ultimate in circularity although there are other instances in the book (e.g. regarding human embryos, p. 300). One of his main arguments against God’s existence, as we have seen, is that such a being demands an explanation but is held to exist by faith. He is seemingly blind to the many incredible things (also complex and demanding an explanation) which he believes as a matter of faith; such as other universes, the spontaneous origin of life and ETs—all without a shred of supporting evidence. Dawkins believes that Darwinism explains the whole shebang:

‘Think about it. On one planet, and possibly only one planet in the entire universe, molecules that would normally make nothing more complicated than a chunk of rock, gather themselves together into chunks of rock-sized matter of such staggering complexity that they are capable of running, jumping, swimming, flying, seeing, hearing, capturing and eating other such animated chunks of complexity; capable in some cases of thinking and feeling, and falling in love with yet other chunks of complex matter. We now understand essentially how the trick is done, but only since 1859.’ (p. 366–367)

And this is the man who is trying to convince his readership that believers in God are deluded!

Abusing education

In view of the foregoing, it is not easy to stomach Richard Dawkins’ sanctimonious attitude towards his dissenters who choose to teach their children a biblical world-view—one which incorporates honour and respect for God and for one’s fellow human beings. He is, by now, infamous for his attacks on Christian schools which dare to expose children to alternatives to his bleak, atheistic take on life—such parents and teachers are guilty of ‘child abuse’ in his celebrated opinion. More than once, Dawkins argues that there is no such thing as a Christian child or a Muslim child (e.g. p. 338 & 339), something that many children would have something to say about! He has a real fixation about this:

‘Fundamentalist religion is hell-bent on ruining the scientific education of countless thousands of innocent, well-meaning, eager young minds. Non-fundamentalist, ‘sensible’ religion may not be doing that. But it is making the world safe for fundamentalism by teaching children, from their earliest years, that unquestioning faith is a virtue.’ (p. 286)

Absolutism, he argues, has a dark side—many times in the book, he equates believers in a literal Genesis or the conservative Christians of the USA with the ‘Taliban’ (e.g. p. 289). Needless to say, he admits little of the dark side of atheistic and evolutionistic intolerance and absolutism and its consequences for the lives of millions during the last century.16 Dawkins may well have modified his opinion somewhat, since writing this, for in 2010 he admitted that true Christians are not committing acts of terrorism and that “Christianity is a bulwark against something worse”.

He expects young people to be exposed to his wisdom, yet how many parents would be happy for their children to imbibe Dawkins’ twisted take on human life:

‘When I am dying, I should like my life to be taken out under general anaesthetic, exactly as if it were a diseased appendix. But I shall not be allowed that privilege, because I have the ill-luck to be born a member of Homo sapiens rather than, for example, Canis familiaris or Felis catus.’ (p. 357)

Dawkins does concede that if, ‘having been fairly and properly exposed to all the scientific evidence, they [children] grow up and decide that the Bible is literally true or that the movements of the planets rule their lives, that is their privilege.’ (p. 327)

But, he says, parents should not impose their views on their children. Of course, the learned professor is exempt from his own advice—witness the incident he related in Climbing Mount Improbable, where he took pains to put his young daughter ‘right’ for taking a teleological view of wild flowers.17 Exposing young people to ‘all the scientific evidence’ clearly would not equate to teaching evolution ‘warts and all’—including its scientific flaws—in Dawkins’ mind!

Finding common ground

Are there any parts of this anti-God disputation with which a creationist might agree? Well, yes, but many are a sad reflection on the state of the church—and of society in general—in our western culture:

‘In England … religion under the aegis of the established church has become little more than a pleasant social pastime, scarcely recognizable as religious at all.’ (p. 41)

‘There seems to be a steadily shifting standard of what is morally acceptable.’ (p. 268)

However, this changing ‘spirit of the age’ (zeitgeist) is something Dawkins approves of. Those who ‘advance’ with the times therefore approve of abortion. Dawkins correctly notes:

‘[For] the religious foes of abortion … An embryo is a ‘baby’, killing it is murder, and that’s that: end of discussion. Much follows from this absolutist stance. For a start, embryonic stem-cell research must cease.’ (p. 294)

But how many pro-lifers realise the foundational (Genesis) basis for defending the sanctity of human life? An ignorance of what the Bible actually teaches in its opening chapters is lamentable. Elsewhere in his book, Dawkins says:

‘I must admit that even I am a little taken aback at the biblical ignorance commonly displayed by people educated in more recent decades than I was.’ (p. 340–341)

Biblical ignorance is a large part of the reason for the moral laxity and relative moral stance taken by so many today (including within churches)—although Dawkins’s point is simply that the Authorized, King James Version of the Bible has important literary merit.

And finally, we would, with Dawkins, highlight this statement (though not in the way he means it):

‘Who, before Darwin, could have guessed that something so apparently designed as a dragonfly’s wing or an eagle’s eye was really the end product of a long sequence of non-random but purely natural causes?’ (p. 116; emphasis in original)

- [Update: see criticisms of this review plus our responses in Dawkins’ Delusion (continued).]

The big question for atheists

So, having read to the end of this long review of an overly-long book promoting atheism, where do we go from here? Professor of Molecular Biology (Biola University) Douglas Axe made the following perceptive comments in 2021:

‘For just a minute or two, put yourself in the place of someone who is determined to deny God. To make that easier, take yourself back to a moment when you yourself were resolved to assert your sovereignty over your life. In those moments (we all have them), God’s presence seems highly inconvenient, so we push him out of our minds. I’m suggesting that atheists are merely people for whom this momentary lapse becomes a consciously adopted way of life. … Atheism is a commitment, not a deduction” (emphasis added).18

Re-featured on homepage: 24 June 2023

References and notes

- No less than twenty adjectives and nouns are hurled at God until the professor has vented his spleen. Return to text.

- Hall, S.S., Darwin’s Rottweiler, Discover 26(9), September, 2005. The article is subtitled: Sir Richard Dawkins: Evolution’s fiercest champion, far too fierce. Return to text.

- Root of all Evil? Channel 4, United Kingdom, presented by Richard Dawkins and screened in two parts during 2006. Return to text.

- Eagleton,T., Lunging, flailing, mispunching, LondonReview of Books 28(20), 19 October, 2006, last accessed 25 January, 2007. The author is Professor of English Literature at Manchester University, UK. Return to text.

- Plantinga, A., The Dawkins Confusion: Naturalism ad absurdum, Christianity Today (Books and Culture), March/April 2007. Return to text.

- Dawkins, R., quoted in: Roger Highfield, Science’s scourge of believers declares his faith in Darwin, Daily Telegraph, 5 January, 2005, p.10. Return to text.

- Ipse dixit (Latin) = ‘He himself said it’, i.e. an unsupported assertion. Return to text.

- See: Sarfati, J., review of Climbing Mount Improbable, Journal of Creation. 12(1):29–34, 1998. Return to text.

- Behe, M. J., Darwin’s Black Box. The Biochemical Challenge to Evolution, The Free Press, 1996. Return to text.

- Miller points out that there are similar components in e.g. the toxin-injection organelle of the plague germ Yersinia pestis and claims that this refutes the claim for irreducible complexity of the flagellum motor. Not so; around three-quarters of the components in this motor are unique and absent from the plague bacterium’s ‘Type III secretory apparatus’ (TTSS). There is actually good evidence that the organelle in Yersinia resulted from degeneration of a functional flagellum—consistent with the Creation/Fall model and in no way undermining the case for irreducible complexity of the flagellum motor. Indeed, evolutionary experts argue that the TTSS must have come first, so Dawkins and Miller are contradicting the best evolutionary theory as well.Return to text.

- This is a subunit of the larger ATP synthase enzyme which is ubiquitous in all living cells, and vital to generate its ‘energy currency’ ATP. See: Sarfati, J., Design in living organisms (motors), Journal of Creation 12(1):3–5, 1998. Return to text.

- DeVowe, S., The amazing motorized germ, Creation 27(1):24–25, 2004. Return to text.

- The title of his book of selected essays, published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 2003. Return to text.

- For example, see White, A.J.M., The lost message of Jesus is no message at all! 15 November 2004. Return to text.

- For instance, see: Bergman, J., Darwinism and the Nazi race holocaust, Journal of Creation 13(2):101–111, 1999; Bergman, J., The Darwinian foundation of communism, Journal of Creation 15(1):89–95, 2001. Return to text.

- Hall, R., Darwin’s impact—the bloodstained legacy of evolution, Creation 27(2):46–47, 2005. Return to text.

- Dawkins, R., Climbing Mount Improbable, Viking Penguin, London, p. 236, 1996. Return to text.

- Axe, D., in Dembski, W.A., Luskin, C. & Holden, J.M. (eds.), The Comprehensive Guide to Science and Faith, Harvest House Publishers, p. 306, 2021. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.