Journal of Creation 26(3):95–100, December 2012

Browse our latest digital issue Subscribe

Creationism and millennialism among the Church Fathers

Some theistic evolutionists and progressive creationists have used the beliefs of the Church Fathers to challenge modern young-earth creationism. In this paper I intend to examine the beliefs of the leading Church Fathers relating to the Genesis creation account in detail and highlight what they believed and why. From this study it is evident that there was in fact a strong link between acceptance of six-day creation and a 6,000-year millennial scheme in order to try and determine when Christ would return. Although there are some differences with modern creationism, a degree of harmony in approaches to biblical hermeneutics is evident. The Patristic use of the Septuagint, however, meant their timeframe was in error, but later acceptance of the Masoretic Text rekindled millennial thinking.

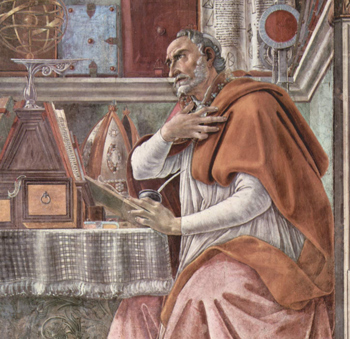

It is, I believe, important to acknowledge that many of the Church Fathers believed that the earth was less than 6,000 years old and that they read the Genesis creation account both literally and symbolically. I will highlight this with reference to works by St Basil (Hexaemeron) and St Augustine (The City of God, De Genesi ad Litteram), as well as consideration of the thoughts of Irenaeus, Justin Martyr, Hippolytus, and Theophilus, among others.1 These Christian leaders lived in the first few centuries AD, and taught in defence of the Christian Church, often against pagan critics. The relevance for us today is that some theistic critics of a young earth claim that this position is a recent development in Christian theology, and that the Church Fathers would have been critical of it as well. Denis Alexander quotes from Augustine to try and make out that the creationist position is in fact an embarrassment to the gospel.2 Roger Forster and Paul Marston also address the beliefs of the Church Fathers, but downplay the significance of their literal reading of Genesis, and emphasize instead the allegorical aspects, and where they do address literal readings it is to gently mock.3 They then seek to break the link between modern young-earth creationism and Christian tradition, and despite the fact that they acknowledge that young-earth creationism was present in the late nineteenth century Victoria Institute, they assert that

“Young-earthism is a clear and radical break [from mainstream Evangelicalism] differing in its whole approach to the issues—and its modern roots are in Seventh Day Adventism not in later nineteenth century Evangelicalism nor in early Fundamentalism.”4

Roger Forster is of course a well-respected Christian leader of the London-based Ichthus Christian Fellowship and linked churches, but this is an unnecessarily strong, and I would argue unsustainable, statement against fellow evangelicals.5 Instead, the truth is more complex than these comments suggests, and as we will see below, the beliefs of the Church Fathers are in tune with modern creationism and evangelical thought, even though differing in some places.

It is clear from a close reading of the Church Fathers that the widely held belief of the church in the first few centuries after Christ was that the creation occurred less than 6,000 years prior to their time of writing; at least it seems to have been the majority opinion among the church leaders. This belief was also seemingly tied in with an understanding of the timing of the Second Coming of Christ and millennial reign; a pressing question for the early church. The millennial scheme symbolically linked six days of creation with 6,000 years of Earth history, with the final millennium rest seen as foreshadowed by the seventh day of rest in the creation account. Looking at the beliefs of some of the Church Fathers in relation to creation, and also in relation to the millennium, what becomes apparent is that a belief in a young Earth was widely held in the early Church by the Church Fathers. This undermines claims that such belief is a recent phenomenon, or is not in tune with traditional Christian theology.

Literal and allegorical readings from Basil and Augustine

Despite the fact that a number of the Church Fathers, such as Origen, emphasized the allegorical over the literal reading of the Genesis creation account, and Forster and Marston highlight the ambiguity in Origen’s thoughts in this matter,6 there was a desire among others to hold in balance both the literal and allegorical readings. Basil, the Cappadocian saint (AD 330–379), acknowledged the ‘laws of allegory’, but also emphasised the literal sense in his Hexaemeron (meaning ‘Six Days’). This was written in elegant prose to be presented as a set of homilies or sermons. It was didactic, that is designed to appeal to the senses and be informative, and in this case expressing both symbolic meaning and literal truth.

“I know the laws of allegory, though less by myself than from the works of others. There are those truly, who do not admit the common sense of the Scriptures, for whom water is not water, but some other nature, who see in a plant, in a fish, what their fancy wishes, who change the nature of reptiles and of wild beasts to suit their allegories, like the interpreters of dreams who explain visions in sleep to [m]ake them serve their own ends. For me grass is grass; plant, fish, wild beast, domestic animal, I take all in the literal sense. ‘For I am not ashamed of the gospel.’”7

In other words, although symbolism was recognized in the biblical narrative, Basil also upheld the literal account as important, including the length of a day. He saw that in Genesis a day was a period of 24 hours.

“‘And there was evening and there was morning: one day.’ And the evening and the morning were one day. Why does Scripture say ‘one day the first day’? Before speaking to us of the second, the third, and the fourth days, would it not have been more natural to call that one the first which began the series? If it therefore says ‘one day’, it is from a wish to determine the measure of day and night, and to combine the time that they contain. Now twenty-four hours fill up the space of one day—we mean of a day and of a night.”8

But Basil also interpreted the phrase ‘one day’ (from the Septuagint (LXX) rendering of Genesis 1:5) as an allegory for eternity, thus ‘one day’ may be considered both a 24-hour period and an expression for the eternal domain of Heaven. Similarly, the seven-day week represents a temporal period covering the creation, but also symbolic of human history with the eighth day compared with the ‘one-day’ and the time when creation will be finally perfected and consummated in eternity.

“God who made the nature of time measured it out and determined it by intervals of days; and, wishing to give it a week as a measure, he ordered the week to revolve from period to period upon itself, to count the movement of time, forming the week of one day revolving seven times upon itself … . If then the beginning of time is called ‘one day’ … it is because Scripture wishes to establish its relationship with eternity. … this day without evening, without succession and without end is not unknown to Scripture, and it is the day that the Psalmist calls the eighth day, because it is outside this time of weeks.”8

Basil here has some understanding of the prophetic significance of the Creation Week in millennial terms from readings of the Old Testament, apparently here referencing the ‘octave’ in Psalm 6:1 and 11:1,9 although there might be an intimation here also that the first day should be seen in a divine, eternal context.

Although engaging reasonably well with the science of his time with its Greek influence, he did not believe Christians should be overawed by it. For instance, when discussing the size and shape of the earth he suggested that different natural philosophers contradict one another and that Moses was silent upon such questions. From the thought of such futility he asks whether we should “prefer foolish wisdom to the oracles of the Holy Spirit”. Furthermore, he maintains that Greek philosophers should not mock Christian beliefs at least until they are settled themselves upon what is true.10

But where he did engage with the science of his time it was in Aristotelian terms, some of which we would reject today as seemingly accepting geocentricism and spontaneous generation, although for Basil such generation was in response to the divine word spoken into the ground at creation11 (spontaneous generation as a result of the divine Word may also be reflected in Augustine’s rationes seminales).12 But on the question of accepting a ‘hard roof’ dome-like firmament over the earth, as Forster and Marston suggest in rather unflattering terms, Basil instead compared analogically the strength of the Firmament to that of the strength of the air when exposed to thunder, and from Isaiah maintained that the heavens “are a subtle substance, without solidity or density”,13 and Basil further asserted that it is not matter as we know it on Earth:

“It is not in reality a firm and solid substance which has weight and resistance … . But, as the substance of superincumbent bodies is light, without consistency, and cannot be grasped by any one of our senses, it is in comparison with these pure and imperceptible substances that the firmament has received its name.”14

There is a sense then that for Basil the literal reading concerning the starry heavens retained a spiritual aspect, a way of viewing creation that is lost with the dominance of materialism in science, and is sometimes overlooked by those of us committed to creation science as well, especially in relation to understanding the pre-Fall world. For Basil the writings of Moses through the inspiration of the Holy Spirit were given to provide spiritual truths, and these are more important than exact measurements and distances that are not of interest to the Genesis account, but he seems to have accepted the times and dates given in a literal and symbolic manner.

Augustine (AD 354–430) similarly interpreted Scripture both literally and symbolically (or allegorically), thus attempting to discern spiritual truths. He recognized an overlap between both types of readings with the symbolic arising from real people and events. Concerning Noah’s Flood, Augustine wrote in a chapter in The City of God that

“… no one ought to suppose either that these things were written for no purpose, or that we should study only the historical truth, apart from any allegorical meanings; or, on the contrary, that they are only allegories, and that there were no such facts at all … .”15

This approach of Augustine followed from the disagreement between the Alexandrian School, particularly of Origen, that emphasized the allegorical above the literal, and on the other side, the Antiochene School that focussed upon reading the prophetic writings historically with less regard for the wider theological significance.16 As such there was reluctance to see Christ in the Old Testament texts within the excessively literalistic framework. Augustine, though, saw symbolism relating to Christ and the Cross in the account of Noah and the Ark. The Augustinian approach then sought to blend together the theological and symbolic aspects, where we can see Christ in the Old Testament as well as the New, and where we see our faith having a real impact upon the material world, including through the study of creation. It is this combined literal–symbolic reading that allowed the early church to infer 6,000 years of earth history from the six days of creation to their time of writing.

The age of the earth and six days of creation

Influence for the symbolic linkage between the six days of creation and the six thousand years until the millennial reign of rest may have been passed down directly from the Apostles, especially John, the author of Revelation. Irenaeus, who lived during the 2nd century ad, claims to have received the teaching from Papias and Polycarp, who received it directly from John.17 Influence may also have derived from Peter’s writing, wherein the Apostle was responding to questions about the return of Christ. Peter wrote that for God “a day is like a thousand years” (2 Peter 3:8) and that the Christians should be patient regarding the question of Christ’s return. However, it is less clear whether Peter was specifically making a millennial link here, or just a general point about God’s timeframe in relation to our own. Bearing in mind Christ’s injunction not to be over-concerned with times and dates (Acts 1:7), Peter might then have been only making a general point. A millennial scheme is also present in the early Epistle of Barnabas (probably written AD 70–100).

“Attend, my children, to the meaning of this expression, ‘He finished in six days.’ This implieth that the Lord will finish all things in six thousand years, for a day is with Him a thousand years. And He Himself testifieth, saying, ‘Behold, to-day will be as a thousand years.’ Therefore, my children, in six days, that is, in six thousand years, all things will be finished. ‘And He rested on the seventh day.’”18

Reference to the notion that a ‘day is as a thousand years’ is also found in the writing of Justin Martyr (AD 100–165), although Justin used it in a slightly different way to others such as Irenaeus and instead links it to passages from Isaiah. In his Dialogue with Trypho a Jew he pointed out that there would be a millennial reign from a renewed Jerusalem and that the lives of the saints would be sustained through the thousand years. He quotes from the prophets Ezekiel and Isaiah, and John in Revelation. He also obscurely linked this to the age of Adam at his death.

“For as Adam was told that in the day he ate of the tree he would die, we know that he did not complete a thousand years. We have perceived, moreover, that the expression, ‘The day of the Lord is as a thousand years’ is connected with this subject.”19

The implication is that the curse of death upon Adam would not be immediate, but within a period of one thousand years; i.e. one ‘day’ because Adam was told he would die in the ‘day’ he ate the fruit. Adam lived 930 years. Some may suggest this supports the day-age scenario, as Forster and Marston do,20 but among the early Christian writers the millennial scheme was more clearly linked to the six days of creation. As noted, the creation and millennial timeframe is clearly set out in the writing of Irenaeus. He held that the earth was literally less than 6,000 years old and that this related symbolically to the return of Christ and the fulfilment of history. Christ would return and then reign for one thousand years, representing the Sabbath day of rest. Irenaeus wrote:

“For in as many days as this world was made, in so many thousand years shall it be concluded. And for this reason the Scripture says: ‘Thus the heaven and the earth were finished, and all their adornment. And God brought to a conclusion upon the sixth day the works that He had made; and God rested upon the seventh day from all His works.’ This is an account of the things formerly created, as also it is a prophecy of what is to come. For the day of the Lord is as a thousand years; and in six days created things were completed: it is evident, therefore, that they will come to an end at the sixth thousand year.”21

This is though different to the day-age interpretation that some old-earth creationists hold from the passage in Peter. Similarly, Theophilus, the 2nd-century Bishop of Antioch (AD 169–177) agreed that the earth was less than 6,000 years old (from his time of writing). He wrote that

“All the years from the creation of the world amount to a total of 5698 years, and the odd months and days … . For if even a chronological error has been committed by us, of, e.g., 50 or 100, or even 200 years, yet not of thousands and tens of thousands, as Plato and Apollonius and other mendacious authors have hitherto written. And perhaps our knowledge of the whole number of the years is not quite accurate, because the odd months and days are not set down in the sacred books.”22

We find also in the fragments of Hippolytus of Rome a belief that the Creation Week occurred in approximately 5500 BC.

“‘For as the times are noted from the foundation of the world, and reckoned from Adam, they set clearly before us the matter with which our inquiry deals. For the first appearance of our Lord in the flesh took place in Bethlehem, under Augustus, in the year 5500; and He suffered in the thirty-third year. And 6,000 years must needs be accomplished, in order that the Sabbath may come, the rest, the holy day ‘on which God rested from all His works. ‘For the Sabbath is the type and emblem of the future kingdom of the saints, when they “shall reign with Christ”, when He comes from heaven, as John says in his Apocalypse: for “a day with the Lord is as a thousand years.” Since, then, in six days God made all things, it follows that 6,000 years must be fulfilled.’”23

Part of Hippolytus’ justification was concerned with the size and adornment of the ark of Moses placed in the Tabernacle, which was covered in gold inside and out and measured in height, width and breadth, a total 5.5 cubits. Hippolytus believed that this distance signified the time of Christ’s coming, and the ark itself “constituted types and emblems of spiritual mysteries” that signified Christ and his coming. From this Hippolytus calculated that 500 years remained until Christ returned and would thus bring in the final Sabbath rest. “From the birth of Christ, then, we must reckon the 500 years that remain to make up the 6,000, and thus the end shall be.”24 Julius Africanus in the third century also held that the earth was around 5,500 years old, commenting “The period, then, to the advent of the Lord from Adam and the creation is 5,531 years.”25

However, we may note that Christ did not return in AD 500 as this millennial scheme suggested. This failure though did not seem to cause a great problem for Christians because of acceptance of the Masoretic Text (MT) and rejection of the LXX timeframe before AD 500.

The Septuagint, Masoretic Text and the age of the earth

Most of the Church Fathers of the first three centuries relied upon the LXX to determine the age of the earth and the Second Advent.26 Initially Christians believed that Christ would return sometime around AD 500. However, later acceptance of the MT, with its shorter timeframe for creation of around 4000 BC, extended the second coming to AD 2000.27 It is possible though that both the MT and the LXX differ somewhat from the Old Testament that was available in the time of Ezra, and the version that Jesus and the Apostles may have had access to. The Samaritan Text differs in fact from both the MT and LXX.

So, the gradual acceptance of the Hebrew MT by Christians, from which Bishop Ussher derived a date for the age of the earth of 4004 BC, gave fresh ‘legs’ to millennial thinking among Christians in more recent times, with Christ expected to return sometime around AD 2000. This transition from the LXX to the MT began as early as the 3rd century AD with Origen. His desire was to come to terms with the differences between the LXX and the MT and so he produced a six-fold interlinear version known as the Hexapla to aid his study. However, it was Jerome in the late fourth century who really brought the MT into the centre of Latin Christendom. Jerome had been tasked by the Pope Damasus I in AD 382 to produce a modern version in Latin, and instead of relying upon the older versions available in the Roman world that were translated from the LXX (the Vetus Latina), he largely took the MT as the basis for his new translation of the Old Testament, although many, including Augustine, thought this unwise. Augustine maintained that the LXX was the more reliable version, although he found the many different Latin versions translated from the LXX to be frustrating.28 Jerome’s Vulgate version, however, became the accepted Old Testament in the Roman world for many centuries, and the older Latin versions that were based upon the LXX fell into disuse. And following the Reformation the translators of the King James Bible turned to the MT for the basis of their own work, and this forms the backbone for most modern versions. The Greek Orthodox Church incidentally continues to favour the LXX.

I don’t have space here to go into detail about which is the more accurate version, but it is worth mentioning that some Old Testament quotes from the New Testament are closer to the LXX and speak more strongly of the Messiah than does the MT, i.e. Hebrew 1:6 quotes a verse from Deuteronomy 32:43 that reads: “And again, when God brings his firstborn into the world, he says, Let all God’s angels worship him” but this is missing from the MT.29 So we shouldn’t automatically assume the MT is the more accurate version. Whitcomb and Morris, however, believed at least some of the dates in the LXX were false, but were seemingly open to a slightly longer timeframe for creation, holding that several thousand years may have passed between the Flood and Abraham.30 The differences between the MT and LXX offer a legitimate area for creationist research, although beyond the scope of this paper.

But despite Jerome’s new translation, Augustine continued to favour the LXX, holding that the earth was less than 6,000 years old, but it is less clear that he linked it to the second coming. He wrote:

“Let us, then, omit the conjectures of men who know not what they say, when they speak of the nature and origin of the human race. For some hold the same opinion regarding men that they hold regarding the world itself, that they have always been … . They are deceived, too, by those highly mendacious documents, which profess to give the history of many thousand years, though, reckoning by the sacred writings, we find that not 6000 years have yet passed. (The City of God, XII:10).”31

It is true that Augustine’s beliefs were different in places from those of modern creationists. Like Philo, Augustine believed for a long time that God created everything at once and that the six days of creation should be considered symbolic. His position though was based upon a Latin translation of the Apocrypha verse (Sirach 18:1) that failed to translate the Greek adequately. This reads in the Latin translation as “He that liveth for ever created all things together [or simultaneously]” (or qui vivit in aeternum creavit omnia simul),32 and this appears to have coloured his belief. However, in the earlier Greek the passage reads as panta koinee, which can be rendered as ‘all things in fellowship’, implying that God created the world as an integrated whole.33

However, in later writing Augustine seems to have moved towards acceptance of temporal creation days, although with remaining concern that the creation account mentions the passage of morning and evening on Days 1 to 3 prior to the formation of the sun and moon on Day 4. Augustine speculated in The City of God about whether there was some material light or whether the light during those three days was that of the heavenly City of God shining upon the newly formed Earth. However, he urges us to believe it whether we understand it or not. He writes:

“But simultaneously with time the world was made, if in the world’s creation change and motion were created, as seems evident from the order of the first six or seven days. For in these days the morning and evening are counted, until, on the sixth day, all things which God then made were finished, and on the seventh the rest of God was mysteriously and sublimely signalized. What kind of days these were it is extremely difficult, or perhaps impossible for us to conceive … what kind of light that was, and by what periodic movement it made evening and morning, is beyond the reach of our senses; neither can we understand how it was, and yet must unhesitatingly believe it.”34

Augustine’s difficulty seems to be that of reconciling creation by an eternal God, who dwells outside of time, with the creation of matter in a temporal reality. But as with the origin of this world, Augustine is critical of those who propose long ages for the creation of man, believing instead that mankind was created in time in the recent past.

“As to those who are always asking why man was not created during these countless ages of the infinitely extended past, and came into being so lately that, according to Scripture, less than 6,000 years have elapsed since He began to be. … For, though Himself eternal, and without beginning, yet He caused time to have a beginning; and man, whom He had not previously made He made in time, not from a new and sudden resolution, but by His unchangeable and eternal design.”35

It might be pointed out in passing also that a 24-hour day is dependent on the spin of the earth on its own axis independent of the sun, and even at the poles today we may note that a 24-hour day does not require the sun to set. But for Augustine the age of the earth was determined through the sacred writings, in a literal manner, in opposition to the pagan texts that existed at that time. Many of the pagan nations prior to Christ held a belief that history extended back for hundreds of thousands of years, and many of the early Christians leaders, such as Augustine and Tertullian, wrote openly against the pagan philosophy. For the early Christians it was held that 6,000 years had not passed by that time since the foundation of the world.

Conclusion

It would seem then that there was a widely held belief in a recent creation during the few centuries following the events of Christ’s life on Earth. This was linked to a millennial scheme where the six days of creation prefigured 6,000 years of Earth history, followed be a millennial seventh ‘day’ of rest. Such millennial schemes are found in the writing of Irenaeus, Justin Martyr, Hippolytus, Theophilus, and Basil. By the fourth century, Basil continued to uphold a belief in a literal creation as opposed to a purely figurative one, and this literal–symbolic interpretation was present in the writing of Augustine also. Augustine believed in both a recent creation and a global Flood, but saw symbolism relating to the person and work of Christ throughout the Old Testament. Augustine seems to have believed that God made everything at once in the recent past, but he did not believe in millions of years of change. Later (in The City of God), this belief was seemingly modified as he tried to come to terms with six literal days, but he continued to think that the light of days 1 to 3 might have been spiritual light from the heavenly city as opposed to physical light. Finally, we may observe that modern young-earth creationism is recognizably similar to the teachings of the Church Fathers, even if differing in some places, and is not a radical departure from Christian tradition.

References

- In this paper I have mainly made use of Philip Schaff’s Anti-Nicene Fathers (10 vols. first published 1885), and Nicene and Post Nicene Fathers (Series I and II, 1886–1890), available online at www.ccel.org. Return to text.

- Alexander, D., Evolution or Creation: Do We Need to Choose? Monarch Books, Oxford, pp. 351–353, 2009. Return to text.

- Forster, R. and Marston, P., Reason, Science and Faith, Monarch Books, Oxford, 1999, pp. 200–201. Return to text.

- Forster and Marston, ref. 3, pp. 237, 241. Return to text.

- And I personally have a great deal of respect for him as I attended an Ichthus linked church for many years and have heard him speak a number of times. I have also met a number of other young earth creationists within his group of churches. Return to text.

- Forster and Marston, ref. 3, pp. 203–204, referring to Origen, Homily I and First Principles, IV:3. Return to text.

- Basil, Hexaemeron Homily IX:1. Return to text.

- Basil, Hexaemeron Homily II:8. Return to text.

- Biblical references here are from the text notes of Schaff’s Nicene and Post Nicene Fathers. ‘Octave’, for instance, appears in the Douay Rheims, American Edition, 1899 (a Catholic translation from the Vulgate). One may also consider the prophetic significance of the preparation of priests and the eighth day of the Feast of Tabernacles (Lev. 9:1, 23:33–44). Return to text.

- Basil, Hexaemeron Homily IX:1, III:3, and II:8. Basil wonders why the Christian belief in several heavens should be seen as foolish when the Greek are willing to propose “infinite heavens and worlds”. Return to text.

- Basil, Hexaemeron Homily II:8, “in reality a day is the time that the heavens starting from one point take to return there. Thus, every time that, in the revolution of the sun, evening and morning occupy the world”, and in Homily IX:2, “We see mud alone produce eels; they do not proceed from an egg, nor in any other manner; it is the earth alone which gives them birth. Let the earth produce a living creature.” Return to text.

- Augustine, De Genesi ad Litteram (The Literal Meaning of Genesis) 3.14.23 & 4.33.51, translated and annotated by Taylor, J.H., Newman Press, New York,1982. Return to text.

- Forster and Marston, ref. 3, pp.200–201. They merely quote, without a page reference, from Jaki, S., Genesis 1 through the Ages, 2nd edn, Scottish Academic, 1998. The reference to air and thunder in Basil has been sourced from Hexaemeron Homily III:4; the reference to Heaven and smoke is from Homily I:8, but Basil comments further that “He created a subtle substance, without solidity or density, from which to form the heavens.” Return to text.

- Basil, Hexaemeron Homily III:7. Return to text.

- Augustine, The City of God, Book XV, ch. 27; entitled ‘The Ark and the Deluge, and that We Cannot Agree with Those Who Receive the Bare History, But Reject the Allegorical Interpretation, Nor with Those Who Maintain the Figurative and Not the Historical Meaning.’ Return to text.

- McGrath, A.E., Christian Theology: An Introduction, 3rd ed., Blackwell, pp. 171–178, 2002. Return to text.

- Irenaeus, Against Heresies 5:XXIIII:4, “And these things are borne witness to in writing by Papias, the hearer of John, and a companion of Polycarp, in his fourth book; for there were five books compiled (συντεταγμένα) by him.” And in Against Heresies 5.XXX:4, “then the Lord will come from heaven in the clouds, in the glory of the Father … bringing in for the righteous the times of the kingdom, that is, the rest, the hallowed seventh day”. Also see Papias, Fragments ch. IX (sourced via Anastasius Sinaitia), which reads, “Taking occasion from Papias of Hierapolis, the illustrious, a disciple of the apostle who leaned on the bosom of Christ, and Clemens, and Pantænus the priest of [the Church] of the Alexandrians, and the wise Ammonius, the ancient and first expositors, who agreed with each other, who understood the work of the six days as referring to Christ and the whole Church.” Return to text.

- Epistle of Barnabas, XV:4; The Catholic Encyclopedia, entry on ‘The Apostolic Fathers’, 1917, “even if he [Barnabas] be not the Apostle and companion of St. Paul, is held by many to have written during the last decade of the first century [ad 96–98], and may have come under direct Apostolic influence, though his Epistle does not clearly suggest it.” Return to text.

- Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho, pp. 80–81. Return to text.

- Forster and Marston, ref. 3, p. 201. Return to text.

- Irenaeus, Against Heresies 5:XXXVIII:3. Return to text.

- Theophilus to Autocylus 3:28–29. Return to text.

- Hippolytus, Fragments—Hexaemeron, On Daniel II:4. Return to text.

- Hippolytus, On Daniel II:5–6. Return to text.

- Julius Africanus, Chronography 18:4. Return to text.

- The LXX was written over several centuries prior to Christ by Alexandrian scribes, and gave an age of the earth around 5500 BC. Return to text.

- The MT is in fact derived from a standardized Hebrew version laid down by the Jewish Scribes and Pharisees around the late first century AD through the Council of Jamnia. This was for the reason of bolstering Jewish adherence, and to distance Judaism from Christianity. Jewish Christians had fled Jerusalem in AD 68 for Pella (following Jesus’ prophecy relating to the sign of the abomination that causes desolation; see: Matt 24:16) and which increased distrust between Christians and Jews. Return to text.

- Augustine, On Christian Doctrine, 2:16. Return to text.

- LXX Deut 32:43, “Rejoice, ye heavens, with him, and let all the angels of God worship him; rejoice ye Gentiles, with his people, and let all the sons of God strengthen themselves in him; for he will avenge the blood of his sons, and he will render vengeance, and recompense justice to his enemies, and will reward them that hate him; and the Lord shall purge the land of his people.” MT Deut. 32:43 has “Rejoice, O nations, with his people, for he will avenge the blood of his servants; he will take vengeance on his enemies and make atonement for his land and people.” Return to text.

- Whitcomb, J.C. and Morris, H., The Genesis Flood, Baker Books, Grand Rapids, MI, pp. 474–484, 1961. Return to text.

- Augustine, The City of God, Book XII, ch. 10, ‘Of the falseness of the history which allots many thousand years to the world’s past.’ Return to text.

- From Douay Rheims, 1899 (Vulgate). Although Jerome used the MT to translate the main Hebrew text, he referred to the LXX and Vetus Latina for parts of the Apocrypha. Return to text.

- See for instance Zuiddam, B., Augustine: young earth creationist, J. Creation 24(1):5–6, 2010. (The full text of an interview of which a summary in Dutch appeared in Reformatorisch Dagblad, 15 April 2009). See also Galling, P. and Mortenson, T., Augustine on the Days of Creation: A look at an alleged old-earth ally, Answers in Genesis, 18 January 2012. Return to text.

- Augustine, The City of God, Book XI:6 & 7, “That the World and Time Had Both One Beginning, and the One Did Not Anticipate the Other” and “Of the Nature of the First Days, Which are Said to Have Had Morning and Evening, Before There Was a Sun”. Terry Mortenson writing in The Great Turning Point, Master Books, Green Forest, AR, pp. 40–41, 2004, suggests a movement towards a more literal reading of the creation account in Augustine’s writing in later life. Return to text.

- Augustine, The City of God, Book XII: 12 & 14, “How These Persons are to Be Answered, Who Find Fault with the Creation of Man on the Score of Its Recent Date” and “Of the Creation of the Human Race in Time, and How This Was Effected Without Any New Design or Change of Purpose on God’s Part”. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.